|

The 14th century Grandson Antependium. It is a pretty mix of embroidery techniques, styles, languages and geographical areas. Let's explore! The Grandson antependium is housed at the Historisches Museum in Bern, Switzerland and catalogued under Nr. 18. It is 244 cm wide and 88 cm high and consists of three separate parts. The knight kneeling to the left of the central figure of the Virgin and Child is the donor of the piece. His coat of arms identifies him as Othon de Grandson (c. 1238-1328). Although born near Lausanne in Switzerland, he became a close friend of King Edward I of England. Othon de Grandson travelled widely throughout Europe and the Mediterranean area when he joined the 9th Crusade. Othon accumulated great wealth and donated it to various religious institutions in both England and Switzerland. This particular antependium was donated to the Cathedral of Lausanne where Othon is entombed. With the amount of gold used for the embroidery, it must have been a very expensive piece. The central part of the antependium shows the enthroned Virgin and Child with two vases with foliage and two angels with censers on either side. The design has a Byzantine flavour which is emphasised by the Greek embroidered inscription for the name of Christ. But that's not the only language used. Mary is addressed in Latin and the two angels are addressed in ancient French. The design isn't purely Byzantine either: the censers are distinctively Western European. Byzantine embroideries with embroidered donor figures are not known in this era either. Where was this piece made? And for whom originally? Most scholars now agree that the central part of the embroidery was likely made in Cyprus. The island is conveniently placed en route to the Holy Land and also served as a retreat base when things went wrong during the crusade. Cyprus belonged to the Byzantine Empire with its Eastern Orthodox version of Christianity. At the same time, it had ample visitors from the West. Was the central composition mostly finished when Othon saw it at a Cypriot embroidery workshop? Where the texts added on his request? The knightly figure and the coats of arms certainly were. And then we have the two separate side panels. Very different from the central panel. Style, embroidery technique and materials used differ from the central panel. And their design is non-religious. The side panels are thought to have been embroidered in England as they sport underside couching. Is this a rare remnant of non-religious opus anglicanum? Did Othon come across two embroidered soft furnishings in England that together with the panel he probably acquired in Cyprus would make up a fitting antependium for the high altar in his cathedral back home? As the embroidery is cut at the top, the two panels were not specifically intended for that high altar when they were made. I think we see a rare glimpse of opus anglicanum 'for the noble home' preserved in this extraordinary antependium. What do you think? Literature

Martiniani-Reber, Marielle (2007): An exceptional piece of embroidery held in Switzerland: the Grandson Antependium. In Matteo Campagnolo, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (Eds.): From Aphrodite to Melusine: Reflections on the Archaeology and the History of Cyprus. Geneva: La pomme d'Or, pp. 85–89. Stammler, Jakob (1895): Der Paramentenschatz im historischen Museum zu Bern in Wort und Bild. Bern: Buchdruckerei K.J. Wyss. Schuette, Marie; Müller-Christensen, Sigrid (1963): Das Stickereiwerk. Tübingen: Wasmmuth. Woodfin, Warren T. (2021): Underside couching in the Byzantine world. In Cahiers Balkaniques 48, pp. 47–64.

1 Comment

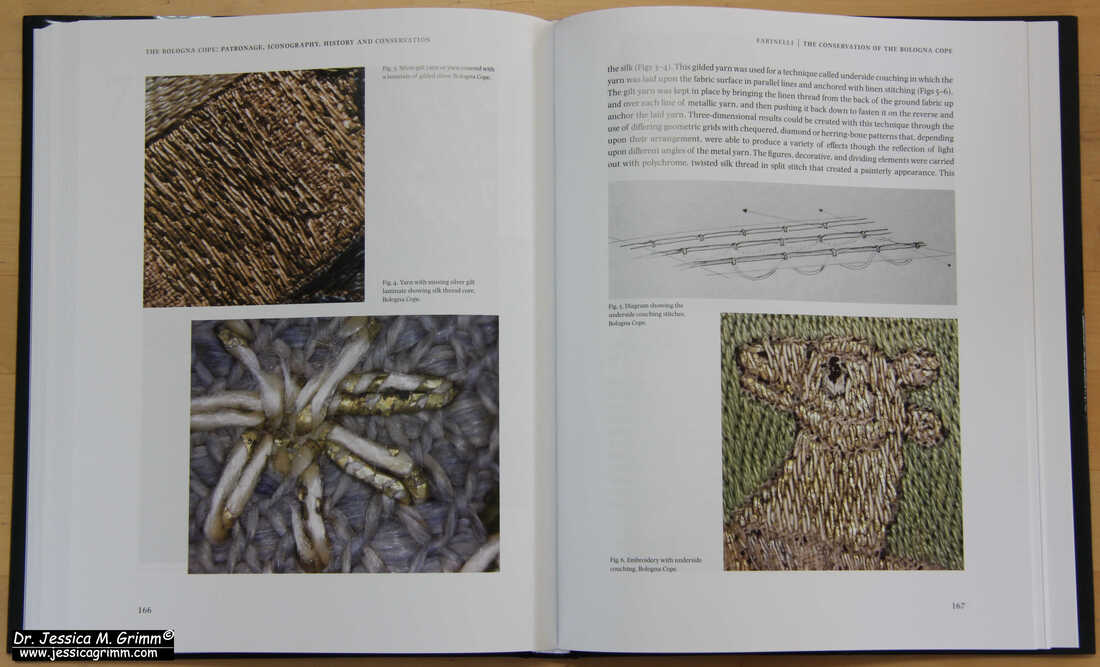

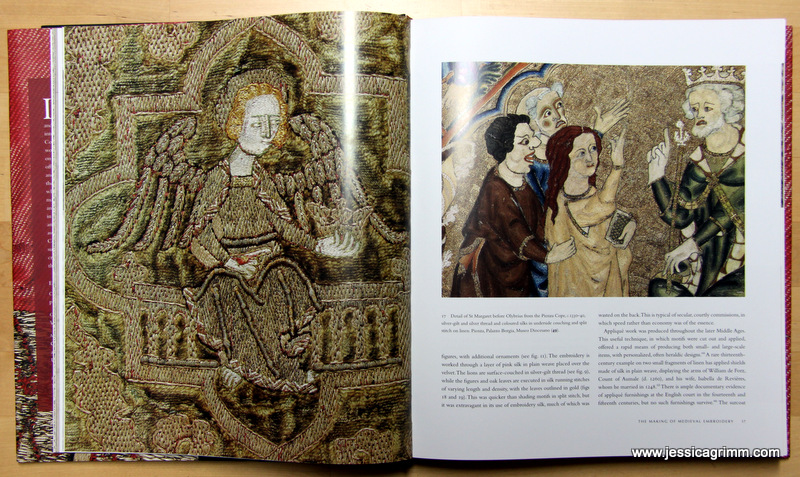

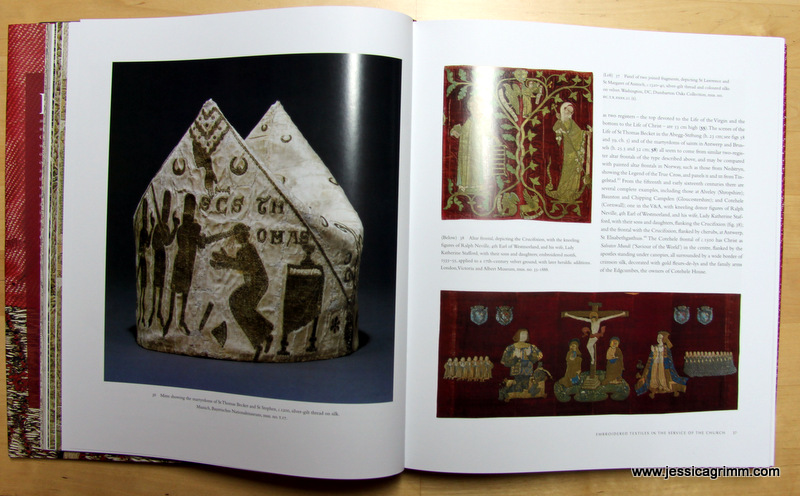

Today I am going to introduce a new book on Opus anglicanum to you. One of my students posted about it in the Medieval Embroidery Study Group. As the book is written in English, the language used by most people in the international embroidery scene, these books are too important to ignore. They have the potential to become gospel. At € 125 + shipping, the book isn't exactly a bargain. So, let's explore its contents together so that you can make an informed decision as to whether to buy it or not. The Bologna Cope: Patronage, iconography, history and conservation is edited by M.A. Michael and is the second volume in the series "Studies in English Medieval Embroidery". The book can be ordered through Brepols publishers. As the Bologna cope is held in an Italian museum, the book's chapters are mainly written by Italian scholars. But as the editor is from the UK, the book is published in English. Italy has many splendid medieval embroideries and a large body of literature about them. However, it is all published in Italian. Not a language most of us are fluent enough in. The book starts with a general introduction to the subject. Those of you who went to see the Opus anglicanum exhibition in the Victoria & Albert Museum a couple of years ago, probably remember the Bologna cope as it was displayed right at the entrance. This first chapter also briefly introduces us to a few other embroidered vestments held in Italy. Neither the iconography on these pieces nor their embroidery techniques are described. The pictures are mostly not detailed enough to fill in the blanks. The second chapter is by M.A. Michael himself and mainly deals with stylistic comparisons between the design of the cope and several other works of contemporary art. It does have a rather good overview of the historical sources containing references to the makers and dealers in Opus anglicanum. However, a lot remains unclear as the dealers can often not be confidently separated from the makers. If you want to know more about the makers of Opus anglicanum, this chapter is not going to add much. A large chapter is devoted to the iconography of the cope. It is illustrated with many pictures of the embroidery. However, as many of the scenes are quite large, the pictures are mostly not detailed enough to learn more about the embroidery. Only a hand full provide enough detail. The next two chapters will not be of interest to most embroiderers. One chapter deals with the possible references made to this cope in the inventories of the Friars Preachers in Bologna. And the other chapter deals with the publication and exhibition history of the cope. The 6th chapter sounds very promising: "Textiles and Embroidery in Italy between 1200 and 1300". Unfortunately, the majority is on the fabrics and not on the embroidery. And don't be fooled. We are not getting an overview of embroidered pieces made in Italy in the 13th-century. It only briefly explores the remaining textiles associated with Pope Benedict XI (donor of the Bologna cope) and his predecessor Boniface VIII. Are there no other 13th-century Italian embroideries? There are! They can be found in the Victoria & Albert Museum, in the Domschatz in Aachen, in the Keir Collection and in the Museo Episcopal Vic. As I don't read Italian very well, my research into Italian medieval embroidery is slow and far from complete. This chapter should have been an excellent opportunity to thoroughly introduce a non-Italian reading audience to the topic. But it is the last chapter that really has me fuming: "The conservation of the Bologna cope". This chapter should contain a section on the materials and techniques used to create the embroidery on the cope. It doesn't. We are only told that the embroidery is executed on two layers of linen. Count, please! The gold threads are made of silver gilt foil wrapped around a silken core. Composition of the metals? Spun directions? Colour of silken core? Thickness? Any details of the silken threads used for the split stitch embroidery? Length of stitches? The chapter does contain a few close-ups and a few macro images (no scale!). But that is all. What a missed opportunity.

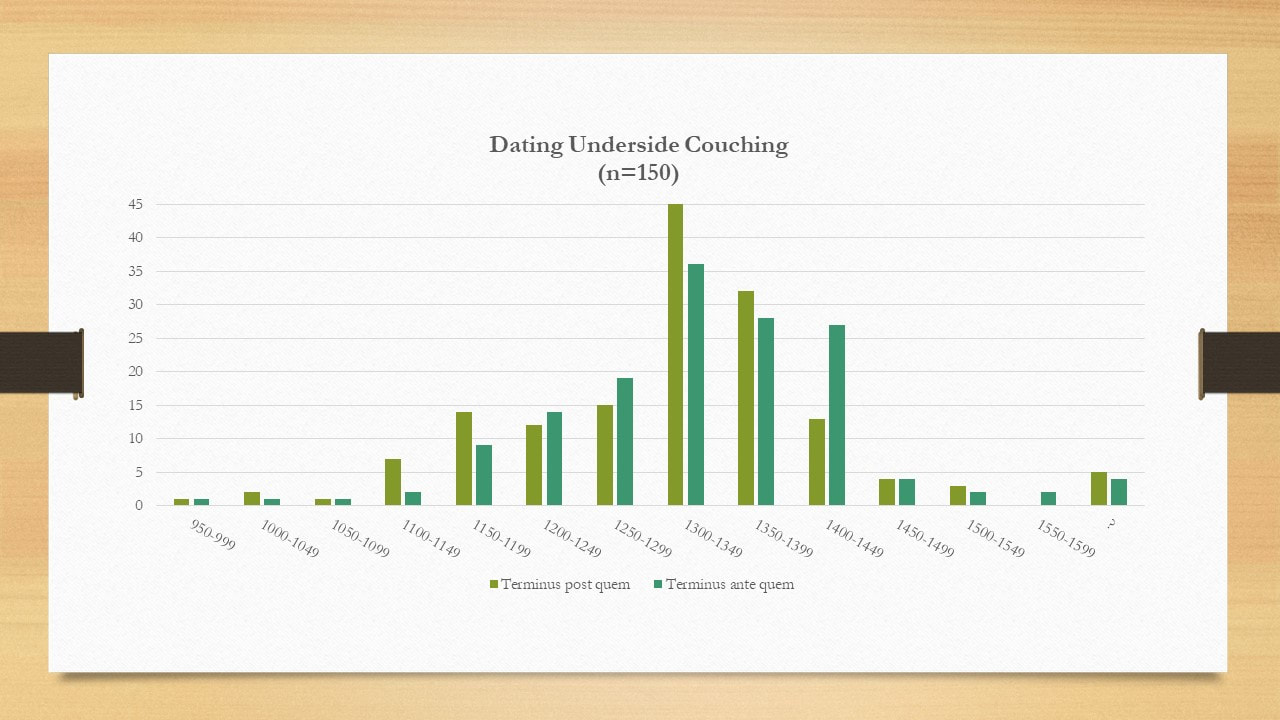

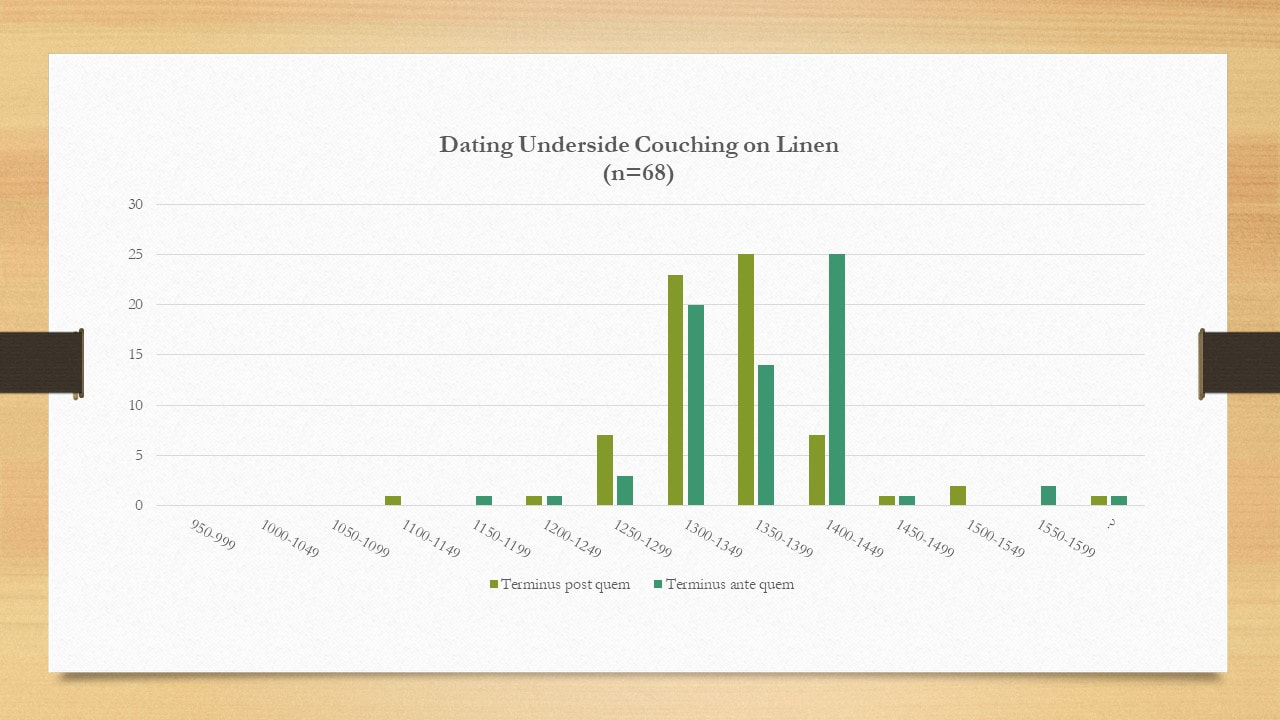

All in all, this book is, at best, a coffee table book. The research essays are not brilliant. For the embroiderer, this book is a huge disappointment and a missed opportunity. No information is added compared to the catalogue entry in "English Medieval Embroidery" from 2016. Should you buy the book? Only if Opus anglicanum is really your thing and you have the cash to spare. Instead, save up for the publications of the Abegg Stiftung and perhaps take some German lessons? Literature Browne, C., Davies, G., Michael, M.A. (Eds.), 2016. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press, New Haven. Michael, M.A. (Ed.), 2022. The Bologna Cope: Patronage, iconography, history and conservation. Studies in English medieval embroidery II. Harvey Miller, London. During my research into medieval goldwork embroidery, I came across a cope held in the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe Bezoeking church in Lissewege, Belgium. Although the beautiful cope hood was made in 1954 by the famous Belgian company Grosse of Brugges, the rest of the embroidery is much older. The literature dates the cope around AD 1500 and the online catalogue even as late as AD 1501-1600! This seems much too late to me. I have a suspicion that the cope is a composite piece. Embroideries from one or more vestments were combined into this new cope. Let me argue my case. For copyright reasons, I cannot incorporate pictures of the cope into my blog. Please click here for the online catalogue. You can change the language to English, French or Dutch. If you scroll down, you can see all the available pictures for this object. You can even download them (and zoom in even more) for private research! Firstly, if we look at the embroidery of the orphreys on either side of the front opening we see that the goldwork embroidery is executed in underside couching. Although the goldwork embroidery is badly damaged it is clearly underside couching. When I pull all the underside couched embroidery from my database of nearly 1500 medieval embroideries it becomes clear that the bulk of underside couched embroidery dates to the second half of the 12th-century until the first half of the 15th-century. The Belgian cope is dated to the (beginning) of the 16th-century and thus seems too late. If you look at the detailed pictures in the online catalogue, you'll see that the saintly figures of the orphreys on either side of the cope's opening have been cut out of the original fabric. They were subsequently appliqued onto the current red velvet and the seams were covered with a piece of twist (note the long linen? stitches that hold it all in place). Originally, these saintly figures were stitched onto linen. My database contains 68 pieces for which the base fabric of the underside couching is one or two layers of linen. These pieces seem to concentrate on the time period from the second half of the 13th-century until the first half of the 15th-century. We've narrowed the time period by about a century. When I saw the embroidery on the orphreys for the first time, they reminded me of the embroidery on the Clare chasuble and that on the Vatican Cope. Both date to the last quarter of the 13th-century. It also has some similarities with the figures on the Syon cope from the first quarter of the 14th-century. The figure of Mary with a lily in one outstretched hand and baby Jesus standing on her lap is very similar to the one seen on the Jesse cope. Also dating to the first quarter of the 14th-century. A date for the Belgian orphreys somewhere between the last quarter of the 13th and the first quarter of the 14th-century seems to be more likely. Just a note of warning: the silk embroidery in these figures is not all original. Just like the goldwork embroidery, the silk embroidery is quite damaged. And whilst the later embroiderers had probably no idea how to repair underside couching, they did know how to silk shade. You can clearly see the difference in the silk shaded areas (thicker silk also) and the original minutely split stitched areas. When the figures were origianlly made, their embroidery was of the highest quality! But there is more embroidery on this cope! The whole 'body' of the cope is 'powdered' with angels, double-headed eagles, fleur-de-lys and a large depiction of the coronation of the Virgin. This is not your classical Opus anglicanum. The goldwork embroidery is executed in normal surface couching and the silk embroidery is executed in vertical silk shading (also known as tapestry shading). These kinds of embroideries are of later date than the 'true' Opus anglicanum orphreys. From the sparse mentions in the literature, it becomes clear that these appliques were mass-produced in embroidery workshops in England and then traded within England and to Continental Europe. Literature from Continental Europe also states that it is likely that these appliques in the 'English style' were also produced locally. As these embroideries are generally considered inferior to 'true' Opus anglicanum, they have so far not gotten the attention they deserve. Their development and therefore their dating is poorly understood.

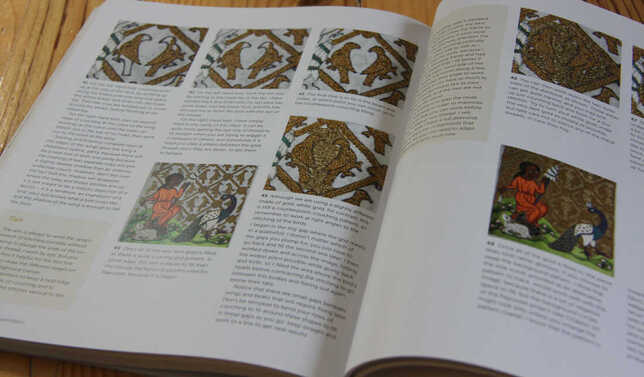

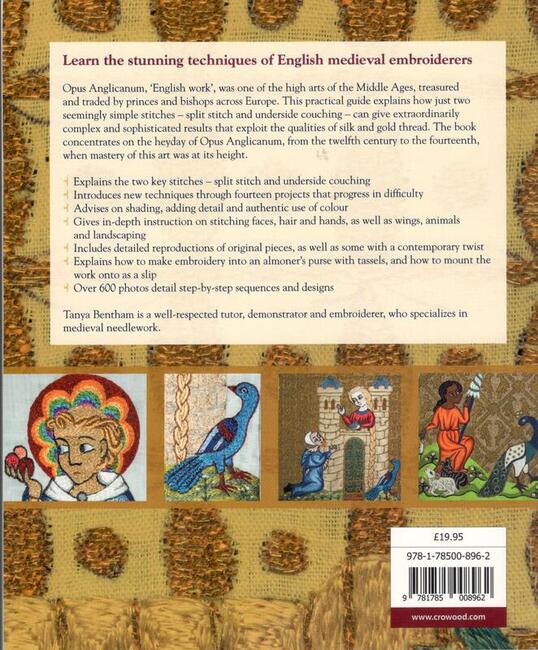

That's all for today. I hope you enjoyed the embroidery on the Belgian cope as much as I did! This piece seems to be unknown in the English-speaking embroidery scene. As I have been invited to study some chasubles in a museum in Görlitz, the next blog will be published on the 21st of March. Literature Browne, C., Davies, G., Michael, M.A. (Eds.), 2016. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press, New Haven. Versyp, J., 1955. "Engels" borduurwerk in het Noorden van Westvlaanderen. Artes Textiles II, 28–33. When I returned from my lovely family visit to the Netherlands, I had one of these pesky little Deutsche Post notes informing me that I had to pick up a parcel in the next village and pay customs duties. As usual, you have no idea which parcel it is until you have paid the outstanding bill and they hand it over to you. To my delight, it was Tanya Bentham's book Opus Anglicanum: a practical guide! I pre-ordered the book as soon as Tanya announced the possibility on her blog. The blog comes highly recommended as the humour with which Tanya both writes and stitches is unsurpassed. I particularly liked her rendition of a medieval watermill with a CCTV camera above the entrance. So let's dive into the book! The book is in essence a paper version of all Tanya's embroidery courses. It is filled to the brim with information and tips from a master embroiderer who has practised her art for many years. Best of all: it is written with the same kind of no-nonsense straight-talking dry humour as her blog is. Things like: "It is slow, too, so, if you need a quick fix, go to do some cross stitch; if you want to get your teeth into something, try opus" in the introduction are not for everyone. However, this is honest advice. You will simply not ever get the same level of mastery as Tanya when you are not equally prepared to sit on your butt and STITCH A LOT. Oh, and don't ever try opus with stranded cotton. Ms Bentham doesn't like it :). The book starts with a chapter on materials, tools and frames. Whilst Tanya stresses that you don't need a lot of fancy stuff to practice opus, it is necessary to use a good (slate) frame that will hold your fabric drum taut (her method of testing with a full bottle of wine is just another version of seeing what happens when a cat sits on it). The next chapter delves into the mighty split stitch. Tanya not only details stitch length but also shows what happens if you still think it is okay to use stranded cotton :). There's also ample information on different types and brands of silk, as well as picking colours. Medieval embroidery is all about the play of light, so what thread you use and how you place your stitches is very important. The split stitch chapter is followed by three project chapters. Each project is shown in clear step-by-step photographs with precise instructions. The projects are tailored in such a way that they increase in difficulty and each teaches you new skills. Opus is not only about the mighty split stitch. Underside couching provides the necessary bling. A whole chapter is devoted to explaining this stitch in depth. And then it is your turn again. Project chapters with (adapted) designs from the Syon cope, the Bologna cope and the Pienza cope give you ample opportunity for wielding your needle. My favourite is "Rumpelstiltskin" with a background of underside couched facing pairs of falcons. Yummy! The last chapters in the book deal with applying your finished embroideries as slips onto something else and assembling an almoner's purse. The last pages are filled with designs drawings and a list of suppliers. As said before, the book is packed with tips and troubleshooting. This shows that Tanya is really at the top of her game. A master is not somebody who does not make mistakes, but who knows how to fix them when they inevitably happen. Everything Tanya knows about opus is in here. No information is kept from you. If you want to sink your teeth into opus, follow Tanya's instructions and practice a lot. Along the way, you will pick up the confidence and skill to work your own masterpieces!

Anything I didn't like about the book? Yes. The binding and the cover aren't very sturdy. This makes a book cheaper to produce (GBP 19,95 is a steal for a 208-page book with over 600 pictures!), but it is a trade-off when it comes to longevity. Furthermore, I would have liked to see a suppliers list with entries for mainland Europe, North America and Australia/New Zealand. After all, this book was not written for UK stitchers only. With protectionism on the rise, knowing where to source materials in your own region becomes increasingly important as shipping costs and customs duties are getting insane. Where to find the book? Please order from Tanya directly! Writing a book does not make you rich. On the contrary. When you order from the writer directly, she/he will get the maximum financial return. Literature Bentham, T., 2021. Opus Anglicanum: a practical guide. Marlborough, Crowood. ISBN 978 1 78500 896 2. At the beginning of January, I and my husband were lucky enough to be able to visit the embroidery exhibition in Paris. Today I'll show you some stunning pieces from the Opus Anglicanum section. The term for this type of embroidery from the 12th-14th centuries translates as 'work from England' and usually consists of very fine silken split stitches and underside couching. It was greatly valued throughout Europe especially, but not solely, for religious purposes. Therefore, you will find these stunning pieces of embroidery in museums all over Europe. But beware: not all Opus Anglicanum embroidery was actually made in England or by English hands. Medieval Europe was already so well connected that both ideas and people travelled a lot. The graves of bishops are a great place to search for medieval embroidery. Bishops were usually laid to rest in their finery in a grave with better preservational conditions than Joe Average. Antiquarians from the 19th century knew that too and when these graves were opened for whatever reason, they brought their scissors along. This is illustrated for instance on a pair of liturgical sandals from a grave from the Cathedral of Saint-Front in Perigueux: three different museums own pieces of the same pair of sandals. Today, many museum visitors turn their noses up when they see these brownish fragments of textile. They are mostly not 'pretty' in the usual sense. But I was very pleased to see that Musee de Cluny devoted a whole display case to these extraordinary finds. For obvious reasons, the levels of lighting were lower than in the rest of the exhibition so my pictures are sometimes a little dark. Nevertheless, look at these stunning patterns of birds and scrolling in very fine underside couching! Another stunning piece of embroidery on display was the above panel with the martyrdoms of the saints. There is a second panel too with female saints. Both are kept in different museums in Belgium but originate from the same church in Namur, Belgium. It was in use as an altar frontal but might have originally been a vestment. The embroidery on this piece is absolutely immaculate and very fine. I particularly love the different goldwork couching patterns in the background and the immense detail on the horse. Although only the above panel was on display in Paris, both panels were displayed at the Opus Anglicanum exhibition in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London a few years ago. One of the biggest pieces of embroidery on display were the fragments of a horse trapper (a protective garment for a horse in battle or tournament). It was unfortunately impossible to capture all (over 20, many quite small) fragments in one picture. The detail of the goldwork embroidery is amazing. The lion's mane and hairy claws are so full of movement through laying the goldthreads in different directions. In amongst the bodies of the lions are many small human figures in courtly dress. They clearly show how to embroider on such a difficult fabric as velvet: cover it with a thin piece of silk. When the embroidery is finished, cut the excess silk away. Although this piece of embroidery comes under Opus Anglicanum it does not show any underside couching and only small areas of split stitch (the silken parts of the claws). Instead, the goldwork is all 'normal' couching and the small figures and the foliage are stitched in running stitch (hence you can see the silk that was used to keep the hairs of the velvet at bay when stitching). It is said that in using these two embroidery methods the actual embroidery would take much less time then when split stitch and underside couching were used. I agree when it comes to the split stitch versus the running stitch. The latter is much quicker as it covers more ground with fewer stitches. However, I am not so sure that normal couching is that much quicker than underside couching. I now practice both and the only marked difference for me is that underside couching is harder on your body due to the slight extra force you need to apply with every stitch. By the way, these fragments have an interesting 'upcycling' story to them. The horse trapper was probably originally made for King Edward III. He was a guest at the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) at Koblenz, Germany, in AD 1338. The horse trapper probably remained in Germany as a royal gift. It was turned into a set of vestments for the Altenberg Abbey. These were dismantled in 1939 to once more show the original horse trapper. There were many more beautiful pieces on display in this part of the exhibition. For those of you who were not able to visit in person, I can highly recommend the exhibition catalogue. It is packed full with good quality pictures and many close-ups. More on my textile adventures in Paris in further blog posts!

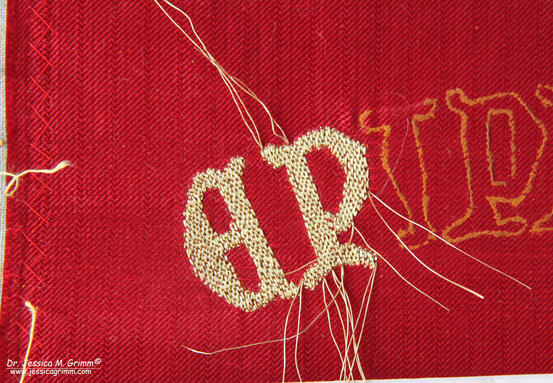

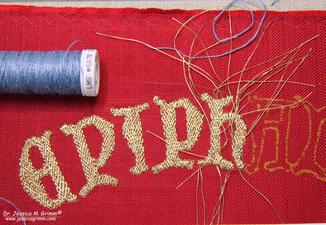

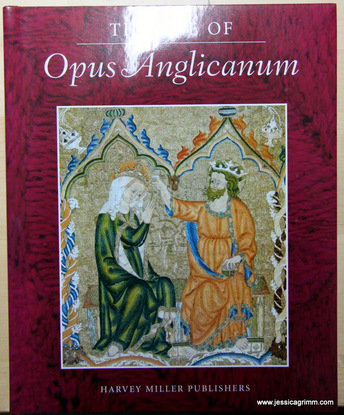

Literature Browne, C., G. Davies & M.A. Michael (eds.), 2016. English medieval embroidery Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press. ISBN: 978-0-300-22200-5. Descatoire, C., 2019. L'art en broderie au moyen age. Musee de Cluny. ISBN: 978-2-7118-7428-6 . Michael, M. (ed.), 2016. The age of Opus Anglicanum (= Studies in English medieval embroidery 1), Harvey Miller Publishers. ISBN: 978-1-909400-41-2. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! For the epigraphy conference held in Munich next week, I am working on several samples of lettering in goldwork embroidery. More information on the conference can be found in part I of this series. Today we will look at the goldwork lettering on the Vic cope made in England between AD 1350-75. The cope was probably made for, but certainly worn by, Bishop Ramon de Bellera of Vic in Spain. It is all worked in underside couching, typical of Opus Anglicanum. When looking for online information on this particular cope, I found the excellent website of the Museu Episcopal de Vic. The website is in English and there is an abundance of information on their textile collection. Amongst which is a lovely video on the Vic cope (see below). This was my first foray into underside couching and I am going to share my explorations with you below. Unfortunately, my stash did not contain a piece of silk velvet, so I opted for red silk with a twill weave. The original underside couching on the Vic cope is done on three layers of fabric: linen, velvet and plain silk. After the embroidery was finished, the plain silk was carefully cut away. My reconstruction omits the layer of velvet. Although the article (see below for a link to the download) on the recent conservation of the cope mentions a lot of details on the materials used, it does not disclose the width of the gold threads used. However, the pictures in the literature suggest a very fine thread. I decided to go with Stech vergoldet 50/60 CS, which is finer than smooth passing #3. It has a width of 0.12 mm. I started by transferring the lettering of the word 'Epiphania' by using the prick and pounce method. This is the original method for pattern transfer and it would probably have been used by the makers of the Vic cope in the 14th century. I deliberately left my Siena water paint a little thick so that I could scrape off mistakes easily. From the pictures, I could tell that the gold threads were actually couched down in pairs. The couching pattern used for the lettering is the traditional basket weave. I would start with a long stretch down the length of the letter and use the twill pattern of the silk to get my spacing correct between the couching stitches. I found this not too easy as you'll need a rather large needle for the linen couching thread. For the first four letters ('epip') I used Fil de lin glace, au Chinois, #40 colour #363 (yellow), which I bought at Maison Sajou when I was in Paris. It is rather thick and not very strong. Even when I changed from a needle #7 to a chenille needle #22, it broke frequently. No matter how carefully I tried to guide the thread through the fabrics. What else could I use? First up was Londonderry linen thread #5070 cornflower 50/3. It is only slightly thinner than the Maison Sajou thread used before. On stitching the 'H', the thread broke three times. This is far less than when I used the Maison Sajou thread. One other thing that eludes me at the moment: what does one do with the tails of the goldthreads? After consulting with a re-enactment lady on Instagram, she said she plunges them and ties them back with the linen couching thread. Sounds reasonable, don't you think? Except for the fact that the stitches on the back are rock solid and I can't weave any thread tails through them at all. Maybe I should use a finer linen thread? Next up was Goldschild 50/3. Although the numbers suggest the thread is comparable in thickness to the Londonderry, it is actually less thick. It did break easily, especially on the small bar-like parts of the 'A'. These parts are really tricky to do as you can't keep the basket weave pattern going. You'll end up with a kind of underside couching satin stitch. The quick turns for both the gold threads and the linen couching threads take their toll. I had one more brand of linen threads I could test: Bockens Knyppelgarn. I started with the rather thin Nel 90/2 and this was no good as it broke every other stitch. But when I tried the thicker Nel 35/2, it was much better. A similar amount of breaks to the Londonderry thread. But again, I am unable to tie back the goldthreads with the linen couching thread on the back. Since I know that medieval stitchers were not averse to using knots, I did the same. Works a treat. So what did I learn from this experiment? Quite a lot actually! Firstly, turning your threads at the design line is done with an underside couching stitch. There is no additional 'normal' couching stitch on top to achieve this. Secondly, underside couching is a bit like constantly plunging. No matter how drum taut your slate frame is, it will lose a bit of tension. Thirdly: my silk did not take the stitching very well. Fibres of the weft were pulled out. Fourth: the stitching is rather harsh on your body. My fingers are all swollen and my back aches (muscle ache). How the flip did they do it back then? They worked through three layers of fabric. That puts even more strain on your body and on the linen threads. I must have some of the parameters wrong. Suggestions are greatly appreciated! Literature

Brow, C, G. Davies & M.A. Michael (eds.), 2016. English medieval embroidery. Yale University Press. ISBN: 978-0-300-22200-5. Calonder, N. & A. Wos-Jucker, 2008. Conservation of the Cope of Bishop Ramon de Bellera, Quaderns del Museu Episcopal de Vic 2, pp. 83-99. Grimm, J.M., 2021. A hands-on approach - Epigraphy in medieval textile art, in: Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., Päffgen, B., Steininger, C. (Eds.), Über Stoff und Stein. Knotenpunkte von Textilkunst und Epigraphik. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, pp. 141–147. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! Me and my husband had a wonderful time visiting London and Salisbury. I bought some lovely silks at the Silk Society and browsed the speciality threads and beads at the London Bead Company. However, we both enjoyed our trip to the Victoria & Albert Museum with the Opus Anglicanum exhibition the most. As not all my readers are in the luxury position to hop over to England to visit this outstanding medieval embroidery exhibition, let's review the excellent exhibition catalogue! The exhibition catalogue 'English Medieval Embroidery Opus Anglicanum' weighs in at a staggering four pounds, has 310 pages with many (and I really mean MANY) high quality pictures. In my opinion, the pictures are the real gem of this catalogue. Not only are they so detailed that you can see the individual stitches, they are also much better in conveying the detail and the vividness of the embroideries than the originals in the exhibition. Because, as always, ancient textiles need protection form light and thus the levels of lighting in the exhibition are nowhere near to those used when they photographed these objects. In addition, many more objects are illustrated in the 7 chapter's texts than were present in the exhibition! Especially those residing in other parts of the world. So who knows, maybe you are living near to one of these gems and you could easily go for a visit! The first chapter details the technical part of the Opus Anglicanum embroidery and when it was in use. It describes the silk split stitching of the figures and the underside couching of the gold threads for the background. I was most surprised to read that medieval gold thread makers were able to make gilt passing only 0.25-0.30 mm thick! The second chapter describes the use of the different embroidered vestments in the Roman Catholic church. It pinpoints Opus Anglicanum embroideries held in museums and churches ranging from Hildesheim in Germany, Vienna in Austria to Chicago in the US. This diaspora has helped the survival of these medieval embroideries after the Reformation. The lives of London embroiderers and the details of their trade are described in the third chapter. Interestingly, in the older records from the 13th and 14th century, women make up the majority of the work force. Then men start to push them from the documentary record. Maybe this had something to do with the craft becoming better organised and the establishment of a guild? A surviving bill shows that women embroiderers were paid far less than men... Chapter four shows that English embroideries were very popular with the papal curia in continental Europe. Examples can be found in the Cathedral treasuries and museums of Italy and Spain. However, by the 14th century, Opus Anglicanum starts to become less fashionable and embroideries from Italy take over. The fifth chapter places the art form of embroidery in a wider artistic context. Many parallels between paintings and embroideries are illuminated. Whereas chapter six looks at the changing embroideries on vestments dating from the second half of the 14th century up to the Reformation. The trade becomes more fragmented with prospective buyers assembling the parts of vestments from different sources. Embroidery is increasingly appliqued onto a background. I best enjoyed the seventh chapter which placed the English embroideries into a wider mainland European context. This greatly enhances my knowledge of embroidery on medieval vestments; particularly from more central European countries like the Czech Republic. The remaining part of the book is devoted to a thorough catalogue of all the pieces in the exhibition. Beautiful detailed pictures provide a rich banquet of eye candy! The best of the best? The Toledo cope from AD 1320-30 covered all over with saints, scenes of the life of the Virgin and wonderfully detailed birds. This is my absolute favourite; don't you agree? The catalogue is widely available through online sources like the V&A shop and comes at a price of 35 GBP or about $ 75. And then there is another brand new book on the topic, also available from the V&A: The age of Opus Anglicanum. It contains nine scientific papers on the subject, mainly written by the people who also contributed essays aimed at the general public to the exhibition catalogue. I haven't read it yet, but if you are also, like me, interested in a more thorough covering of the subject, this might be worth its 89 GBP or $ 143. However, the quality of the pictures is much better in the catalogue. More interesting however, is its promise written on the inside sleeve: 'This volume, the first to appear in a series on English Medieval Embroidery...'. Yeah, bring them on good people of the V&A!

So, for a number of you, my dear readers, it is now time to prompt Santa to make sure you find a copy of the exhibition catalogue under your Christmas tree :). On a more personal note: sadly, upon our return from England, my husband was told that the company he works for closes its archaeological department. Not the sort of Christmas' present we wished for, I can assure you. As I now help him in finding a new job, it will undoubtedly impair on the time I can spend on my own embroidery endeavours, but I will try to keep my weekly blog posts upright! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed