|

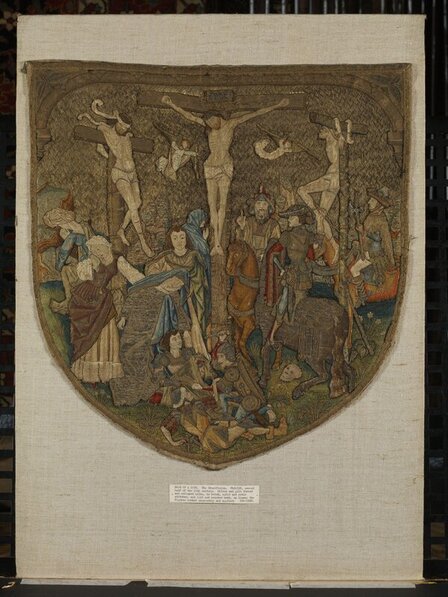

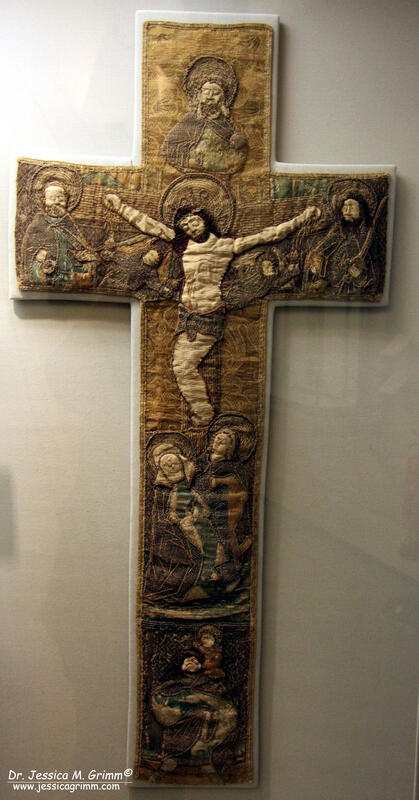

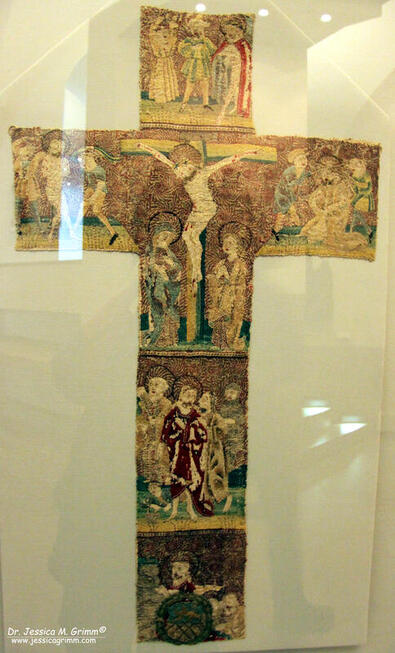

In November 2019, I visited the Clothworkers' Centre in London to study several pieces of embroidery kept in the V&A collection. One of these pieces was a cope hood from Flanders made in the second half of the 15th century (Accession Nr. 990-1888). The piece was bought in 1888 by the museum and lacks any further provenance. Lone cope hoods are pretty common in museum collections. This part of a cope is already relatively loose and could easily be separated before being sold on the art market. Pieces without provenance, like this lone cope hood, always make me a bit sad. So much information was lost. Nevertheless, it is a very fine piece of late-medieval goldwork embroidery. Let's explore! The cope hood measures 53.3 x 51.4 cm and the embroidery fabric is a finely woven linen. Originally, the hood would have been trimmed with some sort of decorative fringe. It likely also had a tassel of some sort dangling from its lowest point. In those areas where the embroidery has fallen out (lower part of the undergarment of the lady with the red dress on the left), a finely shaded underdrawing is visible. Although I am generally not very keen on crucifixion scenes, this one I quite 'like'. There is so much going on. There is so much movement. And there are so many fine details. This is late-medieval art at its best! The design is very high quality and was likely made by a famous artist. Maybe a painter or someone who designed church windows (we know from written sources that they provided embroiderers with designs too). It is highly unlikely that the design stems from an embroiderer who happened to be a fine draftsman too. So, what do we see? And how was it embroidered? We, the viewers, are looking towards Golgotha from under an arch (probably the city gate of Jerusalem as Golgotha was 'outside the city gate' according to Hebrews 13:12). The arch is a far more intricate piece of embroidery than what it looks at first glance. It is partly embroidered as a continuation of the diaper pattern background (capitals on the sides), whilst the gold threads of the rounded arch neatly cover the turns of that same diaper pattern. The silver trefoils in the corners are also very intricately embroidered. There's twist and something that looks like a chain stitch executed with passing thread. On the arch itself, halved quatrefoils are embroidered at regular intervals. Their 'petals' are actually part of the arch. By couching 'petal' outlines onto the arch, the quatrefoils emerge. The diaper pattern used for the background is of the common open basketweave type. The couching stitches were once bright red; the most common colour used. Also part of the background are beautifully stitched rocks. They are embroidered directly onto the background linen. The rocks are made with Burden stitch and use a variety of green and brown silks. On top of this base layer, additional details are stitched with silks and gold thread. The rest of the background consists of a meadow stitched with several shades of green in Burden stitch. At the top, the Burden stitch is worked very densely so that the foundation gold thread can hardly be seen. Towards the bottom, we see the gold thread clearly. On top of the grassy base layer, grasses and several species of plants are stitched with silk and gold. None of the plant shapes is repeated. The flowering plants have different flowers. Maybe the plant lovers in my audience can identify them? Also present in the meadow is a rather funny-looking skull. It has lost most of its embroidery but is still readily identifiable. The skull is a hint to show that we are at Golgotha. According to the bible, Golgotha means 'place of the skull'. And what's with all the people on this piece? They actually tell different parts of the gospels in one very lively scene. Firstly, there are the three crucified people: Jesus in the middle flanked by two criminals. See the body language of those two criminals? The one on the left looks submissive. The one on the right not so much. He even sticks out his tongue. The story of the good thief and the unrepentant thief is told in the gospel of Luke. Interestingly, the crosses of Jesus and the good thief are identical (made of timber), whereas the cross of the unrepentant thief is made of green wood. Has anyone seen this before in embroidery or a painting? Oh, and then there are the two angels with their chalices catching Jesus' blood for the Eucharist.

Next up, are the people on the left. They are on the good side with the good thief. We see four women and a man. The woman on the left with a fancy laced red dress is Mary Magdalene. The woman to her right is Mary mother of Jesus. She is fainting and being caught by Saint John who stands behind her. The two other women in the back are sometimes known as Salome and Mary the wife of Clopas. The bible is vague about these other women. Is this why the designer decided to show them only from the back? On the 'wrong' side are three horsemen. Two are clearly soldiers as they wear weapons. But who is the guy with the strange hat? He points up. What does he want? Is he pointing at Jesus? Is he the centurion who according to the gospel of Mark identifies Jesus as the son of God? Or is he a Jewish priest (as the V&A website suggests)? Any ideas? The last group of figures sits at the bottom of the cross. Three soldiers are dividing Jesus' garment to each have a piece. This is also a well-known story from the gospels. Whoever drew the design for this cope hood was very well acquainted with the biblical stories. Far more so than most people are today. How are all these different figures stitched? None of them are stitched directly onto the background linen. Instead, single figures or a group of figures are stitched on a separate piece of linen and then appliqued onto the background. This creates a little bit of depth in the embroidery. Can you see some of the crude white tacking stitches along the edges of parts of some of these figures? These are later repairs. It never ceases to amaze me that people repaired these very high-class embroideries with such crude stitching in later times! Have a good look at the embroidery of the figures. You will see beautiful or nue in the clothing of some of the figures, on the crosses and on the horse. There is also beautifully shaded medieval long and short stitch (it is more a counted thread technique than our modern version of long and short). The use of both gold and silver thread further enhances the design. The quality of the embroidery matches the quality of the design. This would once have been a very expensive piece of embroidery. It was probably commissioned by an important church or important church leader. Think cathedral or bishop. If we only knew for which church it was originally intended. Or who designed or stitched it!

4 Comments

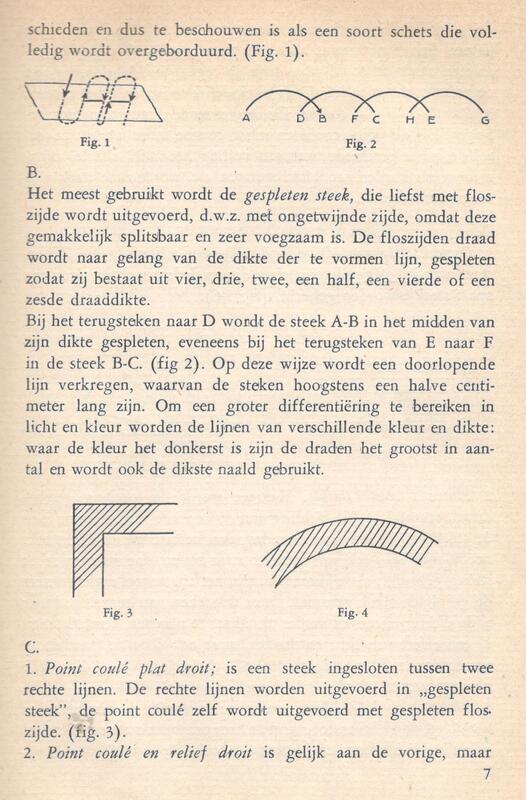

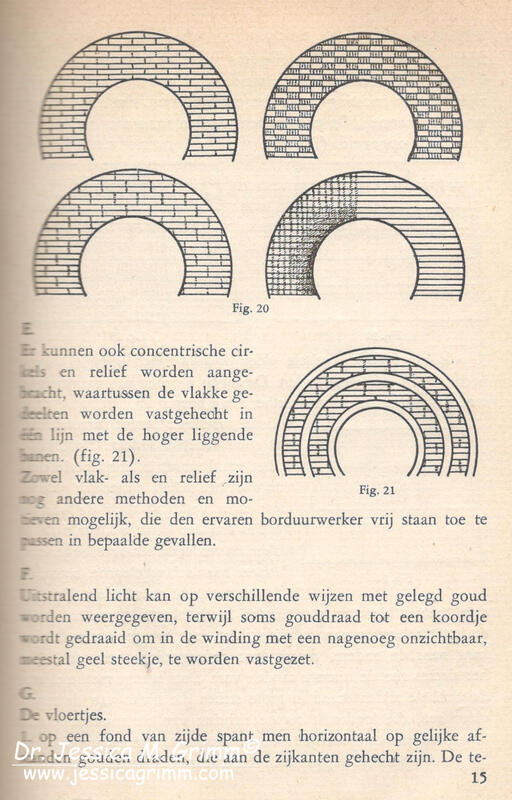

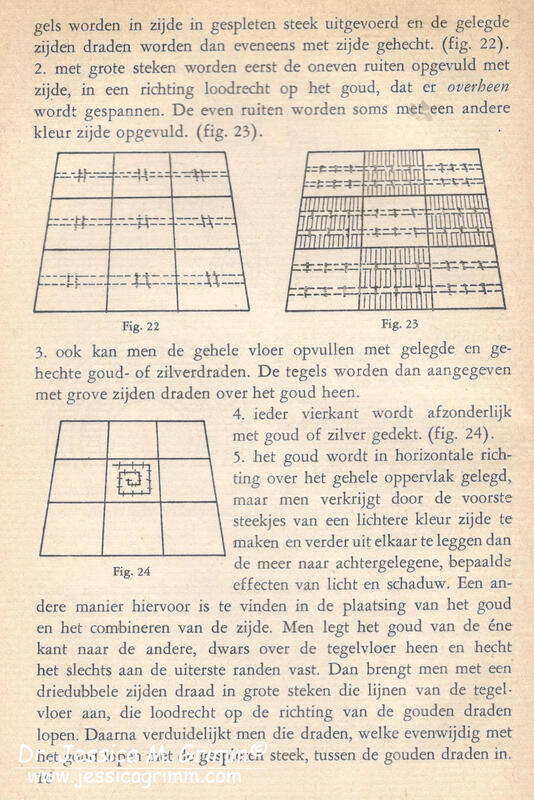

This might not come as a surprise to you: I love books on embroidery! Not only the so-called project books or books on a particular technique, but also museum catalogues and research papers. Whilst the first are usually promoted by and within the embroidery community, the later are a little harder to find. Second-hand bookshops are a good place to look for them. Since the topic is such a specific one, the people in the bookshop can often tell you in an instant if they carry some. Recently I rediscovered one such book in my extensive library. It is a Dutch doctoral thesis from 1948 written by Dr. Beatrice Jansen (1914-2008). The title of the thesis defended at the University of Utrecht is: Laat gotisch borduurwerk in Nederland (Late Gothic embroideries from the Netherlands). I bought the book years ago as I liked the technical and design drawings, but I had never actually read it ... Until now. And it actually is a gem! Let's explore together ... The first chapter concerns itself with the embroidery techniques used. Dr. Jansen was probably not an embroiderer, but certainly a true art-historian. Back in the late 1940s, art-historians used French and German sources for their research. Dr. Jansen copied the French names of embroidery techniques from 'La broderie du XIe siecle jusqu' a nos jours' from L. de Farcy printed in Paris, 1892. You can find an online digitised copy of the catalogue and all the black-and-white photographs here. Although these are truly lovely, I would rather have had a digital copy of the chapter with the embroidery techniques explained. It is quite difficult to understand what Dr. Jansen is talking about. The other source used is a German one: 'Künstlerische Entwicklung der Weberei und Stickerei' by M. Dreger written in 1904. This book can also be viewed online. However, this is only the text. They didn't digitize the plates ... Both books are still around and can be purchased from book dealers. However, they sell for hundreds (till thousands!) of euros. So I probably go to the library in Munich :). That said; when Dr. Jansen really dives into the embroidery seen on the Dutch liturgical vestments, she does present a lot of rather lovely technical drawings. And that's the true merit of this book. The next chapter is a lovely one too! Dr. Jansen presents all the historical sources concerning medieval embroiderers or acupictores as they were called. The female form, acupictrix was rare and only used as 'wife-of'. Indeed, professional embroidery was a male occupation and females only seemed to have contributed in the ateliers of their husbands (and maybe fathers). What is also interesting, the embroiderers did not have a guild of their own. They were usually part of the guild of the painters as they were seen as 'painters with thread'. The embroiderers did not only stitch new vestments; they are explicitly required to mend existing ones as well. And, this doesn't really come as a surprise: the job wasn't well paid and did not have the same standing as that of artisans working in the 'high arts' like painters and sculptures. Discrimination against textile art certainly has deep roots! The next two chapters try to divide the gothic vestments into a group made in the Northern Netherlands (roughly present-day Netherlands) and a Southern group (roughly present-day Belgium). These chapters are pure art-historian. Due to the fact that this book is so old, not all pieces talked about are represented by a black-and-white photograph in the catalogue. But lo-and-behold, I own a modern catalogue from the exhibition in the Catharijne Convent in 2015! So I wrote the modern catalogue number and, if applicable, the inventory number into the margins for quicker reference. Even before the publication of Dr. Jansen, art-historians have tried to name the artists who made the design for these vestments. Successful matches could be made with paintings, woodcuts and sculptures of which the names of the artists have survived. It becomes evident that prints circulated in the embroidery ateliers after which the embroidery was executed. Clients would have had very specific ideas about what they wanted on their vestments and in which style. Chapter V tries to further categorize the vestments by looking at the embroidered architecture. When you start looking at these vestments, you soon realize that certain elements of the architecture are very similar between different pieces. This chapter is richly illustrated with line drawings of all the different architectural styles found on the orphreys of the vestments. Chapter VI high-lights that these kind of embroideries were made at least a century earlier than the pieces that have survived in modern-day museum collections. The oldest painting depicting this type of embroidery is the Ghent Altarpiece made by Hubert and Jan van Eyck between 1427 and 1432. This chapter lists nearly 60 other paintings depicting this type of embroidery. The thesis concludes with a sammery in Dutch and English. I also found a rather embarrassing remark in the margin made by a previous owner. It reads 'Hier had ik nu eens graag gehoord, welke mof dit woord invoerde en welke hollander dit germanisme' (I would have loved to hear which mof (= Nazi) introduced this word and which Dutchman came up with this germanism). Remember, this book was published only three years after the end of the Second World War ...

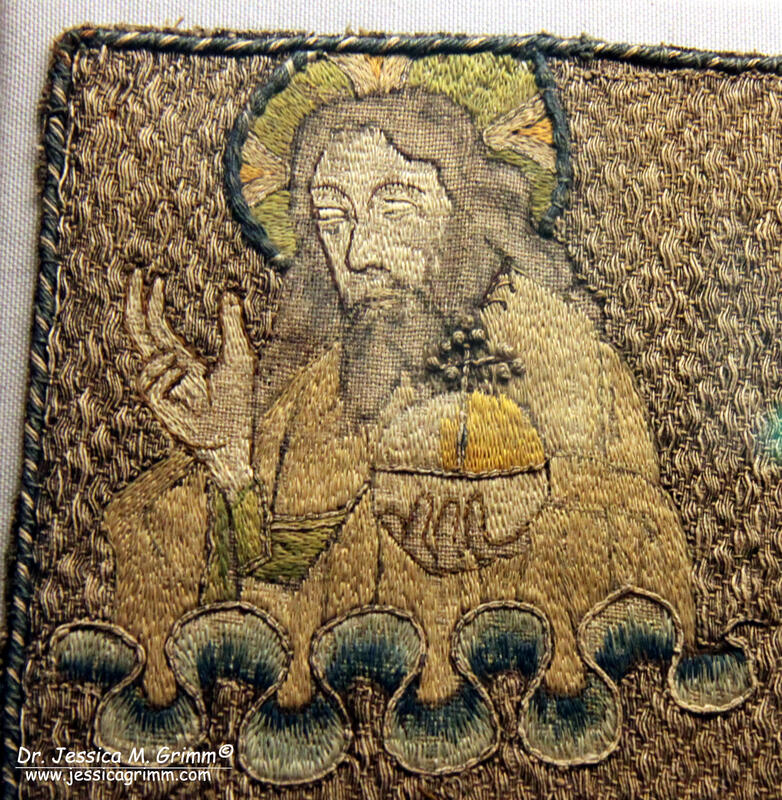

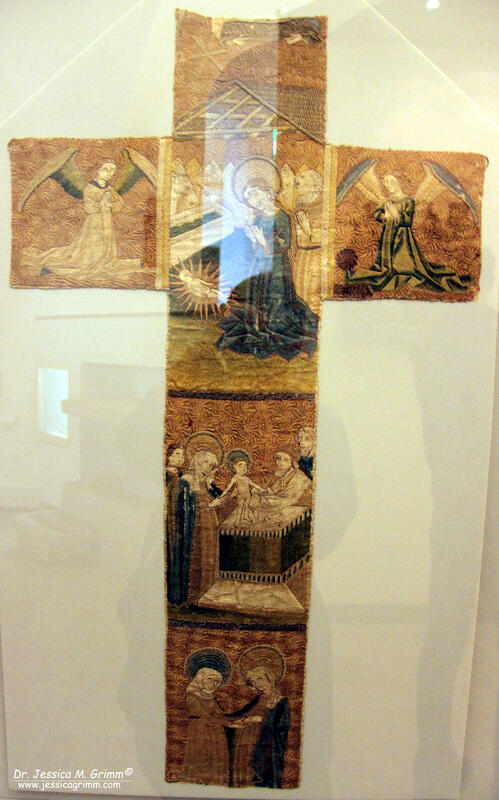

Since this book was published so long ago, you can only find it in libraries (all over the world as it is a doctoral thesis!) or second-hand. Unfortunately, only more modern theses are available online from the University of Utrecht. And since the author died only 11 years ago, it will take another 59 years before the book can be digitised by me and put into the public domain :). I can probably just manage that before turning 100! Last week, I showed you the vestments from the 17th and 18th century on display at the Dommuseum in Fulda. This week we will have a look at the medieval ones. Although the lighting was much better in this part of the exhibition, the glass of the showcases posed a huge problem when photographing the pieces. And to make matters worse, the warden revoked my permission to photograph. Nevertheless, I have a hand-full of nice pictures of very high-end goldwork and silk embroidery to share with you! First up are two pictures of an embroidered cross which would have adorned a chasuble. These embroideries were so precious, that they were mostly re-used on a new vestment when the old one was worn. In this case, the embroidery is a little special: it is raised embroidery. We often associate stumpwork embroidery with 17th-century England. In this case, however, the embroidery was done around 1500. The exact provenance was not stated, but these stumpwork embroideries were all made in the German-speaking parts of Europe. The most exquisite examples can be found in Mariazell, Austria. Here the figures stand about 3 cm proud of the background fabric! In the detail picture above, one can clearly see that the faces of both Peter and Jesus are padded. Jesus's ribcage is defined with a piece of string padding. The whole figure of Jesus seems to be somewhat padded. And the flesh-coloured fabric looks quite stiff and a bit like paper or vellum. And here we have two depictures of God from two different late-medieval chasuble crosses. Unfortunately, no further information was displayed for these two. Or maybe I forgot to take a picture ... I quite like these two. The clouds remind me somewhat of Chinese embroidery on the imperial Dragon Robes. Last up are these two. They are chasuble crosses embroidered around 1480. No provenance is given. These two caught my eye as the embroidery techniques used are quite different from the other vestments on display. No or nue here; the figures are stitched in silk using long-and-short stitch. In this detail shot, you can see what I mean. No or nue for the figures here. Instead, there is meticulous tapestry shading on the clothing (i.e. silk shading strict vertically instead of naturally). And the couching patterns for the goldwork threads in the background are so full of movement and quite different from the strict geometrical patterns seen in the late-medieval vestments from the Low Countries. I had a strange feeling that I had seen this before. And luckily for me, my mind sometimes does a good job :). Instead of needing to go through my thousands of pictures taken at museums, I knew at which museum I had seen this: the Diözesanmuseum Brixen, Italy. This late-15th-century (same date as the one from Fulda!) chasuble cross has a similar couched background. And most of the figures are stitched in tapestry shading rather than or nue (Mary being a notable exemption). So maybe the chasuble cross held at the Dommuseum Fulda has a more southern origin?

Being able to make these connections only works when I am allowed to take pictures. As lighting conditions or the way things are exhibited often do not permit studying the embroidery with the naked eye, my pictures are a great help. The camera is able to pick up details even when lighting is poor. I can zoom while taking a picture and again when looking at my pictures on the computer. Applying filters will tell me even more about the way things were made. It is therefore always very sad when the taking of pictures is not permitted. As long as you do not use flash (or use another source of light such as your phone!), you are not damaging the exhibits. And me taking pictures of the exhibits as is, has other benefits too. I don't need to make an official appointment for which museum staff needs to 'host' me (they have better things to do) and I don't need to handle the exhibits either. Some museums argue that by taking photographs and publishing them in a blog or on social media will mean fewer people will actually visit the museum. Really? I have the sneaking feeling that more people will visit a museum when they know what is on show. Especially museums with a wide range of exhibits of which textiles are only a small portion. The museum's website often does not specifically state that there are gorgeous embroideries on display (they are a somewhat neglected category, especially when in competition with bling made of precious metals) which might interest the curious embroiderer. And I know that several of my readers have visited museums which featured in my blogs. I have been guilty of doing the same. Maybe we should start mentioning these things to staff on duty when visiting a museum after reading a blog or seeing a picture on social media. What do you think? A couple of weeks ago, I visited the Dommuseum in Fulda. I knew from their website that they had at least some embroidered vestments. Little did I know that they had quite a lot of them! And when I asked if I would be allowed to take pictures, the clerk on duty said that he didn't mind me taking pictures. Unfortunately, he was quite a character and rather unpleasant. Half-way through the exhibition, he told me to stop photographing. No reason was given. Lucky for you and me, I had been able to take quite a few pictures before I was told to stop :). Enjoy the bling ... The above short video was shot with my phone. What you see here is one of the rooms where the vestments are shown. There are several of these large displays. They are reserved for the 'younger' vestments dating to the Baroque and Rococo (17th and 18th century). The vestments are shown in a kind of altar setting interspersed with other liturgical objects. Sets of matching liturgical vestments (cope, chasuble and dalmatic) are grouped together. As you can see the lighting is rather sparse. And the fact that most pieces are placed at a distance from the glass wall, makes studying them almost impossible. The written information was mostly limited to the name of the vestment, the date and the person who paid for it or for whom it was made. Not ideal for the curious embroideress! That said: the dim light and the 'scenic' placement of the vestments did give a good idea of how these gold embroidered vestements would have sparkled all those centuries ago. And that is an impression not many of us get to see nowadays. After all, how likely would it be to sit in a church service in the semi-dark (safety hazard!) with enough senior clergymen present (they are thinly spread these days!) that a full set of these antique vestments (museum people in uproar!) can be worn? And this is a picture of the same display made with my Canon digital camera (no flash, just a very steady hand). On the far left, you'll see a yellow cope behind a yellow dalmatic and maniple. They belong to the so-called Harstallscher Goldornat made in 1802 for the last Prince-Bishop of Fulda Adalbert von Harstall (1737-1814). The vestments are made of silk and gold brocade with some goldwork embroidery. Prominently in the middle of the picture are some red vestments. From the left: chasuble, stola, cope, palla, bursa, pink chasuble, pink stola and dalmatic. They belong to the so-called Roter Schleiffrasornat made in 1702 for Prince-Bishop Adalbert von Schleiffras (1650-1714). It is the oldest complete set of vestments in the museum. The vestments are made of silk and heavily decorated with goldwork embroidery. Detail of the cope hood of the Roter Schleiffrasornat. And this exquisite piece of goldwork embroidery can be found on the hood of the cope belonging to the Weisser Buseckscher Ornat made in 1748 for the Prince-Bishop Amand von Buseck (1685-1756). The fact that Amand was very good at drawing and a sponsor of the arts is probably reflected in the high quality of the padded goldwork on his vestments. Amongst all the bling I discovered what looks like a 17th-century casket of some sorts. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't take decent pictures of it. And there was no information on the piece either. But since I know that there are several 'casketeers' reading my blog, I am including it here anyway.

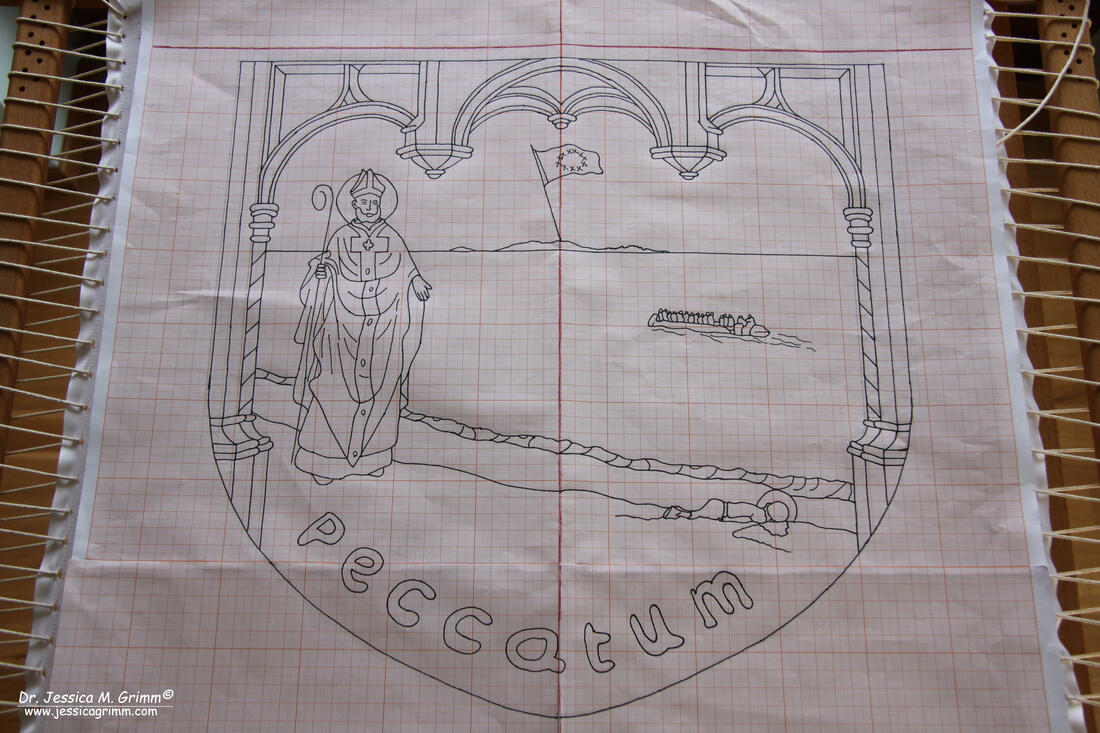

That's quite enough bling for today me thinks! Although it is quite difficult to see the beautiful goldwork embroidery up close due to the way the pieces are presented, the museum is well worth a visit and even a detour when you are in the area. Especially as they have some even greater embroidered treasures dating to the Middle Ages. But that's for another blog post ... When I was still working on Pope Francis, I already had the idea for my next piece in my head. After a bit of research, I have made the drawings and transferred the pattern onto 40ct Zweigart natural linen. As the piece is quite big, I had to use a window to do the pattern transfer. And even then it only just fit. So what is it going to be? I am sort of working on a series using the religious goldwork produced in the first half of the 16th century as my inspiration. After two orphreys (St. Laurence and Pope Francis) I needed a bigger canvas for the next story I wanted to tell. So I am going for the shield of a cope or pluviale in Latin. This type of garment may be worn by all ranks of clergy during processions. It is modelled on the late Roman raincoat. The now decorative shield was originally a hood. For me, the migration crisis of 2015 has left some powerful images in my head. There were these family fathers on Munich main station looking so stressed when trying to keep their wife and children safe. I immediately wondered how well my own father would cope with us at the central train station in Damascus. He is good with keeping an eye on us, but his Arabic is rather poor... Furthermore, I and my husband travelled amongst refugee families when coming from Vienna. When I confirmed that we had crossed the German border some refugees started to praise God. But the most powerful picture of them all has been that of the little Syrian boy Alan Kurdi washed up on a beach in Turkey. Whatever your views on immigration, a drowned two-year-old war victim is a shame on us all. That's why the Latin word for 'sin' is written in the sand. My cope shield shows how Saint Nicholas finds the body of Alan on the beach. Saint Nicholas was bishop of Myra, in Turkey, in the early fourth century. He happens to be the patron saint of sailors. Also on my cope shield is the silhouette of the Greek island of Kos. Alan and his family were trying to reach Kos when their inflatable boat capsized and many drowned. The body of Alan's mother and brother also washed ashore. When researching for the piece, I found out that the family had tried to officially immigrate to Canada as they already had family there. Fulfilling all the bureaucratic requirements proved impossible and so the application was denied. This sad story has a lot of similarities to the heart-breaking stories of Jews who tried to migrate out of Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

So what am I planning to do embroidery-wise? The dome and columns framing the piece are going to be couched goldwork. The figures of St Nick and Alan Kurdi will be done in or nue. For the fast background of sand, sea and sky I will be using classical canvas filling stitches. Especially for the later, I am hoping to use fairtrade hand-dyed silks by House of Embroidery. Poverty and hopelessness, now increasingly the result of climate change, are the underlying factors of conflict and migration. Let's combat this one stitch at a time! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed