|

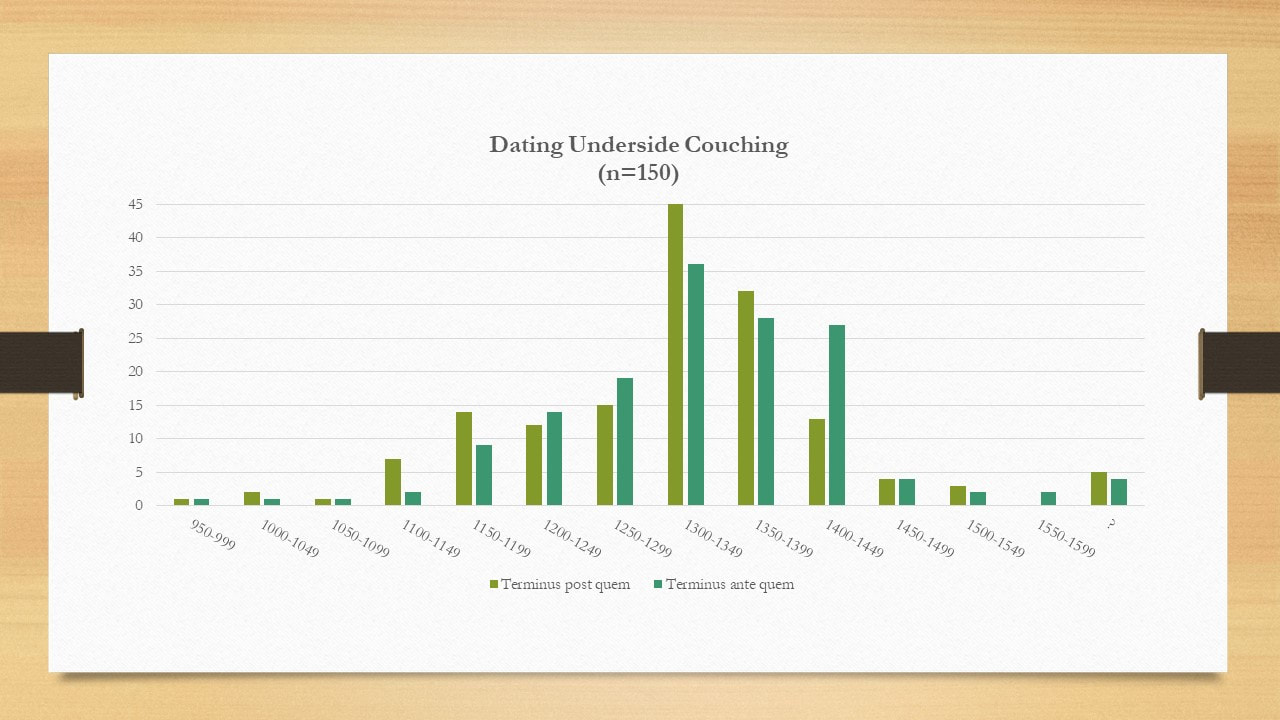

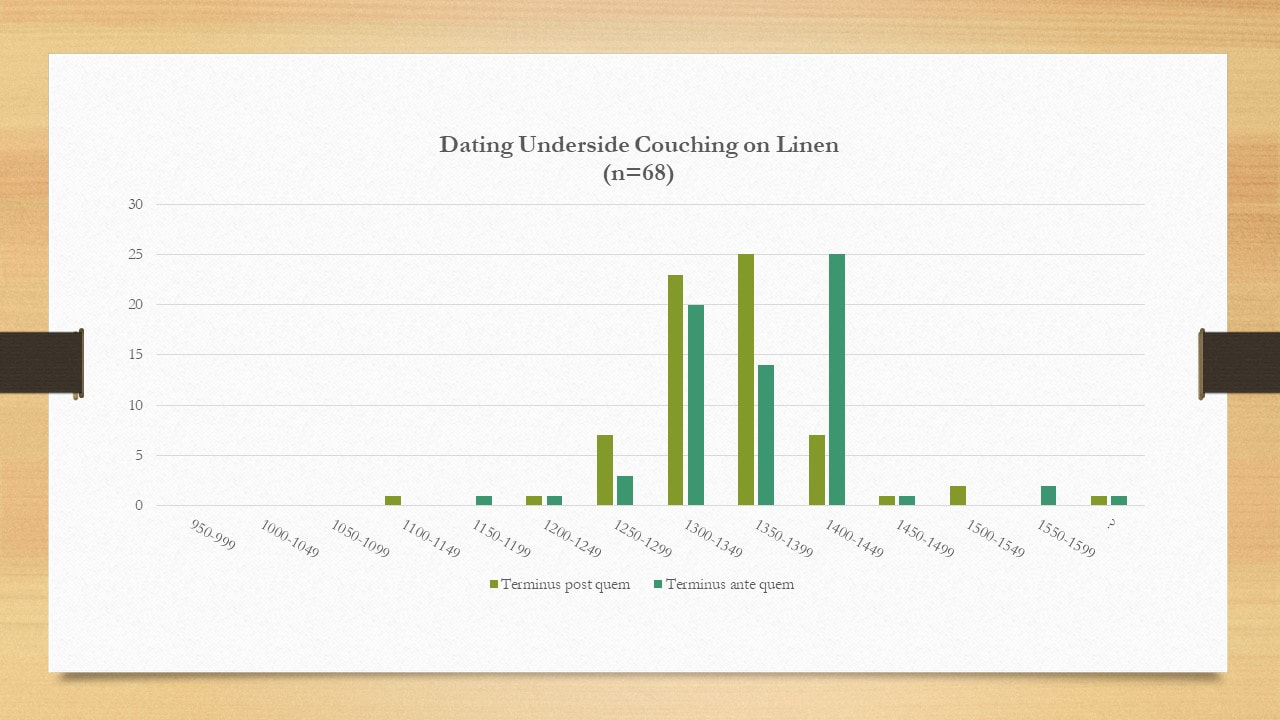

During my research into medieval goldwork embroidery, I came across a cope held in the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe Bezoeking church in Lissewege, Belgium. Although the beautiful cope hood was made in 1954 by the famous Belgian company Grosse of Brugges, the rest of the embroidery is much older. The literature dates the cope around AD 1500 and the online catalogue even as late as AD 1501-1600! This seems much too late to me. I have a suspicion that the cope is a composite piece. Embroideries from one or more vestments were combined into this new cope. Let me argue my case. For copyright reasons, I cannot incorporate pictures of the cope into my blog. Please click here for the online catalogue. You can change the language to English, French or Dutch. If you scroll down, you can see all the available pictures for this object. You can even download them (and zoom in even more) for private research! Firstly, if we look at the embroidery of the orphreys on either side of the front opening we see that the goldwork embroidery is executed in underside couching. Although the goldwork embroidery is badly damaged it is clearly underside couching. When I pull all the underside couched embroidery from my database of nearly 1500 medieval embroideries it becomes clear that the bulk of underside couched embroidery dates to the second half of the 12th-century until the first half of the 15th-century. The Belgian cope is dated to the (beginning) of the 16th-century and thus seems too late. If you look at the detailed pictures in the online catalogue, you'll see that the saintly figures of the orphreys on either side of the cope's opening have been cut out of the original fabric. They were subsequently appliqued onto the current red velvet and the seams were covered with a piece of twist (note the long linen? stitches that hold it all in place). Originally, these saintly figures were stitched onto linen. My database contains 68 pieces for which the base fabric of the underside couching is one or two layers of linen. These pieces seem to concentrate on the time period from the second half of the 13th-century until the first half of the 15th-century. We've narrowed the time period by about a century. When I saw the embroidery on the orphreys for the first time, they reminded me of the embroidery on the Clare chasuble and that on the Vatican Cope. Both date to the last quarter of the 13th-century. It also has some similarities with the figures on the Syon cope from the first quarter of the 14th-century. The figure of Mary with a lily in one outstretched hand and baby Jesus standing on her lap is very similar to the one seen on the Jesse cope. Also dating to the first quarter of the 14th-century. A date for the Belgian orphreys somewhere between the last quarter of the 13th and the first quarter of the 14th-century seems to be more likely. Just a note of warning: the silk embroidery in these figures is not all original. Just like the goldwork embroidery, the silk embroidery is quite damaged. And whilst the later embroiderers had probably no idea how to repair underside couching, they did know how to silk shade. You can clearly see the difference in the silk shaded areas (thicker silk also) and the original minutely split stitched areas. When the figures were origianlly made, their embroidery was of the highest quality! But there is more embroidery on this cope! The whole 'body' of the cope is 'powdered' with angels, double-headed eagles, fleur-de-lys and a large depiction of the coronation of the Virgin. This is not your classical Opus anglicanum. The goldwork embroidery is executed in normal surface couching and the silk embroidery is executed in vertical silk shading (also known as tapestry shading). These kinds of embroideries are of later date than the 'true' Opus anglicanum orphreys. From the sparse mentions in the literature, it becomes clear that these appliques were mass-produced in embroidery workshops in England and then traded within England and to Continental Europe. Literature from Continental Europe also states that it is likely that these appliques in the 'English style' were also produced locally. As these embroideries are generally considered inferior to 'true' Opus anglicanum, they have so far not gotten the attention they deserve. Their development and therefore their dating is poorly understood.

That's all for today. I hope you enjoyed the embroidery on the Belgian cope as much as I did! This piece seems to be unknown in the English-speaking embroidery scene. As I have been invited to study some chasubles in a museum in Görlitz, the next blog will be published on the 21st of March. Literature Browne, C., Davies, G., Michael, M.A. (Eds.), 2016. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press, New Haven. Versyp, J., 1955. "Engels" borduurwerk in het Noorden van Westvlaanderen. Artes Textiles II, 28–33.

7 Comments

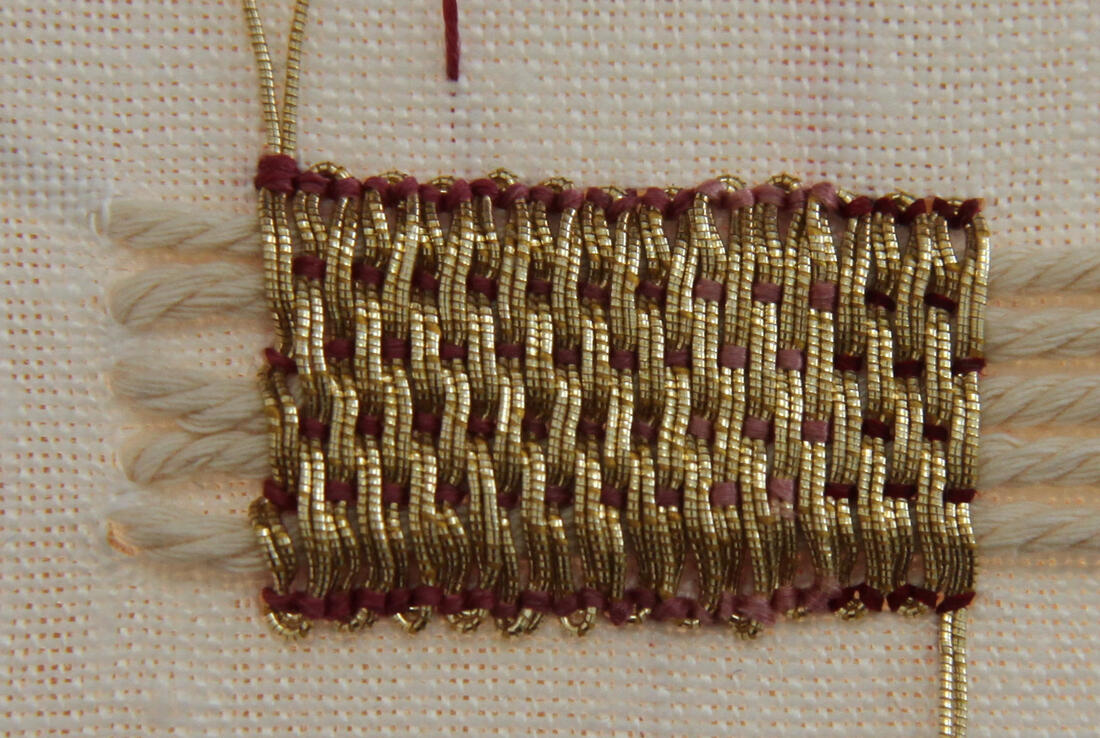

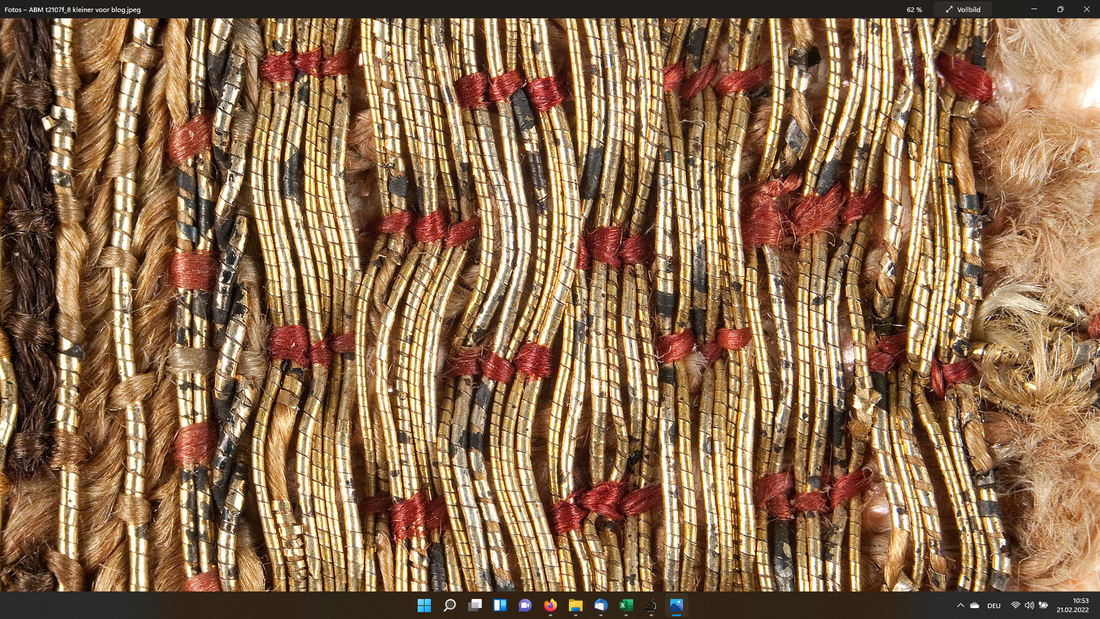

Last week, we discovered that the use of gummy silk in medieval silk embroidery is probably not very likely. The string-like nature of the gummy fibres and its inability to 'spread' makes it an unlikely candidate for long-and-short stitch or for or nue. Today, I would like to explore another important part of medieval goldwork embroidery: couching over padding. You'll sometimes find that the silken thread used for this is described as 'slightly thicker/stronger' than the other silken threads used in the same piece. As de-gummed silk is rather slippery, using it in couching down gold threads over padding isn't easy. You just can't maintain the necessary tension when using a single couching stitch. One way around this is to use two stitches on top of each other. However, the 'coarser' nature of the gummy silk would probably do the trick too. In addition, the gum lets the silk look fatter. Let's explore! For this experiment, I laid a simple foundation of cotton threads. It is rare that the nature of the padding threads is named in the literature, but cotton padding was definitely used in some Italian embroideries in the later medieval period (for instance the 14th-century panels held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art 58.139, 1975.1.1781, 60.148.1, 60.148.2, 60.148.3, 60.148.4, 60.148.5, 61.31 & 64.27.18). With the padding in place, I proceeded with a simple basket weave using a double passing thread. This pattern is commonly seen as a frame around late medieval orphreys from the Netherlands (for instance ABM t2109). As I had expected, the gummy silks worked very well. You can tension your couching stitch and lock your gold threads in place with a single stitch. The couching stitch does not 'spring back up'. Stitching is quick and efficient. In the above picture, you'll see that the completely de-gummed silk (lightest colour) was unable to hold the gold threads down. This has resulted in a less crisp couching pattern (very difficult to photograph, but clearly visible with the naked eye). Let's see what the couching stitches look like up close. Above is a picture with couching stitches made with gummy silk (left, first 6 rows) and partly de-gummed silk (right). And here is a picture with the de-gummed silk on the left (lighter colour) and a waxed 2-ply Chinese flat silk on the right. Simply lightly waxing the silk works similarly to using gummed silk. How do these modern samples compare to medieval embroidery? It all looks incredibly similar :). As you get the same result when you wax your silk thread lightly, I have a feeling that this is the way our medieval embroiderers went. Instead of having two different types of silk in stock with the added difficulty of colour matching, I think they just used beeswax. The above pictures prove that detecting either gum or beeswax in medieval embroideries can probably not be done without chemical analysis. Thanks to Dr Katrin Kania I was able to test the idea of gummed silk in medieval embroidery. I can now back up my arguments in future discussions of the topic with some hands-on experience!

Last week, Dr Katrin Kania, a fellow archaeologist and medieval textiles researcher, posted an intriguing article on her blog on gummy silk. In it, she mentioned a conversation she had had in the past with a conservator who had stated that medieval silk had a much firmer structure. This firmer structure probably has to do with the fact that this silk was only partly de-gummed (i.e. cleaned of silkworm spittle, the stuff that glues the silk threads together to form the cocoon). In contrast, the Chinese flat silk I like to use for my medieval embroideries is completely de-gummed. This results in a soft thread with a very high sheen. As I love silk and anything medieval, the combination of the two sounded like a real treat. In addition, questions on silk gum had also come up with my students. So, I ordered a spool of gummed silk from Katrin to see the stuff for myself. When it arrived, Katrin had kindly included some samples of the silk experiments she talked about in her blog. Time for me to test these in some simple stitching experiments! First things first. I started by taking macro-pictures of all the silk threads. When you compare the silk samples provided by Katrin with the Chinese flat silk, you'll see that Katrin's samples are all more twisted. Such threads are not ideal for for instance silk shading. With silk shading, you try to achieve a smooth surface for maximal sheen and optimal blending of colours. Additionally, the silks that still have gum in them are very stiff/stringy and don't feel like silk at all. When used in embroidery, they would not naturally 'spread' as embroidery silk does. This would create bumps when using in or nue. So, I don't think that gummed or partly de-gummed silk threads were used in the making of medieval orphreys. To illustrate this further, I have stitched a few samples. Here you see the four samples I have stitched using simple long-and-short stitch. From left to right: gummed silk, partly de-gummed silk, de-gummed silk and Chinese flat silk. Although very different in thickness, the de-gummed silk and the Chinese flat silk performed similarly. The thicker de-gummed silk from Katrin has just a little more twist than I would like. The two silks that still have gum on them were unsuitable for long-and-short stitch, just as I predicted. As the thread does not 'spread' it was difficult to cover the ground fabric completely. The surface looks very bumpy and unruly. I've also done some simple couching with a left-over piece of passing thread. Again, the de-gummed silk and the Chinese flat silk performed best. They produced uniform couching stitches. The silk with gum produced couching stitches of various thicknesses. How do my samples compare to the long-and-short stitched areas and the couching areas of medieval orphreys? Even though the silk on the face of St Lawrence has deteroriated somewhat, it compares best to the completely de-gummed silks. As various thicknesses of very fine silk threads were used, Chinese flat silk works best. As an embroiderer, you have total control over the thickness of your thread as you can split as you like. The same holds true for the or nue detail from St Lawrence. You can download a very high-resolution picture from the website of Museum Catharijneconvent so that you can zoom in even more. You will then also see that the couching stitches of the or nue lay flat and that there is a minimal twist. That's the same when you use Chinese flat silk. As long as you pay attention to your thread and let it 'dangle' every so often, you will have minimal twist too.

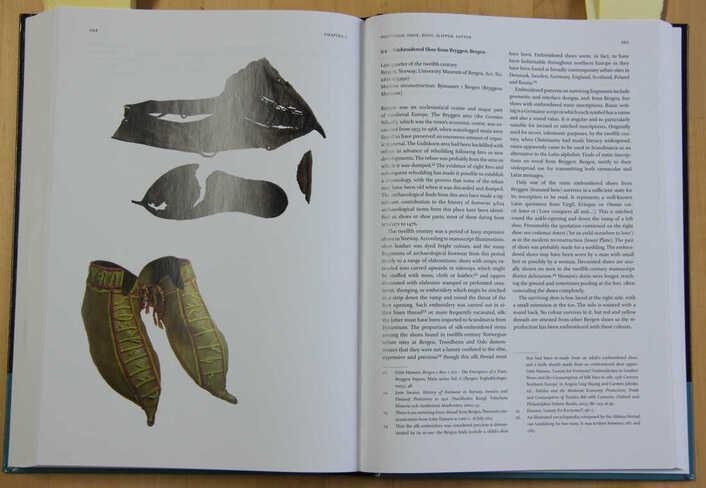

My conclusion is that the fine embroidery on medieval orphreys was made with fully de-gummed silk. Comparing my samples with the close-up pictures in the publication of the Imperial Vestments held at Bamberg also shows that they were made with un-twisted fully de-gummed silk. Literature Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2020. Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung: Rekonstruktion der tausendjährigen Veränderungsgeschichte. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg. Today, I am going to review a book that has been published about four years ago. Just like me, you might have missed this one; it isn't primarily about embroidery. In addition, with a selling price of €215/$247, it is rather expensive. It is always nice to read a bit more about an expensive book before you commit. The full title of the book is: Clothing the Past: surviving garments from Early Medieval to Early Modern Western Europe. The authors, Elizabeth Coatsworth and Gale R. Owen-Crocker are leading experts in the field of medieval studies and medieval textiles. So let's explore what's between the covers of this 435-page book! As said, this book is not primarily on embroidery. But since textiles of the upper classes were often decorated with embroidery AND these textiles had a better chance of survival, quite a few pieces with lovely embroidery are described in this book. This difference in survival chances between textiles of different social groups is discussed in the first chapter of the book: the General Introduction. One of the strengths of this publication is that the authors have tried to include as many 'everyday clothes' worn by 'everyday people' as possible. This has resulted in the inclusion of many archaeological finds from York (UK), Monasterio de Santa Maria La Real de Huelgas (Spain), Bocksten (Sweden) and Herjolfsnes cemetery (Greenland). Preservation issues regarding burial conditions in archaeological excavations (including tombs) are also touched upon. For instance, linen does not usually survive in an archaeological context; it rots away. Hence the misconception about medieval people not wearing underwear. In total, 'portraits' of about a hundred textile pieces are grouped together in 10 chapters. We move from head to toe and from outer garments to socks and underpants. Each of these chapters starts with an introduction in which relationships, similarities and differences between the pieces in a particular chapter are discussed. Each chapter has at least several embroidered pieces in them. New to me were the textiles from the Royal tombs in the Monasterio de Santa Maria La Real de Huelgas. Have a look at this spectacularly embroidered and beaded Spanish Birette found in the tomb of Prince Fernando de la Cerda (AD 1255-1275). Each 'portrait' consists of a picture or pictures of the piece and a description with plenty of citations for further reading. I got the feeling that the authors were more comfortable with sewing than with embroidery. The construction of the different garments is discussed in greater detail than the embroidery. For me, the gold standard of describing embroidered pieces are to be found in the publications of the Abegg Stiftung. However, as this book is published in English but contains so many pieces originally published in German, a Scandinavian language, French or Spanish you are bound to find information that is new to you. And when you then decide to dive into the original publications you have an idea of what they are about. So: is this book for you? That's a little difficult to answer. For those of you who like to look at close-up pictures of pretty embroidery for inspiration; this book disappoints. There are no such pictures and the description of the embroidery is too flimsy. However, if you are interested in medieval textiles in general and archaeological textiles in particular; this book is for you! I have read it from cover to cover and placed many post-its throughout the book for revisiting later (and I've ordered suggested literature through second-hand websites!). As the book is quite expensive and has such a large scope, you might want to try to order it through your library first and then decide on a possible purchase.

Coatsworth, E., Owen-Crocker, G.R., 2018. Clothing the past: Surviving garments from early medieval to early modern Western Europe. Brill, Leiden. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed