|

German medieval embroideries are often characterised by a composite thread not seen elsewhere: gold gimp. This is a relatively thick piece of string wrapped with a thin thread of membrane gold (gilt animal gut wrapped around a linen core). Was this a ready-made thread? Did the embroiderers make the thread themselves? Is it either pre-made or made during the actual embroidery? Let's see if we can find the answers! Here you see a detail of the Nativity scene from the chasuble kept at the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg. The nimbus is edged with this composite thread: gold gimp. Here's a close-up of the gold gimp. The wrapping isn't very neat. But what is more puzzling: there are no couching stitches to attach the gold gimp to the background fabric. The membrane thread isn't used to do this either. Firstly, it would be far too fragile to endure being pulled through the fabric multiple times. I've worked with recreated membrane threads, and they definitely do not hold up to this kind of abuse. Secondly, you can tell from the above picture that the membrane thread is wrapped around the thick string and does not penetrate the fabric. And what about the 'mess' on either end of the gold gimp? What's that all about? And then I remembered that Alison Cole had written about making silk gimp before it was commercially available. She describes a method whereby you make that composite thread whilst you embroider. Let's see if that works. The ratio of string to membrane gold is about 5:1. From my experiments with the recreated membrane gold, I know that it is more similar to Japanese thread than to passing thread. But it isn't the same. Its core is made of linen instead of cotton, and the spinning direction is opposite.

Trying to recreate gold gimp wasn't entirely successful. It works, but it isn't very neat. And it is very fiddly to do. Nevertheless, I did learn a few things. Firstly, it is possible to hide the couching thread completely. Especially when you use a very thin linen or silk thread for this (mine was a bit bulky). Secondly, the thick string should be as firm as possible. Cotton string worked less satisfactorily than stiff, non-squidgy linen string. And thrirdly, one should leave a tail of the gold thread at the start. This can be used to wrap the plunged string at the start. Just as I was able to do at the end. My little experiment also hints at the impossibility of producing a gold gimp as a pre-made thread. The wraps would come undone as soon as you take off tension. You would need to glue them onto the string to prevent this from happening. And I don't think there is glue in these threads. The glue would adhere to the thin membrane and tear the fragile thread apart as soon as you manipulate it to work with it. Any thoughts?

12 Comments

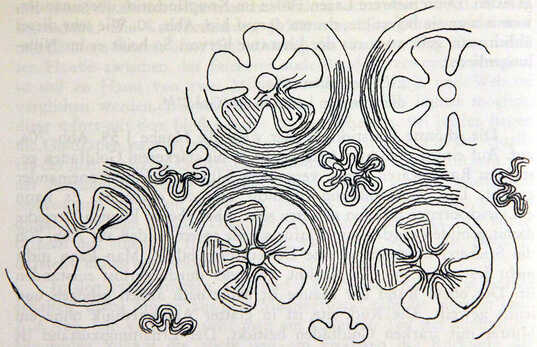

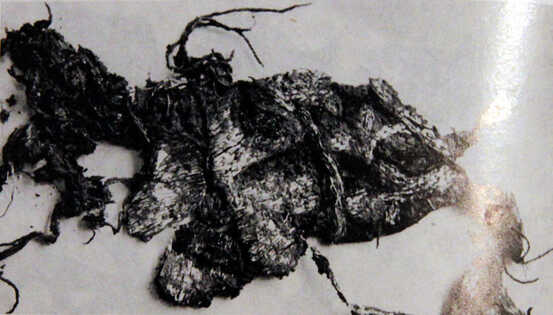

The majority of medieval goldwork embroidery is ecclesiastical showing corresponding iconography. A tiny proportion of surviving pieces can be associated with the nobility and might show non-religious designs. Absolutely unique are the finds of Villach-Judendorf in Austria near the Slovenian border. Archaeological excavations in 1968 revealed the graves of people who had been buried during the Hallstatt era till the high Middle Ages. Among the younger graves were at least four women who were buried wearing a bonnet with goldwork embroidery. The finds were extensively published in 1970 by Ingeborg Petrascheck-Heim. As far as I am aware, no newer publications exist. So out comes my lovely, always grinning, assistant Elisabeth to make sense of the black-and-white pictures in this important publication. How come so few examples for "normal" goldwork have survived from the Middle Ages? Gold can be recycled without quality loss. This means that worn clothes were deconstructed or simply burnt to retrieve the bullion. In addition, you needed a certain amount of disposable income as goldthreads, even the gilt ones, were quite expensive; the majority of the population did not have access to them. And even when people were buried in their goldwork-finery, only in exceptional circumstances did these textiles survive. Your best bet would be a sarcophagus in a cosy, slightly drafty, family vault. However, sarcophagi and family vaults are a rather expensive luxury reserved for higher-level clergymen and the nobility. Thank goodness for silver-gilt threads! Upon burial in the ground, the humidity and the larger silver component in the threads form salts that leak onto the surrounding area. In the case of goldwork embroidery, this is the textile component of said embroidery. The salts preserve this textile component. And although we will not end up with complete pieces of clothing as sometimes is the case in sarcophagi, the salt-caked fragments can still tell us a lot about the original goldwork embroidery. This is the case in Villach-Judendorf. Let's examine the four graves with the goldwork bonnets in some more detail. First up is grave J 57. Even with the help of my lovely assistant, I, as a former archaeozoologist, found it hard to correctly orientate the pictures in the article (see above). I think the suture on the left in the black-and-white picture is the one between the frontale and the parietale. The bonnet sits on the back of the head and the face (bones not preserved) would be towards the bottom of the picture. Amongst the textile remains you see in the above black-and-white picture is a black woollen bonnet with a design consisting of a nine-part trellis with spirals and trefoils. Unfortunately, the poor preservation of the bonnet does not allow for a more accurate pattern reconstruction. The goldwork embroidery consists of normal couching of two parallel threads with a silken couching thread. The goldthread (width 0.25 mm) consists of a 0.3 mm wide silver-gilt strip spun (S-direction) around a silken core. Grave J 59 contained a bonnet made of silk on which a repeat pattern of simple five-petal flowers in a circular frame (c. 3.6 cm high) was stitched. The areas between the circles are also filled with a kind of abstract wavy thingy :). Again, the goldthreads are couched down in pairs with 35-40 threads per centimetre. Two different goldthreads are used in this design: 0.25 mm width (0.25 mm wide silver-gilt strip around silk core) and 0.4 mm width (0.4 mm wide silver-gilt strip around red silken core). There is also a strip of bead embroidery on this bonnet. The beads are 2-3 mm in diameter and are made of gilt silver foil. The beading design could not be confidently reconstructed. Although the remains of the bonnet from Grave J 63 are poorly preserved, they do show that the goldwork embroidery is worked in underside couching. The publication does contain Ingeborg Petrascheck-Heim's reconstructed of the pattern. For the embroidery, two parallel threads are couched with a single stitch. The couching thread itself has not survived (probably thus linen) but the characteristic loops of goldthread at the back of the silk twill fabric unmistakably point to underside couching. The silver-gilt thread has a width of only 0.15 mm. The goldwork embroidery on the fragments of the bonnet in Grave J 105 is of very high quality. Unfortunately, the fabric has hardly survived but points to some sort of canvas. The embroidery design included roses in a circular frame, spirals, trefoils and acanthus leaves. Unfortunately, it cannot be confidently reconstructed. The goldthreads have a width of 0.15 mm and were couched down in pairs with silk. There are 45-50 threads per centimetre. The author assumes that, because of the higher quality of the embroidery, the bonnets in graves J 63 and J 105 (and probably J 57 too) were made by professionals. Bonnet 59 might have been worked by the wearer herself or someone else in her household. Where did these professional bonnets or the raw materials come from? Either complete bonnets were imported from beyond the Alps or raw materials were imported from beyond the Alps and fashioned into bonnets by local craftspeople. Certain characteristics of the (design of the) goldwork embroidery and the used fabrics point to a date around the middle or in the third quarter of the 13th century (AD 1250-1275). Although I concentrated on the goldwork embroidery, the complete headdresses of these women also included tablet-woven bands which include goldthreads and very fine veils made of silk. All this luxury points to a wealthy population that buried their dead in the burial ground of Villach-Judendorf. As the name "Judendorf" implies, some of these people might have been Jews.

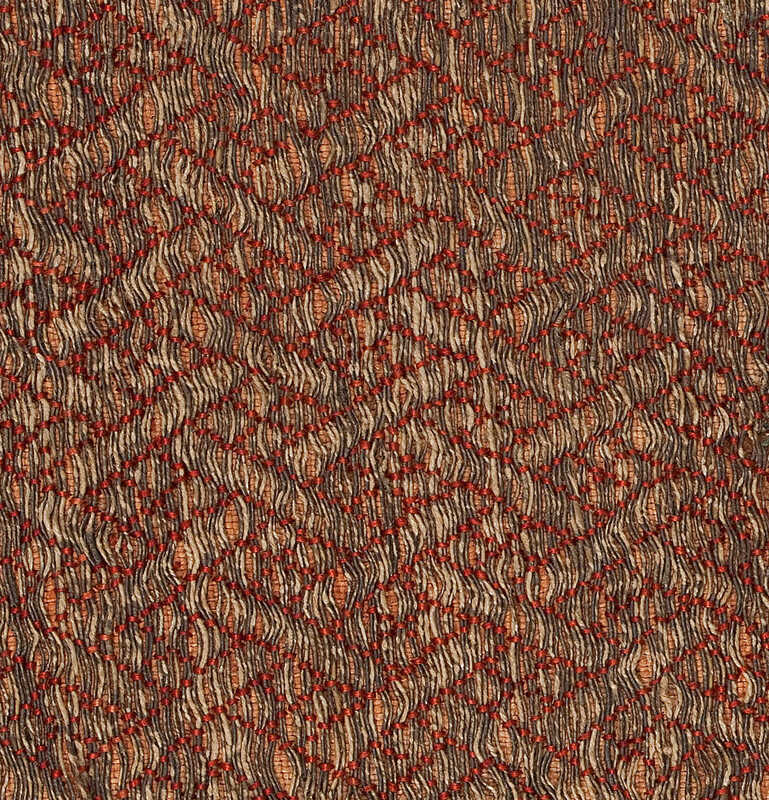

If you are interested in non-ecclesiastical medieval goldwork embroidery, you should consider buying the publication from Ingeborg Petrascheck-Heim. It contains a full catalogue of all the gold bonnets (they have woven ones too) and 101 pictures and illustrations of the finds. You can order a copy by writing an email to Stadtmuseum Villach. The book costs only € 11 + shipping. Literature Petrascheck-Heim, I., 1970. Die Goldhauben und Textilien der hochmittelalterlichen Gräber von Villach-Judendorf, Neues aus Alt-Villach (= 7. Jahrbuch des Stadtmuseums), p. 56-190. Last week's simple experiments told me a lot about the anatomy of the modern gold threads we use in our embroideries. But how does this compare to the gold threads that were being used in the medieval period? When you are familiar with goldwork embroidery, you probably know that there is a myriad of different gold threads available nowadays. This plethora of forms and shapes is a relatively new invention. Before the end of the Middle Ages, your stash would have looked rather clear and orderly. If, for instance, you lived in England, France or the Low Countries, your threads were probably made of a gilded silver foil wrapped around a silken core. However, if you lived in Germany, your thread was probably made of a strip of gilded silver glued onto a membrane (animal gut) and wrapped around a linen core. Membrane threads (usually with a silken core) were also used in the weaving of luxurious silk fabrics. But probably not in embroideries in England, France and the Low Countries. Sorry for the use of the word "probably" so frequently. Unfortunately, the makeup of the metal threads used in medieval embroideries is not routinely stated in the literature. And researchers that analyse metal threads do usually not differentiate between thread samples taken from an embroidery and those taken from a woven textile. However, I have a gut feeling that there might be a difference. After all, the technique and motions are quite different. And whilst you can use many threads for both embroidery and weaving, some work much better than others. I do not have many answers yet, as I am currently in the process of untangling the gold threads from the published data. What I can say is that the twist of the foil around the core in these medieval passing threads seems to be S-twisted. This is also the case in the modern passing threads I took apart last week. However, seeing the passing thread under the digital microscope made me realise that the width of the metal foil is very small (especially when compared to the Japanese threads). How does this compare to medieval gold threads? The number of wrappings per centimetre is hardly ever stated :(. When you look at the close-up of ABM 2107f held at the Catharijne Convent, at first glance, it does seem to correspond well with the modern passing thread. However, if you zoom in and measure the ratio of the width of the gold thread and the width of the gold foil, the gold foil is about twice as wide as the width of the thread. For the modern passing thread, this ratio is about 1:1. This means that the strips of gold foil in a modern passing thread are thinner and that there are more wraps per centimetre. Is this difference important? Does it make for a different embroidery experience? And how will we ever be able to tell? What also struck me during the second run of my medieval goldwork course was that we use modern passing threads on the two samples that were originally stitched with membrane gold. It works, but would the use of a modern Japanese thread be closer to the medieval membrane thread? Is the paper substrate comparable with the animal gut substrate when it comes to the behaviour of the thread? How heavily gilded were the original medieval membrane threads? Do they compare better with non-tarnish Japanese threads or with the real deal in which a high gold content is used? And what about the core? There are some membrane threads used in medieval embroidery that do have a silken core. But the majority is linen. And from the pictures above you can tell that the modern Japanese threads are Z-spun, whereas the historical sample (ABM t2007) on the right is S-spun. How does this affect the embroidery experience? I am definitely going to do some experiments before the start of the third run of my course.

Please do leave a comment below as I very much welcome your input on this! Literature Járó, M., 1990. Gold embroidery and fabrics in Europe: XI-XIV Centuries. Gold Bulletin 23 (2), 40–57. And references cited in this paper. Karatzani, A., Rehren, T., Zhiyong, L., 2009. The metal threads from the silk garments of the Famen temple. Restaurierung und Archäologie 2, 99–109. One of the hardest things in recreating medieval goldwork embroidery is finding embroidery materials that are similar to those used in the past. Although the composition of the gold threads used is not routinely stated in publications and museum catalogues, generally speaking, modern threads contain less real gold or even none at all. But what else can be learned from having a closer look at them? Out come the digital microscope and some matches. Although I have quite a collection of gold threads, I am going to take apart a few key ones that you are probably familiar with too: - imitation Japanese thread (#8 from Golden Threads) - passing thread (Stech 120/130 from M. Maurer) - "real" gold passing thread (Stech 120/130 Echt Gold with silken core from M. Maurer) - pure goldthread (vintage Japanese from Hauser Gallery) All these threads have a thin foil that's wrapped around a textile core thread. Let's start by having a look at how the foil has been wrapped around the core thread. Interestingly, you can see the core thread between the foil wraps in all specimens. The glare of the gold is such that we don't see this with the naked eye. If you click through the above picture gallery, you will see that the two Japanese threads are Z-spun and the two passing threads are S-spun. You'll also see that the width of the foil is much greater for the Japanese threads than for the passing threads. This probably explains why you don't have pesky pieces of foil standing up in tight turns when you are using passing thread. The changes of you "folding" a single wrap in a turn is less. It is more likely that you'll push two wraps a little apart with your couching thread. To quantify things a bit: there are c. 13 wraps/cm for the imitation Jap, c. 16.5/cm for the pure gold thread and c. 64 wraps/cm for both passing threads. Let's unwrap the foil from the core and see what it's actually made of. This exercise reveals the biggest difference between the Japanese threads and the Stech. You can clearly see in the pictures above that both Japanese threads have a golden foil on the outside of the strips and a substrate on the inside. It is white in the imitation Jap and brownish in the real gold thread. The latter is very likely a special high-quality paper, but the white stuff might be an artificial membrane. The foil of the Stech looks very differently and behaves very differently: it really is a strip of metal without another material. It stretches considerably upon unwrapping. In the pictures, you can see that the foil has a silver colour on one side and a golden colour on the other. According to the manufacturer, the normal Stech consists of a silvered copper thread which is then very thinly gilded on one side. The Stech Echt Gold is a pure silver thread that is then gilded with pure gold on one side resulting in a higher karate. Above, you see pictures of the cores of the different gold theads. All are yellow, except for the vintage pure gold thread which has a more reddish hue. To determine if they are made of real silk or polyester, I have burnt them by holding them in a flame with tweezers. The core of the imitation Japanese thread burnt with a small flame and the smell was one of something being burnt. The core of the Stech burnt with angry sparks and there was no smell at all. The core of the Stech Echt Gold burnt very quickly with a faint smell of something being burnt. The core of the Pure Gold thread burnt very quickly, but I could not detect a smell. The results hint at the core of the imitation Jap being cotton, the core of the Stech being artificial and the cores of the Stech Echt Gold and the Pure Gold thread being silk.

How do these results compare to the gold threads that were being used in medieval embroidery? Find out in next week's blog post! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed