|

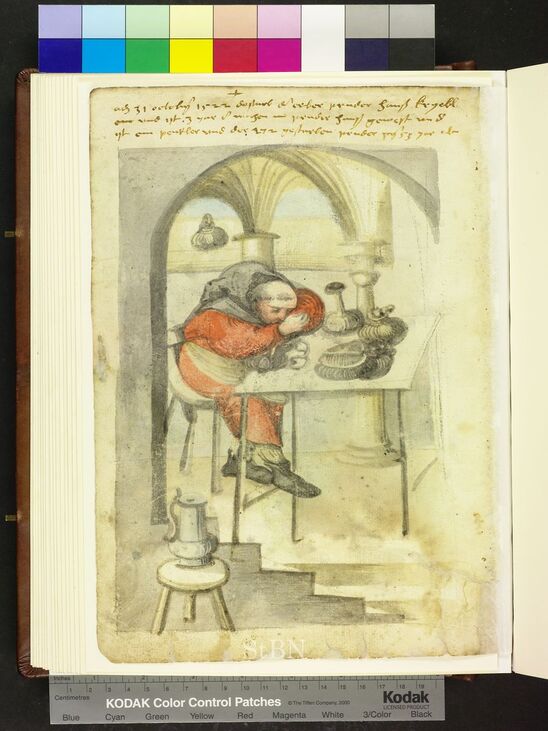

Duh! Of course, you can. After all, most of us have adequate heating and lighting in our modern homes. But what happens when that is not around? With the return of winter here in the Alps coinciding with the start of the museum season, the above question became suddenly relevant. As the climate is not very warm in Northern Europe, you do wonder if the production of high-quality goldwork orphreys was a year-round activity in the late medieval period. In addition, the amount of daylight would have been another prohibiting factor. The regulations of the embroiderers of Paris from AD 1292 expressly forbid stitching by candlelight. This is one of the reasons why I wanted to become a volunteer at the Glentleiten Open Air Museum. So let me tell you a bit more about the building I am working in, the embroidery I am working on and my clothing plans for the future. Although we are blessed with a lot of old stuff here in Europe, you will probably not find a preserved home from the 1500-1550s complete with its original furniture. Although Glentleiten has houses built in 1482, 1508 and 1555, these have all been 'dressed' according to a much later date. Remember, these were people's homes until quite recently! And naturally many updates happened during the past 500 years. So, I am using a house built in 1637/38, but with a reconstructed interior from 1700. Still at least 150 years too young, but it will need to do. The house is named after one of the families that used to live there: Zehentmaier. The 'maier' bit of the name hints at the fact that these were farmers and the building was indeed used as a farm. Today, the ground floor houses the modern pottery, the old living room (which I use) and the old kitchen (interestingly situated in the hallway). There is also an upstairs with additional small rooms. The above picture shows you the reconstructed kitchen. Cooking was done on an open fire. There is no real chimney. A fire-proof hood collects the smoke and leads it out through the attic and out into the open. Behind the modern iron gate in the middle of the picture, is the old living room (it can be closed off from the kitchen by a wooden door). You can see one of the small glazed windows at the far end. Just at the left rim of this picture is the entrance door. And there is a further entrance door on the right (not visible in this picture). The kitchen literally occupies part of the hallway and could easily be opened up by opening the doors. This undoubtedly helped with the fumes from the open fire. As you can see, it is all very basic and would probably not differ much from how many people lived in 1500-1550 (the first half of the 16th-century). Here you see a picture of the old living room. It has four small glazed windows (there is another one just outside the picture on the left). Back in the first half of the 16th-century, there would likely not have been glass. They would either have been open to the elements (with shutters) or they would have had oiled parchment as a covering. This produces a milky light. On a bright day, the light in the corner where the table stands, is fine for doing goldwork embroidery. However, what you can't see in this picture: the wall is made of wooden planks. The wooden planks have gaps... You are protected from the worst of the elements, but that is it. You cannot stitch here when the temperatures drop. And this is me, last November, in my current stitching spot: in front of the oven. When the museum knows that I am coming, they fire her up three days (!) in advance. She is not fired through the night because of the danger of fire breaking out (remember: there is no real chimney). Yesterday, the outside temperature was quite a bit lower than it was in November. When you come into the room, it feels quite nice. However, you start to cool out after about 30 minutes and you have a hard time getting warm again. By about three o'clock, you are getting comfortable again. The oven has then been burning for hours and it is about the warmest outside too. So, if you would be able to safely fire her through the night, you could embroider more comfortably. For the record: I was wearing jeans over thick tights, thick woollen socks, my walking boots, two t-shirts, a woollen Norwegian cardigan and a large woollen shawl! And underwear for those who wonder. At the moment, I am having a set of medieval replica clothes made and it will be interesting to see how they compare. By the way: I am still feeling quite stiff from having worked for a couple of hours in this quite cool environment. But then there is the small, but somewhat important issue of lighting. The above picture is taken with flash. Back in November with its gloomy light, I had to use two lamps to work and be able to show visitors what I am doing. That's how gloomy the light can be in this room. This was definitely not the spot where an embroiderer could have been working in the first half of the 16th-century. Could the embroiderer have alternated between the spot in front of the window and then walk over to the oven to warm up? Theoretically, yes. However, for good embroidery, you need to get into a rhythm. That would have been difficult as you cool out quite quickly and you tend to warm up slowly. So, what was the solution? Where and when did people embroider back in the late medieval period? There is a lovely resource that depicts retired medieval craftsman going about their business: Die Hausbücher der Nürenberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen. And although there is no medieval embroiderer depicted, there are other textile related crafts that probably give a good indication of how a contemporary embroiderer would have worked. Spoiler alert: it is going to be drafty. - Heinrich Sibenburger, the cloth shearer, entered the almshouse in 1555. Heinrich works in front of an open window. - a cloth maker who works outside. - as does the dyer. - A weaver from the early 15th-century, there is only one 'glazed' window, the rest is open and he seems bare-legged. - Another cloth shearer with small open windows in the background. - This person combs wool in a rather open workshop around 1500. - Otto is sitting outside in the late 15th-century to make cords. - Hans is clearly struggling to see the sewing on the purse he is making in the early 16th-century. - At around the same time, another Hans works his purses in the door opening. It is unfortunate that the older depictions in the Hausbücher don't show any of the architecture. Pictures from after the middle of the 16th-century show increasingly larger glazed windows. Lots of very interested visitors and the cold made for very little progress on the or nue figure of St Nicholas. Are my experiences and observations comparable to that of a medieval embroiderer? To a certain extent. My medieval counterpart was likely a man. Typically, men have more muscle tissue than women do and this wonderful stuff generates heat. That's why men in general have fewer issues with being cold than women do.

Were medieval people just made of hardier stock than me? Yup. As a Westerner born in the last quarter of the 20th-century, I have had central heating at my disposal for most of my life (with a brief interruption when I was living in England: I was cold all the time. Older night-storage heaters are a crime against humanity.). And although we do not heat excessively, but put on a cardigan instead, I do not doubt that it is much more comfortable than it was in the medieval period. Periodically, I will update you on my work in Glentleiten. It will be particularly interesting to see how my replica clothing holds up. And at what point I can actually move into the doorway or even completely outside with my stitching. Do come by to visit me if you can! You can find all the future data here. Hope to see many of you at Glentleiten this year!

12 Comments

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed