|

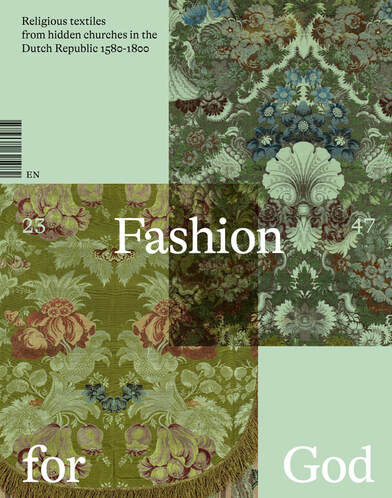

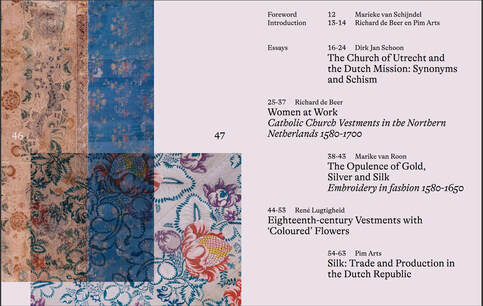

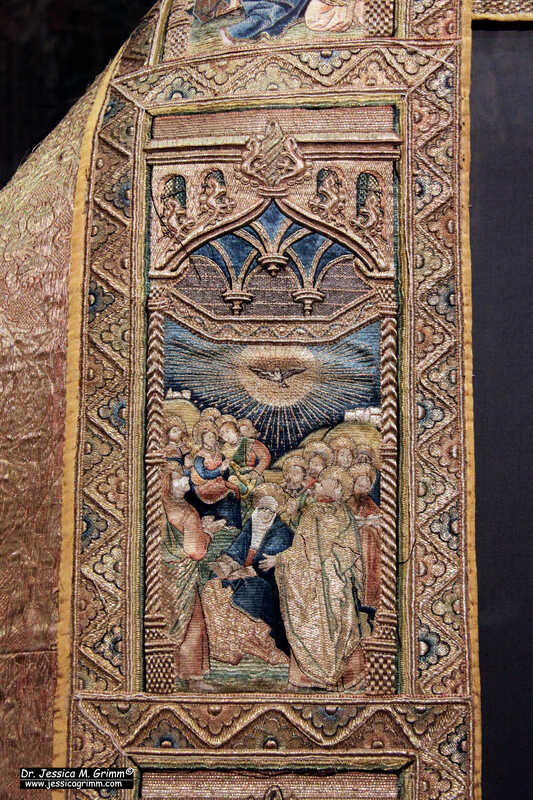

Before I let you know what I think of the catalogue accompanying the latest textile exhibition of Museum Catharijneconvent, I have some lovely announcements. Firstly, I have been re-invited to join the International Festival of Goldwork and Jewelery in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Two years ago, I sadly couldn't honour the invitation as I was very sick with Covid. So, fingers crossed that I stay healthy this time! Secondly, I have been notified by the Royal Dutch National Library that they will yearly archive a copy of my website and make it available in their collection. That's pretty cool too, I think! And now on to my book review proper. Last year, I visited the exhibition 'Fashion for God' (Religious textiles from the clandestine churches of the Northern Netherlands 1580-1800) in Museum Catharijneconvent in the Netherlands. It was the long-awaited sequel to 'Middeleeuwse Borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden' (medieval embroidery from the Netherlands) from 2015. And it was very much 'Dirty Dancing' and 'Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights' :). I only watched that sequel as Patrick Swayze had a teeny-tiny part in it. I only went to this exhibition as there would be a few medieval vestments on display that are hardly ever on display as their respective churches still own them. And it was a joy to be able to study them up close and take as many pictures, with sufficient light, as I liked. I also learned a lot about how these vestments survived and what the role of certain people and groups of people was. And I bought the catalogue for the sake of completion. Flicking through it before buying, it didn't exactly shout 'quality'. And now that I have read most of it, I don't know if I want to cry or start to laugh hysterically... The layout of the book, in my opinion, is a disaster. Pages with text have different background colours, the typeface is HUGE and pages with detailed pictures have been inserted at random as to imitate a fabric sample book. The paper of these 'fabric samples' is flimsy. There's an awful lot of empty space on the pages. The same information could have been printed on a fraction of the pages. Why this waste? Why not use a normal-size typeface and fill the pages properly? Use the freed-up space for close-up pictures of the embroidery or the fabrics, please! There are no close-up pictures of the embroidery in this book. Pretty odd for a book with embroidered textiles in it. The book consists of two parts. In the first part, there are five essays written by the Old Catholic bishop of Haarlem, a curator and a former curator of the museum, and two art historians specialising in (embroidered) textiles. Only one essay is well written. The others barely scratch the surface of the subject and just don't flow. One even has a pretty big omission/mistake regarding the types of gold thread used in medieval Dutch goldwork embroidery. But what is really missing from this part of the catalogue is a thorough essay on the embroidery and tailoring techniques used in the making of post-reformation catholic vestments. Why is this missing? After all, the socio-economic analysis shows that we move from (male) professional to (female) non-professional makers. Surely this is reflected in how things are being made. The second part of the book consists of the catalogue proper. There are 48 entries. Written details of the embroidery are very sparse. And since these are not illustrated with close-up pictures; good luck to the reader.

And the worst thing? The catalogue of the 2015 exhibition was only available in Dutch. Very disappointing for most of you and not good practice when you own a world-class collection. This one is available in English also. But why would you want one? At most, it serves as a list of textiles available in the Netherlands that you can then track down for proper study. Don't get me wrong. The exhibition itself was lovely. The fact that you can see many of the textiles up close and in sufficient light (often not even behind glass) is fantastic! And I really learned a lot about the religious women and some men who saved and preserved the late-medieval vestments and made new ones in the old style. But if you hoped to get a good impression of the exhibition through the catalogue, you will probably be pretty disappointed. When they did the medieval exhibition in 2015, all the pieces in the collection of the museum were photographed and made available in high-resolution online. Not so this time. So, you can't even use the paper catalogue as a starting point to enter better close-up pictures in their online catalogue. What a missed opportunity. Literature Beer, R. de & P. Arts (2023), Fashion for God. Religious textiles from northern Dutch hideaway churches 1580-1800, Waanders Uitgevers Zwolle/Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht.

3 Comments

One of the reasons for writing my weekly blog is to introduce you to medieval embroidered pieces that are in collections outside the UK and the US. Due to the language barrier, these pieces are often hardly known in the English-speaking world. This has led to such strange ideas as "stumpwork was invented in 17th century England" and "Opus anglicanum was only practised in England". Sorry to disappoint you, but both assumptions are wrong. One such collection is in the Bernisches Historisches Museum in Switzerland. A couple of weeks ago, we looked at an Antependium made in Vienna for Königsfelden Abbey. Today, I'll introduce you to another embroidered antependium from the same Abbey. It is very different from the first. The above antependium or altar cloth measures about 3.18 m x 0.90 m. The background fabric is probably not original. The embroidered figures are about 60 cm in height. In the middle, we see the crucifixion with Mary and St John on either side. These figures were likely embroidered in the Upper Rhine area. The other figures (St Peter, St Catherine and St Agnes on the left and St Andrew, John the Baptist and St Paul on the right) were probably embroidered in Königsfelden Abbey. How do we know? The padding material in the embroidery is parchment. During an extensive restoration in 1889, some of the parchment was removed from the back of the figures. Besides a cut-up breviary, they also found the remains of a letter between Queen Agnes of Hungary and Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria. Clever historical research by Jacob Stammler, later bishop of Basel, revealed that this letter was written between 20 October AD 1334 and 20 October AD 1335. The fact that a trivial letter to Queen Agnes was used to pad parts of the embroidery indicates that the embroidery was executed where she resided: Königsfelden Abbey. The style of the figures points to c. AD 1350 as the date for the embroidery. Personally, I quite like to read 19th century papers on medieval embroidery. I love the tone (scholarship with a splash of Ivanhoe) and the beautiful technical drawings. Quite often, the embroidery was better preserved over a 100 years ago and the drawings clearly show that. However, there is a caveat: research marches on. The aforementioned bishop Jacob Stammler was quite convinced that Queen Agnes herself professionally embroidered and was quite capable to produce an altar cloth such as the one shown in an earlier blog post. After all, her biographer said that she was proficient with the needle! Nowadays, we know that these (former) queens were far too busy to embroider professionally. With all the diplomacy they conducted for their families and the overseeing of the royal household, they were probably as busy as any female CEO is today. Good luck embroidering professionally at the same time ... So, who did embroider the additional figures on this second antependium used at Königsfelden Abbey? As Queen Agnes resided at (near?) the abbey for many years and was very active in international diplomacy with many visitors and envoys coming to see her, she basically set up court there. It is thus likely that she had a royal workshop as well. The embroidery on this second antependium is of far too high quality to have been worked by part-time embroidering nuns. This is the work of professionals. The fact that the saints chosen to accompany the central crucifixion scene have a relationship with Queen Agnes and her family (St Andrew for her late husband and St Catherine for several female relations) shows that she was, however, actively involved in choosing the design. If you would like to read the original paper by Jacob Stammler, you can find it here. As it is written in Fraktur, I've prepared a transcript and a translation for my Journeyman and Master Patrons.

Let's visit some gorgeous medieval goldwork embroidery from Lausanne Cathedral and currently kept in the Bernisches Historisches Museum in Switzerland. When medieval embroidery is your thing, this is a museum you definitely want to visit. Apart from the vestments from Lausanne Cathedral and many others, the museum also has the Grandson antependium from the 13th-century on permanent display. The set of golden vestments from Lausanne Cathedral consists of a cope (inv. 307, now on display), a chasuble (inv. 39) and two dalmatics (inv. 38 & 40). The embroidery was made between 1513 and 1517, probably in Brussels, Belgium. This expensive set of vestments made with Italian fabrics and very high-quality orphreys from the Low Countries was commissioned by Bishop Aymon de Montfalcon of Lausanne. Aymon clearly had deep coffers! As Mary is prominently displayed on many of the orphreys it becomes clear that the vestments were always intended for Lausanne Cathedral which is dedicated to Our Lady. The design drawings on the linen underneath the embroidery were made with black and red ink. The correct shading is also indicated with the ink. There is not a full-colour drawing beneath these embroideries. It is more or less sparse monochrome-shaded drawing. Enough so the embroiderer was aided during his work, but not so strong that it obscured the weave of the linen fabric and made the actual embroidery harder. It is important for the embroiderer to still be able to see the weave of the fabric as the silk shading is more akin to Chinese silk shading (very orderly and counted) than it is to the type of silk shading taught at the Royal School of Needlework (which is random). Although all orphreys on all four vestments clearly belong together and were thus made around the same time in the same place, they do differ slightly in the execution of the embroidery techniques. I am sure you can separate out several different embroiderers when you study these orphreys in depth. The designs also differ quite a bit stylistically and were clearly inspired by several contemporary painters such as Gerard David, Bernard van Orley and Cornelis Engebrechtsz. Simple 'one saint' orphreys from the Low Countries often consist of two or more pieces sewn together: a separate saint appliqued onto an embroidered background (of which some very dimensional elements might also be slips). The more complex orphreys of the golden vestments are mostly worked as one piece with only some figures being worked as slips. This is probably easier (and thus quicker) when you have many partly overlapping figures in a single scene. The backs of the orphreys have been stiffened by gluing used paper onto them (letters, invoices, etc.). Interestingly, true or nue is absent from these orphreys. Instead, most figures are stitched in a form of silk shading. The main figures in the foreground may have parts of their clothing stitched with goldthread. However, the horizontally laid goldthreads are couched in a bricking pattern using gold-coloured silks. The folds are accentuated with some simple line stitches in coloured silks. I have coined the term 'pseudo or nue' for this specific embroidery technique. It is often seen on orphreys from Germany, but rare on orphreys from the Low Countries. True or nue can create fantastic shading and suggest three-dimensionality. Pseudo or nue cannot achieve this. The floral frames around the orphreys are also unique. So far, I have not come across a similar pattern with coloured flowers. This might have been a trademark of this specific embroidery workshop.

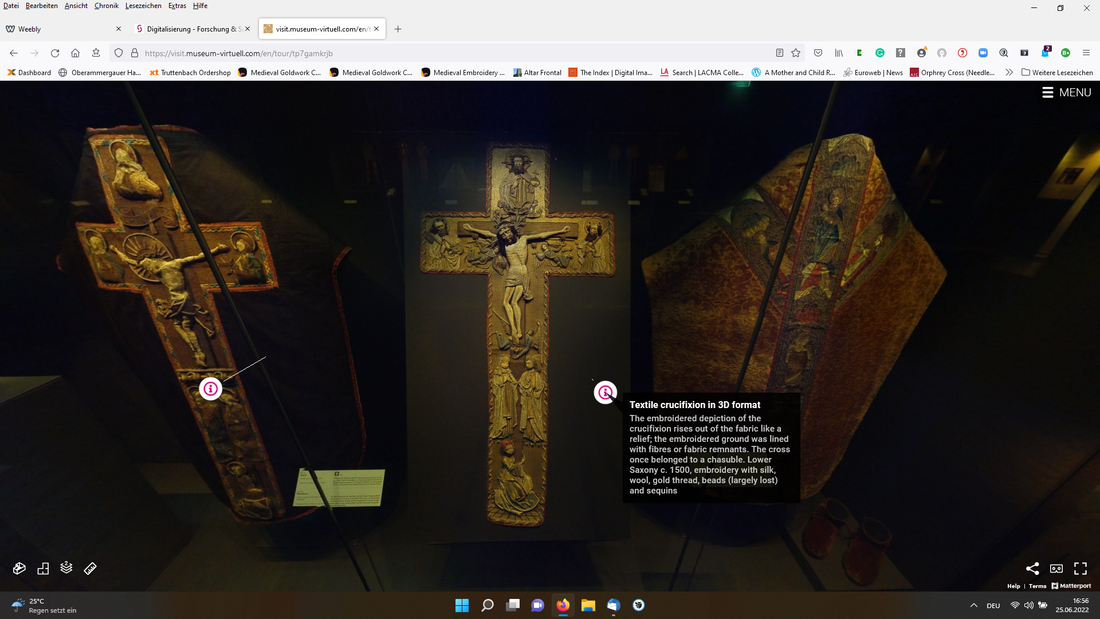

If you would like to learn more about the golden vestments from Lausanne Cathedral then please buy the museum publication "Himmel und Hölle in Gold und Seide" by Annemarie Stauffer. There is also a French version available. The book has detailed pictures and descriptions of the orphreys of all four vestments. The introductory chapter is also very well written. You can order the book (22 Swiss Francs) directly from the museum shop by sending them an email. Please remember: when you order from the museum directly you help them financially. Something museums can really use after the many closures during the pandemic! In a bit to compensate people for the high energy prices, Germany offers regional transport tickets for only nine Euros per month during June, July and August. Apparently to get commuters out of their cars and into public transport. Good luck to those of us living rurally. For example, my husband. He works in Ettal. That's only 18 km from where we live. He starts work at 9:30h. Public transport can either get him there at 7:20h or 9:50h. He ends work at 17:30h. Last travel option 17:05h. My husband would be perfectly willing to have a public transport commute of 45 minutes instead of the usual 20 by car. However, he is simply unable to take up the offer as there is no public transport available. On the upside: I use my ticket to do a bit of research travelling! Yes, it takes a long time to paste regional trains together to get from the South of Germany to the North, but it is practically free. Besides, there are only regional trains running when you go from the South to the East on many routes. Something that was never fixed since the wall came down. You also need to be flexible as the trains are very crowded and there is no guarantee that you can be transported. So, what did I visit? Three of the most important medieval and Renaissance textile collections in the world. We'll kick off with two of them: Domschatz Halbertstadt and St. Annen Museum Lübeck. My travels started off in Halberstadt. The cathedral treasury houses one of the most important cathedral treasures in Europe. It is probably also one of the museums with the largest permanent display of medieval textiles. Over 70 pieces, from luxurious patterned silks, to amazing goldwork embroidery to stunning whitework and huge tapestries, can be seen. There are only two major downsides: the level of lighting is so poor that you will have a hard time seeing the embroidery clearly. And secondly: you are not allowed to take pictures (which I doubt you can without flash anyway). Modern LED-lighting concepts for museums can allow for a better visitor experience but this costs money. Luckily, there is a beautiful publication (see literature list at the bottom of this post) which has beautiful colour pictures and detailed descriptions of about 60 pieces. It even contains many close-up pictures where you can literally see every stitch. There is also a full collection catalogue underway which will be published through the Abegg Stiftung. In my personal opinion, their publications are the gold standard when it comes to embroidered textiles. When you are interested in medieval embroidery, the Domschatz Museum should be on your 'to visit list'. You can easily spend several hours here. I'll recommend that you come prepared and have read the below-mentioned publication. This way you'll have so much more information as the museum captions are rather anecdotal. For those of you who cannot visit in person, the museum website has an excellent digital tour. Click on 'menu' at the top right and choose between DE or EN for language. Then click on the door opening. Depending on your internet connection and your device, be patient while the application loads. Click on 'floor selector' bottom left and choose 'floor 2'. The textile rooms are on either side of the main structure. Left for the whitework and the tapestries and right for the embroidered vestments. Enjoy! From Halberstadt, I travelled on to Lübeck in the North. That's almost 900 km from home :). The St Annen Museum is located in a former convent and also houses one of the most important textile church treasures in Europe. Due to the peculiarities of (recent) European history, Lübeck houses the treasury of St. Mary's church in Gdansk (formerly Danzig). For conservational reasons, only a tiny fraction is on display at a time (check the website to see which pieces). However, recently a complete collection catalogue was published (see literature list below). The texts are detailed, but could contain a bit more on the embroidery in most cases and not all pictures are as detailed as an embroiderer wishes. Nevertheless, it is a must-have addition on your shelves when you are into medieval (embroidered) textiles. My main reason for visiting the St Annen Museum now, was that the cope hood with a stumpwork version of St Georg and his pet was on display. This stunning piece of stumpwork embroidery was made around AD 1500 in Northern Germany. Sorry for those of you who think that stumpwork is an English invention. It is not. It was invented on the continent a good 100 to 150 years before 17th-century English stumpwork was made. Due to language barriers and not much appreciation on the side of art historians, these pieces have not gotten the scholarly attention they deserve. St George and his pet are pretty high on my recreation wish list :). Unfortunately, the construction of his head needs the help of a specialist wood cutter and a lot of trial-and-error. But this is definitely something I want to tackle in the future!

Literature Borkopp-Restle, B., 2019. Der Schatz der Marienkirche zu Danzig: Liturgische Gewänder und textile Objekte aus dem späten Mittelalter. Berner Forschungen zur Geschichte der textilen Künste Band 1. Didymos, Affalterbach. Meller, H., Mundt, I., Schmuhl, B.E.H. (Eds.), 2008. Der heilige Schatz im Dom zu Halberstadt. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg. Two weeks ago, I spent a very enjoyable day in the storeroom and the permanent exhibition of the cultural history museum in Görlitz, Germany. Curator Kai Wenzel facilitated my visit and together with my husband, we studied the five medieval embroideries kept at the museum. Görlitz lies in the historical region of Upper Lusatia and is bordered by the historical regions of Silesia and Bohemia. Today, these historical regions are divided up between Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. Most of the literature concerning medieval embroidery from these regions is a little older and not available in English. There is no comprehensive overview of all the medieval embroidery that has survived in modern museum collections and church parishes. Alfred Schellenberg published some preliminary overviews of what he called 'Silesian' embroidery in the late 1920s. His publications first drew my attention to this group of embroideries. As the map of Europe has changed quite a bit in this region after the Second World War, tracking the embroideries from his publications is a bit of a puzzle. Some are in Görlitz, others in several museums in Poland. By and by, I will try to track them all and arrange visits. Today, I'll introduce you to a chasuble cross that you can go see for yourself as it is displayed in the permanent exhibition of the cultural history museum in Görlitz. Meet 15th-century chasuble cross 61-03b on loan from the Evangelische Innenstadtgemeinde Görlitz. The chasuble was originally kept at the Peter and Paul church in Görlitz. As Martin Luther was not opposed to keeping using these catholic vestments after the reformation, this particular example is quite worn. Despite its worn state, it was transferred onto this newer chasuble in the 19th-century. This reminds us that these pieces were still being valued hundreds of years after they were originally made. To a modern viewer, their worn state makes them perhaps less worthy of display and proper research. Especially as there are contemporary paintings and sculptures which have survived in a much better state. These are often seen as more beautiful and they appeal to a larger audience. However, look closer and there is a lot to be discovered. This was once a beautiful and high-quality piece of embroidery. When you are a regular reader of this blog you might have a sneaky suspicion that you have seen a very similar chasuble cross before. Or even chasuble crosses. Well spotted! The scenes on this chasuble cross went viral in the 15th-century. They convey the story of Mary and baby Jesus in simple, easily recognisable pictures. The story reads like a comic book and usually starts with the angel telling Mary that she will be with child (Annunciation), pregnant Mary meets her pregnant cousin Elisabeth (Visitation), baby Jesus lies in the manger with Mary, Joseph and the as and oxen in attendance (Nativity), the Three Kings visit Mary and baby Jesus (Adoration of the Magi), circumcision of baby Jesus & presentation at the temple of baby Jesus. Depending on the space on the chasuble or local preferences other scenes could be added (Flight into Egypt, Massacre of the innocents, Jesus amongst the Doctors). Because these embroidered scenes are so generic, art historians can only broadly date and locate them on stylistic grounds. However, I have a feeling that when we look closely at the used embroidery techniques, we might be able to group some of these embroideries together. These groups might then represent different dates, geographical locations or even stitchers and workshops. The art historians can then try to argue which of these it is based on comparisons with other, better dated and located art forms. So let's start with this chasuble cross. Let's dissect the main scene with the Nativity. How many different embroidery techniques can you spot? - background and figures are worked in one go (versus figures are stitched separately and appliqued onto a separate background) this seems to be a characteristic that might zoom in on the dating of these pieces. - there's padded basketweave couching in the frame that goes partly around the scene. Gold threads (likely silver-gilt membrane with a white linen core) alternate with blue and pink coloured silk to form triangles. The string used for the padding has a strong Z-twist. This particular treatment of the frame around the orphrey is probably one of the characteristics on which basis groups of similar embroideries might be formed. - the now heavily corroded and worn golden background shows a very common couching pattern in red silk: closed basket weave (the little 'diamond' formed inside the 'weave' is filled with additional couching stitches). Although the couching pattern is the same for all orphreys, the silk used is yellow/white for the scene with the Annunciation and in the Visitation both this yellow/white and red are being used. The reason for the use of different colours and even two colours in one scene is not really apparent. It is seen in other embroideries too and might simply be the result of an embroiderer running out of a colour. It might also be that scenes like these were made in advance and then the customer could pick and choose the ones wanted. Note: I cannot prove that each scene was worked separately as the back of the embroidery cannot be inspected. The use of a diaper pattern instead of the 'sunny spirals' might also be a characteristic that is specific for the area of Upper Lusatia/Silesia. - there is gimped couching on the tracery of the architecture above the figures and on elements of the stable behind Mary. - the rim of Mary's halo, the seam of her cloak, the rim of the banner the angel is holding and the rim of Jesus' halo seem to be made from a piece of string that has been wrapped with a gold thread. This wrapped string is then couched down with a silken thread at regular intervals. This is another technique that likely groups some of these embroideries together. - Mary's cloak and Jesus's halo are stitched with two parallel gold threads couched down with silk in a bricking pattern. The design drawing underneath and fragments of silk present hint at further silken details once being present on top of the gold threads. This 'pseudo or nue' seems to be characteristic of 'German' embroideries. - the manger is stitched in burden stitch over a single gold thread. - some elements of Mary's and Joseph's clothing have been edged with two parallel gold threads. These seem to have been couched down at regular intervals with a twisted thread (possibly linen). - Mary's halo is filled with laid flat silk. The silk has been couched down with a single gold thread which has been couched down with the same silk. - the stable roof has received similar treatment, but in this case, two gold threads have been loosely twisted and then couched down with silk forming a zig-zag. - the same twisted thread can be found around the wings of the angel and along the tracery of the architecture. - although most of the silken stitches in the clothing and the fleshy parts of the figures has fallen out, it probably was some sort of long-and-short stitch with flat, untwisted silk. - the triangles above the tracery of the architecture are filled in with laid flat silk and couched down with a trellis of the same silk. There seems to have been an attempt at shading in the laid parts. - the round key-stone in the middle is made of silk and gold thread, but it is difficult to see what is going on exactly. The silk might be radial satin stitch which was then covered with parallel gold threads. - the grassy background is made of laid untwisted flat silk in different shades of green. On top, small flowers were stitched with coloured silks and gold thread. The whole silk embroidery was then couched down with a trellis made with a twisted thread (probably linen). - the hair of the angel and Jesus is made of an over-twisted thread (linen?). - the only other technique present on the chasuble cross is an appliqued piece of silk which forms the headdress of the Mohel (the Jewish cleric responsible for the circumcision). Note: the very fine horizontally spanned threads you might spot in the silken areas are modern conservation threads. If you spot anything else or have corrections on the above, please let me know! When I was looking at this piece in the museum, I exclaimed that it was one of these 'Bridget of Sweden' ones again. My husband contested as he was looking for the typical candle in Joseph's hand in the Nativity scene (our Joseph holds a staff; very common too). When I then started to search for pictures of other pieces on my laptop, I found a very similar chasuble cross in the Diocesan Museum of Bressanone in Italy (check out their virtual tour of the exhibition; also available in English and German!). This chasuble cross has instead of the scene with the Adoration of the Magi, the scene with the Flight into Egypt. Whilst the compositions are identical, the embroidery techniques used may differ. How did this piece end up in Northern Italy? Was it also locally made? This would mean that the geographical area in which identical embroideries were made in the 15th-century was much larger. Were embroideries produced in Lusatia/Silesia export products that were traded to Northern Italy? Or was the piece in Italy acquired through an antiquity dealer who perhaps sold it as an Italian embroidery? Kai Wenzel, the curator from the museum in Görlitz, is going to contact his colleague in Bressanone to see if they have more information on their piece. Update: Unfortunately no further information could be had on the piece in Italy.

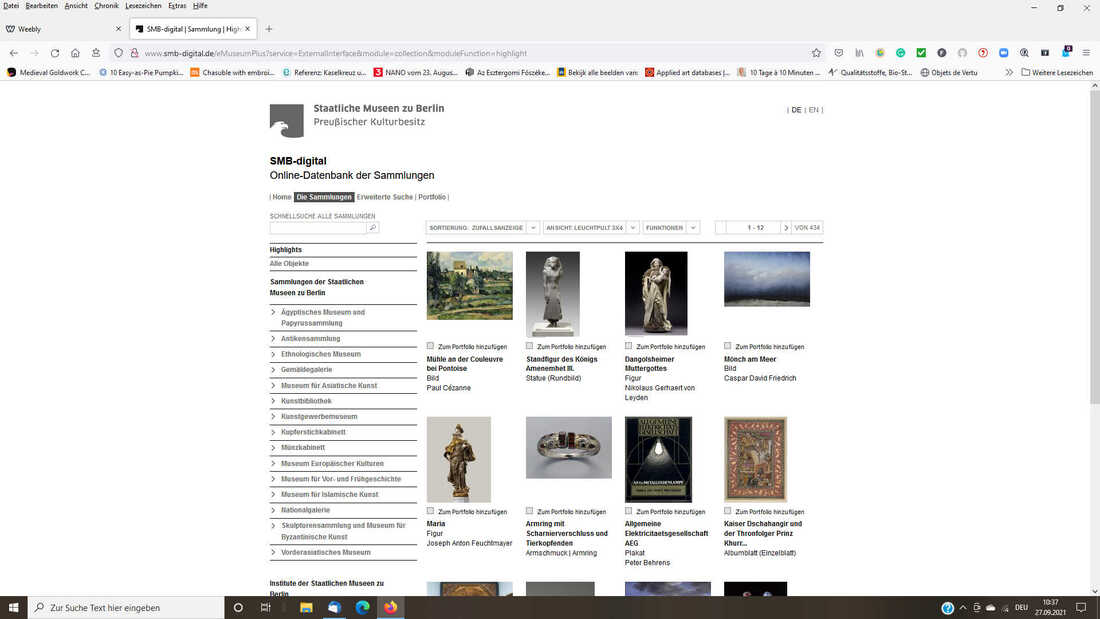

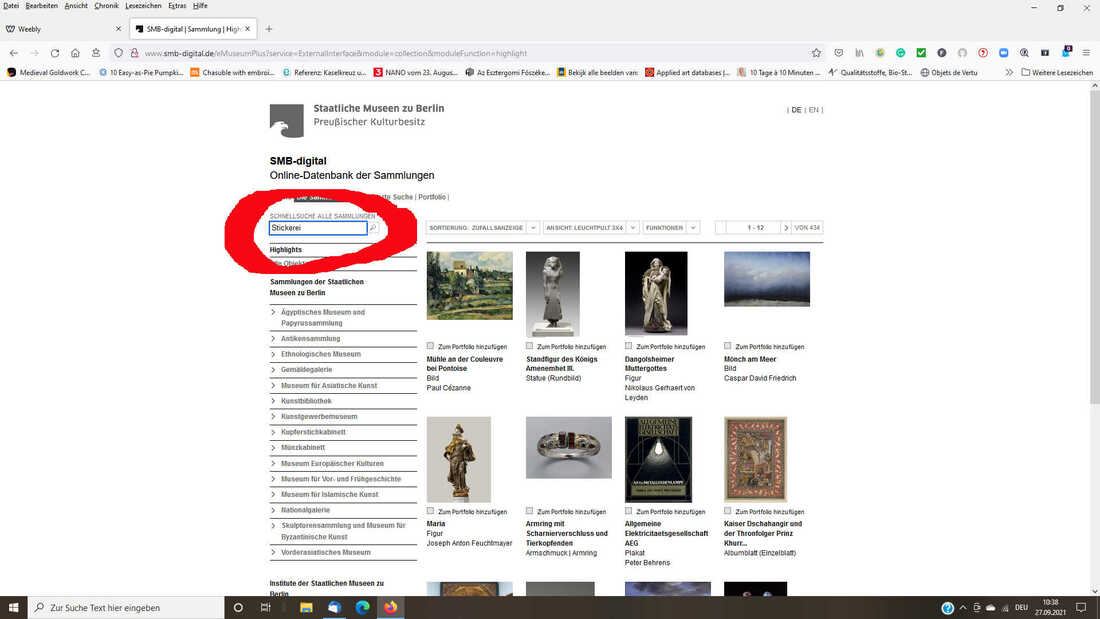

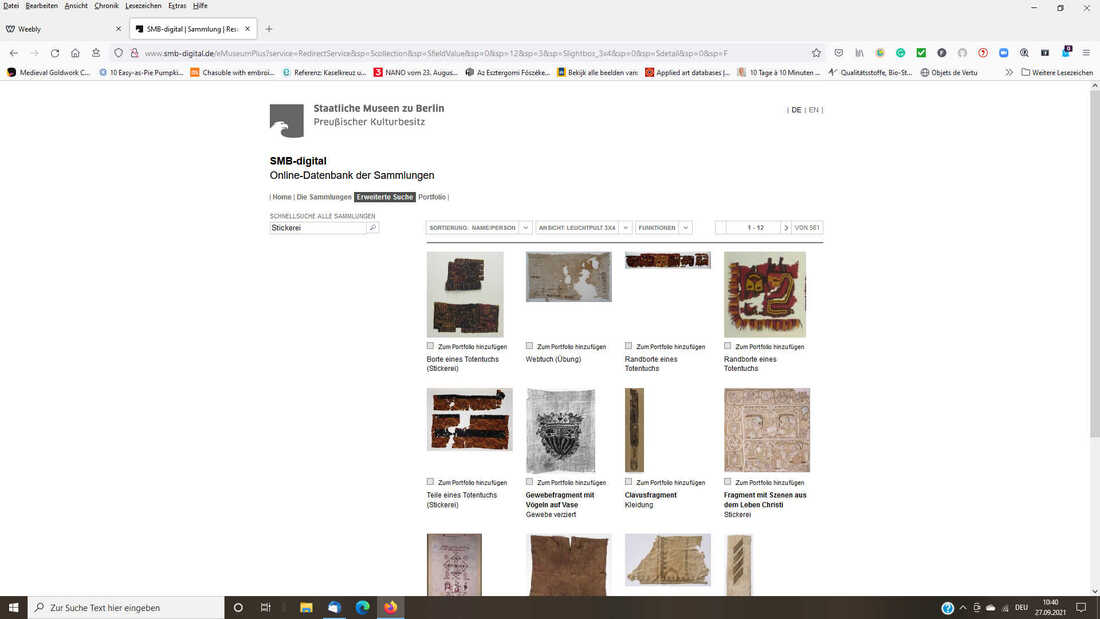

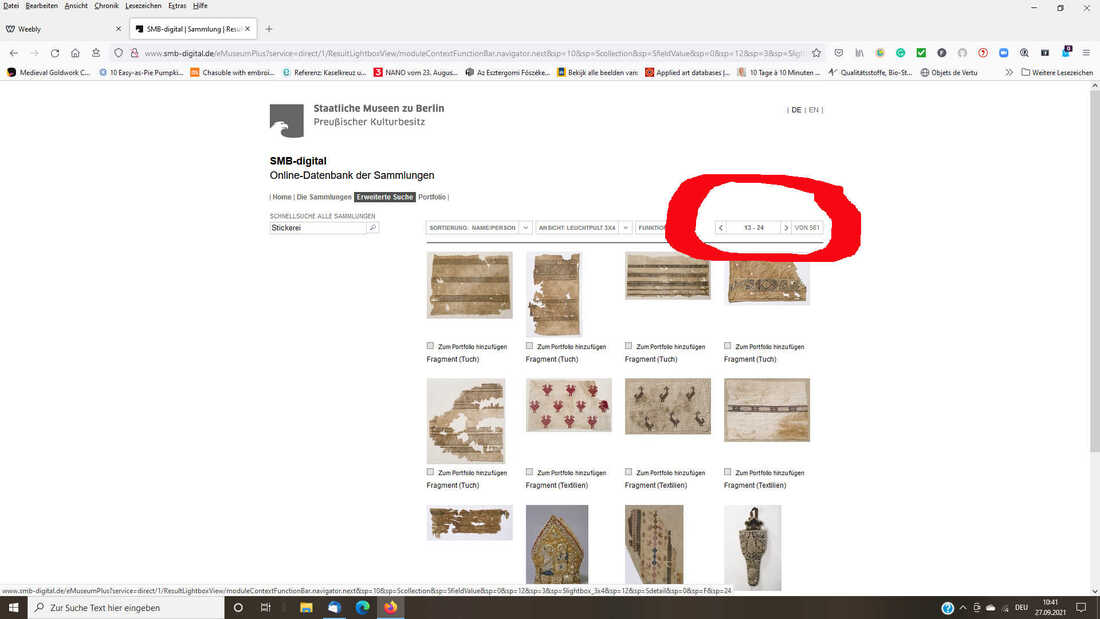

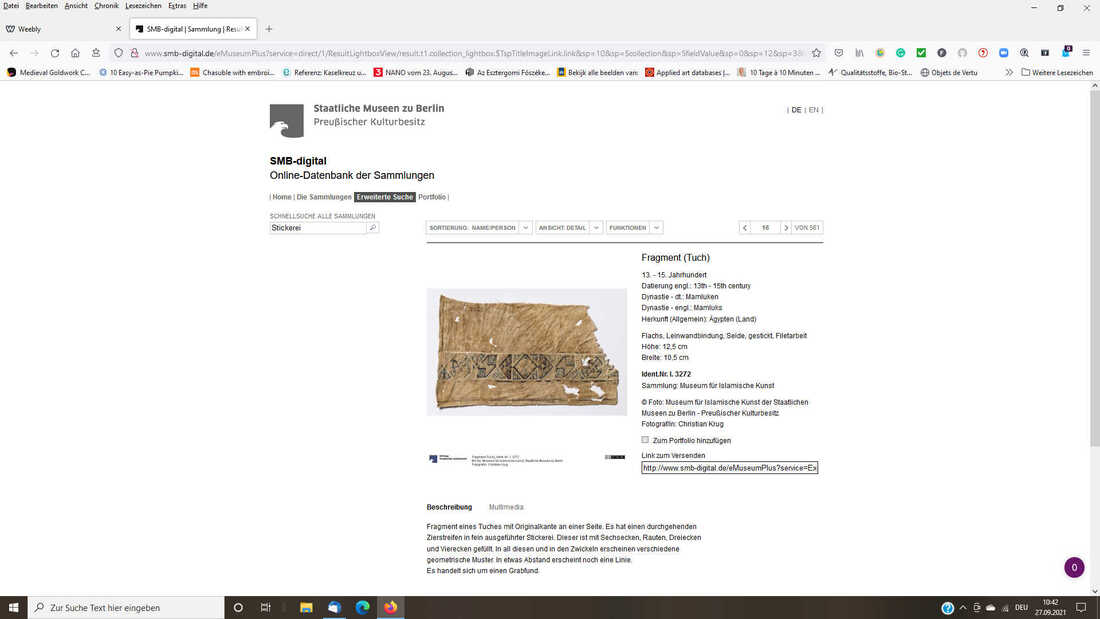

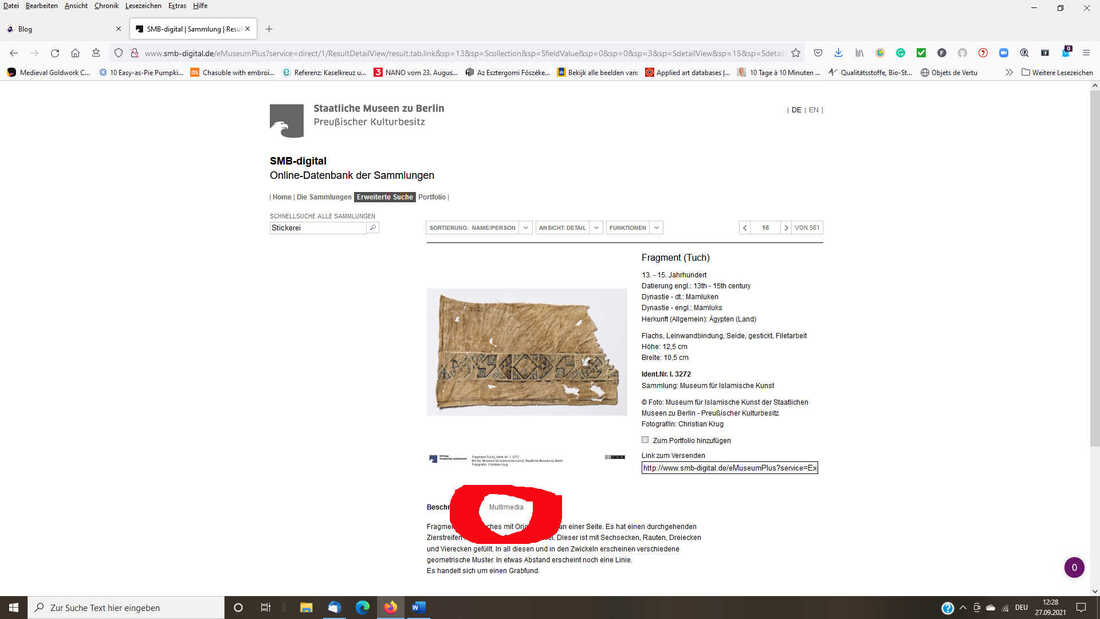

Literature Schellenberg, A., 1927. Schlesische Textilkunst auf der Ausstellung Breslau-Scheitnig 1927. Der Cicerone 19, 477–484. Schellenberg, A., 1928. Mittelalterliche Messgewänder in Schlesien. Jahrbuch des schlesischen Museums für Kunstgewerbe und Altertümer 9, 79–94. Today, I am going to introduce you to a fantastic online museum catalogue: the online collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. You'll have access to the digital collection of the many important museums in Berlin, Germany. And although not all embroidered pieces have been digitized yet, there are hundreds of gems to be discovered. Whether you like whitework or folk embroidery. Although the website can be changed to English, searching in German gets you the better results. So below are a few screenshots of what you should enter where for best results. If you follow the link to the online catalogue, this is what the entry page looks like. Now fill in "Stickerei" in the search box and click the little magnifier. You'll now see the first 12 entries with pictures of a total of 561 embroidered objects in the museum collection. You can use the little arrows to navigate through the many pages with results. Clicking on a picture provides you with detailed information on a particular object. Changing the language to English unfortunately doesn't help. If you click again on the picture it will enlarge. However, if you would like a really good picture with high-resolution, click on the Multimedia tab below the picture and then click on the picture that appears.

Enjoy! Last week, I and my husband visited the Diocesan Museum of St Afra in Augsburg. That's possibly the closest church museum with textiles in relation to where we live, but we had never been there. And that's a shame as it is a charming little museum. Besides ecclesiastical art and historical pieces, you can also see parts of Roman Augsburg below your feet. The excavations have been left open for you to admire. The museum itself is a combination of modern architecture and the historical cathedral cloisters. So what is on display? Quite spectacular are two chasubles dating to the 10th-century. These vestments are associated with bishop Ulrich of Augsburg (AD 890-973). Ulrich lived during turbulent times. He was a friend of Emperor Otto I and successfully defended Augsburg against the marauding Magyars from Hungary. Apparently, he also wrote a treatise on celibacy stating that it was not supported by the bible. All this made Ulrich famous during his lifetime and he became a saint soon after his death. Vestments associated with him became important relics and were held in high esteem. But there was a small problem. Ulrich liked simple clothing. Nothing flashy. His mantle made of local linen was just too plain for the average 12th-century believer. Thus, tiny appliques of silk with goldwork embroidery were added. That's rather cute, don't you think? The museum houses several quite old embroidered textiles. As they need to be displayed at low lighting levels, photographing them is near impossible. However, as I have shown the spectacular embroideries from Bamberg before, I would like to show the above. This small reliquary pouch made of dark purple or blue silk (samite?) with gold embroidery was made in Southern Germany in the 12th-century. Roughly a hundred years later than the pieces on display in Bamberg. But the embroidery technique of couching down very pure goldthreads and hammering them flat is the same. I think the pouch displays two birds (peacocks?) amongst some foliage and maybe a coat of arms. Unfortunately, there was hardly any information on the piece available. The last piece I would like to show is a small reliquary casket. I have never seen anything like it. It looks like an orphrey being glued to a small wooden box. The saint depicted is St Agnes. She is stitched in brick stitch with silks. The background displays a diaper couching pattern; one I haven't seen before. The casket was made in the 13th-century, possibly in Cologne. Quite an unusual piece. And a reminder that embroidery was probably much more widely used. It simply did not survive until the modern-day.

Sadly, this will be my last field trip for a while. Corona numbers are going up in Germany as well. Since I am living in an area with a rather low rate of infections, I don't want to introduce the virus. My husband and I have decided to avoid travelling and gatherings as much as we can until the numbers go down again. Hope you are all safe! P.S. I am being featured in the latest issue of Metier magazine! The article, in Dutch, talks about me and my historically inspired goldwork embroideries. Today I am going to share some more medieval eye-candy with you. This time we are going to explore some of the goldwork embroideries made in France during the 13th-15th centuries. Particularly Paris enjoyed a boom in embroidery during the 13th-14th centuries as the royal court resided there. Written guild regulations from 1292-1295 and 1316 suggest that female embroiderers were the norm and that the apprenticeship lasted eight years. However, the embroiderers attached to the King and the princes have names such as Robert de Varennes or Sandre Lappert. So was the situation in medieval Paris really so different from that in the Low Countries? I doubt it. Prestigious commissions from the French King and his princes were likely given to male embroiderers. The first piece I would like to draw your attention to is a mitre worn by the abbot of the ancient abbey of Sixt, Upper-Savoy. The very fine silk- and gold embroidery is executed on white silk (either samite or serge) backed by linen. The silk embroidery is executed in split stitch and stem stitch. The goldwork embroidery is all done in couching. Although the embroidery was executed by embroiderers from Paris, the drawings were likely made by Jean le Noir, a famous illuminator who had a daughter, called Bourgot, who assisted him. I particularly like how the wings of the angel are placed so that they fit the sloping side of the mitre just perfectly. Another piece that blew my mind was the mitre created for Sainte-Chapelle around 1375-1390. There's so much going on on this relatively small object. And the scenes are adorable. Look at the ox and the ass. They make me smile :). The amount of padding on this piece is rather incredible too. And I just love the tiny seed pearls. It makes it all looks so over the top, yet so coordinated. The treatment of the garments is quite different from the usual or nue or pattern couching seen on so many of these pieces. Instead, the different parts (folds) of the garments are created by laying separate pairs of passing thread in different directions. The folds are accented with couched dark brown silk. Very clever indeed. The last pieces of embroidery I would like to draw your attention to are known as the embroidered cycle of the legend of Saint Martin. This impressive, but incomplete, collection of embroidered orphreys was made for a single altar in a church or chapel. They thus show the medieval opulence when it comes to liturgical vestments. Due to the fact that these pieces were created at the court of Rene of Anjou (1409-1480) we know the painter of some of the designs: Barthelemy d'Eyck and the embroiderer who executed them: Pierre du Billant. It probably helped that both men were related.

The embroidered orphreys are now dispersed over four museums in Paris, Lyon, Baltimore and New York. Their original layout has been lost due to more modern up-cycling. Have a look at the very fine silk shading on the drapery of the clothing on some of the figures (there's definitely more than one embroiderer at work as there are marked differences in quality between the orphreys). The brightness of the colours after nearly 600 years is simply incredible! Literature Descatoire, C., 2019. L'art en broderie au moyen age. Musee de Cluny. ISBN: 978-2-7118-7428-6 . P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! Last week, I and my husband visited the exhibition "L'art en broderie au moyen age" at the Musee Cluny in Paris. The exhibition draws together medieval embroidery from the museum's own collection and from other collections in Europe. Private textile collections from the 19th century (such as the one from Franz Bock) got split up at some point and fragments of the same piece would end up in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Musee Cluny in Paris. It was great to see some happy reunions! I encountered many new to me pieces as well as some 'old friends'. The exhibition was very popular with a wide range of visitors. And there was so much on display that we actually visited twice. Hence, I can't cover it all in one blog post. Today we'll look at the masterpieces from the Germanic lands and the Mosan region (the old Bishopric of Liege). These pieces are characterised by a Romanesque style which still contains many elements of classical art. They have an older feel to them. In addition, these pieces are often completely stitched in coloured silks on linen. One of my favourite pieces of the whole exhibition was the altar cloth or antependium from Mechelen (now part of Belgium). The piece measures 82,5 x 186,5 cm and was made in the early 14th century. The piece depicts four scenes from the Saints lives: Saint Martin healing the infirm, Saint Mark being persecuted during Easter Mass, Saint John sleeping on Christ's lap and Saint John drinking poison in front of Aristodemus of Ephesus. The whole piece consists of counted needlepoint in silks and some gold on a linen background. The different parts of the design are filled with a myriad of counted needlepoint stitches made up of satin stitches. The stitches used for the background give it an embossed appearance. Look at the picture of the face of Saint Mark to see the fineness and the quality of the linen background used for this stunning piece of embroidery. Another stunning piece is this frieze for an antependium made AD 1320-1330 in either the Mosan region or greater Paris. This piece was very hard to photograph due to the way it was displayed. The piece shows scenes from the life of Saint Martin of Tours. You can see him in the second picture sitting on his horse and cutting his mantle in half. The piece is only 19 cm high, but a staggering 256 cm long! The embroidery uses coloured silks and both gold and silver threads. Where the embroidery has worn away, the pattern drawing and the linen padding can be clearly seen. I especially like the treatment of the hair of the figures: very textured with a lot of tiny knots. The third and last piece I like to draw your attention to is a beautiful alms pouch. It is made in the same counted needlepoint technique with silks and gold threads as seen on the antependium from Mechelen. The shine on the silken stitches is unbelievable! This particular purse was made around AD 1300 in either the Mosan region or the Germanic lands. As medieval clothing came without pockets, people wore purses like these to store their money and other belongings such as prayer beads, a book of hours etc. The name 'alms pouch/purse' refers to the common practice of giving alms to the poor as part of your everyday Christian duty. You can find an excellent article on these purses here.

There were many more beautiful pieces on display in this part of the exhibition. For those of you who were not able to visit in person, I can highly recommend the exhibition catalogue. It is packed full with good quality pictures and many close-ups. More on my textile adventures in Paris in further blog posts! Literature Descatoire, C., 2019. L'art en broderie au moyen age. Musee de Cluny. ISBN: 978-2-7118-7428-6. Müller-Christensen, S. & M. Schuette, 1963. Das Stickereiwerk. Wasmuth. No ISBN. Wilckens, L. von, 1991. Die textilen Künste von der Spätantike bis um 1500. Beck. ISBN 3-406-35363-0. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! Two weeks ago, I delivered the Pope to the Clerkenwell Gallery in London for the first-ever exhibition of the Society for Embroidered Work. It was the start of a fantastic, but exhausting week meeting lots of lovely people and seeing some fantastic embroidered pieces. The gallery space itself was wonderful with beautiful lighting and enough room on two levels for all our works to be beautifully exhibited. I did manage to make three videos:

I do apologize for the poor quality, but I hope you get an impression of the huge variety of works on display. Participating artists were: Cat Frampton, Emily Tull, Lou Baker, Edith Barton, Vivienne Beaumont, Rachel Brown, Rebecca Bruton, Stacey Chapman, Nancy Cole, Deborah Cooper, Claire Cooper-Walsh, Elizabeth Griffiths, Sarah Gwyer, Amanda Hartland, Catherine Hicks, Jacqueline Hockley, Sue Hotchkis, Sarah J. Hull, Aran Illingworth, Heidi Ingram, Lina Izan, Anne Kelly, Angela Knapp, Rowena Liley, Anna Liversidge, Marna Lunt, Christina MacDonald, Reena Makwana, Niki McDonald, Ellen Moon, Claire Mort, Lydia Needle, Sue Nicholls, Julia O'Connell, Vicky O'Leary, Frances Palgrave, Sharon Peoples, Yvette Phillips, Imogen Rhodes-Davies, Christine Rollitt, Holly Searle, Arlene Shawcross, Jo Smith, Sue Spence, Bridget Steel-Jessop, Sue Stone, Dionne Swift, Annie Taylor, Olga Teksheva, Kate Tume, Lilach Tzudkevich, Alison Wake, Maria Walker, Helen Walsh, Joan West, Alison Whateley and Holly Yates. A huge thank-you to Cat Frampton and Emily Tull for all their hard work in curating such an incredible exhibition. Those two ladies put in their heart and soul to make it all a success. Let's hope we can pull off an exhibition at regular intervals around the world to promote stitched art as art!

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed