|

Research into professional embroidery goes in and out of fashion. At the moment, it is clearly in fashion with many new exciting publications becoming available in Germany, France and Italy. In many cases, their analysis of the embroidery trade in the medieval period depends on a few older sources. One of these famous sources is Goetz 1911 on the silk embroiderers of Munich. Unfortunately for most of us, it is written in German with the added difficulty of being printed in Frakturschrift. And since it was written more than a hundred years ago, it is quite difficult to get hold of. A few weeks ago, I was able to buy a second-hand copy! And I started to translate it into English. Being originally written in old-fashioned German with at least half of it in medieval and early-modern German, translation was slow. And since these older versions of German are even more fond of VERY long sentences, the resulting English is not always pretty. But it will do! A PDF of the result is available at the end of this blog article :). So far, I have not been able to find out who the writer, Ms Gertrud Goetz, was. Since her article was published in the Journal of the Historical Society of Upper Bavaria, she was probably a member there. And the fact that she had access to the original historical sources and could decipher them, points at her being a historian or similar. The resulting article is really informative and quite lovely to read. One gains a lot of insight into the lives of embroiderers from the 15th- till the 18th-century. Throughout the centuries, three main adversaries tried to mess with the official embroiderers of Munich: women, people from Augsburg and the French. Some things never change, LOL. No seriously: this is actually really sad. Although the guild regulations of Munich are often quoted to prove that women were allowed to embroider, when you read the original texts, a different picture emerges. One we already know from the guild regulations in the Netherlands. Women were not excluded from the embroidery guilds, but in real-life they just did not become master craftswomen nor do we see them individually in official documents related to the guilds. Only one of the Munich historical sources mentions a woman: a master's widow with her son. And guess what: she is not playing by the rules. Neither are the others. But she is perceived as a problem. From what I deduct from the sources, the picture that emerges is this: In the beginning, the professional embroiderers of Munich were all male and they worked for the elite and the church. Since Munich was rather a large village than a metropolis, there was never really enough of this employment. The male embroiderers needed to supplement their schedule with 'simpler' work. Unfortunately for them, this was already the realm of women. One such item made by women was the Riegelhaube. This is a heavily gold-embroidered bonnet typical for the folk dress of the upper-middle class. In 1793, the only leftover embroidery master of Munich, Jakob Gelb, tries to forbid these practices by pressing the city council to hold a police raid. He even hands in a list with the addresses of the culprits. All women and a single man. And Jakob is not an unreasonable man: he demands that he can pull any of these illegal embroiderers in as workers when his workload demands it. Instead of giving them the same full rights to exercise the embroidery trade as he holds them, he wants these women to work for him when he so desires... Only three decades later, this results in new trade regulations for Bavaria. From now on, embroidery is a free trade exclusively executed by women. The reason for this: just like with other female occupations, embroidery is an occupation that does not require training nor learning. Just so you know! In order for you to study the original sources for yourself and to draw your own conclusion, please find a PDF of the original publication and my crude translation below:

Literature

Goetz, G., 1911. Die Münchener Handstickerei zur Zeit der zünftigen Gewerbeverfassung (1420-1825), Altbayerische Monatsschrift 10 5/6, p. 107-114. Wetter, E., 2012. Mittelalterliche Textilien III Stickerei bis um 1500 und figürlich gewebte Borten. Abegg Stiftung: Riggisberg. P.S. The publication mentions a roll of coats which contains eight coats of arms of embroiderers. These coats of arms display broche/brodse/Bretsche. Unfortunately, the name of the document is so vague, that the librarian of the Bayrische Nationalmuseum so far could not identify it.

11 Comments

As most of you know, I do love cross-stitch. For me, it is the perfect antidote to working goldwork replicas of medieval pieces. Especially when that cross-stitch comes in the form of a kit. After all: somebody else has done all the thinking for me. I just need to follow the instructions. So when I saw the gingerbread mice by 'Just Nan' on Janet Granger's blog, I knew this was going to be the beginning of a new collection :). For those interested: I also collect the Mill Hill Santas. Since Janet showed off the gingerbread mice, I am going to show you the snow mice. Not care for snow nor gingerbread? Do not worry! 'Just Nan' has birthday mice and Halloween mice too. And a whole lot of other beautiful cross-stitch designs that are quite unusual. My mice came from 'Create Nostalgia' in the UK. Owner Mary Gittins provides a terrific and speedy service. These are Mr and Mrs snow mouse. However, they have posher names too: Crystal Snowlady Mouse and Frosty Chillingsworth Mouse. Mrs mouse is the more intricate one to stitch and takes a bit longer. If you set your hands to it, you can stitch and finish a mouse a day. The finishing is easy, but a bit fiddly. After all, the mice are only 4,5 cm tall. Apart from cross-stitching (over two and over one!) on 32 ct linen, you will do some beading too. I think these designs are pretty genius and intricate. Now, these mice are not sold as complete kits. And to me, that's a bit of a downside. For starters, my stash does not include a range of white and coloured 32 ct linen. That's too coarse for medieval goldwork embroidery. So I started by ordering pre-cuts for all my mice. After all, this is going to be a collection :). I did not bother with ordering the correct numbers of DMC stranded cotton or Kreinik metallic threads. I happen to have quite a few of them. Seldomly the correct numbers. However, I had a pretty clever stitching grandma who once told me that since Santa is primarily red, white and black, it does not matter if you use 321 or 666. Very good stitching advice indeed and works well for mice too. The patterns do include the beads, sequins, tails, stick arms, button and hats. Whilst there are enough beads in the package, the other elements only make you one mouse. And these are potentially parts that are not so easy to source. But I am pretty sure that there will be people in my inner circle who see my mice and start begging for one too. Since I am not going to give my prized collection away, I will have to come up with some clever substitutes. My husband will probably transform from head graphics to head mice tail maker :).

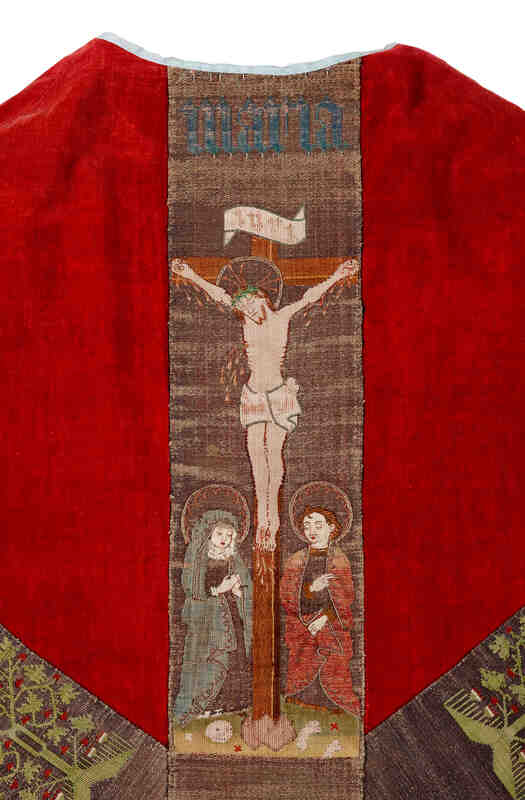

Whilst I really think these mice are pretty cleverly designed, there is one part on them that I am not too sure about: the mouse's bottom. It consists of a decorated metal button. You are supposed to attach it over the stuffing opening (this is getting hilarious!) with whipping stitches. As the button is shaped irregularly, your stitches cannot be regular. That bugs me. Buttonhole stitches with a thicker thread such as perle #12 or #8 look a bit better. However, it is still not the prettiest part of the mouse. I have had mice butts on my mind for days by now, but have not found a better solution yet. Any advice? A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a blog post about the unusual orphreys of St. John I had seen in the Dommuseum of Fulda and in a catalogue of the Dom treasure of Frankfurt. As said, I did write to both museums to see if they had more information on the pieces. The writer of the catalogue of the Dom treasure, Dr. Karen Stolleis, is an art historian specialised in liturgical vestments. She was contacted by the Dommuseum Frankfurt, but already knew of the loose orphrey in the Dommuseum Fulda. Both museums were very helpful in providing me with good pictures and all the information they have on the pieces. Unfortunately, the coat of arms on the loose orphrey in Fulda has so far not been identified. Dr. Karen Stolleis believes that the unusual orphreys with their silken backgrounds were inspired by the famous Kölner Borte. But what are they? Here you see a chasuble (ABM t2011) held at the Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, the Netherlands. It was made in Cologne between 1425-1450. The original red velvet is decorated with woven bands. These are the so-called Kölner Borte. They are typically between 6 and 15 cm wide and made in Cologne from the 13th- till the 16th-century. The warp is made of linen and the weft of coloured silks and membrane gold. In addition, details can be added with embroidery. For my own research, I largely ignore the Kölner Borte. It is very hard to determine if certain details are woven or stitched. Especially when working from pictures. And catalogues, mainly written by art historians, aren't always clear in their attribution. A typical Kölner Borte shows writing in Gothic lettering and can also show scenes such as the crucifixion or a saint. The parts with the letting (often 'Maria' and 'Ihesus') and rosettes or abstract trees are often repeated. These parts could be created in advance and combined with a more unique band. In this case a band with the crucifixion, James the Great, Peter and the coat of arms of Katharina van Kleef (1417-1476). When people think of the Netherlands, they commonly refer to 'Holland' with the city of Amsterdam. And indeed, during the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th-century, this was and still remains one of the most important economic parts of the Netherlands. However, during the Middle-Ages, the Duchy of Guelders (present-day province of Gelderland, large parts of the province of Limburg and North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany) was an economic powerhouse and a global player. With a ruling dynasty to match. Think the Tudor dynasty is 'interesting'? Meet this lot ...

Katharina van Kleef married Arnold van Egmont (1410-1473), Duke of Guelders, when she was only 13-years old. She was an extremely good match for 20-year old Arnold. Through her mother, Mary of Burgundy (1393-1463), she was a niece of Philip the Good (1396-1467). Katharina's and Arnold's daughter, Mary of Guelders (1429/1434-1463), married James II of Scotland (1430-1460) and became the great-great-grandmother of Mary Queen of Scots. Just saying ... Meanwhile, Arnold wasn't very good with money nor with managing the conflicting loyalties in his own family. When his wife and her uncle, Philip the Good, met and hacked out a plan to get the larger cities to revolt, son Adolf was put on the throne and Arnold imprisoned. The pope wasn't amused and excommunicated Adolf. Years of unrest followed, the House of Burgundy got more and more involved in Guelders' affairs and pursued her own interests. Arnold died first, then Adolf and in the end, the Duchy of Guelders became part of the Spanish Netherlands in 1556. Nominally, the Duchy of Guelders continued to exist until 1795 but was never to be independent again. I still feel the pain. By now you must have guessed that I was born in Gelderland :). Literature Leeflang, M. & K. van Schooten (eds), 2015. Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden. Utrecht: Museum Catharijneconvent. Stolleis, K., 1992. Der Frankfurter Domschatz Band I Die Paramente. Kramer, Frankfurt. P.S. Want to know more about the Duchy of Guelders and its rulers? The YouTube channel of the 'Ridders van Gelre' provides you with the other history of the Netherlands. Accurate, but always with tongue in cheek. As part of my research into medieval goldwork embroidery, I read many collection and exhibition catalogues. Most are written by art historians and only a small proportion by, or with the help of, textile curators/conservators. Most texts are therefore only partly useful to the embroiderer. The gold-standard, in my opinion, are the books published by the Abegg-Stiftung. One of the aspects of medieval embroidery that particularly interests me is the pattern transfer. As far as I know, there has never been a systematic review of the substances found on these textiles that result from the initial pattern transfer onto the fabric. More recently, detailed chemical analysis did take place for some of these medieval embroideries (for instance the vestments from Bamberg, soon to be published). More commonly, you will find vague references in these catalogues to the materials used for pattern transfer. Either ink or paint. But last week, I came across the silverpoint. The silverpoint consists of a piece of pure silver mounted on a handle. You can buy them from well-sorted art supply shops. Silverpoints were used by medieval scribes and have been used by some artists till the present day. Silverpoints are the predecessors of our modern lead pencil. But contrary to a lead pencil, the silverpoint will not work on normal paper. The paper, or for that matter vellum, needs to be prepared with chalk and/or egg yolk (or similar products). The chalk makes the surface rough so that small particles of silver are shaved off the silverpoint and the egg yolk contains sulfur that oxidises these particles so they turn from faintly visible grey to dark brown or black. The air oxidises the silver particles too, but the egg yolk seems to speed up the process. The silverpoint intrigued me and I wondered if it could indeed be used to transfer a pattern onto fabric. Linen is a little raw, so I hoped that I could just scribble onto it. Nope. No lines visible. No further oxidation on the air after a few hours or even days. And I am not at all keen to go the sulfur (egg yolk) road. Because the sulfur will also tarnish my goldthreads as a large part of their composition is silver too. Does this mean the silverpoint could not be used for pattern transfer? Or does it mean that I need to prep my linen in a different way? Any ideas more than welcome!

I read about the silverpoint in the catalogue on the collection of the Schnütgen Museum in Cologne. It was published nearly 20 years ago by Dr Gudrun Sporbeck, an art historian. Apparently, the body of Christ on a chasuble cross with inventory number P223 is drawn with a silverpoint onto the linen. Did she determine this? Or did she copy from the older literature stated? The older literature in which this particular chasuble cross has been described dates from 1888 till 1938. Was it just something that was assumed? Did somebody do some chemical analyses? Only one way to find out: ask her. So that's what I am going to do. Will keep you posted. Update: I contacted Dr Gudrun Sporbeck repeatedly, but never received an answer. In addition, Enikö Sipos also experimented with the silverpoint on textile and came to the same result as I have: it doesn't work. Literature Sipos, E., 2005. Proportions and measurements. The making of the chasuble. In: Kovacs, T. (ed.), The Coronation Mantle of the Hungarian Kings, Hungarian National Museum: Budapest, p. 91-107. Sporbeck, G., 2001. Die liturgischen Gewänder 11. bis 19. Jahrhundert (=Sammlungen des Museum Schnütgen Band 4), Museum Schnütgen: Köln. Wow, my course filled up within three minutes last night. That's brilliant for me :). But I do realise that quite a number of people, unfortunately, missed out. Many of you have sent me an email to ask when the course will re-run, if they can be put on the waiting list or if they may attend without a kit. I have emailed all of them individually but I think it would be a good idea to publish the answers here as well. First: Will there be a re-run of the course? Honestly, I don't know yet. The interest is there and this is not the problem! But sourcing the materials during a pandemic is. Although I started placing orders more than a month ago I cannot ship out the kits today. Normally, Zweigart linen fabric is on next day delivery as it is being produced here in Germany. As it did not arrive more than a month ago, I started calling them. The phone wasn't picked up for days. Finally, they emailed me to say that delivery will not be before the middle of November! Still plenty of time to send out the kits :). Another example: paint produced in Germany. To get 15 tubes, I had to order from five different sources. One source being particularly cheecy as it turned out they did not have the stuff and had to order in from the manufacturer! Brushes the same thing. Some silks too. And, oh yes, the freshwater pearls too. Even with a four months period between ordering the materials and the start of the course, I probably could not have sourced all materials for more than 15 kits. Second: Will there be a waiting list? No there won't. Because of the above pointed out supply difficulties I simply cannot say if the course can run again in its present form. And I do not want to give out promises I cannot keep. Thirdly: Will you allow students to attend without a kit? No, I won't. From the questionnaire send out after the Imperial Goldwork Course it became clear that students did not like the fact that there was no kit. Sourcing your own materials during a pandemic (and even without!) is a nightmare. They also stated that the small classes on Zoom were a blessing and very much appreciated. I, as a tutor, never liked larger classes. You have no idea what some people are up too when you turn your back on them for only a very brief moment :). For 'live and in the flesh teaching', I limit the numbers to about 10. When organisers push me to take on more, I am not a happy bunny. As a student, I do not like to sit in big classes either. I am far too polite :). The ones who scream the most and the loudest get their money's worth of teaching. I, as a student, end up figuring it out for myself. No matter how experienced the teacher is, there is a limit to the number of people you can teach successfully.

So what is the way forward? As long as the pandemic rages: take it step by step and don't plan too far ahead. I don't know about you, but I found these past seven months exhausting! Learning so many new things in such a short span of time. Not knowing if I would be able to find a way to earn money when all the teaching was cancelled was scary. The many extra hours and worries took their toll. My body didn't like me punishing it that much and started to rebel. My body is way wiser than I am! I stopped working all hours, set some boundaries and I quit Instagram. Instead, I try to make sure that I get enough exercise, work on my art (I haven't seen St. Nick in over a year!) and support my husband as much as I can as he is presently swamped in work. What that will mean for you? Excellent news in fact! It means that my head is free again to come up with fresh ideas for future classes. But the classes will not be taught back to back. There will always be enough breathing space for me in between classes. I need that. I am not a machine. So get on my mailing list for my newsletter and keep an eye on this blog for announcements of future courses. They will always have limited spaces and come with a kit. This will ensure that you don't have the stress of sourcing hard to get items and in class, you will not have to shout for attention either :). |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed