|

Today starts the last week of my 10-week Medieval Goldwork Course. It has been an exciting journey for all who participated! And although I will need to tweak some bits of the course, it is my pleasure to announce that the course will run again from 6-9-2021 till 13-11-2021. Sign-up will be Tuesday 1st of June 19:00h CET. This leaves me with enough time to order in materials and send them out to the participants in time. And between now and the 6th of September, I will be re-filming parts of the course with new materials, update the hand-outs and conduct a few experiments in my search for materials that come as close as possible to the medieval originals. First up is underside couching. Very little has been written on the exact materials being used in this Opus anglicanum goldwork technique. Somewhere in late summer, Tanya Bentham's book on Opus anglicanum will be out and I can't wait to see what exact materials she uses for successful underside couching. In the meantime, join me in my own experiments! When you see people recreate pieces of underside couching, they often work directly on a linen background. However, a lot of Opus anglicanum was worked on a silken twill fabric backed by linen (see for instance the famous Jesse Cope). When you look at the detailed pictures of the Jesse Cope, it becomes clear that the silk twill used is of a heavier variety. But how heavy is heavy? Whilst silk twill is readily available in many colours today, getting your hands on a heavier version isn't so easy. And although the course sample of underside couching worked on a flimsy version of silk twill does work, I would love to see what results can be got by using a heavier silk twill fabric. I will therefore compare four weights of silk twill in my experiment.

So, I dressed my slate frame with a natural 40ct linen. On the linen, I appliqued the four squares of silk twill. Normally, I would use polyester buttonhole thread to set up my slate frame. But as there was no polyester thread in the Middle Ages, I decided to have a go with linen thread. I used Goldschild Nm 40/3 to attach my embroidery linen to the twill tape. That worked very well and the thread was strong enough. The big advantage of using linen thread over polyester thread is that the linen thread is rougher and thus keeping tension on your stitches is much easier. I also used the same thread to stitch on the twill tape onto the sides. However, the thread broke as it could not withstand the high tension. Switching to a stronger linen thread (Goldschild Nm 11/3) brought the solution. Now that my frame is all set up, I can start the actual experiment. I will test several materials: silk twill weight, linen couching thread and gold thread. Although underside couching with the Goldschild Nm 40/3 works, I want to try a two-ply linen thread (the Goldschild thread is a three-ply thread). The original Opus Anglicanum embroideries were, however, worked with a two-ply linen thread. But again, getting your hands on a good two-ply linen thread is more difficult. What I have been able to get my hands on is real goldthread. Not gilt, but real gold. Not with a polyester core, but with a real silk core. This goldthread comes much closer to some of the goldthreads used in the medieval period (the others were made with animal gut as a substrate for very thin strips of gilded silver; unfortunately, no one can recreate these today). Next week, I'll update you on how my first experiments went!

19 Comments

From the historical sources, we know that Utrecht and Amsterdam were important production centres of late-medieval goldwork embroidery in the Netherlands. The embroideries have survived in museum collections all over the world. But can we also identify embroidery production centres in the archaeological record? What would an archaeologist find if they would excavate your embroidery workspace 500-years from now? Would these archaeologists, by then living in a completely different world, understand that those rusty bits of metal were once your prized DOVO-scissors and your expensive hand-made Japanese needles? Luckily for them, you were probably active on Social Media :). But since there were no Social Media 500-years ago, what have archaeologists found that could have belonged to an embroidery master such as Jacob van Malborch? He was the chief embroiderer of a large embroidery workshop in Utrecht between AD 1500 and AD 1525. Thimbles! Yes, I know: 1) not all embroiderers use them and 2) other textile workers used them too. But they are pretty, fascinating and have survived in abundance. Let's explore them!

You are forgiven for thinking that a thimble is a thimble is a thimble. Nope. They are high-tech finger protectors. Their English name "thimble" sounds a bit like "thumb". And indeed, thimbles were probably first used for heavy-duty sewing through leather. You would push with your strongest digit: your thumb. Consequently, you would wear protection on your thumb. Not necessarily against pricking yourself, but more to protect your flesh from the strain of the pressure. That protection was likely a scrap of thick leather, but other materials such as wood, stone or bone were a good choice too. Would we recognise these make-shift proto-thimbles in the archaeological record? Probably not.

Real thimbles arrived in Europe in the 10th-century. They were brought to Europe through the spread of Islam and can be found in the archaeological record of the Iberian peninsula and the Balkan. Thimbles don't walk fast. It takes them several hundreds of years to conquer the rest of Europe. But from the 13th-century onwards they start to spread faster and faster. And although fine sewing and embroidery needles do not survive in the archaeological record, it is likely that these thimbles were the answer to bleeding fingers resulting from the use of metal needles.

These oldest thimbles produced in Europe were made of bronze and were cast. They are quite heavy with thick walls. They are tall, have a pointy shape and are hand punched or drilled on their sides. The top has no punches or is even open. This means that the sides, and not the top, of the thimble, were used to push the needle. Probably to save raw material, thimbles are hammered from a sheet of bronze or copper alloy from the late 14th- or 15th-century onwards. Slowly and by repeatedly heating the material, a thimble shape is achieved. You can recognize these thimbles by the characteristic folds they display at their base (see thimble above).

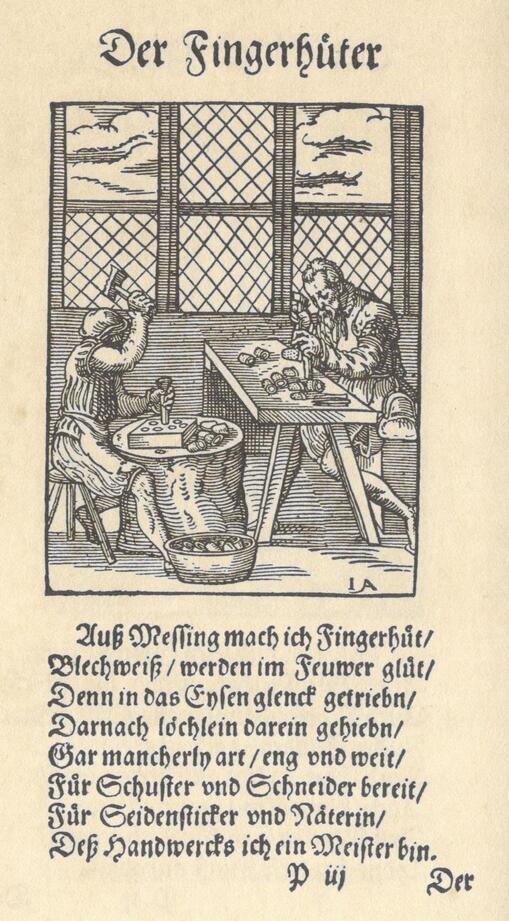

The next invention happens in Nuremberg, Germany. They invent a better way to make brass. Their type of brass is more elastic and easier to work with. Instead of hammering the thimble into shape, they start to press them into shape using increasingly smaller moulds (see picture above; the silk embroiderer is explicitly named as the receiver of these thimbles). These thimbles are of better quality. Nuremberg tried to protect their invention and people who knew the secret were prevented from leaving the town. It worked for a while and Nuremberg was the world-capital of thimble production in the 16th-century. But the guild tried to protect workers by forbidding inventions that made the slow hand-punching quicker. Once the secret of the composition of the brass was out, other places started to mechanise the punching process and took over production. But by then, the Middle Ages are over.

We know some of these "Fingerhütter" (makers of Fingerhüte=fingerhats=thimbles) by name thanks to the admission books of the Nürnberger 12-Brüderstiftungen. These were two almshouses for old men in Nuremberg. Each new brother was depicted whilst executing his profession. Sometimes interesting "gossip" about the particular brother is written down too. The oldest brother was depicted before AD 1414 and we see him drill holes into the thimbles. On his workbench, you see both closed thimbles and sewing rings. The next brother is Veit Schuster who died in AD 1592. We see him press the brass sheet in the mould. Wolf Laim (AD 1549-1621), Martin Winderlein (AD 1557-1627) and Nikolaus Zeitenberger (AD 1596-1667) are all punching their thimbles. The admission books also reveal that Martin was a quarrelsome man who could not be pacified with either food or drink. And Nikolaus did not die in the almshouse as he had become too much of a burden by being filthy and careless. Probably the result of dementia.

Literature Langendijk, C.A. & H.F. Boon, 1999. Vingerhoeden en naairingen uit de Amsterdamse bodem. Amsterdam, AWN. Mills, N., 2003. Medieval artefacts. Essex, Greenlight Publishing. Klomp, M., 2011. Metalen voorwerpen. In: M. Bartels (ed), Steden in Scherven. Zwolle, SPA.

I've uploaded a short video in which I model the different thimbles. Don't mind my hands. They suffer badly from all the anti-bacterial gels and the countless handwashing. No matter the amount of pampering :).

Let's explore last week's rationale a bit more. This rare medieval vestment is modelled on the ephod of the Jewish high-priest. Chapter 28 of the bible book Exodus described the garments that need to be made by skilled craftsmen for Aaron and his sons in great detail. Verses 6-14 tell us about the design of the ephod: "And they shall make the ephod of gold, and violet, and purple, and scarlet twice dyed, and fine twisted linen, embroidered with divers colours. It shall have the two edges joined in the top on both sides, that they may be closed together. The very workmanship also and all the variety of the work shall be of gold, and violet, and purple, and scarlet twice dyed, and fine twisted linen. And thou shalt take two onyx stones, and shalt grave on them the names of the children of Israel: Six names on one stone, and the other six on the other, according to the order of their birth. With the work of an engraver and the graving of a jeweller, thou shalt engrave them with the names of the children of Israel, set in gold and compassed about: And thou shalt put them in both sides of the ephod, a memorial for the children of Israel. And Aaron shall bear their names before the Lord upon both shoulders, for a remembrance. Thou shalt make also hooks of gold. And two little chains of the purest gold linked one to another, which thou shalt put into the hooks." (Douay-Rheims Bible which is closest to the Vulgate Latin version widely used in medieval Europe). The text makes clear that the ephod was a very precious garment with gold, gemstones and costly dye-stuffs. And it also explains the shape of the medieval rationale with the two patches on the shoulders. The name "rationale" is derived from the translation of the priest's ephod (Hebrew), to logion (Greek) into rationale (vulgate Latin) (Miller 2014, 64). Who was allowed to wear a rationale? Bishops were allowed to wear the rationale over the chasuble. Although it seems that this special vestment was sometimes granted by the pope to a particular bishop (Pope Agapetus II apparently granted one to the see of Halberstadt, Germany, before AD 984) other bishops simply copied its use. It became fashionable in the 11th- and 12th- century in Germany and then spread to France and England in the 13th-century. Curiously, Italian bishops, with the exception of the sees of Aquileia and Monreale, do not seem to have been keen on wearing it (Miller 2014, 65-66). Presently, only the bishops of Eichstätt and Paderborn (Germany), Toul-Nancy (France) and Krakow (Poland) wear this medieval vestment on special occasions. The rationale from Bamberg belongs to the so-called Kaisergewänder (held at the Diözesanmuseum Bamberg) and was made between AD 1007 and 1024 in the realm of Holy Roman Emperor Henry II. The embroidery is made with very fine, near-pure goldthreads in normal couching on dark-blue silk samite imported from the Byzantine Empire. Although presently the embroidery is applied to a bell-chasuble made of blue Italian silk damask from AD 1450, the original embroidery was also part of a bell-chasuble rather than a separate vestment such as the Regensburger rationale. The embroidery depicts scenes from the Apocalypse, an allegory of the church and busts of the apostles (Kohwagner-Nikolai 2020, 190-196). The rationale from Regensburg (part of the Regensburger Domschatz) was made in AD 1314/1325, possibly in Regensburg (Germany). It was made at the behest of king, and later Holy Roman Emperor, Louis IV, called the Bavarian (AD 1282-1347). He gifted it to bishop Nikolaus von Ybbs (AD 1270/1280-1340), bishop of Regensburg. It is made of linen embroidered with very fine gold- and silver threads as well as silks. On the front, we see an allegorical depiction of the church. On the back, we see Christ in the mandorla surrounded by angels, symbols of the evangelists and the agnus dei. The elongated slips on the front and the back contain the busts of the apostles. The two shields on the shoulders contain female allegories of Psalm 85:10. Each depiction can be identified by stitched texts in either Latin or German (Kohwagner-Nikolai 2020, 237-240).

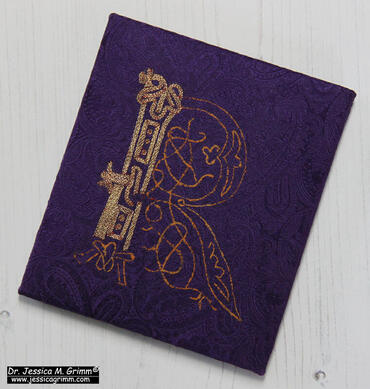

For a detailed description of the embroidery techniques and materials used for both rationale, we will have to wait for the publication of the research project results of the "Kaisergewänder", later this year. Literature Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2020. Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner. Miller, M.C., 2014. Clothing the clergy. Cornell University Press. As Germany stumbles out of the lockdown we have been in since December, I and my husband took the opportunity to visit the exhibition of the "Kaisergewänder" in the Diocesan Museum Bamberg. Although I visited this museum before, this time the latest research results on the goldwork embroidery were on display. Luckily, my husband was so kind to come on a 660 km round trip with me (promising him cake always works!). If you would like to visit this exhibition yourself, you will have to do so before the end of the month or before the rate of infections rises above the threshold again. You will need to make an appointment through the museum website and fill out a form. So, what new things did we see? First of all, I was really impressed with the amount of information now available for each vestment on display. The original captions were VERY short and that was a major disappointment on my first visit. Secondly, there was a whole room devoted to the "raw data" of the research project. This will probably all become available in the three monographs I have on pre-order. Looking at the tracings and other study results, many of my own assumptions were confirmed. And I learned so much more about these goldwork embroideries that you just cannot see with the naked eye or learn from the pictures I took and enlarged on my computer. A rather interesting piece on display was a copy of the Regensburger rationale. This is a special vestment awarded by the pope to some bishops and was modelled on the ephod of the Jewish high-priest. It is hardly being worn today. The original was stitched in AD 1314-1325, probably in Regensburg. The copy was made for Bishop Franz Wilhelm von Wartenberg (AD 1649-1661) and is now held at the Bayrische Nationalmuseum in Munich (T 178). The copy was likely made to be used by the bishop to spare the original. As you can see, the stitching on the original rationale is made with much finer goldthreads than that on the copy. And now the stalking :). As always, I take many pictures, when allowed. At some point, two women sneaked up to me as they were curious to know who this lady-with-a-Canon-stuck-to-her-face is. It turned out that I knew one of them, Dr Ludmila Kvapilová, scientific associate of the museum (recognising people with a facemask is an art I have not yet mastered). The other lady turned out to be the new head of the museum: Carola Schmidt. Carola trained as a technical weaver before studying art history. The three of us had a lovely conversation and at some point, I mentioned that I had stitched a small sample based on the lettering seen on the Sternenmantel for the conference "Über Stoff und Stein" (you can find my blog on this reconstruction here). They asked if they could display the sample as part of the exhibition. Sure! So, today I mounted the sample and send it to them. This way they can also use it as a teaching aid. I am looking forward to staying in touch with them and to sharing my expertise.

If you would like to learn to professionally mount your finished embroidery, you can find downloadable instructions in either English or German in my webshop. For my research into late-medieval goldwork embroidery, I sometimes stumble upon interesting papers that were published a long time ago. They are usually written in Dutch, German or French and thus probably inaccessible to most of you. Today, I am going to introduce the story of embroidery master Peter Joosten from Amsterdam who accepted an order for an embroidered chasuble cross for the St. Walburgskerk (St Walburg Church) in Zutphen, the Netherlands. Not everything went as smoothly as the churchwardens had hoped as master Joosten turned out to be quite a character. Unfortunately, the actual embroidery has not survived. The story starts on the feast of Corpus Christi in AD 1544 when churchwarden Coenraad Slindewater and his brother receive master Joosten and his son. They discuss the possibility of master Joosten making a golden chasuble cross for a new chasuble for the Walburgskerk. The churchwarden pays for bed and board of master Joosten and his son at Evert Meijerijnck's house and for their travel expenses from Amsterdam to Zutphen. The church accounts also list expenses for the linen embroidery cloth and its shipping to Amsterdam and expenses for the design drawings. The payment for the later is made to glazier Johan Yseren. This is not unusual as embroidery patterns are more often made by glaziers (Van den Hoven van Genderen 2015) who needed to be able to paint in order to make leaded church windows. Master Joosten and his son travel to Zutphen again on the last day of February AD 1545 to sign the work contract. All expenses are paid for by the churchwarden. Master Joosten and his son even receive money for the loss of earnings whilst travelling. The contract stipulates that the churchwardens lend the embroidery pattern to master Joosten and will receive it back when the chasuble cross is finished. The embroidery should look better as both that of the cross that was shown to master Joosten by the churchwardens and better than the cross master Joosten had taken with him to show the churchwardens. Regarding the embroidery materials used: Master Joosten should only use the best materials and he should source the pearls himself (and being paid separately for them). Master Joosten demands a fee of 25 pont groit (probably the golden Carolus Guilder in use at the time). However, the churchwardens offer only 20 and the promise that the finished work will be valued upon completion. If to be found of a value more than 20 pont groit, master Joosten will receive a higher fee. It was apparently not easy for lay-people to judge the quality and value of goldwork embroidery. A stipulation like this in which the finished work is valued by a group of people is not unusual (for instance the work of Mabel of Saint Edmunds, embroideress for Henry III in London, was valued by "the better workers of the City of London" (Kent Lancaster, 1972)). The work contract also stipulates that master Joosten will finish the work as quickly as he can. He is forbidden to take on other work as long as the golden chasuble cross has not been finished. And whilst the churchwardens sign the contract with their full names, master Joosten uses a mark similar to that seen with stonemasons. It is thus likely that he was illiterate. On the 30th of July AD 1546, more than a year (!) after signing the work contract, master Joosten and his son travel to Zutphen again. They show the churchwardens part of the golden chasuble cross (the cross likely consists of several separate orphreys). Again, the churchwarden pays for travel, board and bed for both. And master Joosten goes back to Amsterdam and goes silent. It will take until the autumn of AD 1547 before a badly written letter reaches the churchwardens in which master Joosten asks for the patterns for the rest of the cross. He promises, that when he gets them in time, he will meet them at Easter to deliver the finished cross. However, Easter comes and goes and there is no chasuble cross. But the churchwardens do receive another letter in which master Joosten apologizes for the delay, but he has an abscess on his hand. He promises to meet them two weeks after Pentecost. This time, he sticks to his word. Fourteen days after Pentecost AD 1548, he brings them so many orphreys that they can make up half of the cross. The churchwardens pay him 5 pont groit for his work. And as always, all the other expenses for him and his son. Master Joosten does not speed up at all. Instead, he goes shopping. The Friday after the second Sunday of Lent in AD 1549 (!) he begs the churchwardens to pay for the oxen he has bought from Andries te Griffel. And guess what: the church wardens did pay for the oxen!

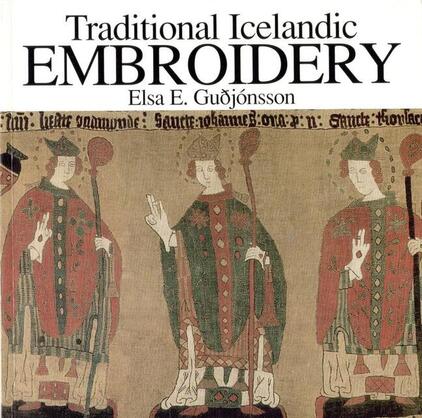

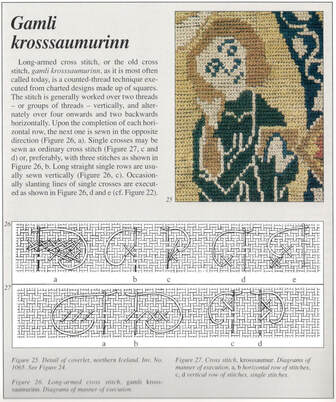

The churchwardens are finally having enough on the 25th of January AD 1550. They sent master Joosten a letter in which they threaten with the law. This helps. He and his daughter come to Zutphen and deliver the other half of the golden chasuble cross on the 14th of September AD 1550. The churchwardens, together with Johan Schymmelpenijncks (in which home the meeting takes place), Alphert van Till, Rense van Holthusen, the brother and brother-in-law of Coenraad Slindewater. These seven men appraise the work of master Joosten and decide that he shall get his 25 pont groit (minus part of the fee he had already been given in AD 1546). And again, they pay for everything for master Joosten and his daughter. In total, the chasuble cross has cost the churchwardens: I Cxxij gl. van xxviij st. br. xxij st. br. ende V placken. The author of the paper writes in a footnote that this amount "shall have been more than two-thousand guilders in today's money". According to the historical calculator on the website of the CBS, this would be the equivalent of € 25665 or $30480. No wonder the churchwardens were so lenient with master Joosten. They had invested thousands in AD 1546 and were afraid that it would all be for nougth if they pushed master Joosten over the edge. It also becomes clear that master Joosten probably violated the work contract as he must have taken on other work too. The above-mentioned fee would not have sustained him and his family over the six years it took to deliver the complete golden chasuble cross. But why he needed an oxen for his goldwork embroidery is anybody's guess :). Literature Hoven van Genderen, B. van den, 2015. Gewaden op papier. Kerkelijke textilia in Utrechtse archiefstukken. In: M. Leeflang & K. van Schooten (eds), Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden, p. 14-23. Kent Lancaster, R., 1972. Artists, Suppliers and Clerks: The Human Factors in the Art Patronage of King Henry III. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 35, p. 81–107. This title can be read online for free through JSTOR. Meinsma, K.O., 1901. Geschiedenis van een kazuifel, vervaardigd door Mr. Peter Joosten, borduurwerker te Amsterdam voor de St. Walburgskerk in Zutphen, Oud Holland 19 (2), p. 77-85. This title can be read online for free through JSTOR. Today I am going to review a lovely little book most of you would probably never have come across: Traditional Icelandic Embroidery by Elsa E. Gudjonsson written in 2006. In only 96 pages, Elsa gives an overview of Icelandic embroidery made during the past 500 years in English (!). Being a rather barren island where almost everything needs to be imported, the embroidery is of a special nature too. Whilst mainland Europe uses silks both for the threads and for the fabrics, Icelanders used wool on wool or linen. Both for ecclesiastical embroidery and for embroidery on folk dress and household items. The use of metal threads is rare. The book consists of two parts: History & Techniques and 23 pages of original patterns. The later have all been transcribed as cross-stitch patterns with a key for DMC stranded cotton. The book describes several techniques which are characteristic of Icelandic embroidery: Refilsaumur (laid and couched work), Glitsaumur & Skakkaglit (straight darning and pattern darning), Gamli krosssaumurinn (long-armed cross-stitch), Augnsaumur (eyelets), Pellsaumur (Florentine stitch or bargello), Sprang (darned net and drawn thread work) and Blomstursaumur Skattering (floral embroidery). Each technique is explained with stitch diagrams and pictures of historical pieces. I was especially surprised to find whole embroideries worked in long-armed cross-stitch after AD 1550. They remind me of the much earlier embroidered vestments now in St. Paul im Lavanttal, Austria. Interestingly, the name "Gamli krosssaumurinn" means old cross-stitch. Krosssaumur is the modern Icelandic name for cross-stitch embroidery. As for Continental Europe, modern cross-stitch does not feature in medieval embroidery. Unfortunately, very little is known about Icelandic embroidery in the Middle Ages due to a lack of surviving pieces and an absence in the written sources. Especially the latter is remarkable as there are plenty of sources describing textiles. However, the few sources that exist indicate that women were the embroiderers. There are no instances of men being named as embroiderers. Especially upper-class women and nuns were involved in the production of high-end embroideries for the church. This tradition continued after Iceland became Lutheran in AD 1550. One particularly saucy embroidery story involves Helga Sigurdardottir. She was the wife (yup, they did things a little differently in Iceland) of the last Catholic bishop of the see of Holar, Jon Arason. In AD 1526 they drew up a contract in which was stipulated that Helga would make embroideries for the church of Holar as long as she was able. She became a set income per year for her service. Helga's work must have been outstanding as she is named in a poem of AD 1594 as one of the most skilful needlework women of her day. Helga probably trained up her grand-daughter Pora Tumasdottir who became a famous church needlework woman herself. And what happened to bishop Jon? He was killed by the troops of the Danish king in AD 1550 when he revolted and refused to accept the reformation of his church. Where to find this book? I bought my copy directly from the National Museum of Iceland for about €23 + shipping. They also have a second book that might interest you: a facsimile of Icelandic pattern books from the 17th-, 18th- and 19th-centuries. However, that one is quite pricey at €180. Pictures of several pages of these original pattern books are included in the embroidery book by Elsa. I know that these books can probably be had from Amazon and the like. But please consider ordering from the National Museum directly. Museums are hit hard by the pandemic due to closure or greatly reduced numbers of visitors due to the absence of tourists. The Museum shipped my book immediately and it was here within two weeks. The ordering process is easy with a credit card and completely in English.

P.S. Virginia Sullivan won last week's giveaway and has been contacted. The cross-stitch charts are on their way to her. A thank you to all who participated! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed