|

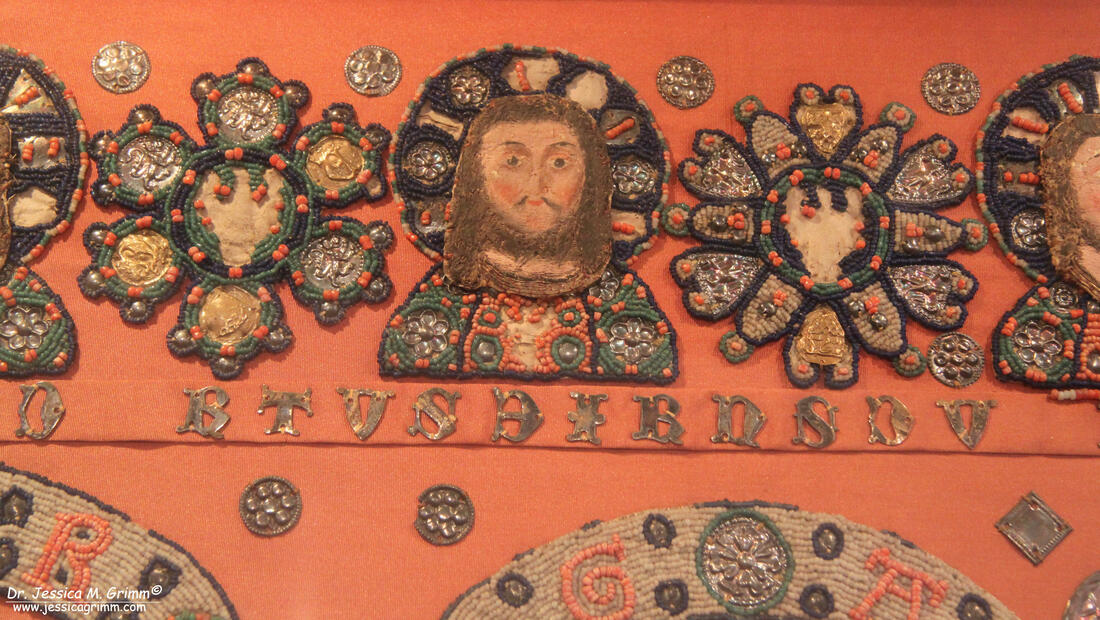

I and my husband had a most lovely trip to Cheb (German: Eger) in the Czech Republic. The local museum houses a spectacular medieval bead embroidery: the Egerer Antependium. Although the museum is closed to the general public due to renovations, Alena Koudelkova kindly agreed to show us around. Check my previous blog post if you want to read the story on how I discovered this gem of a medieval embroidery. The Egerer Antependium measures 2,18 m by 90 cm and was probably made by the Poor Clares of Cheb in the early 14th century (it is a staggering 700 years old!). There are two identical rows with ten saints. Each saint is framed by two columns topped by an arcade. For easy identification, the name of the saint is stitched into the column and the arcade. The bottom row shows (from left): John the Evangelist, James son of Zebedee, James son of Alphaeus, Margaret the Virgin, Mary of Intercession, Jesus (who blesses Mary to his left), Agnes of Rome, Saint Cecilia, Cunigunde of Luxembourg and Saint Ursula. The row above shows: the Archangel Gabriel visiting the Virgin Mary, Agatha of Sicily, Mary with the six-year-old Jesus, Clare of Assisi, Mary Queen of Heaven with baby Jesus, Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Lucy, Saint Barbara and Saint Bibiana. The columns-arcade-frames measure 35 cms in height. The figures themselves are about 28 cms in height. The iconography of this piece supports the thesis that the Poor Clares of Cheb were the embroiderers of this Antependium. For starters: it is very female heavy :). The Virgin Mary is represented four times. She is accompanied by other holy virgins (Margaret, Barbara & Catherine as well as Agnes, Lucy & Cecilia). Clare of Assisi is the founder of the Poor Clares and therefore prominently displayed in the middle of the Antependium. Agatha and Ursula often accompany Clare of Assisi. Cunigunde of Luxembourg is especially venerated in the diocese of Bamberg to which Eger belonged. Bibiana possibly refers to a local veneration or to the sponsor of this piece. Furthermore, in the lower left corner, we see John the Evangelist celebrating mass with the two Jameses as supporting diacons. Especially John the Evangelist was widely venerated by nuns in the High Middle Ages. There is a third row sitting above the previous two rows. This smaller row, a mere 16 cms in height, comprises of the busts of Mary and Jesus flanked by the twelve Apostles. It is quite possible that this row is of a later date. The busts were probably originally silk and goldwork embroideries on linen. The embroidered parts were then covered with paint (I've seen another medieval example in Vilnius, Lithuania). The busts were then cut out and placed on top of the beaded halos. Each bust is alternated with beaded floral motives. A possible later date is supported by the fact that the beads in this row a slightly darker and the metal decorations of a different type. As there are no contemporary written sources, the dating of the piece is mainly based on stylistic grounds. Several of the iconographic scenes are first seen during the mid- to late 13th century. But also the style of the figures themselves discloses the period this piece was likely made. Some of the figures are somewhat stiff and depicted frontally (the Jameses and Clare) whereas most others are depicted more life-like with garments full of movement as was the norm in the later Gothic period. The piece as a whole breathes the strict order of the older Romanesque style. Probably originally made for the chapel of the Poor Clares of Cheb, situated in the Franciscan Church of the Ascension, the Antependium did not stay there. When the Poor Clares got their own church in 1465, they probably gifted the Antependium to the St. Jodok church in Cheb where it stayed until it was transferred to the newly opened museum of Cheb in 1874. Major restorations have transformed the Antependium somewhat. The last one took place in 1928 by Sr. Virginia Erhart of the Congregation of the Holy Cross in Cheb. She worked under close supervision of the County Conservator. It took her over a year to take the beaded applications off the red silk backing from the Baroque period. All beads were cleaned and re-strung when necessary. Then the beaded applications were re-applied to a red silk backing re-enforced by linen. During an earlier restoration, the writing between the first and the second row had already been muddled up and so doesn't make sense anymore. The beaded applications consist of strung beads couched onto vellum. This is clearly seen in those places where the beads are now missing. Sometimes even glimpses of the blue design lines can be seen. The order of work likely has been that firstly those contours were couched. Then the metal decorations were applied before the whole design element was filled with more couched beads. The colour palette is quite restricted with blue, green and white beads being the main colours. Black beads are used sparingly as are the red coral beads and the real gold beads. The size of the beads is remarkably uniform and mainly seems to correspond to a modern bead-size 11. The beads of the face of the Virgin Mary with baby Jesus are real freshwater pearls. These kinds of bead embroideries are very rare. This is due to the fact that their raw material was precious and could easily be recycled. Their origin lies in the pearl embroideries from Byzantium which were made since the 6th century. The idea came to Central Europe in the 9th century through Charlemagne with his contacts to the court of Byzantium. Glass beads were produced in Venice since 1200 AD and they started to supersede the real pearls from the 13th century onwards. These beads had to be imported from Venice well into the 14th century when local production took over (especially in Bohemia, now the Czech Republic). In turn, bead embroidery was superseded by silk embroidery in the 15th century. On the one hand, while beaded embroideries where quite heavy and impractical (in effect, the Egerer Antependium consists of many small embroideries forming a larger piece) and on the other hand while the Renaissance demanded ever more realistic and life-like depictions which couldn't easily be achieved with beads. Sources:

Siegl, K. (1929): Das Egerer Antependium, Unser Egerland, pp. 80-81. Tietz- Strödel, M. (1992): Das Egerer Antependium. In: L. Schreiner (ed.), Kunst in Eger, pp. 248-258. P.S.: This research was partly sponsored by a most generous PayPal-donation of one of my dear readers. If you like what you read on this blog and you can spare some small change, please consider making a donation via the PayPal button at the top of this page!

6 Comments

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed