|

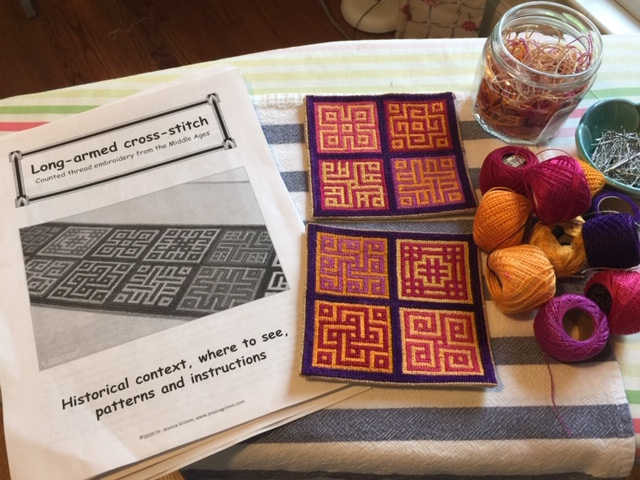

I was delighted when Gina sent me pictures of her biscornu showing some of the long-armed cross-stitch patterns from my latest eBook. Gina filled her biscornu with dried lavender. This is an excellent way of using these beautiful medieval patterns and stitch!

3 Comments

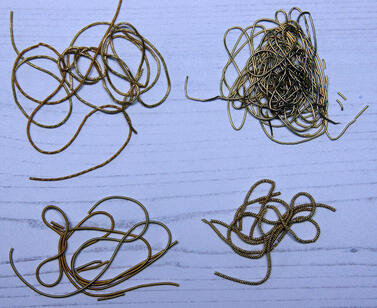

During the zoom-meeting on Saturday evening for my online goldwork class 'Imperial Goldwork Course' we stumbled upon the sizing systems for metal threads. Some students from the US had trouble finding the correct sizes of purls mentioned in the PDF-handouts as they claimed that the sizing system in the US is different from that used in Europe. They mentioned that on the websites of Garibaldi's Needleworks and Berlin Embroidery the sizing would run in such a way that the higher the number the thicker the metal thread. This was opposite to my sizing system mentioned in the PDF-handouts. This was new to me. Immediately after class, I started to investigate. However, on the aforementioned websites, I found exactly the same measuring system as I was using. After a while, I realised what had happened. A quick email to the said students confirmed my suspicion. It was a stark reminder that, for somebody starting with goldwork embroidery, it can be a jungle out there! Let me clear the confusion. In the first eight lessons of the Imperial Goldwork Course, we learn about the different forms of cutwork used in 19th-century goldwork embroidery. For cutwork you normally use: smooth purl, rough purl, wire check and bright check. These purls have a sizing system that runs from #4 (the wire with the largest diameter) to #10 (the wire with the smallest diameter). For the course we use the larger #6 and the smaller #8 as they are the two most commonly used sizes. An opposite sizing system is used for pearl purl. It runs from Very Fine (the wire with the smallest diameter) to #3 or #4 (the wire with the largest diameter) depending on the manufacturer. Said students had previously worked kits with pearl purl in them and logically assumed that the higher the number the fatter the metal thread. One word of warning here: whilst the sizing system in the English-speaking world is the same for metal threads, the sizing system in the German-speaking world is different. Although I am based in Germany, I use the English sizing system as it is the most common system used by goldwork embroiderers. Oh, and the French system differs too :). Another student mentioned that it would be a wonderful idea if I would measure the diameter of the purls the students need to use and then tell them that number instead of the sizing system commonly used. Although I mentioned that my gut feeling was that this would be rather cumbersome for a number of reasons (measuring accuracy would be difficult to maintain and all students would need high-speck calipers too), the said student was not convinced. What does every good teacher do? Investigate! Here we go. As I have been an archaeozoologist for 15 years and measured 100-thousands of animal bones with scientific digital calipers, I still had several pairs laying around the house. The pair I used are made by Milomex Services in the UK. The measuring range is 0-150 mm with a resolution of 0.01 mm. Measuring accuracy is: 0-100 mm +/- 0.02 mm and 100-150 mm +/- 0.03 mm. This means that if you measure something that's between 0 and 100 mm the inaccuracy is +/- 0.02 mm and for something between 100-150 mm it is +/- 0.03 mm. As the smaller purls have tiny diametres, this measuring accuracy is potentially important. Apart from the measuring inaccuracy innate to the calipers, there is the problem of the metal threads being rather soft compared to the tips of the caliper. It is therefore rather easy to squash your metal threads ever so slightly and getting a wrong (lower) diametre. To prevent the very pointy tips of the caliper to slide between the coils of the purls, I placed the purls between the broader parts of the caliper's tips (see picture above). To further try to minimise the measuring error caused by the relative softness of the metal threads, I took multiple readings of each wire sample and noted the average. What were my findings? As my gut feeling told me and the measurements confirmed: samples from different manufacturers can differ. Even different samples from the same manufacturer can differ. What are the sizes of the most common metal threads used according to my measurements? - gilt or silver-plated bright check #6: 1.1 mm - gilt or silver-plated rough purl #6: 0.9-1.1 mm - gilt or silver-plated smooth purl #6: 0.9 mm - gilt or silver wire check #6: 1.2-1.3 mm - gilt or silver-plated bright check #8: 0.9-1.0 mm - gilt or silver-plated rough purl #8: 0.7 mm - gilt or silver-plated smooth purl #8: 0.7-0.8 mm The results are discrete enough that it is possible to distinguish between #6 and #8 purls when you accurately measure their diametre. Can these measurements assist you when you want to buy goldwork supplies? Not so much. For instance, on the website of Berlin Embroidery you will find that the measurements are approximately: - gilt or silver-plated bright check #6: 1.5 mm - gilt or silver-plated rough purl #6: 1.5 mm - gilt or silver-plated smooth purl #6: 1.5 mm - gilt or silver wire check #6: 1.5 mm - gilt or silver-plated bright check #8: 1.0 mm - gilt or silver-plated rough purl #8: 1.0 mm - gilt or silver-plated smooth purl #8: 1.0 mm As Tanja Berlin and I use the same goldthread suppliers, her measurements should have been exactly the same as mine. Instead, they differ (she probably used a ruler to measure the purls). As a beginning goldwork embroiderer, what would you have bought from for instance Berlin Embroidery when I would have told you that we are going to use a gilt smooth purl with a diameter of 0.9 mm? You would probably have ordered a #8 from Tanja Berlin's website and then have ended up with a wire that could have had a diameter 0.2 mm smaller than I am using. This does not sound like much, but it makes a huge difference. By just ordering the #6 as stated in my PDF-handout you would have ended up with the correct thread. That's why we use the numbering system instead of accurately measuring the diameter of the threads. Besides, not all goldthread suppliers state the diameter nor do most teachers or books. And as every good scientist should do, you can find the raw data in the document below.

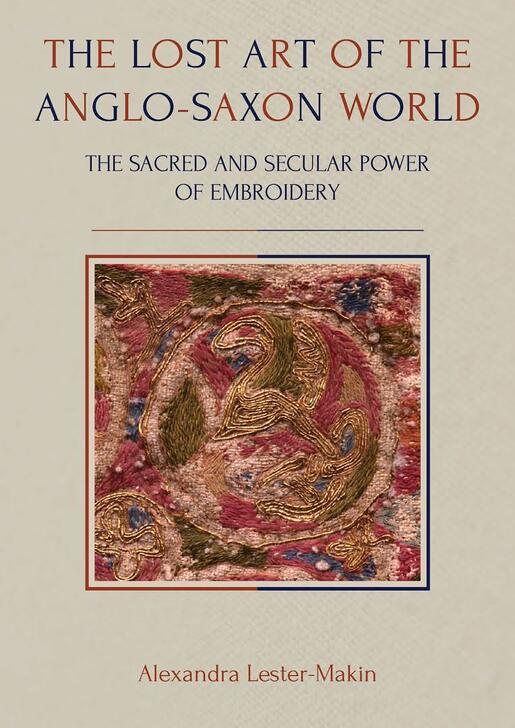

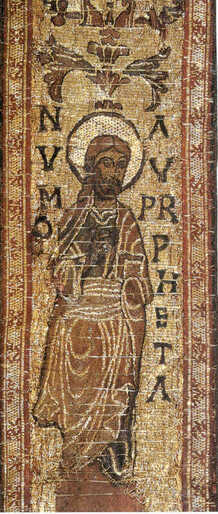

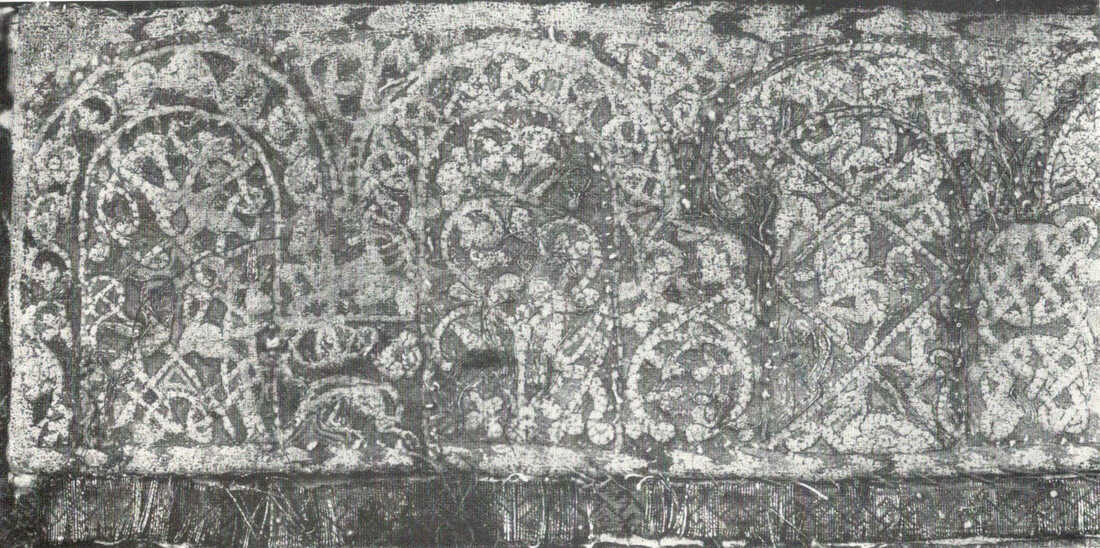

Book review: The lost art of the Anglo-Saxon world. The sacred and secular power of embroidery.15/6/2020 For most of you, it will come as no surprise: I am a book lover! And many of you regularly mention books on embroidery to me which would be worthy additions to my library. The lost art of the Anglo-Saxon world by Alexandra Lester-Makin is one of these latest additions. It isn't a project book, but a properly published PhD-thesis. Don't let that scare you. As Alexandra is both an archaeologist and a Royal School of Needlework apprentice this makes for an interesting read. Research into other art forms, such as painting and sculpture, never goes out of fashion. Researching embroidery and its makers seems to go through cycles. At the moment we clearly experience a renewed interest in this often under-appreciated art form. The book is divided up in six chapters and comes with an elaborate catalogue. After a chapter on the introduction of Anglo-Saxon embroidery comes a chapter on the data and its difficulties. As you probably already knew, there isn't much embroidery left from the Early Medieval period (c. AD 410-1066 for the British isles). For the more than 600 years under scrutiny, there are only 41 embroideries to work with. Of these, only three are more or less complete: the Cuthbert embroideries from Durham, the Maaseik embroideries in Belgium and the Bayeux tapestry. All other embroideries are fragments. In some cases, only the holes have survived and not the embroidery thread. In other cases, there is no original material left as we deal with an imprint on a metal object (mineralisation) or complete carbonisation due to fire. Oh, and then there are the fragments that are unavailable for inspection as they are either too fragile, mounted in such a way that they are inaccessible or they have simply vanished... Precisely dating them is often a problem too. As a fellow archaeologist who worked with animal bones instead of embroideries, I was rather sceptical when I realised the data set the research is based on is so small and wrought with so many difficulties. Would I have written my PhD-thesis on 41 samples of animal bone of which were three more or less complete skeletons, the rest fragments: either burnt, inaccessible or lost? Often only broadly dated. And then come up with a coherent story on husbandry, hunting, fishing, trade and bone working over a period of more than 600 years in all of Germany? Nope. Instead, I had thousands of bones, in very good condition, many well-dated and almost all available for my inspection. Still, I wasn't able to do more than draw tentative conclusions and hypothesise on animal keeping and the use of animal products in medieval Emden. Does this mean that I think Alexandra did a bad job? No, not at all! But comparing her archaeological data set to mine hopefully shows you how little it is we really know. And that Alexandra had to come up with a theoretical archaeological framework to be able to extract as much information from each data set entry as she could. That she did rather brilliantly! In chapter 3, Alexandra shows us in great detail how she extracts as much information from an embroidery fragment as she possibly can by writing its object biography. In this object biography, she includes detailed technical analysis, careful study of related attributes and context, and related documentary evidence. And that for the whole life-span of the fragment up until the present day. Being both an archaeologist and a professional embroiderer, Alexandra is very well equipped to undertake this kind of research. With this theoretical research framework in place, she then analyses all the embroideries at her disposal. The results form the basis of chapter 4 (Embroidery in Anglo-Saxon society) and chapter 5 (Early medieval embroidery production in the British Isles). And I am quite impressed with the ideas she comes up with. For instance, although there are not many written sources on the training of professional embroiderers in the early medieval period, careful analysis of stitch length and execution leads her to conclude that the embroiderers must have had extensive training to be able to achieve the level of perfection they did. Or giving us archaeologist something to think about when we excavate a dwelling site. Could a certain building have housed an embroiderer? Is there enough natural light coming in? Can it be kept clean? Not necessarily lines of thought an archaeologist or an art historian would have come up with. Other conclusions she draws regarding the use of certain types of stitches going in and out of fashion, I find harder to justify with the patchy nature of the data set. Although they seem to correlate with the pagan versus the Christian nature of society, we should not forget that this might be pure coincidence and might well change when further embroidery fragments are unearthed. That said: I like the idea of looped stitch being viewed as the mythological serpent that both protected the pagan wearer and the seam from coming apart. Personally, I have learned a lot from reading this book. Too often I am reluctant to publish my own embroidery research as I feel that my database is too patchy. Alexandra's research approach has given me an opening on how to extract more information from my database. And she has given me the guts to put my findings out there despite the patchy nature of the database. After all: if you don't put your hypotheses out there for contesting, you are not helping to advance the research of historical embroidery. Alexandra did and does.

Literature Browne, C., G. Davies & M.A. Michael (eds.) (2016) English medieval embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. London: Victoria & Albert Museum. Grimm, J.M. (2010) Animal keeping and the use of animal products in medieval Emden (Lower Saxony, Germany), self-published. Lester-Makin, A. (2019) The lost art of the Anglo-Saxon world: the sacred and secular power of embroidery. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Schuette, M. & S. Müller-Christensen (1963) Das Stickereiwerk. Tübingen: Wasmuth. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed