|

German medieval embroideries are often characterised by a composite thread not seen elsewhere: gold gimp. This is a relatively thick piece of string wrapped with a thin thread of membrane gold (gilt animal gut wrapped around a linen core). Was this a ready-made thread? Did the embroiderers make the thread themselves? Is it either pre-made or made during the actual embroidery? Let's see if we can find the answers! Here you see a detail of the Nativity scene from the chasuble kept at the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg. The nimbus is edged with this composite thread: gold gimp. Here's a close-up of the gold gimp. The wrapping isn't very neat. But what is more puzzling: there are no couching stitches to attach the gold gimp to the background fabric. The membrane thread isn't used to do this either. Firstly, it would be far too fragile to endure being pulled through the fabric multiple times. I've worked with recreated membrane threads, and they definitely do not hold up to this kind of abuse. Secondly, you can tell from the above picture that the membrane thread is wrapped around the thick string and does not penetrate the fabric. And what about the 'mess' on either end of the gold gimp? What's that all about? And then I remembered that Alison Cole had written about making silk gimp before it was commercially available. She describes a method whereby you make that composite thread whilst you embroider. Let's see if that works. The ratio of string to membrane gold is about 5:1. From my experiments with the recreated membrane gold, I know that it is more similar to Japanese thread than to passing thread. But it isn't the same. Its core is made of linen instead of cotton, and the spinning direction is opposite.

Trying to recreate gold gimp wasn't entirely successful. It works, but it isn't very neat. And it is very fiddly to do. Nevertheless, I did learn a few things. Firstly, it is possible to hide the couching thread completely. Especially when you use a very thin linen or silk thread for this (mine was a bit bulky). Secondly, the thick string should be as firm as possible. Cotton string worked less satisfactorily than stiff, non-squidgy linen string. And thrirdly, one should leave a tail of the gold thread at the start. This can be used to wrap the plunged string at the start. Just as I was able to do at the end. My little experiment also hints at the impossibility of producing a gold gimp as a pre-made thread. The wraps would come undone as soon as you take off tension. You would need to glue them onto the string to prevent this from happening. And I don't think there is glue in these threads. The glue would adhere to the thin membrane and tear the fragile thread apart as soon as you manipulate it to work with it. Any thoughts?

12 Comments

This blog post is taking way longer to write than I intended. Sorry, I fell down a rabbit hole. And then another one :). I will find myself in both holes in the state library in Munich on Friday. What happened? As always, I think I have seen the same embroidery before, but when I look into it more deeply, things turn out not to be as similar as I thought. When we looked at the chasuble with embroidered scenes of the Life of Mary in the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg last week, I knew it belonged to a group of similar pieces. Were they all made around the same time in the same place? Or do subtle differences hint at multiple workshops in a much wider production area? Let's have a look. Vestments with embroidered scenes from the Life of Mary contain different combinations of well-known events in Mary's life. These are usually: Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi and Circumcision. Other scenes might be the Presentation at the Temple, the Flight into Egypt, or the Dormition. To aid recognition, the scenes have been standardised. These embroideries were made in the 15th century and the early 16th century. Some embroideries are so similar that they hint at the use of block printing to transfer the design onto the embroidery linen. But how similar is similar? Above, you see three renditions of the Annunciation. In all three cases, Mary is standing behind a reading desk. However, the designs are so different that they do not stem from the same pricking or printing block. Interestingly, the majority of these embroideries omit the reading desk. This means that these three embroideries were using a similar model book that differed from the model book all the other producers of these embroideries used. Desk or no desk is thus probably a characteristic of a particular production area. But now look more closely. Let's explore the embroidery techniques used. The background consists of a diaper pattern. In all three cases: an open basket weave in red silk (faded to pink in Görlitz). The background pattern also seems to be a defining criterion. Most pieces have these sunny spirals in the background. The difference between stitching a sunny spiral (no counting) and a diaper pattern (counting) is a fundamental one and results in a very different product (taste). Therefore, I think this is region-specific and not workshop-specific (i.e. I don't believe there were 'diapers' and 'spirals' in the same region). The embroidery materials used are pretty similar for all three pieces: linen fabric, gold threads and untwisted coloured silks. However, there is also gold gimp in two pieces. This is the composite thread that goes around the nimbus and along the edges of the clothing in the above picture. The embroidery from Brixen does not have this particular thread. I think that this was a thread that embroiderers made themselves. The edges in the Brixen piece are marked with embroidery. Maybe this specific workshop did not know how to make the thread or was just not keen on working with it. Now look at the filling of the nimbus. The pieces from Magdeburg and Görlitz show Italian couching (laid silk with a gold thread on top). A couple of months ago, I wrote a tutorial on this technique. The piece from Brixen shows a very different filling: a sunny spiral. Is this workshop specific due to the preference of the embroiderer, or is this due to local taste?

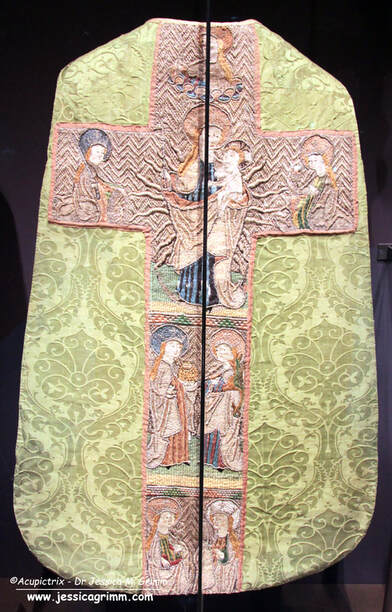

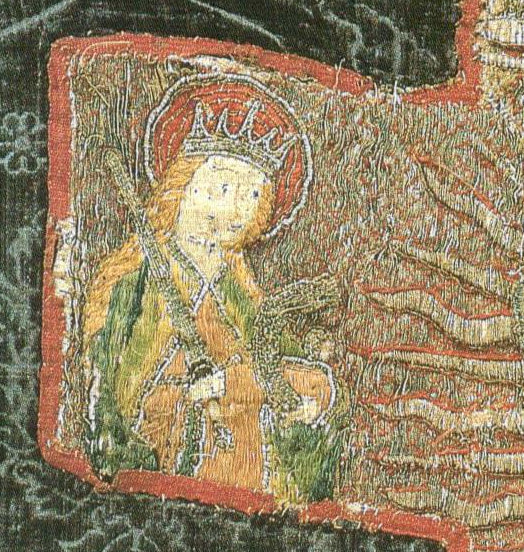

One thing that I think is workshop-specific is the border between the orphreys. This would be a perfect way for an embroiderer or an embroidery workshop to put their stamp onto their work. The borders consist of simple basket weave over string padding in all three cases. The border from Görlitz shows these very fancy triangles in silk and gold thread. If you would like to recreate it, have a look at the tutorial I made. I am collating all related pieces on a Padlet. With a bit of luck, groups will begin to form, and two or more pieces might come from the same workshop. In the future, art historians might be able to locate these groups in a specific region. My Journeyman and Master Patrons have access to this fascinating ongoing research. Before we dive into a new medieval embroidery topic, I must let you know that I had to postpone the sign-up date for the Medieval Goldwork Course. The production of the real gold threads has been delayed, and they won't be here on time. Due to various teaching commitments and the required travelling, the new sign-up date will be September 3rd 2024. I apologise for the delay! In the meantime, I am updating the course contents with lots of additional pieces, pictures, downloadable literature, and whatnot. This version will be the most comprehensive so far, offering even more in-depth knowledge. And as always, past students will have access to the updated course contents! Last week, Sabine Ullrich, curator of the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg, invited me to view a chasuble cross in storage. To my delight, Sabine came up with a few additional pieces for me to study. While there are currently no medieval embroideries on display in the museum, textile enthusiasts should visit as there are beautiful late-medieval and 16th-century tapestries on permanent display. The original chasuble cross I came for belongs to a group of German goldwork embroideries that depict the life of Mary. The scenes are standardised, not unlike the Virgo inter Virgines embroideries I told you about in an earlier blog post. The chasuble cross was made somewhere in the middle of the 15th century. Let's explore! Here you see the chasuble cross in question. It is kept under glass in a frame and thus difficult to photograph. Getting it out there requires a textile conservator and might damage the embroidery. It is not worth the risk and is unnecessary for my research. From the top, the cross shows the Nativity in the centre (according to the Revelation of St Bridget), with the Adoration of the Magi on the left and the donkey and the oxen on the right. Below is the Annunciation, followed by the Visitation at the bottom. The chasuble cross had been mounted onto a chasuble (also kept in the museum), and there is no corresponding column for the front with possible additional scenes. When you look at the damaged areas in the faces and the mantles of Mary and Elisabeth, you see that the whole embroidery is executed on two layers of linen. A course linen on the back and a fine linen on which the design was drawn or block printed. The gold threads are of the membrane type (probably with a linen core) and have completely oxidised to black. This embroidery once looked very different! Whilst the blues and the greens are still quite vivid, the orange has probably faded a lot. The silk embroidery on the clothing is of the very regular encroaching gobelin stitch type. The faces were originally stitched in tiny split stitches that followed the flow of the facial features. Just like in Opus anglicanum. Mary's long, flowing hair is a much messier affair. I think these are longer split stitches mixed with straight stitches. Parts of the clothing of Mary and Elisabeth are worked in pairs of couched gold thread. The couching pattern is a simple bricking pattern with a light-coloured silken thread. The folds are accentuated by string padding. The string padding is made of linen threads twisted together. The edges are embellished with a gold gimp. A gold gimp is in this case a linen thread wrapped with a thin gold thread (membrane gold). This gold thread is thinner than the gold thread used for the rest of the gold embroidery. To create the edge of the halos, two gold gimps have been twisted together and couched in place.

The filling of the halos, the bit of blue sky and the grassy area the women are standing on have been embroidered in a technique that's often called Italian couching. The area is first filled with laidwork in coloured silk. The silk is further fixated by couching down a single (or double) gold thread on top. The gold threads are spaced so that the silken laidwork is visible. In order to minimise waste, the gold threads are not ended/plunged at the end of a row. They are just hidden close to the edge of the design element. I have written a tutorial about this trick. The architectural background is rather sparse. There's a simple vault over the women with keystones shaped like flowers. Again, padding has been achieved with those linen strings. The diaper pattern in the background is an open basket weave made with red silk. It is one of the most popular diaper patterns ever used. The borders between the different orphreys have been embellished with simple basket weave over string padding. Either with gold threads only or with a combination of gold threads and coloured silks. Next week, I will show you further examples of this iconography. Let's see if we can find clusters within the larger group. Further down the road, we will also see if the gold gimp can be recreated with modern materials. My Journeyman and Master Patreons can find more detailed pictures of the chasuble cross on my Patreon page. Their generous monthly contributions made my travels to Magdeburg possible. Thank you very much! Professional embroidery is very different from hobby embroidery. Sometimes, hobbyists remark that the back of my embroidery isn't very neat. For some, a neat back is the hallmark of excellent embroidery. It makes sense to have a neat back when the embroidery can be viewed from both sides. But when that's not the case, there is no need for an overly neat back. Medieval embroiderers knew that. As they were professional embroiderers trying to make a living, speed was of the essence. A neat back was not. And whilst there were different qualities of embroidery for different purses, cutting corners can be seen in many pieces. By no means only in lower quality embroidery. The grapes on the Anne Geddes chasuble from Mainz are a case in point. You will find a downloadable PDF of the below instructions on my Patreon site. You can make your grapes any size you like. Mine are 1,5 cm in diameter. You can also make as large a bundle as you want. Start by padding your grapes with three layers of satin stitches. I've used soft cotton for this. Make sure your last layer runs horizontally and just within the design line of the grapes. Modern embroiderers would now probably proceed by shading each grape individually. Not so our medieval embroiderer: he did the whole lot in one go! Add shaded satin stitch or laid work on top of the padding. I've used a slightly twisted silk by DeVere Yarns (#60) in three shades of blue. Once all the silk is in, add a few highlights with your gold thread. I've used a #6 passing thread directly in the needle. Add the outline of the grapes with a dark blue silk in split stitch. Feel with your fingers where the padding is. You can also easily peek between the silken stitches to see where you will need to go. These split stitches couch the silk and the gold thread down and define the grapes. And that's all there is to these super simple, yet highly effective padded grapes. As always, my Journeyman and Master Patrons find a downloadable PDF with the instructions on the Patreon website.

When I reviewed the 'Art of Gold Embroidery' a few weeks ago, the book's biggest drawback is that it is mainly written in Uzbek and Russian, languages most of us are unfamiliar with. It also seems to be impossible to get hold of. Several people asked me if 'The art of gold embroidery in Uzbekistan' by Suzanne Pennell would be a good alternative. As this was also the primary source used by Dr Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood in her chapter on Uzbek gold embroidery in the 'Encyclopedia of Embroidery from Central Asia, the Iranian Plateau and the Indian Subcontinent', I decided to order a copy and review it for you. Suzanne Pennell wrote the book almost 25 years ago. It is her master's thesis submitted to the James Cook University in Australia. Various online bookstores offer the book as 'print on demand'. This means that the book looks like you have printed it on your home office printer. The many pictures in the book are of sufficient quality to accompany the text. However, you would be disappointed if you hoped to drool over detailed images of the beautiful goldwork embroidery. Also, keep in mind that this is a MA thesis. It was written by someone who relied entirely on translators to do her field research in Uzbekistan, as she could not speak Uzbek or Russian. That being said, it is the only book available in English which summarises the extant Russian literature on the topic. The book starts with a short introduction and the research methods employed. Pennell interviewed the embroidery master Bakshillo Jumeyev (writer of the 'Art of Gold Embroidery', a mother and daughter preparing a trousseau, visited museums in Tashkent and Bukhara and ploughed through the literature. The first chapter gives a broad overview of the history of the area of Uzbekistan and the archaeological and historical evidence for gold embroidery. As noted before, the evidence is scant, primary literature resources are absent, and references in classical Greek literature are not critically reviewed. This would be an excellent research topic for an embroiderer fluent in Uzbek, Russian and preferably Chinese. The second chapter I liked best. It talks about the materials and tools used and the organisation of the embroidery guild. To me, this is an ethnographical study that compliments my research on medieval goldwork embroiderers. It fleshes out the scant information I have and paints a picture of how the lives of medieval gold embroiderers might have been. It also makes you realise how little we know. For instance, every diaper pattern likely had a name. It makes communication within the embroidery workshop and between the workshop and the client a lot easier when techniques and textures have names.

I found the rest of the book also extremely interesting! Pennell aimed to document and explain the changes goldwork embroidery in Uzbekistan had undergone when regimes changed from Emir to Russian Tsar to Communist Russia to independence in 1991. A whole chapter is dedicated to detailing the practice at the last courts of the emirs. Opulence and self-indulgence led to a Golden Age for Bukhara's gold embroidery. At first, not much changed when Tsarist Russia colonised the area. However, everything changed after the October Revolution in 1917, especially as Bolshevik ideology required women to emancipate and join the workforce. Gold embroidery changed from a predominantly male occupation into a female occupation under state control. After Independence in 1991, the Uzbek government actively promotes goldwork embroidery to forge a new national identity. Reading Pennell's MA thesis, I better understood why the Uzbek government pours so many resources into organising a biannual International Gold Embroidery Festival. Such festivals hail back to the days of the emirs when fairs like these were held several times a year to display the products and skills of all the master embroiderers and their workshops. And remember the gold embroidered coat every participant got? That's an ancient custom, too. Gifting 'robes of honour' to important guests was quite the norm. All in all, I really liked the book, especially because I can use its contents to help me understand the pictures and texts in the 'Art of Gold Embroidery'. Getting hold of the original Russian literature in the West would be very time-consuming. This is a much cheaper alternative and will do for most of us. This book is for you when you are interested in national dress and ethnography! You can order your print-on-demand or second-hand copy through the AbeBooks website. We were presented with a captivating book on Uzbek Gold Embroidery at the start of the International Festival of Gold Embroidery in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. This exquisite book, adorned with chapters on the rich history of gold embroidery, the vibrant community of gold embroiderers in Bukhara, materials, tools, techniques, and a catalogue of both historic and contemporary masterpieces, is a treasure trove for any embroidery enthusiast. Approximately half of the book is dedicated to stunning pictures of gold embroidery. Regrettably, only the chapters on the history of gold embroidery, the organisation of the gold embroiderers in Bukhara, and the catalogue are translated into English. Despite this, it is a book that undoubtedly deserves a place on your shelves! The book is authored by Bakhshillo Dzhumaev (or Jumayev), a seventh-generation gold embroiderer in Bukhara who has successfully passed on the craft to his son. Although I did not have the opportunity to meet him, I did meet his son and was graciously given a tour of the family business. However, the most significant encounter was with his mother, Muqaddas Jumayeva. She patiently demonstrated some typical Bukhara techniques of gimped couching. I also had the privilege of exchanging my broche for hers, a precious memento from my journey. The Jumayev family are the epitome of gold embroidery royalty, and I am deeply honoured that they shared their knowledge and craft with me. The chapter on the ancient history of gold embroidery mainly contains quotes from classical sources. Unfortunately, recent research has shown that we should be very careful with their interpretation. They are more likely to talk about woven textiles and not gold-embroidered textiles. However, archaeological finds from Central Asia and Uzbekistan, in particular, show that gold embroidery was known as early as the first or second century AD. Unfortunately, no reference is stated for these archaeological finds from a female grave in the Tashkent region made by M.E. Voronts. If you know of a publication, please let me know. More secure historical sources date back to the 15th century. The chapter on the art of gold embroidery of Bukhara is a real gem. From at least the 16th century onwards, Bukhara was the region's gold embroidery centre. There were two categories of gold embroiderers (again, a male profession with related females only acting as assistants when the workload required it): one group worked directly for the ruler in the palace workshops, and the other group worked in small family businesses located in town. In order to be able to quickly deliver larger orders, there was a labour division with many embroiderers working on the same piece. And just as is the case with medieval goldwork from Europe, pieces were not signed and almost never dated. The embroiderers were organised in a guild with a single guild master and his assistant overlooking production. This person was called an Aksakal. He was responsible for the fair distribution of the orders amongst the guild members and acted as a mediator between the palace workshops and the many private workshops. The guild also marked births, weddings and funerals of its members. Every year in the spring, there was a kind of a trade fair or festival called Guli Surkh. The embroidery masters would present their products there. Gold embroidery was inherited from father to son (and, in more recent times, also to daughters). If you learned from your father, you were considered a master. Sometimes, more distant relatives or the children of neighbours were also allowed to become apprentices. These apprentices went through a long training period before becoming a master. Similar to apprentices in Western Europe, they did not receive a wage but were given board and bed instead. Apprentices started with cleaning the workshop, then they were allowed to wind the broches (called patella), set up the slate frames (koruna) and finally were allowed to embroider flowers before being shown the more complicated techniques and patterns. Interestingly, storytellers would visit the embroidery workshops once or twice a week to read the guild regulations whilst the embroiderers were working. These regulations contained a history of the craft, rules on how the embroiderers were to behave towards their customers and their apprentices, the quality of the work and materials used, the cleanliness of the embroiderer and his workshop and the prayers that needed to be said before, during and after the work. The gold embroiderers also venerate a patron saint, Hazrat Yusuf. As we know, medieval guilds also had their patron saints; one wonders if there were 'work' prayers said also. Unfortunately, the materials, tools and techniques chapters do not come with an English translation. Neither do the many biographies of past and present gold embroiderers featured in the book. It has proven rather difficult to translate these parts from Uzbek into English. My normal method does not seem to work as Uzbek is too obscure a language. Nevertheless, I will try to find out what is written here as I have a feeling that it is quite important.

The second very important thing that eludes me at the moment is where to get the book. It has an ISBN number (978-9943-8192-9-0) but a search on the web does not return anything. A google image search of the cover did not return anything either. The publisher is Sahhof in Tashkent. And again, a search does not return anything. If you can offer any help here, please let me know so that I can share it with the wider embroidery community. Your assistance in this matter would be greatly appreciated! Literature Dzhumaev, B., 2022. Art of Gold Embroidery. Sahhof, Tashkent. Gleba, M., 2008. Auratae vestes: Gold textiles in the ancient Mediterranean, in: Alfaro, C., Karali, L. (Eds.), Purpureae Vestes II, Vestidos, Textiles y Tintes: Estudios sober la produccion de bienes de consumo en la antiguidad. University of València, València, pp. 61–77. After a successful week of teaching for Creative Experiences in Les Carroz, France, I decided to drive a further 330 km to visit Le-Puy-en-Velay. The Cathedral Treasury houses the Cougard-Fruman textile collection. Judging from the catalogue, the collection comprises of c. 180 pieces. Most of it is liturgical textiles. And a few pieces are medieval goldwork embroidery. The museum is well worth a visit. And even a repeat visit as the pieces on display rotate. The town itself is beautiful too with a medieval 'haute-ville'. It is also one of the main places in France from which to start the Camino pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. But let's have a closer look at one of the embroidered chasubles in the museum. It turned out that I was already somewhat familiar with it ... This is the said chasuble. It was made in Flanders (Brussels?) in the 15th-century according to the museum caption. On the front, we see Catherine of Alexandria above Philip the Apostle (identification uncertain). The cross on the back shows the Trinity at the top flanked by two angels. Below are Saint John and Saint Peter. Although the embroidery does not sport high-quality silk shading or brilliant or nue, the chasuble is a high-end piece. The composition of the Trinity with the two censer swinging angels on either side is balanced and full of movement. The string-padded frame within a string-padded frame for the central depiction of the Trinity also adds extra texture. The lining of the cloaks of the angels is made by couching a piece of blue-green heavy silk in place. The goldwork embroidery is executed with membrane threads. The membrane threads are now badly oxidised and dull. When the embroidery was originally made the threads would have looked golden and shiny. The silk embroidery is done with untwisted silk. I am a bit puzzled by the twisted textile thread used in the padded basket-weave border around the orphrey. It is reddish-brown and much duller than the silks. To me, it looks like wool. However, it might be a thick spun silk. From the pictures in the catalogue, I had not realised that one of the orphreys I bought at an auction is related to the orphreys on this chasuble. When I stood in front of the display case in the museum, it suddenly dawned on me that I had something similar. Luck will have it that I brought the orphrey with me for my students at Les Carroz to study. The museum personnel was very nice and helpful and they allowed me to fetch the orphrey from my car and bring it into the museum for comparison. How cool is that?! As you can see from the above picture of my orphrey, the materials, colours, style of the figure and embroidery techniques are quite similar to that seen on the chasuble in Le Puy. My orphrey is just very dirty and will need some TLC. It was glued onto velvet which was glued onto plywood. As the wood was mouldy, I had to remove the orphrey by cutting through the velvet and glue with a surgical knife. Not a delicate task. But it worked. I will write more on the orphrey and what I did to it in a future blog post.

But first, I am off to the International Festival of Gold Embroidery and Jewelery in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Got my flight tickets yesterday and will leave on Wednesday. As I will still be in Uzbekistan next Monday there will be no blog post. As always, my Patrons will be able to follow me on my travels. Literature Cougard-Fruman, J. & D.H. Fruman (2010). Le trésor brodé de la cathédrale du Puy-en-Velay. Centre des Monuments Nationaux. When we looked at the embroidered chasuble from Fritzlar with the Virgo inter Virgines iconography last week, I was sure that I would be able to find many Doppelgänger. I had seen this iconography many times before and I was quite sure that these pieces were all very similar. Nope. They are not. As soon as you start to look at these pieces in more detail you will find that they are all different. Either in the placement of the individual figures and/or in the embroidery techniques used. Now what does this mean? On the one hand, these pieces are readily recognisable as a group and on the other hand, they are all different. This, I think, must mean that there was a late medieval model book that was in use by embroiderers in Central Europe. As no medieval model books used by embroiderers seem to have survived, reconstructing one using actual medieval goldwork embroidery is pretty exciting. Here you see two typical embroidered chasuble crosses showing the Virgo inter Virgines from the late 15th century. The left chasuble was made in Austria in the second half of the 15th century and is kept at the Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts. The piece on the right is part of the private collection of the Bernheimer family. It was made in Southern Germany shortly before AD 1500. In both embroideries, Mary is depicted as the Madonna with child standing on the crescent moon with rays of light behind her. This 'Mondsichelmadonna' was very popular in the 15th century and refers to the Woman of the Apocalypse. On both embroidered chasubles the figures accompanying the Madonna in the large top orphrey are Catherine of Alexandria (with sword) on the left and Saint Barbara (with chalice) on the right. Everything else differs. No angel is crowning Mary on the Bernheimer chasuble. The figures in the two smaller orphreys below the Madonna differ for both embroideries too. On the left, we see Saint Apollonia (?) followed by Saint Ursula. On the right, we see Mary Magdalene followed by Catherine of Siena (?). When we look at the embroidery techniques used, there are differences but also many similarities. For starters, the colours used are very similar. There's mainly blue for Mary and a combination of green and orange for the other virgins. Both embroideries use the same diaper pattern for the golden background: open basket weave. Couched down with a yellow thread for the piece from Austria and couched down with a red thread for the piece from Southern Germany. The treatment of the halos is also identical. There's a layer of silken flat stitches as the base with a couched gold thread on top. The halo is edged with one of these composite threads: a thick textile yarn with a gold thread wound around it. This is sometimes called gold gimp in the German literature. These similarities in both iconography and embroidery techniques show that these pieces are made in the same geographical area. After all, Southern Germany shares a border with Austria. The differences show that the pieces were not made in the same town or guild. Likely, the customer could choose which additional figures to add to the central scene of the Madonna. These additional figures likely had some special meaning for the customer. As the iconography of the Virgo inter Virgines is strongly associated with convents, name days and patron saints of the nuns probably played a role here. And here you see the other main type of the Virgo inter Virgines iconography. The central top orphrey with the Madonna is very similar to that of the two previous examples (Catherine, Ursula, Barbara and Madonna). However, the two smaller orphreys below now show two saints each. We see Dorothea of Caesarea (basket) with Margaret the Virgin (dragon) and Saint Apollonia (thongs with tooth) with Mary Magdalene (ointment box). These two chasuble crosses are identical in their iconography. The treatment of Saint Ursula on a cloud above the Madonna is only seen on these two embroideries as far as I am aware. But there is more. There are other identical embroidery techniques too. See the bands that separate the different orphreys? They are made by couching silk and gold threads over horizontal string padding. And they are identical on both embroidered chasuble crosses. To me, this suggests that both embroideries were made in the same town. Will we ever find out which one? And when we look at the Saint Catherine's of all four embroidered chasuble crosses, they look pretty similar. How did this happen? In the 15th century, ecclesiastical embroidery had already evolved into mass production. Certain scenes were very popular and every self-respecting church wanted them. The 15th century also saw the invention of block book printing (major centres in the South of Germany) and the printing press (invented in Mainz, Central Germany). Likely, cheap block books with simple line drawings of the different Virgins existed in this geographical area too. These would have been used in the embroidery workshops as design inspiration. Designs would have been drawn free-hand or by using a grid to enlarge them more easily. Especially the faces differ between the various versions of a particular figure. This seems to be quite understandable as this is the hardest thing to get right in both drawing and subsequent embroidering.

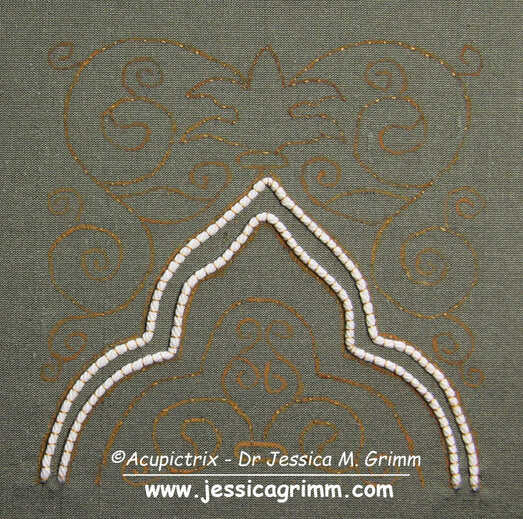

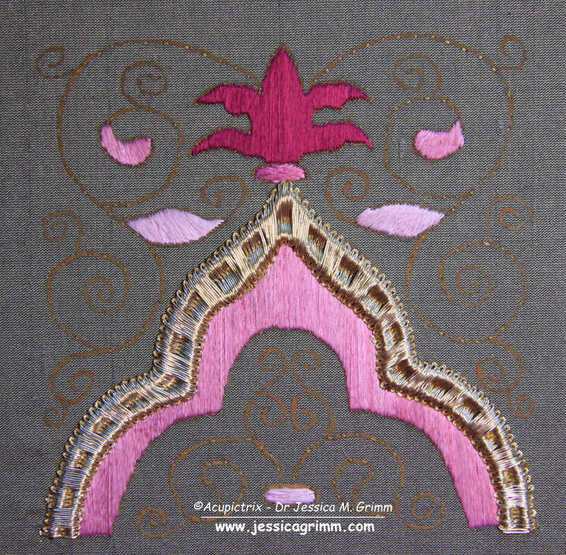

By consequently digitizing these embroidered figures into line drawings and combining these with the used embroidery techniques, I have a feeling that it should be possible to group them. This hopefully leads to more precise provenances for these embroidered chasuble crosses. It should also help with the identification of incomplete figures on cut orphreys. I am planning to spend my summer holiday learning how to digitize with the help of Inkccape. In the meantime, I am collecting the Virgo inter Virgines embroideries on a Padlet for my Journeyman and Master Patrons to enjoy. Next week, we will work a practical sample based on the above embroideries! Have you seen my new blog index? So far, all blog posts have been neatly indexed. You'll find a list of book reviews, my projects listed according to embroidery techniques, historical embroideries listed according to century and a complete list of all tutorials. Today's tutorial is all about the white string we see in many medieval goldwork embroideries. This padding is often all that remains from the original bead embroidery worked with freshwater pearls. When we are really lucky, a few pearls still adhere. As is the case for the chasuble I showed you two weeks ago. In this tutorial, I will show you how the padding and the beading were worked. I was really surprised by how sturdy this technique actually is. The beaded edge is VERY firm. As always, I worked my sample on a piece of high-count (think 40ct and up) linen stretched on my slate frame. I determined the approximate size of St John's head with nimbus from the original embroidery. It is about 5.3 x 5.9 cm. I made a pricking on transparent paper and transferred the design with pounce powder and ink. As is a favourite with medieval embroiderers, the simple nimbus is actually built up of several layers of embroidery. Start with a layer of radiating satin stitches in blue flat silk. The radiating does not need to be super precise. You can hardly spot the radiating stitches once the next layer of embroidery has been worked. The next layer consists of couched gold thread. Use a fine red silken thread for the couching. Work from the outside in. The first few rows consist of a double gold thread, whilst the last couple of rows consist of a single thread. In the original, the embroiderer would have hidden de turns under the slip of the head of St John. I have turned my threads on the edge of the nimbus. It is now time to add the actual string padding. It is made up of a twisted-together bundle of linen threads. These are couched down with white silk. Start from the middle and retwist your bundle as you go. The ends seem to be tapered in the original. To achieve this, start to cut away pairs of threads from your bundle about a cm before the end. Keep couching and removing pairs of threads until you are left with a single pair on the design line. Sew down the freshwater pearls (Etsy is a good source for these!) onto the string padding using white silk. You might want to wax your thread as the holes of the pearls can be quite rough. Go through each bead twice. In the original, the pearls are sewn down with a little bit of space between them. This was possibly done to save costs. It is said that the string padding was used to elevate the pearls away from the very shiny gold. It also provided a continuous white edging for when the pearls were slightly spaced apart to save on costs. The end result is very stunning!

As always, my Journeymen and Master Patrons find a downloadable PDF of this tutorial on my Patreon page. For as little as €5 per month, you can build your own library of medieval embroidery technique tutorials. Not a bad deal at all! Last week, we looked at a mid-15th century orphrey from Venice with an interesting goldwork background worked on silk. I've adapted the design slightly and turned it into a goldwork tutorial. The stitching is relatively simple but teaches you a few key things when it comes to medieval goldwork embroidery. Journeyman and Master Patrons find a downloadable PDF on my Patreon page. Becoming a Journeyman or Master Patron is an affordable way to obtain an archivable goldwork lesson each month. Let's dive in! The design should measure c. 10 x 10 cm. This is approximately the size of the original. However, I've squared it off a little to make it look like a Moroccan tile. It is best to work a project like this, there is some heavy goldwork, on a professional slate frame. Dress it with a layer of high-count linen (40 ct or up would be good) and apply a piece of silk on top. You can find my free video tutorial on the process here. Transfer the design any way you prefer. I've used prick-and-pounce and watercolour paint. You will need to fuse your silk to the linen with tacking stitches on all the major design lines. This is basically a running stitch with a short stitch on the top and a long stitch on the back. Use a gold-coloured silk or sewing thread for this. Next, attach the white string padding by couching it down securely with the same gold-coloured thread. The padding threads need to lay well within the design lines. The design line is where your gold threads will turn. You do not want the padded area to encroach on the rest of the design. Time to fill the appropriate areas with silken satin stitches. The original shows quite stark shading and the silken areas have a very stripey appearance. The satin stitches are also worked a little 'open' with some background fabric showing. Instead, I've opted for solid fillings. There is no split stitch edge beneath the satin stitches as all the edges are going to be covered with gold. This will neaten them automatically. (Please note: I forgot to fill in the two small leaves at the bottom!). Couch down the gold threads over the padding. Gold threads are couched down in pairs. Start in the middle of the shape. I've used Stech 70/80 which is comparable to passing thread #3. The couching rhythm is as follows: 5x with an extra couching stitch in between the padding threads and 5x without this extra stitch. Alternate all the way down. You will need to fudge a little as you start vertical, but need to end horizontal. Couch two single lines of gold thread in place on the pink area underneath the padded gold. How you end your gold threads is up to you. You can either plunge and tie back on the back or you can oversew on the front and clip. The 'only' thing left to do, is to cover the tendrils with couched gold. You aim for as few starting and stopping points as possible. And you try to hide starting and stopping under subsequent goldwork. This was common practice in medieval goldwork embroidery as it made the finished product more durable. And that's your goldwork project finished!

Wishing you all a lovely holiday season and all the best for 2024! Thank you for being such a loyal audience. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed