|

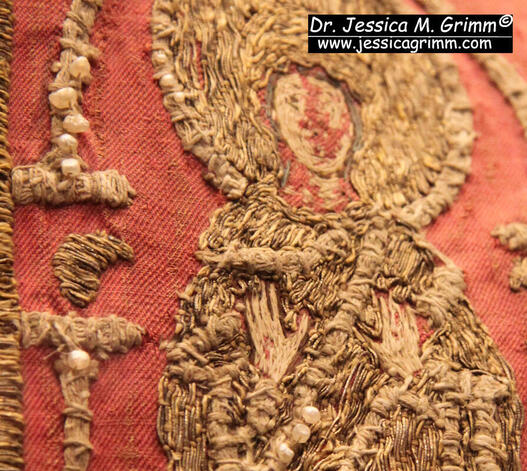

The 14th century Grandson Antependium. It is a pretty mix of embroidery techniques, styles, languages and geographical areas. Let's explore! The Grandson antependium is housed at the Historisches Museum in Bern, Switzerland and catalogued under Nr. 18. It is 244 cm wide and 88 cm high and consists of three separate parts. The knight kneeling to the left of the central figure of the Virgin and Child is the donor of the piece. His coat of arms identifies him as Othon de Grandson (c. 1238-1328). Although born near Lausanne in Switzerland, he became a close friend of King Edward I of England. Othon de Grandson travelled widely throughout Europe and the Mediterranean area when he joined the 9th Crusade. Othon accumulated great wealth and donated it to various religious institutions in both England and Switzerland. This particular antependium was donated to the Cathedral of Lausanne where Othon is entombed. With the amount of gold used for the embroidery, it must have been a very expensive piece. The central part of the antependium shows the enthroned Virgin and Child with two vases with foliage and two angels with censers on either side. The design has a Byzantine flavour which is emphasised by the Greek embroidered inscription for the name of Christ. But that's not the only language used. Mary is addressed in Latin and the two angels are addressed in ancient French. The design isn't purely Byzantine either: the censers are distinctively Western European. Byzantine embroideries with embroidered donor figures are not known in this era either. Where was this piece made? And for whom originally? Most scholars now agree that the central part of the embroidery was likely made in Cyprus. The island is conveniently placed en route to the Holy Land and also served as a retreat base when things went wrong during the crusade. Cyprus belonged to the Byzantine Empire with its Eastern Orthodox version of Christianity. At the same time, it had ample visitors from the West. Was the central composition mostly finished when Othon saw it at a Cypriot embroidery workshop? Where the texts added on his request? The knightly figure and the coats of arms certainly were. And then we have the two separate side panels. Very different from the central panel. Style, embroidery technique and materials used differ from the central panel. And their design is non-religious. The side panels are thought to have been embroidered in England as they sport underside couching. Is this a rare remnant of non-religious opus anglicanum? Did Othon come across two embroidered soft furnishings in England that together with the panel he probably acquired in Cyprus would make up a fitting antependium for the high altar in his cathedral back home? As the embroidery is cut at the top, the two panels were not specifically intended for that high altar when they were made. I think we see a rare glimpse of opus anglicanum 'for the noble home' preserved in this extraordinary antependium. What do you think? Literature

Martiniani-Reber, Marielle (2007): An exceptional piece of embroidery held in Switzerland: the Grandson Antependium. In Matteo Campagnolo, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (Eds.): From Aphrodite to Melusine: Reflections on the Archaeology and the History of Cyprus. Geneva: La pomme d'Or, pp. 85–89. Stammler, Jakob (1895): Der Paramentenschatz im historischen Museum zu Bern in Wort und Bild. Bern: Buchdruckerei K.J. Wyss. Schuette, Marie; Müller-Christensen, Sigrid (1963): Das Stickereiwerk. Tübingen: Wasmmuth. Woodfin, Warren T. (2021): Underside couching in the Byzantine world. In Cahiers Balkaniques 48, pp. 47–64.

1 Comment

A couple of weeks ago, I and my husband visited the lovely Diocesan Museum of Eichstätt. Apart from the normal sacral art on display, were a few important medieval vestments. The most interesting of them all is the so-called chasuble of St Willibald dating to the 12th-century. Goldwork embroidery was either made in Byzantium or in Cyprus according to the meagre information displayed in the museum and the literature. Originally, the shape of the chasuble would have been bell-shaped. The yellow silk twill dates to the 12th-century as well and was either made in Italy or in Byzantium. Although the chasuble is attributed to St. Willibald, he never wore it. St. Willibald was the founder of the diocese of Eichstätt und lived c. AD 700-787. Being the son of a Wessex chieftain and with a host of saintly relatives, he seems to have been predestined for the job! Depicted on the back of the chasuble are Jesus and Mary with 10 Apostles. Each figure is depicted under a Romanesque arch. The persons are identifiable through their stitched Greek names above the arches. The embroidery is worked on a strip of red silk twill. The goldthreads are couched down in pairs in a characteristic slanting couching pattern. Today, we are used to a couching pattern forming a brick pattern. However, a pattern forming a simple slant was very popular in the medieval period. As a rule of thumb: medieval embroideries where a single goldthread has been couched down are older than those where two (or more) goldthreads are couched down with each couching stitch. In this detail of Mary, you can see that her face and hands are stitched with small silken stitches. The literature states that these are stem and chain stitches. However, it looks more like irregular split stitch to me for the hands and typical "contour-following" split stitch as seen in Opus Anglicanum, for the face. Especially the latter can look like very fine chain stitches. The literature also states that Mary and Jesus were originally the only figures where the halo, architecture and clothing were further decorated with pearls. However, if you look carefully at the picture of the Apostle, you spot pearls there too. Just imagine what these embroideries once looked like with all the pearls still intact! As the pearls were padded with the beige string (linen or cotton) you see almost everywhere in these embroideries, the pearls would have sat proud of the surface catching the light better. The front of the chasuble was incredibly difficult to photograph due to a piece of modern art being right behind it. But you get an impression from the picture above. It is the same type of goldwork embroidery as seen on the back. Interestingly, many more pearls have survived on the front.

Unfortunately, it is unknown how this splendid piece of Byzantine embroidery ended up in the Cathedral treasury of Eichstätt. However, Eichstätt was an important Diocese in the Middle Ages and still has a Catholic University and Seminary. Literature Müller-Christensen, S., 1955. Sakrale Gewänder des Mittelalters. Hirmer, München. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed