|

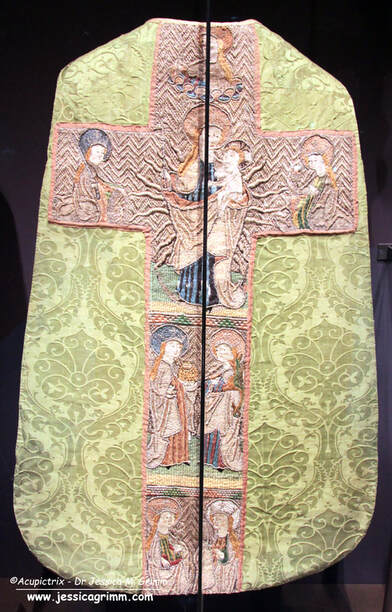

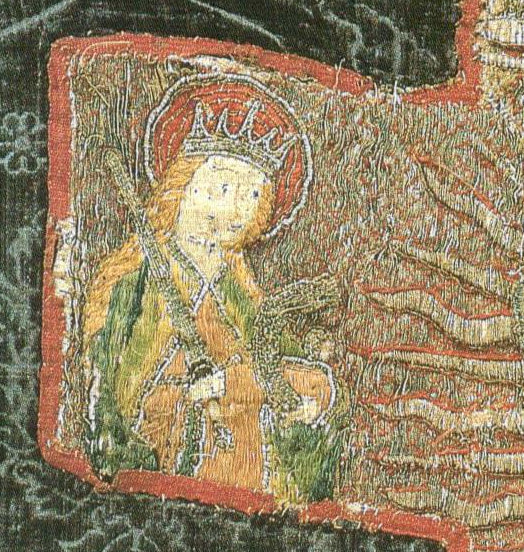

Let's delve into the fascinating world of a unique embroidery crafted around AD 1500 in the Middle Rhine Area. This masterpiece, housed at the Dommuseum Mainz, is a testament to local artistry. Its iconography, a departure from the norm in medieval goldwork embroidery from Europe, is truly one-of-a-kind. It's reminiscent of the whimsical art photographs by Anne Geddes, but instead of babies nestled in foliage, we have the figures of the Crucifixion and an Apostle. Allow me to unveil this intriguing piece. As you can see from the above picture, the embroidered chasuble cross has been cut on all sides. Two patches and an extra piece of grapes have been added on each side of the cross beam of the cross. Those two patches were originally the bottom of one of these foliage cups the figures stand in. It isn't the bottom part of the cup Bartholomew the Apostle stands in (the colours are wrong). This means there either was a further figure below Bartholomew or a column with the same embroidery on the front of the chasuble. I have contacted the museum to see what the front looks like. What is represented here? We see the crucified Christ standing in a foliage cup with two angels catching his blood in chalices. Above Christ, God father is depicted standing in a smaller foliage cup. Below Christ are Saint John and Mary. The crucified Christ, God father, Saint John, Mary and the angels are all familiar figures in a standard Crucifixion scene. Apostle Bartholomew at the bottom is also regularly seen below a Crucifixion scene. What is, however, very unusual is that the Crucifixion scene is embedded in this glorious vine with the beautiful foliage cups and bundles of shaded padded grapes. As far as I know, this particular combination of the vine and the Crucifixion cannot be found on any other piece of medieval goldwork embroidery. It is a unique way of depicting the eucharist. Normally, this is done by showing Jesus working in a wine press. A good example is this silk and metal thread embroidery on linen kept at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg. You see Christ in the Winepress on the left—a very different depiction indeed. But I did find something comparable. Here, you see an icon painted by Angelos Akotantos between AD 1425-1457. It is known as 'Christ the Vine' based on John 15:1–17. We see busts of Christ, the Evangelists and some of the Apostles sitting on the branches of a vine. Could it be that the artists responsible for the chasuble design from Mainz saw an Eastern Orthodox icon of 'Christ the Vine' and combined the idea with the Crucifixion? People, objects and ideas travelled much farther in the Middle Ages than we often think. The actual embroidery is also a bit unusual. The background consists of miles of laid red silk couched with metal threads. The figures and the vine are stitched on linen and then applied to the red and golden background. The vine, and especially the grapes, are heavily padded. The figures are mainly stitched in that typical medieval encroaching satin stitch. And I like the angel's hair. It is probably made of overtwisted silk rather than knots. And in this case, the angel is a partly blonde redhead :).

I hope you liked this unusual piece of medieval goldwork and silk embroidery. The foliage cups are superb design elements one could use in, for instance, a modern crewelwork embroidery.

3 Comments

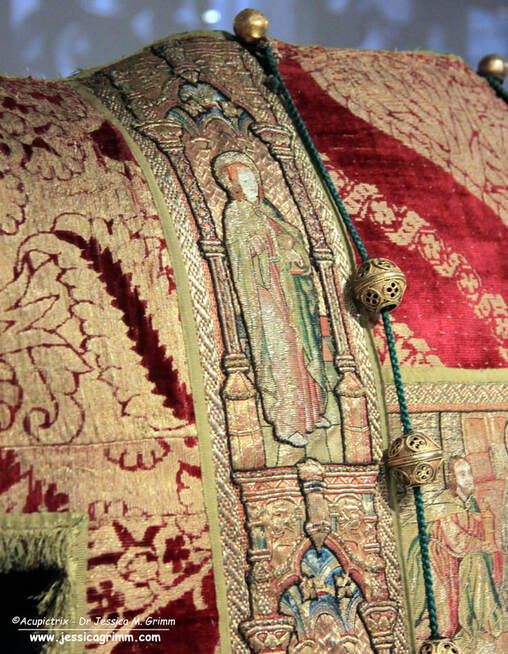

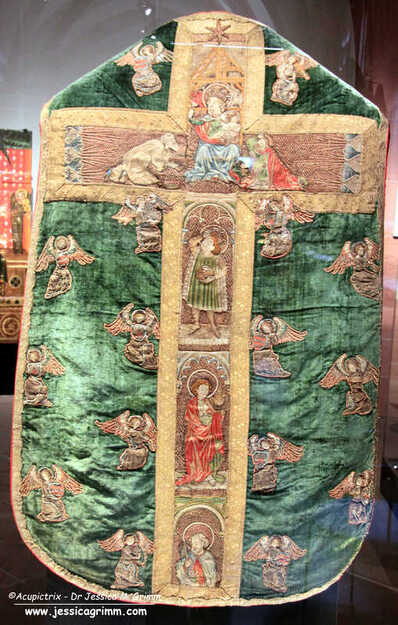

After a successful week of teaching for Creative Experiences in Les Carroz, France, I decided to drive a further 330 km to visit Le-Puy-en-Velay. The Cathedral Treasury houses the Cougard-Fruman textile collection. Judging from the catalogue, the collection comprises of c. 180 pieces. Most of it is liturgical textiles. And a few pieces are medieval goldwork embroidery. The museum is well worth a visit. And even a repeat visit as the pieces on display rotate. The town itself is beautiful too with a medieval 'haute-ville'. It is also one of the main places in France from which to start the Camino pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. But let's have a closer look at one of the embroidered chasubles in the museum. It turned out that I was already somewhat familiar with it ... This is the said chasuble. It was made in Flanders (Brussels?) in the 15th-century according to the museum caption. On the front, we see Catherine of Alexandria above Philip the Apostle (identification uncertain). The cross on the back shows the Trinity at the top flanked by two angels. Below are Saint John and Saint Peter. Although the embroidery does not sport high-quality silk shading or brilliant or nue, the chasuble is a high-end piece. The composition of the Trinity with the two censer swinging angels on either side is balanced and full of movement. The string-padded frame within a string-padded frame for the central depiction of the Trinity also adds extra texture. The lining of the cloaks of the angels is made by couching a piece of blue-green heavy silk in place. The goldwork embroidery is executed with membrane threads. The membrane threads are now badly oxidised and dull. When the embroidery was originally made the threads would have looked golden and shiny. The silk embroidery is done with untwisted silk. I am a bit puzzled by the twisted textile thread used in the padded basket-weave border around the orphrey. It is reddish-brown and much duller than the silks. To me, it looks like wool. However, it might be a thick spun silk. From the pictures in the catalogue, I had not realised that one of the orphreys I bought at an auction is related to the orphreys on this chasuble. When I stood in front of the display case in the museum, it suddenly dawned on me that I had something similar. Luck will have it that I brought the orphrey with me for my students at Les Carroz to study. The museum personnel was very nice and helpful and they allowed me to fetch the orphrey from my car and bring it into the museum for comparison. How cool is that?! As you can see from the above picture of my orphrey, the materials, colours, style of the figure and embroidery techniques are quite similar to that seen on the chasuble in Le Puy. My orphrey is just very dirty and will need some TLC. It was glued onto velvet which was glued onto plywood. As the wood was mouldy, I had to remove the orphrey by cutting through the velvet and glue with a surgical knife. Not a delicate task. But it worked. I will write more on the orphrey and what I did to it in a future blog post.

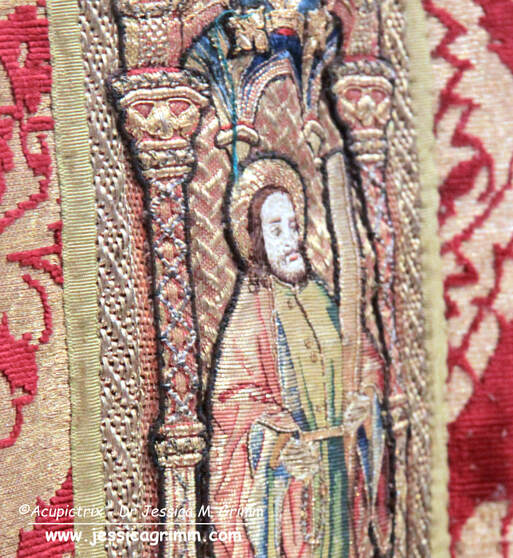

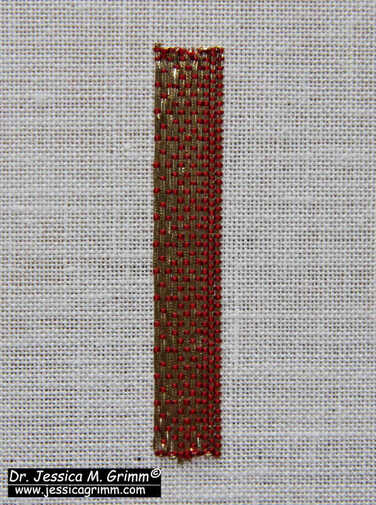

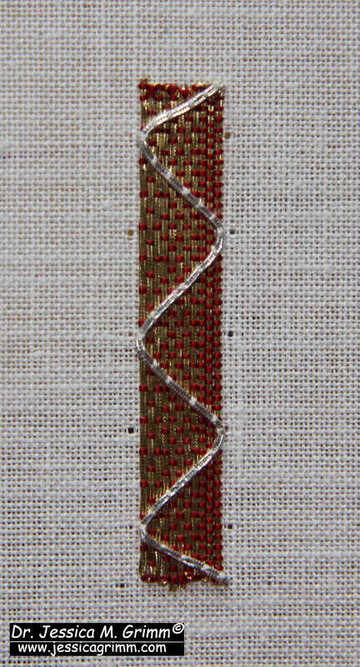

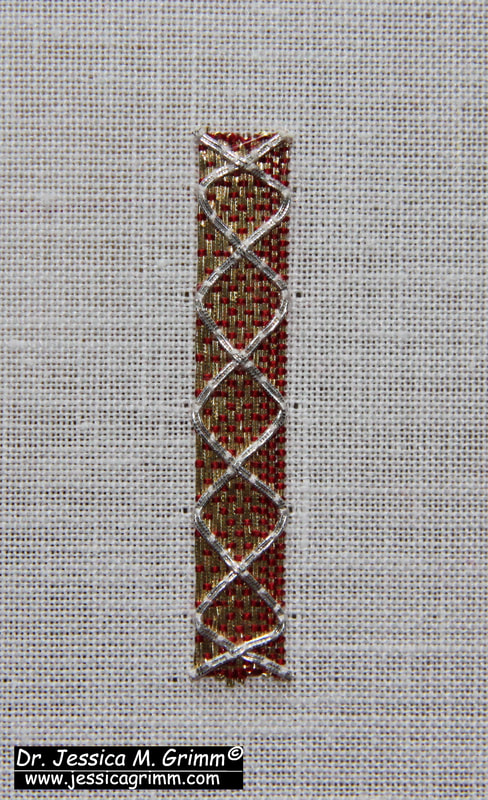

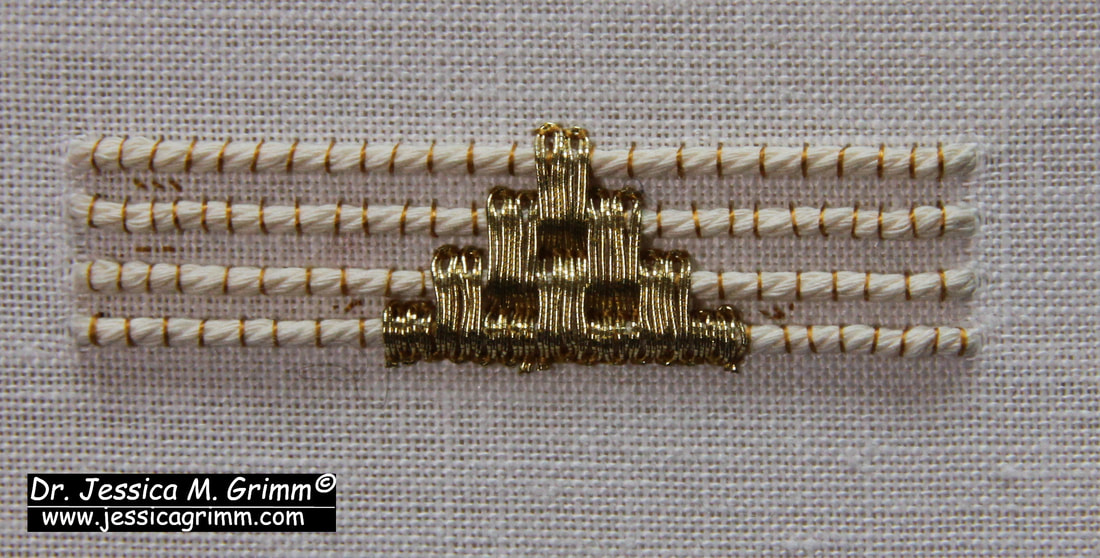

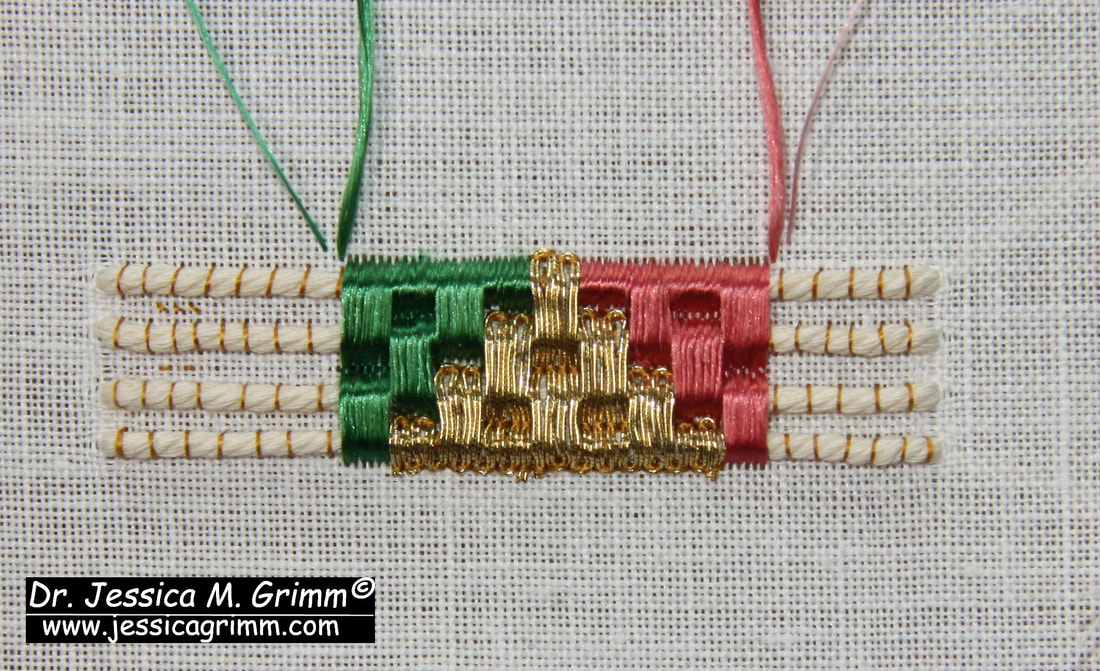

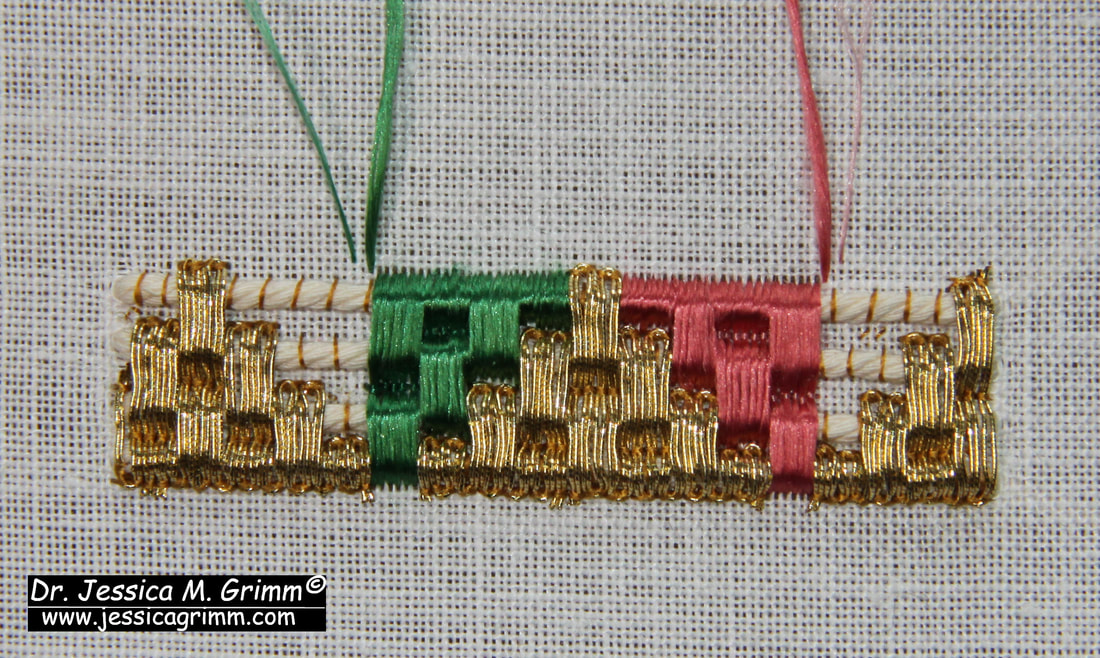

But first, I am off to the International Festival of Gold Embroidery and Jewelery in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Got my flight tickets yesterday and will leave on Wednesday. As I will still be in Uzbekistan next Monday there will be no blog post. As always, my Patrons will be able to follow me on my travels. Literature Cougard-Fruman, J. & D.H. Fruman (2010). Le trésor brodé de la cathédrale du Puy-en-Velay. Centre des Monuments Nationaux. When I started work on this week's stitch tutorial, I had the increasing feeling that things weren't quite what they seemed to be at first. That's the great thing about doing research. I usually have no idea where the medieval embroideries will lead me. Dead ends are common. But so are those 'aha' moments. In this case, it was the latter. Let's dive in! And here is the culprit. No, not Saint Andrew. It is the columns on either side of him. They are odd. The layering of goldwork is a common thing in late-medieval goldwork embroidery. But this is simply too OTT. It does not make sense. Let's start our tutorial proper and I'll point the oddness out to you. Start with a layer of shaded couched goldwork. For my sample (c. 0.8 x 5.0 cm), I used 46ct linen and passing thread #3 couched down with a single ply of red Chinese flat silk. Next up, add the silver passing thread. You will be mainly stitching in between the rows of gold thread of the first layer. However, you will inevitably hit threads of the first layer. Make sure you use a fine needle. A new #12 would be perfect. You might also like to wax your silken couching thread (one ply of grey silk). The "original" embroiderer then went on to add a layer of thicker red stitches along each side of the silver passing thread. I've used a full thread of red Chinese flat silk to do this for the inside of the right-hand side only. By now, I was pretty certain that this was not all done in the late Middle Ages ... So much additional stitching in such a relatively small space is nuts. It does not add anything to the design. On the contrary, you lose quite a bit of the original lovely shading of the first layer. When additional details are stitched in, they usually add to the design. They bling things up or they make the design easier to read by accentuating things. That does not seem to be the case here. So, what's going on? Here's an extreme blown-up detail of that same column. Can you see the thick white/beige couching stitches used to couch down those silver threads? The silver threads themselves are also much thicker than all the other threads used in the embroidery. The added red stitches to the outside of the silver threads are also comparable in thickness to the white/beige stuff. It all looks so much cruder than the original very high-quality stitching done in the medieval period.

As I already told you in my earlier blog posts, these vestments saw extensive restoration in the 1840s. The addition of these silver passing threads on top of the columns was likely done then. It likely serves several purposes. Maybe some columns had so many damaged loose gold threads that this was a decorative way of cleaning things up. But it also does something else. This additional stitching likely goes through many of the layers that these vestments are made of. This stabilizes the whole construction. You often see horrible bulging on non-restored late-medieval vestments. By stitching through multiple layers, you have a chance to make things very stable and secure. It can't really bulge anymore. Is that was what attempted here? What do you think? Do you also feel that not all of the embroidery on these columns is original? My Journeyman and Master Patrons find a downloadable PDF of this tutorial on my Patreon page. After all, working layers of metal thread on top of each other is quite fun to do! One of the highlights of my museum tour at the end of November last year, was the Dommuseum Frankfurt. It has nine medieval embroidered vestments on permanent display. Well worth a visit! At the beginning of the year, I showed you a green chasuble with embroideries from the mid-14th century and the second quarter 15th century made in Cologne. This time, I will introduce you to the Schlosser vestment set with embroideries made in both the Netherlands and Cologne. Both were made around AD 1460. The or nue, or shaded gold, used on the figures is very beautiful. Let's have a look. The Schlosser vestment set consists of a chasuble and two dalmatics. It was bought by Johann Friedrich Heinrich, known as Fritz Schlosser (1780-1851), a councillor from Frankfurt, in 1842/43 from the dealer Fontaine in Cologne. Fritz Schlosser asked his painter friend Edward von Steinle, a vestment maker in Cologne with his two daughters and painter and conservator Johann Anton Ramboux, also in Cologne, to restore the set. Apparently, the vestments were taken apart completely. Loose parts were affixed. But what really astonishes me, is that they treated the new gold threads with acid to make them look old. The vestment maker and his two daughters worked for about a year and were paid a 100 Taler (roughly €4243 today, according to some pretty tricky maths). This was not a living wage when compared to living costs around 1850 in this part of Germany. The vestment maker and his daughters must have had additional income. Thanks to the names and coats of arms embroidered onto the chasuble, we know where it originally came from. The names and coats of arms are of Merten Moench/Maarten Monicx (born in 's-Hertogenbosch (Netherlands), died 1466) councillor in Cologne and his wife Drutgin von den Groeven (died 1451). He probably donated the vestment set to a church in his hometown of 's-Hertogenbosch in 1460. Likely to the chapel of the Fraternity of Our Lady in the St. John's Cathedral. A couple of years later, Maarten also donated the orphreys for a cope. The fraternity had to provide for the fabric and the tailoring of the cope. Unfortunately, the cope has not survived. The curious thing about the embroideries on the Schlosser set of vestments is that they come from two different places. The orphreys on the chasuble were made in Cologne. We see a typical architectural background with saints standing on a tiled floor. However, instead of a golden background, the niche behind the figures consists of horizontally laid blue silk couched down with vertically laid gold. This is a technique not used in the Netherlands. Contrary, the embroideries on the dalmatics were made in the Netherlands. This time, the figures are completely stitched in or nue. The background of the niche in which the saints stand is filled with a basket weave diaper pattern in red. As the original silken stitches of the finely worked faces had fallen out, they were 'restored' with paint. Not sure if this was part of the 1842/43 restoration by the vestment maker of Cologne. Given that there were two accomplished painters in the group of restorers, it would not surprise me if one of them had wielded a brush. By taking a picture under an angle, you can clearly see the different slips that make up the orphreys on the dalmatic. The or nue on the robes of Saint John is absolutely stunning. However, these orphreys are the product of mass production. An identical Saint John can be found on the other dalmatic too. And Saint John isn't the only one. We also have doppelgänger for Saint Paul, Saint Peter, Simon the Zealot, Gregory the Great, James the Great and Saint Andrew. James the Great is even found in the same spot ... And this is only on the front. The backs of the vestments are not really accessible and have not been published either.

Given the fact that Merten Moench was born in what is now the Netherlands and died in what is now Germany, it is probably not that surprising that orphreys from both places were used in this set of vestments. It is likely that the family of Merten moved freely in the area that's now the border between Germany and the Netherlands. What does strike me as odd is that the orphreys of the chasuble on the one hand and the orphreys on the dalmatics on the other hand are quite different. Apparently, this did not matter much to the people who made, gifted and used these vestments in the middle of the 15th century. My Journeyman and Master Patrons find 37 additional pictures of the vestments on my Patreon page. Your monthly contributions made this research possible. Thank you very much! Literature Fircks, Juliane von (2010): Serienproduktion im Medium mittelalterlicher Stickerei - Holzschnitte als Vorlagenmaterial für eine Gruppe mittelrheinischer Kaselkreuze des 15. Jahrhunderts. In: Uta-Christiane Bergemann, Annemarie Stauffer (Eds.): Reiche Bilder. Aspekte zur Produktion und Funktion von Stickereien im Spätmittelalter. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 65–82. Koldeweij, J., Vandenbroeck, P., Vermet, B., 2001. Hieronymus Bosch - das Gesamtwerk: [Katalog]. Belser, Stuttgart. Stolleis, Karen (1992): Der Frankfurter Domschatz: Die Paramente. Liturgische Gewänder und Stickereien 14. bis 20. Jahrhundert. Band I. Frankfurt am Main: Waldemar Kramer. Two weeks ago, we looked at a late 15th century embroidered chasuble kept in the Domschatz of Fritzlar. It had these lovely textured bands or borders between the individual orphreys. The border is made my couching gold threads and coloured silks over string padding. It seems to be a very 'Central European' thing to do. The technique is not difficult at all and would look great in a modern piece of goldwork embroidery or on a piece of needlepoint/canvaswork. So, let me show you how it is done. As always, my Journeyman and Master Patrons can download a practical PDF with all the instructions from my Patreon page. Start by couching down four parallel rows of padding thread or string on your embroidery linen. I am working on a 46ct evenweave. For my couching thread, I used DeVere yarns #6 silk in a gold colour. By looking closely at the original, I could see that the gold threads were applied first followed by the silk. The golden triangles consists of 7 blocks of 4 rows of gold thread. The gold threads are couched down in pairs. I've used a passing thread #3 and the same DeVere yarns gold-coloured silk. Start from the middle. As the border is quite narrow, your gold threads need a lot of manipulation at the turns. Tweezers might come in handy and you might need an extra couching stitch in the turn. As silk is very slippery, I like to go over my couching stitches twice (i.e. place two couching stitches on top of each other). Alternatively, you can wax your silk thread. Remove any exess wax crumbs before you start to stitch. In the original, it becomes clear that the embroiderer went over the turns with their silks when they added the silken triangles. That's how I can see that the gold was stitched first. However, I don't like that as your silk snags so easily on the gold. Instead, I angled my needle under the turns. I've used Au ver a soie ovale with a matching colour DeVere yarns #6 for the couching. Start with only half a silken triangle. Measure the top of the golden triangle and match that for the silken triangles. Add golden triangles before finishing the silken triangles. Your threads will have a tendency to roll off the end of your string padding. In the original, this was solved with a red binding. Very clever indeed. And this is what my finished sample looks like. Wouldn't it be fun to figure out how to turn a 90 degree corner with this technique?

When we looked at the embroidered chasuble from Fritzlar with the Virgo inter Virgines iconography last week, I was sure that I would be able to find many Doppelgänger. I had seen this iconography many times before and I was quite sure that these pieces were all very similar. Nope. They are not. As soon as you start to look at these pieces in more detail you will find that they are all different. Either in the placement of the individual figures and/or in the embroidery techniques used. Now what does this mean? On the one hand, these pieces are readily recognisable as a group and on the other hand, they are all different. This, I think, must mean that there was a late medieval model book that was in use by embroiderers in Central Europe. As no medieval model books used by embroiderers seem to have survived, reconstructing one using actual medieval goldwork embroidery is pretty exciting. Here you see two typical embroidered chasuble crosses showing the Virgo inter Virgines from the late 15th century. The left chasuble was made in Austria in the second half of the 15th century and is kept at the Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts. The piece on the right is part of the private collection of the Bernheimer family. It was made in Southern Germany shortly before AD 1500. In both embroideries, Mary is depicted as the Madonna with child standing on the crescent moon with rays of light behind her. This 'Mondsichelmadonna' was very popular in the 15th century and refers to the Woman of the Apocalypse. On both embroidered chasubles the figures accompanying the Madonna in the large top orphrey are Catherine of Alexandria (with sword) on the left and Saint Barbara (with chalice) on the right. Everything else differs. No angel is crowning Mary on the Bernheimer chasuble. The figures in the two smaller orphreys below the Madonna differ for both embroideries too. On the left, we see Saint Apollonia (?) followed by Saint Ursula. On the right, we see Mary Magdalene followed by Catherine of Siena (?). When we look at the embroidery techniques used, there are differences but also many similarities. For starters, the colours used are very similar. There's mainly blue for Mary and a combination of green and orange for the other virgins. Both embroideries use the same diaper pattern for the golden background: open basket weave. Couched down with a yellow thread for the piece from Austria and couched down with a red thread for the piece from Southern Germany. The treatment of the halos is also identical. There's a layer of silken flat stitches as the base with a couched gold thread on top. The halo is edged with one of these composite threads: a thick textile yarn with a gold thread wound around it. This is sometimes called gold gimp in the German literature. These similarities in both iconography and embroidery techniques show that these pieces are made in the same geographical area. After all, Southern Germany shares a border with Austria. The differences show that the pieces were not made in the same town or guild. Likely, the customer could choose which additional figures to add to the central scene of the Madonna. These additional figures likely had some special meaning for the customer. As the iconography of the Virgo inter Virgines is strongly associated with convents, name days and patron saints of the nuns probably played a role here. And here you see the other main type of the Virgo inter Virgines iconography. The central top orphrey with the Madonna is very similar to that of the two previous examples (Catherine, Ursula, Barbara and Madonna). However, the two smaller orphreys below now show two saints each. We see Dorothea of Caesarea (basket) with Margaret the Virgin (dragon) and Saint Apollonia (thongs with tooth) with Mary Magdalene (ointment box). These two chasuble crosses are identical in their iconography. The treatment of Saint Ursula on a cloud above the Madonna is only seen on these two embroideries as far as I am aware. But there is more. There are other identical embroidery techniques too. See the bands that separate the different orphreys? They are made by couching silk and gold threads over horizontal string padding. And they are identical on both embroidered chasuble crosses. To me, this suggests that both embroideries were made in the same town. Will we ever find out which one? And when we look at the Saint Catherine's of all four embroidered chasuble crosses, they look pretty similar. How did this happen? In the 15th century, ecclesiastical embroidery had already evolved into mass production. Certain scenes were very popular and every self-respecting church wanted them. The 15th century also saw the invention of block book printing (major centres in the South of Germany) and the printing press (invented in Mainz, Central Germany). Likely, cheap block books with simple line drawings of the different Virgins existed in this geographical area too. These would have been used in the embroidery workshops as design inspiration. Designs would have been drawn free-hand or by using a grid to enlarge them more easily. Especially the faces differ between the various versions of a particular figure. This seems to be quite understandable as this is the hardest thing to get right in both drawing and subsequent embroidering.

By consequently digitizing these embroidered figures into line drawings and combining these with the used embroidery techniques, I have a feeling that it should be possible to group them. This hopefully leads to more precise provenances for these embroidered chasuble crosses. It should also help with the identification of incomplete figures on cut orphreys. I am planning to spend my summer holiday learning how to digitize with the help of Inkccape. In the meantime, I am collecting the Virgo inter Virgines embroideries on a Padlet for my Journeyman and Master Patrons to enjoy. Next week, we will work a practical sample based on the above embroideries! Late last year, I visited the Domschatz of Fritzlar. This is a small museum with several embroidered medieval textiles on display, which you can photograph as long as you don't use flash. The textiles are extremely well-lit and very close to the display case's glass. This means that you can examine them very well! The small town of Fritzlar itself is well worth a visit as it has these quintessential charming German medieval townhouses. Today, we will examine one of the embroidered chasubles on display. It was made in the late 15th century in Central Germany. Depending on the defenition, this can comprise parts of Hesse, parts of Franconia, the south of Lower Saxony, Saxony, Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt. As Fritzlar falls within this area, this is thus more or less a local production. Our poor chasuble unfortunately sits right behind the seam of two glass sheets ... The chasuble's iconography is an all-female affair (bar Baby Jesus). The central depiction shows Mary with baby Jesus standing on the moon crescent with rays of light behind them. To Mary's left, the bust of Catherine of Alexandria with sword and wheel. To the right, Saint Barbara with a chalice. Above, on the clouds (i.e. in heaven) sits the bust of Saint Ursula with an arrow. Below this central orphrey, there are two more orphreys with two female saints each. The top one shows Dorothea of Caesarea with a basket and Margaret the Virgin with her pet dragon. Below that is a cut orphrey with Saint Apollonia (thongs) and Mary Magdalene (ointment pot). All the women wear crowns and have a nimbus to identify them as saintly virgins. This concept of the Virgo inter Virgines (the virgin amongst the virgins) originates in Cologne and surrounding Westphalia, Germany. It is seen in various art forms between 1400 and 1530. Although it was popular with a wide range of audiences, it was specifically aimed at religious women in convents. We will examine other examples in next week's blog post. The chasuble has also a corresponding embroidered column on the front. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to see it. Although the embroidery looks a lot cruder than the refined or nue pieces from the Low Countries, it is actually quite high-quality. Many different techniques are being used for both the goldwork and the silk embroidery. For instance, the curley hair of Baby Jesus is made by overtwisting silk and couching it down. The silk embroidery in the faces is mostly vertical shaded brick stitching for the flesh with finely added detailed stitching for the facial features. These are not 'an official type of stitch'. The embroiderer painted with needle and thread to add the eyes, nose and mouth. The folds in the garments have been padded with string padding. The gold threads have been couched over these. Thick silken stitches accentuate these folds further. The rays of light behind Mary have also been padded heavily. But that's not all! Above, you see a detail of Saint Barbara with her tower. If you look closely, just to the left of her nimbus, you can see the string padding that's underneath the diaper pattern of the background. The double chevron pattern is created by couching over horizontally laid string padding. And we see something else that seems to be characteristic of some German embroideries: a thick textile thread wrapped in a thin metal thread. This metal thread is thinner than that used for the rest of the goldwork embroidery. Two of these 'gold gimp' threads are then twisted together and couched down along the edge of the neck opening of the garment and along the edge of the nimbus. I am wondering how they made this thread. Did they put some kind of glue on the thick textile core before they wrapped it tightly with the thin metal thread? I am also thinking that this metal thread is a membrane gold rather than a passing thread. It must be rather 'soft' to accept such tight and uniform coiling around the textile core. I have the suspicion that a passing thread would be too stiff or would show marked bends. Any thoughts? Literature

Weed, S.E., 2002. The Virgo inter virgines: Art and the devotion to virgin saints in the Low Countries and Germany, 1400--1530. Dissertation University of Pennsylvania. Have you seen my new blog index? So far, all blog posts have been neatly indexed. You'll find a list of book reviews, my projects listed according to embroidery techniques, historical embroideries listed according to century and a complete list of all tutorials. Today's tutorial is all about the white string we see in many medieval goldwork embroideries. This padding is often all that remains from the original bead embroidery worked with freshwater pearls. When we are really lucky, a few pearls still adhere. As is the case for the chasuble I showed you two weeks ago. In this tutorial, I will show you how the padding and the beading were worked. I was really surprised by how sturdy this technique actually is. The beaded edge is VERY firm. As always, I worked my sample on a piece of high-count (think 40ct and up) linen stretched on my slate frame. I determined the approximate size of St John's head with nimbus from the original embroidery. It is about 5.3 x 5.9 cm. I made a pricking on transparent paper and transferred the design with pounce powder and ink. As is a favourite with medieval embroiderers, the simple nimbus is actually built up of several layers of embroidery. Start with a layer of radiating satin stitches in blue flat silk. The radiating does not need to be super precise. You can hardly spot the radiating stitches once the next layer of embroidery has been worked. The next layer consists of couched gold thread. Use a fine red silken thread for the couching. Work from the outside in. The first few rows consist of a double gold thread, whilst the last couple of rows consist of a single thread. In the original, the embroiderer would have hidden de turns under the slip of the head of St John. I have turned my threads on the edge of the nimbus. It is now time to add the actual string padding. It is made up of a twisted-together bundle of linen threads. These are couched down with white silk. Start from the middle and retwist your bundle as you go. The ends seem to be tapered in the original. To achieve this, start to cut away pairs of threads from your bundle about a cm before the end. Keep couching and removing pairs of threads until you are left with a single pair on the design line. Sew down the freshwater pearls (Etsy is a good source for these!) onto the string padding using white silk. You might want to wax your thread as the holes of the pearls can be quite rough. Go through each bead twice. In the original, the pearls are sewn down with a little bit of space between them. This was possibly done to save costs. It is said that the string padding was used to elevate the pearls away from the very shiny gold. It also provided a continuous white edging for when the pearls were slightly spaced apart to save on costs. The end result is very stunning!

As always, my Journeymen and Master Patrons find a downloadable PDF of this tutorial on my Patreon page. For as little as €5 per month, you can build your own library of medieval embroidery technique tutorials. Not a bad deal at all! Happy New Year to you all! May it be filled with lots of stitching time and beautifully embroidered eye candy. With the latter, I can help :). My November travels have supplied me with lots of inspiring medieval embroidery from Northwestern Europe that I will share with you in the coming months. I have also acquired two medieval orphreys which we will explore as soon as I have found a box that can house them once they are free of their frames. We will start the new year with an interesting chasuble I encountered at the Dommuseum Frankfurt. The museum is housed in the historical cloisters and is well worth a visit as many medieval vestments are on permanent display and you are allowed to take pictures. From the above pictures, you can tell that this green chasuble contains four different textile adornments: embroidered angels (around AD 1350, Cologne), embroidered chasuble cross (2nd quarter 15th century, Cologne or Middlerhine area), a woven Kölner Borte (mid 15th century, Cologne) and a woven golden border (19th century). When the chasuble changed its shape to the more modern fiddleback form, the textile adornments were simply cut off. The original green chasuble had a much wider shape and was adorned with embroidered musical angels and probably a simple golden forked cross. Probably over time and not all at once, the embroidered chasuble cross, the column made of Kölner Borte and the woven golden border were added. The mid-14th century embroidered angels carry either the coats of arms of the donors or a myriad of musical instruments (fiddle, portative organ, shawm, mandora, psaltery, harp, bagpipes and rebec). The donors have been identified as Cologne merchant and councillor Johann vom Hirtze and his wife Agnes Hardevust. Their son was a priest who donated vestments to a number of his churches. It is even likely that this chasuble is named in his will. The angels are very finely embroidered with 38 parallel gold threads per cm. The gold threads follow the contours of the design. The angels are between 10-12 cm tall and have cotton padding to plump up their faces and bodies. The fact that not the cheaper membrane gold and the expensive (rare and exotic) cotton padding were used, points to a very costly embroidered vestment. The red and blue chenille outlines were added at a later date. Originally, the outlines were made of thick red silk. The angels' hair is made with small embroidered knots in flat silk. The embroidered chasuble cross was made around AD 1425-1449, about 75-100 years later than the musical angels. It has nothing to do with the original donors from Cologne. As there are no comparable pieces, it isn't even certain that it was made in Cologne. The chasuble cross shows the Adoration of the Magi at the top (the scene is cut to fit the new chasuble shape, look at the gifts the Magi hold) and Saint John and Saint Peter below (also cut). The third Magi can be found just below the central scene. The embroidery is exquisite. The gold thread is of high quality, the split stitching is fine and fresh-water pearls were added for extra bling (most have fallen off as the whole rim of the nimb would have been covered too). The gift the Magi is holding is also very interesting. It has shaped spangles that form the tiles on the roof of his house-shaped box. The embroidery of this chasuble cross is thus also very costly. The movement in the figures also points to a high-end designer. Probably a local draftsman and not the embroiderer himself.

That's the first eye candy of the year! Finally, I have been able to finish the new self-paced online course on the embroidery of the 11th-century Wolfgang chasuble. It comes with video instructions and a full kit with real gold thread (this makes up about half of the quoted price; there is no such thing as wholesale when it comes to these small batches of very high-end materials). As always, I make batches of 10 kits and will start to make a new batch when this first one sells out. As there are two designs on the chasuble, a bird and a quadruped, you can either buy a kit for one design or a kit for both designs. You will get the instructions for both. You can also add a medieval transfer kit to your order. The video instructions show you how to use the traditional prick-and-pounce method with iron gall ink. However, you can use the transfer method of your preference too. Literature Stolleis, Karen (1992): Der Frankfurter Domschatz: Die Paramente. Liturgische Gewänder und Stickereien 14. bis 20. Jahrhundert. Band I. Frankfurt am Main: Waldemar Kramer. This is an excellent museum catalogue. Most pictures are in black-and-white, but the descriptions are detailed with lots of literature links. It has been long out of print, but can be found second-hand. Last month, we looked at some early 15th century embroidery from Venice, Italy. You can read about it here: Cope of Pope Gregory XII, further early 15th century embroidery from Venice and a tutorial. This week, we will look at a Venetian piece from the second half of the 15th century. It has some lovely embroidery techniques that would work well for modern goldwork embroidery. And the embroidery background is a bit unusual as well. Instead of using a diaper pattern, it is made of floral motives stitched directly on coloured silk. Let's have a look! I saw the above chasuble at the exhibition in Castello del Buonconsiglio in 2019. The exhibition presented an overview of medieval goldwork embroidery made in Italy; complemented by those pieces that were obtained by trade from Northern Europe. The chasuble is kept, and still being worn once a year!, at the parish church of Azzone, near Bergamo, in the Scalve Valley. The valley came under Venetian rule in 1427 and this probably explains why this piece of Venetian embroidery can be found in Azzone. The chasuble has an embroidered orphrey cross on the front and an embroidered orphrey column on the back. As the figures on the front cannot be identified, the exhibition showed the back. Here we see John the Evangelist at the top, followed by a male martyr with a palm branch and architectural model (According to the literature it is a church. However, it looks more like a castle to me.) and the figure at the bottom is Saint Barbara with her tower. Saint Barbara is the patron saint of miners. The Scalve Valley was famous for its iron ore mines. The embroidery is executed on a layer of silk backed with linen for the background and a layer of linen for the figures. The heads were embroidered separately. The finished orphrey column was stiffened with cardboard. The orphreys measure about 33 x 12 cm. The embroidery is a rather simple, yet very effective, affair. The figures stand on a floor made with laid shaded silk and couched down with a trellis. By having the lighter colour at the front and the darkest colour at the back, the embroiderer created a sense of depth. The undergarment of the martyr is stitched in a similar way. This time, the laid silk is couched down horizontally. The cloak consists of horizontally laid pairs of gold thread which are couched down with white silk. Folds are accentuated with couched coloured silk. The heads are stitched in split stitch.

The treatment of the background behind the figures is quite special. The coloured silken background is part of the design. It is covered with the obligatory arch under which the saint stands. The background is further filled in with tendrils and floral elements. These are made by couching down a pair of gold threads and filling in some elements with shaded satin stitch. The frame around the orphrey consists of a very simple padded basket weave over two padding threads (over three is probably more common). All in all, the embroidery techniques used (laid work instead of brick stitching for the undergarments, simple monochrome couching for the cloaks instead of or nue, embroidered coloured silk for the background instead of a diaper pattern, etc.) are simple and far more speedy to execute than or nue, brick stitching and diaper couching. This likely means that these embroideries were not as expensive as the ones we investigated last month. Literature Prá, Laura Dal; Carmignani, Marina; Peri, Paolo (Eds.) (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Trento: Castello del Buonconsiglio. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed