|

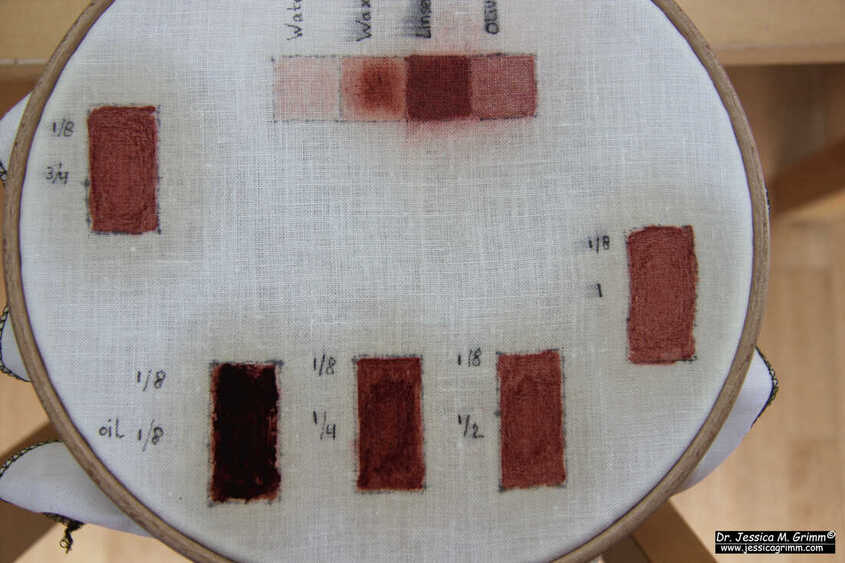

When you start to analyse medieval goldwork in detail, you'll find all sorts of things that are not practised in modern goldwork embroidery. One of these is the use of madder (Rubia tinctoria), a red pigment to colour the embroidery linen in those areas that get covered with goldthreads. How widespread the use of this pigment was is difficult to say. Its use can only be observed when an embroidery is damaged. However, as it is not present on each damaged embroidery the use of madder was not a necessity. As far as I know, the madder was first chemically identified on pieces from the Schnütgen Museum. The reason given by Sporbeck for its use is that the inferior quality of the membrane gold used in Germany needed this reddish base to enhance its shininess. She falsely concludes that the use of madder is probably unique to embroideries made in Cologne. However, the madder can be found under Dutch embroideries also. It was probably simply used to prevent the white linen to shine through the golden backgrounds stitched with geometric diaper patterns. Especially when patterns with larger intervals between the individual couching stitches were used, the goldthreads may gape and reveal the white linen. The colour red enhances the shine of the gold and tricks our eyes into believing that the background is whole and smooth. But how was the madder applied?

As the madder is only applied on those areas of the embroidery linen that later get covered with goldthread, the medieval embroiderers did not simply use madder dyed embroidery linen. I think this has to do with the silk embroidery. The red background colour might interfere with the very light silk used in the faces. In order to be able to only use the red colour in certain areas the person who drew or printed the design onto the embroidery linen must have used a paint-like substance. What binding agent was used to turn madder powder into paint?

In the above FlossTube with the Acipictrix video, you'll see me experimenting with different binding agents. Whilst madder powder is hydrophobe and does not dissolve well in water, you can actually stain your embroidery linen just enough to get rid of the stark white. The binding agent that has worked best so far is linseed oil. You'll need 1/8 teaspoon of madder powder and 1 teaspoon of linseed oil to get a paint-like substance that adheres well to the linen without excess madder powder sitting loosely on top of the fabric. This shows that the pigment is very economical in its use. Both madder and linseed were common, inexpensive and local products.

The one thing that bugs me about the use of oil as the binding agent is that it seeps into the embroidery linen. This was apparently a common problem for painters too. In the reconstruction of the Nachtwacht by Rembrandt, the modern painters had the same problem. The canvas kept sucking up the linseed oil paints. They remedy this problem the same way the people in Rembrandt's workshop would have done: by drenching the canvas in more linseed oil. However, this would not have been necessary for the medieval goldwork embroideries. They were completely covered with embroidery and the 'halos' of seeped oil would simply not be visible.

When I had found my preferred recipe for the madder paint and applied it to my embroidery linen, I was amazed that you can easily stitch on it. It does not feel oily and it does not seem to interfere with either your silken couching thread or with the goldthreads. I have no idea how long the 'halo' stays visible. It is difficult to see if there is a halo on the damaged goldwork embroideries (explore: ABM t2007, ABM t2107a, ABM t2121b, ABM t2147, ABM t2149, ABM t2158 & OKM t156a). However, in the picture above, you do see some staining on the back of ABM t2107f. This might be the result of the oil used as a binding agent.

Just a word of caution: If you would like to experiment with making your own madder paint with linseed oil, be careful. Linseed oil generates heat when it dries. Under the right circumstances, it can combust and cause a fire. Always let fabrics drenched in linseed oil dry completely before you throw them in the bin. Literature Leeflang, M., Schooten, K. van (Eds.), 2015. Middeleeuwse Borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden. WBOOKS, Zwolle. Sporbeck, G., 2001. Die liturgischen Gewänder 11. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Sammlungen des Museum Schnütgen 4. Museum Schnütgen, Köln.

11 Comments

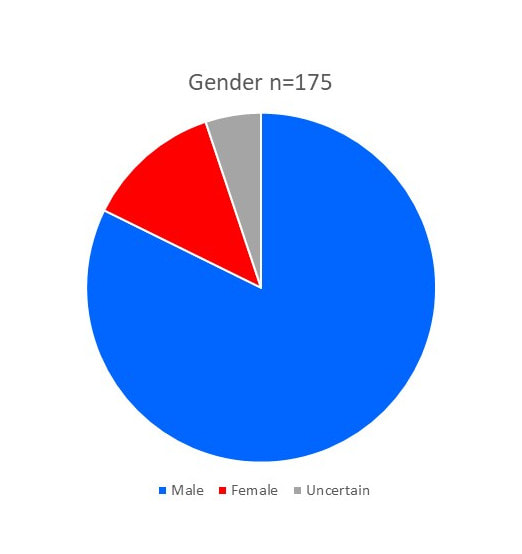

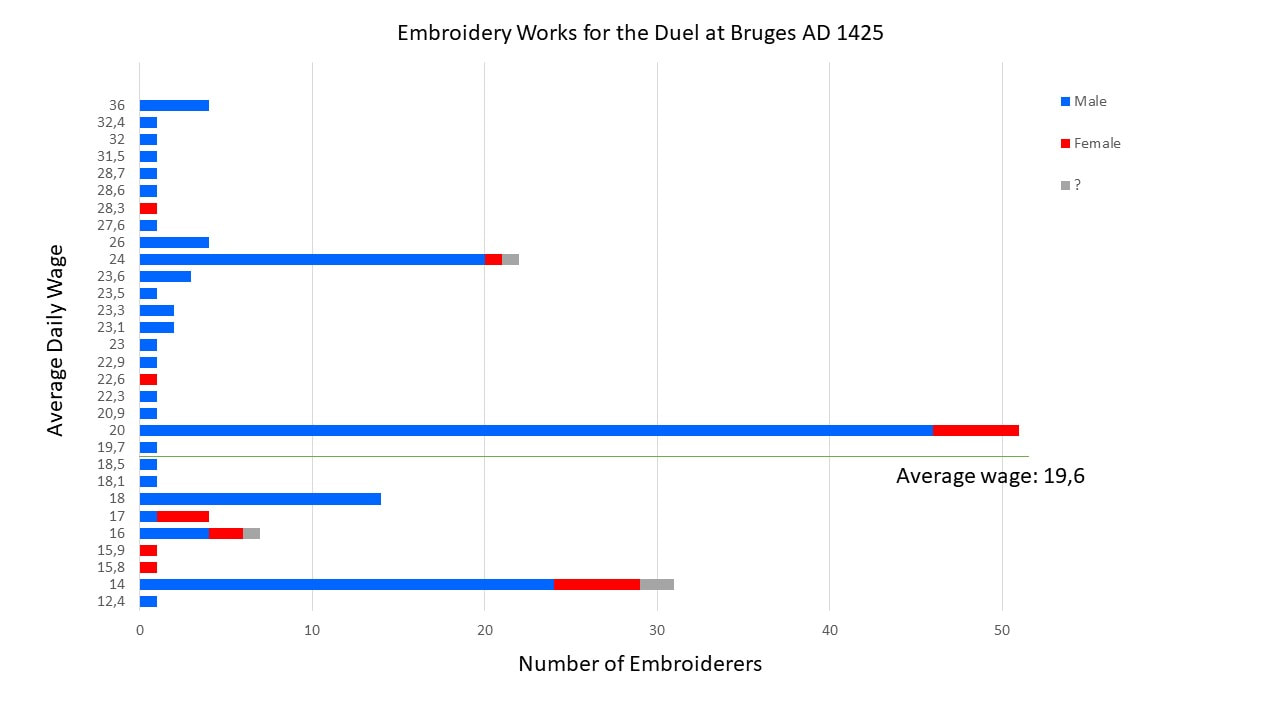

Seldom do we have a chance to meet the people who created the medieval embroideries. Especially written sources containing the names of female embroiderers are rare as hen's teeth. Imagine my delight when I found an older Belgian publication that contains precisely that! It is a list of 175 (!) people who were drawn in from all over the place to help embroider equipment, clothing and tents for a duel between Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and Humphrey Duke of Gloucester. The original documents preserved do not only tell us something about the embroiderers and other craftspeople involved, we also have a list of the embroidered items. Let's explore! Why did these two men think it a good idea to fight till death? It was about a woman: Jacqueline Countess of Hainaut. She interfered, with her second husband Humphrey, in the power politics of Philip the Good by trying to claim her rights in Hainaut. In essence, it was a family feud as most of these people were closely related to each other. In order to have the most splendid kit to try to kill Humphrey, Philip ordered his man Andre de Thoulongeon to ride to Paris in haste to collect master craftsmen in the art of weaponry, painting and embroidery. Andre contacted Thomassin de Froidmont, Philip's weaponry master, Thierry du Chastel, who later surfaces in the historical sources as Philip's head embroiderer and the painter Hans de Constance (his name suggests he came from Konstanz in Southern Germany). Painter Hans came to Bruges and worked for 70 days on the embroidery designs. Simon de Brilles, an embroiderer of Philip, was asked to take care of the masters that came from Paris and to direct the embroiderers that worked on repairing the embroidery on the weapons and Philip's tent. The first embroiderers arrived at Bruges on the 26th of March 1425. They worked in the ducal palace. Over the next weeks, more and more embroiderers arrived. They came from Bruges, Ghent, Lille, Brussels, Mechlin, Antwerp, Tournai and many other places. All in all, 175 people of which 22 were certainly women (I wasn't sure about 9 names if they were male or female). This underlines the general impression I have so far gotten from the historical documents that significantly more men worked as professional embroiderers than did women. Some people stayed the whole 70 days and others came for only a couple of days. They finally completed the task on the 21st of June. What did 175 embroiderers produce between the 26th of March and the 21st of June 1425? They made seven horse trappers made of velvet and embroidered with the coat of arms of Philip or his counties, his motto and the cross of St Andrew. As far as I know, the only surviving medieval embroidered horse trapper is held at Musee Cluny in Paris (Cl. 20367 a-g). They also made tabards, those heavily decorated tunics that were worn over chainmail or harness. Furthermore, banners and a tent needed to be decorated with embroidery. The Belgian authors think this not to be very much ... Why then did some embroiderers have to work through the night to get it finished in time?! In the end, it was all for nought. Philips and Humphrey decided that trying to kill each other wasn't the best way to solve the conflict. Diplomacy did. On the 23rd of Mai 1425, the duel was called off. Interestingly, the embroidery works continued until the 21st of June. The, no doubt, splendid embroideries were transported to Lille on the 9th of September and kept there for safekeeping. Maybe they were used for the tournament in which Philip the Good and John of Lancaster both appeared in 1427. There is a written source that confirms that the tent made for the duel could still be admired in Lille in 1460. Unfortunately, none of the embroideries seems to have survived till the present day. The list in which the embroiderers are listed shows some interesting details. Foremost, we learn how much each of them was paid. Some got the same payment for each day they worked, others got different wages on different days. Was this because costs spiralled out of control? Or were different tasks paid differently? I tend to think it is the latter. You were presumably assigned to a certain task and when that task was completed you got assigned the next one when you decided to stay on. Those who practice goldwork embroidery probably know that some techniques and designs require more skill than others. Related to this is the payment of the female embroiderers. The Belgian authors state that the work of women was rewarded less. This conclusion is probably cut too short. Lievin van Bustail, Lyzebette Peytins and Yoncie Hevre all earn quite a bit above the average wage of 19,6 gr. It is true, however, that the top earners are men and that 14 of the 22 women earned wages below the average. Four women came with their husbands: Ernoul and Marguerite de Wesemale both became the same wage of 20 gr., the same is true for Alard and Katherine du Dam. Jaquet d'Utrecht earns 20 gr, his wife (not named) earns 16 gr. and his boy (not named) 14 gr. Pietre de Hond only earns 18 gr. and his wife (not named) earns even less at 14 gr. Young boys either earned 14 gr. or 11 gr. This seems only fair as these were probably still training with their masters (maybe their fathers?) and were thus not that skilled. I am therefore thinking that embroiderers were primarily paid according to skill and not according to their gender. For those of you who like to play with the raw data below is the Excel list for you to download. If you can help sex any of the names now a '?' or if you see a mistake, please let me know!

Literature

Duverger, J., Versyp, J., 1955. Schilders en borduurwerkers aan de arbeid voor een vorstenduel te Brugge in 1425. Artes Textiles II, 3–17. About 15 years ago, I attended a lecture by Ms H.E.M. Cool. She is the author of the book 'Eating and drinking in Roman Britain'. One of my favourite books on archaeology. But that lecture was nothing I thought it would be. Instead of an overview on small finds related to food and drink in Roman Britain, we got a highly controversial lecture on the stark domination of female archaeologists in small finds. Female domination sounds good, doesn't it? Wrong. It is bad. You see, many female archaeologists end up as a finds specialist. You are in the office instead of in the field and this career path can be combined with raising children, supporting a husband in his career or simply with having a catastrophic period each month. So far, so good. However, we do not live in a perfect world. When a workforce is dominated by women it gets taken less seriously (think elementary school teacher, nurse, etc.). Payment goes down. Fewer men enter as the overall perspective of making promotion diminishes. As a result, the workforce becomes even more 'girly'. Ms Cool spoke to a mainly female audience. Ms Cool was very angry; that sacred kind of angry. Not because she wanted to drag some younger female archaeologists through the mud, but because she cared deeply. Nevertheless, no doubt, some thought of her as a traitor. On me, she made a lasting impression. What does this have to do with medieval embroidery? Read on! Research into historical textiles is dominated by women too. This wasn't always the case. We had Joseph Braun and Louis de Farcy at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century and Donald King who died in 1998, to name a few. But when more people got an academic education, more women ended up in textile research and fewer men entered the discipline. I don't want to speculate about why so many women ended up in textile research. The 'why' doesn't matter. What matters is that the discipline became female-dominated. And with it, it lost its serious character. Some people, who started out as brilliant researchers on medieval embroidery, switched to studying paintings instead (Saskia de Bodt). Better career opportunities there, no doubt. Academics involved in the recent high-profile research project on the Imperial Vestments were told that 'university isn't a Kindergarten' when they tried to recreate stitch plans. So, what do we do when a discipline such as embroidery research is not being percieved as serious? We make sure that we adhere to academic standards and that we are professional. And here comes the controversy of my plea. If we want to be seen as serious researchers in a mature discipline, we cannot quote: comments from Facebook groups on historical embroidery, generic introductions in embroidery project books, blogs by hobbyists who do not state their references, etc. However right these sources might be. We usually have no means of verifying them. If you cannot verify a source it does not pass academic standards and it should thus not be used. It is perfectly fine to use any of these sources as your starting point for more research. And you should credit them accordingly. Bluntly copying them, even with a proper reference, should be avoided at all times. Does this mean that only academics have a monopoly on proper research? No. Anyone who states his or her sources which then can be verified produces proper research and is thus a totally valid source. Here is another story from the days when I was still an archaeozoologist. When I publicly defended my doctoral thesis, one of my examiners was not an archaeologist, nor a biologist or a veterinarian, instead, he was a historian. And he hated my thesis. Analysing thousands of medieval animal bones from older sub-standard archaeological excavations and then translating the results into a 500-year history of husbandry strategies and trading with animal products does not produce many definitives or truths. Instead, you need to eat humble pie and use the words 'possible', 'probably' and 'might' a lot. Back then, older historians were not used to this. When you work with written sources they surely must be true! What does this have to do with medieval embroidery? Read on! Those who have taken my Medieval Goldwork Course know that research is never finished. Got new evidence? The narrative changes. A 'possible' becomes a 'probable' or the idea is dropped altogether. This resulted in an updated course for the second run and then again an updated course for the third run. And no doubt, things being tested out by the students of the third run will influence any future runs of the course. I am still learning every day about medieval embroidery practice. And I need my students very much to point me to things I haven't thought of myself. But. And this is an important but! All their ideas need to hold up to academic scrutiny. They need to be verified before they can become part of my academic research.

Going to university and being trained to become an academic means that you are being equipped with a set of skills. You could view this as a toolkit. Learning these skills takes time and professionals who teach them to you. Just like with any other occupation people embark on learning. In the case of becoming an academic, learning to verify sources and to validate sources is probably the most important skill they'll teach you. People seem not to be born with this skill. Some people say that we live in a post-truth era. As academics and other experts sometimes err there is no truth and all opinions are equally valid. For instance, the opinion of your barber on vaccination is as valid as your family doctor's opinion on vaccination. Really? Personally, I do not want to live that way. It has prevented humanity so far from taking decisive action to avert climate change and to properly react to the pandemic (a small cog in the machine called climate change). It also massively threatens our democracies. Alternative facts, anyone? It is clear to me that some who read this will see me as an arrogant academic who thinks she is above 'normal embroiderers'. Nothing could be further from the truth. I've set up the Medieval Embroidery Study Group for embroiderers who want to continue their studies in medieval embroidery. Think of it this way: academics theorising about embroidery without ever holding a needle are as daft as hobby researchers who cannot support their claims with proper references. There are now so many textile societies embroiderers can join regardless of their educational background. If you are interested in archaeological recreations try EXARC, if you like medieval textiles join MEDATS and if you like dress history you might want to check out the ADH. Here you have access to cutting edge new research and you are very welcome to contribute your own thoughts (again: they will need to hold up to academic scrutiny). Contrary to Facebook groups, you need to pay a small yearly fee to join these societies. But remember: Facebook's free is costing society an arm and a leg! This is going to be an exciting year medieval-embroidery-wise. I have quite a few special things lined up for you all. Most importantly, the third run of my Medieval Goldwork Course is now fully booked. From the introductions, I gleaned that it is quite an international group with many interesting backgrounds that will really add to the study of medieval goldwork embroidery. As I am now quite confident that I have my supply lines secured, I've decided to work with a waiting list. My plan is to run the course for the fourth time in the autumn. You can express your interest by dropping me a line. I'll decide at the end of Mai if all stars line up correctly. If they do, I'll notify the first 15 people on my list. You'll have a couple of days to decide if you want to take the course. If you don't, I'll notify number 16 on the list, etc. But that's not all I have in store for you this year! Read on ... During the holidays, I've cleaned out my webshop. Shipping has become very expensive due to reduced air traffic. This means that I have ditched most of the physical goods. But fear not! There's plenty left. And, I have even added some gorgeous Italian linen (Sotema). It is of the higher-count-kind. As the holes are really distinct, it is actually easier on the eyes than the more commonly used lower-count varieties from Zweigart. Apart from teaching my online course, I will also be teaching a weekend-long medieval goldwork embroidery class at the Glentleiten open-air museum. This class will be taught in German and is specifically geared towards embroiderers from Germany, Austria and Switzerland. You will make a small sampler with three common medieval goldwork elements. You will also learn to dress a traditional slate frame (included with the course fee). The course will probably take place on the 16th and 17th of July. Once all details have been cleared with the museum, the course will be visible under the 'learn tab' at the top of my website. As a weekend is far too short to finish the complete sampler, this is going to be a hybrid course with how-to videos you can watch at home after the actual event. As making these takes quite some time, I don't have a finished class sample to show quite yet. In the coming weeks, I will review this lovely book, write a blog post on a long list of named embroiderers from 1425 (it includes some women!) and I will introduce you to another antique bedouin dress I bought last year. Plenty to look forward to!

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed