|

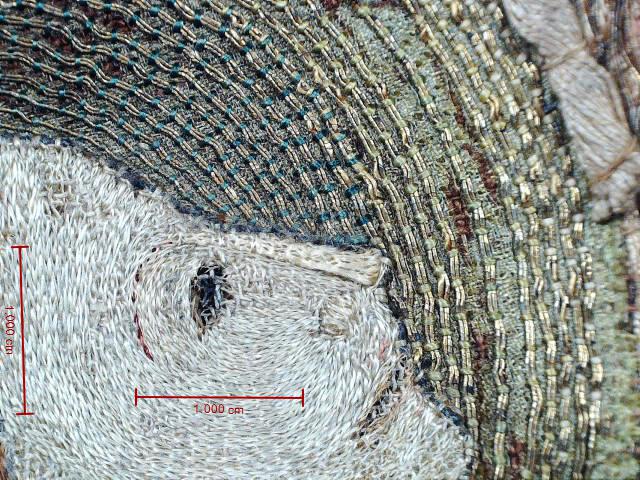

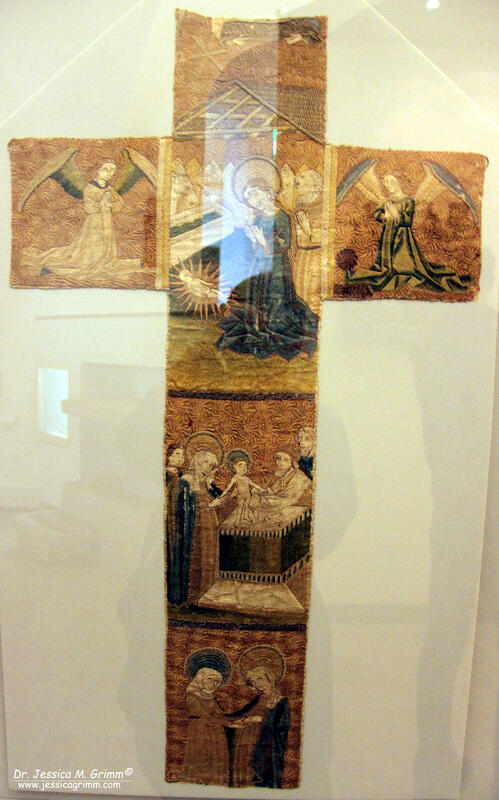

Late last year, I visited the Domschatz of Fritzlar. This is a small museum with several embroidered medieval textiles on display, which you can photograph as long as you don't use flash. The textiles are extremely well-lit and very close to the display case's glass. This means that you can examine them very well! The small town of Fritzlar itself is well worth a visit as it has these quintessential charming German medieval townhouses. Today, we will examine one of the embroidered chasubles on display. It was made in the late 15th century in Central Germany. Depending on the defenition, this can comprise parts of Hesse, parts of Franconia, the south of Lower Saxony, Saxony, Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt. As Fritzlar falls within this area, this is thus more or less a local production. Our poor chasuble unfortunately sits right behind the seam of two glass sheets ... The chasuble's iconography is an all-female affair (bar Baby Jesus). The central depiction shows Mary with baby Jesus standing on the moon crescent with rays of light behind them. To Mary's left, the bust of Catherine of Alexandria with sword and wheel. To the right, Saint Barbara with a chalice. Above, on the clouds (i.e. in heaven) sits the bust of Saint Ursula with an arrow. Below this central orphrey, there are two more orphreys with two female saints each. The top one shows Dorothea of Caesarea with a basket and Margaret the Virgin with her pet dragon. Below that is a cut orphrey with Saint Apollonia (thongs) and Mary Magdalene (ointment pot). All the women wear crowns and have a nimbus to identify them as saintly virgins. This concept of the Virgo inter Virgines (the virgin amongst the virgins) originates in Cologne and surrounding Westphalia, Germany. It is seen in various art forms between 1400 and 1530. Although it was popular with a wide range of audiences, it was specifically aimed at religious women in convents. We will examine other examples in next week's blog post. The chasuble has also a corresponding embroidered column on the front. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to see it. Although the embroidery looks a lot cruder than the refined or nue pieces from the Low Countries, it is actually quite high-quality. Many different techniques are being used for both the goldwork and the silk embroidery. For instance, the curley hair of Baby Jesus is made by overtwisting silk and couching it down. The silk embroidery in the faces is mostly vertical shaded brick stitching for the flesh with finely added detailed stitching for the facial features. These are not 'an official type of stitch'. The embroiderer painted with needle and thread to add the eyes, nose and mouth. The folds in the garments have been padded with string padding. The gold threads have been couched over these. Thick silken stitches accentuate these folds further. The rays of light behind Mary have also been padded heavily. But that's not all! Above, you see a detail of Saint Barbara with her tower. If you look closely, just to the left of her nimbus, you can see the string padding that's underneath the diaper pattern of the background. The double chevron pattern is created by couching over horizontally laid string padding. And we see something else that seems to be characteristic of some German embroideries: a thick textile thread wrapped in a thin metal thread. This metal thread is thinner than that used for the rest of the goldwork embroidery. Two of these 'gold gimp' threads are then twisted together and couched down along the edge of the neck opening of the garment and along the edge of the nimbus. I am wondering how they made this thread. Did they put some kind of glue on the thick textile core before they wrapped it tightly with the thin metal thread? I am also thinking that this metal thread is a membrane gold rather than a passing thread. It must be rather 'soft' to accept such tight and uniform coiling around the textile core. I have the suspicion that a passing thread would be too stiff or would show marked bends. Any thoughts? Literature

Weed, S.E., 2002. The Virgo inter virgines: Art and the devotion to virgin saints in the Low Countries and Germany, 1400--1530. Dissertation University of Pennsylvania.

6 Comments

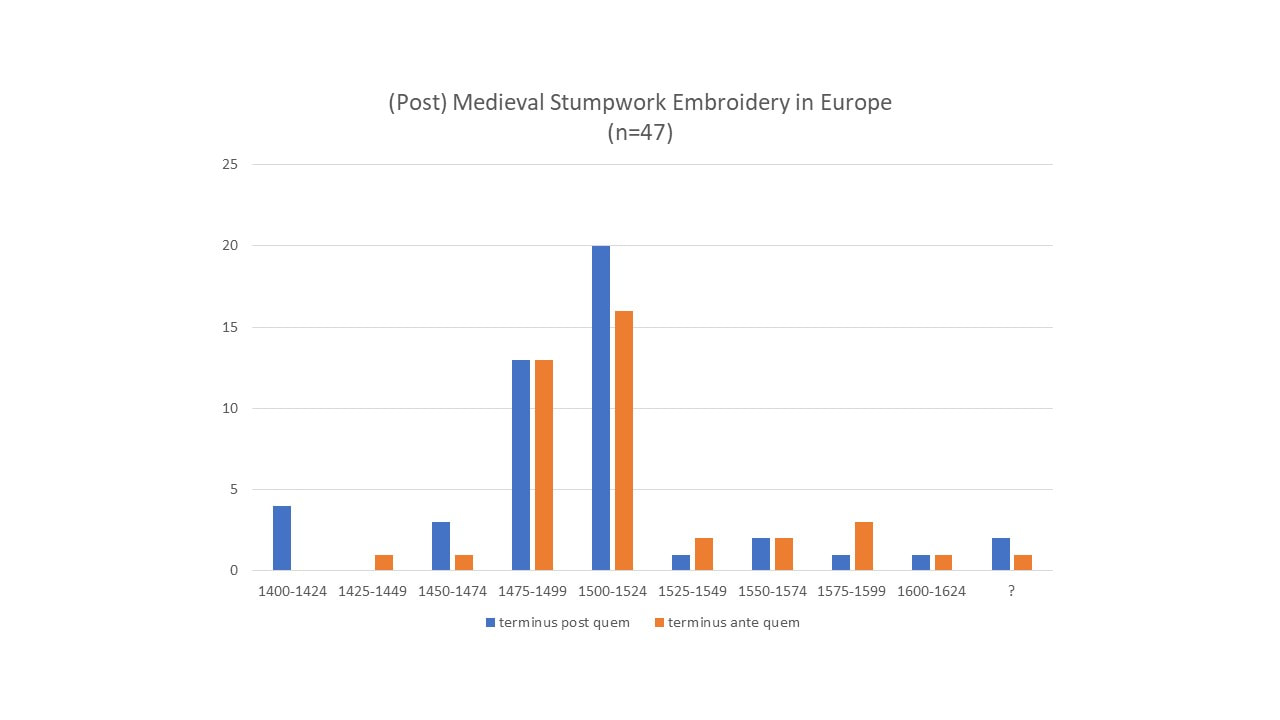

Earlier this year, the Diocesan Museum Freising opened its doors again after extensive remodelling. As it is not too far from where I live, I decided to check it out in case any medieval embroidery was on display. It turned out that they have a stunning chasuble with very high-end embroidery on it. Unfortunately, there were no captions in the museum. I emailed them and wrote an official letter. To no avail. They never answered. Frustrating as this is, it is unfortunately, a reality when it comes to European museums. Museums in the UK or the USA are usually very helpful. Museums in Europe usually do not even bother to answer, let alone host me for a research visit. This undoubtedly is the result of how museums were and are financed in the respective countries. And with the 'distance' between lay people and experts. Despite having a doctorate in archaeology, being a professional embroiderer and having studied medieval goldwork embroidery for a number of years, this does not always make me an expert :). So, let's see what we can find out on our own about this stunning piece of embroidery! The chasuble cross on the back shows an interesting scene at the top: the mystical marriage of Saint Catherine. As far as I am aware, this is the only embroidered version of this particular episode. There are more embroidered scenes of the life of Catherine, but this one seems unique. The scene is flanked by two angles. One playing the harp and the other a lute. Below the central scene, Saint Margaret is depicted with the dragon. The beast playfully bites into her standard. The Saint at the bottom is Dorothea with her basket of flowers. Catherine, Margaret and Dorothea are known as the virgines capitales. As you can see, the orphrey has been cut at the top and at the bottom. Furthermore, we cannot see the front of the chasuble which might also have an orphrey. But the fact that the virgines capitales are usually four saints gives us an idea of what is missing: Saint Barbara with the tower. A further likely candidate is Mary Magdalene. As said, the embroidery is very high-end. The silk-shading is very finely executed. Both in the actual shading and in the regularity of the stitches. There's no or nue, which gives us our first hint of where the orphrey was made. Or nue is typically something of northwestern Europe (the Low Countries and Northern France) and Southern Europe. It was not really used in England or in Central Europe. As the stitching is very high-end and England does not seem to produce outstanding medieval embroideries after the heyday of Opus anglicanum, we can rule out England as the place of origin. This leaves Central Europe as the most likely candidate. The diaper pattern used in the background of all three sections of the orphrey is unusual too. I know of only one other instance where this pattern has been used: on an Italian orphrey with Bartholomew the Apostle in the Indianapolis Museum of Arts. Those orphreys are clearly Italian and date to AD 1500-1550. The orphreys on the chasuble from Freising are clearly not Italian. And the strong red couching stitches also support this (yellow is preferred in Italy). Another important characteristic of the embroidery on this orphrey is the padding. Especially the arches above the central scene and above Saint Margaret are very highly padded. It would not surprise me if a little bit of wood is hiding in the most-padded parts. In contrast, the figures and the rest of the scenes show very little padding. There's a relatively short period in the history of Central European goldwork when voluminous padding techniques (think stumpwork) really take off. Pieces belonging to this form of embroidery date from about AD 1400 until 1600 (some have a really wide date range assigned to them). However, when the dates are plotted for the 47 pieces in my database, we see that they cluster on either side of AD 1500. I, therefore, think that the orphreys on the Freising chasuble probably date between AD 1475 and AD 1525.

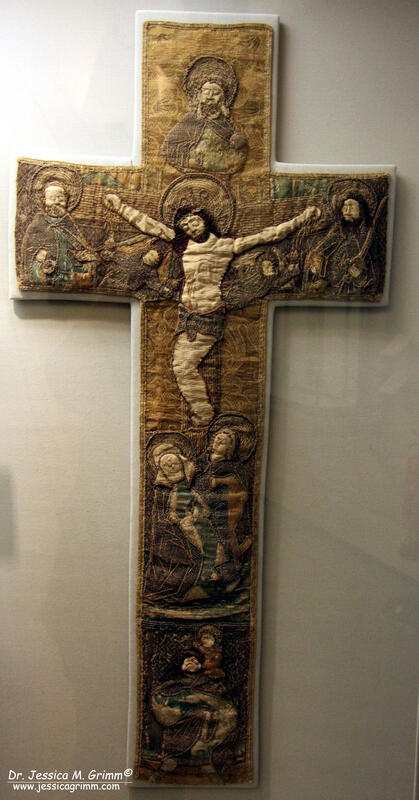

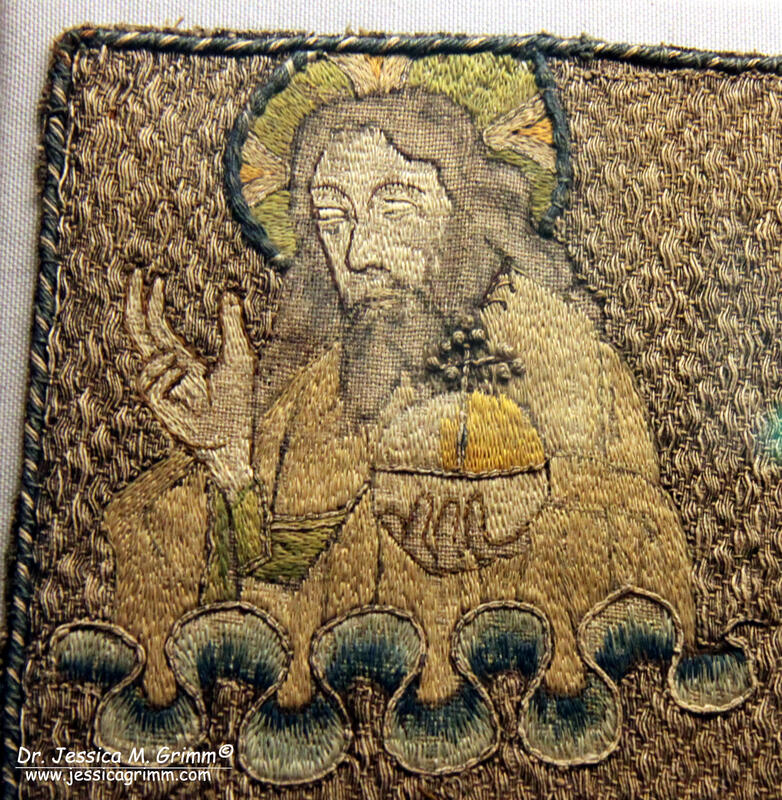

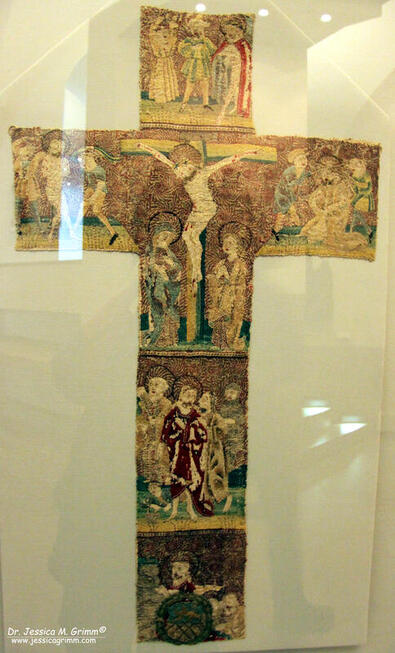

It is thus probably safe to say that the beautiful orphrey on the Freising chasuble was made somewhere in Central Europe around the turn of the 16th century. If you would like to see more pictures of this piece, please consider becoming a Journeyman or Master Patron. As a Journeyman or Master Patron you'll have instant access to a further 12 pictures of this piece. The monthly support of my Patrons enables me to keep this website running! Last week's beautiful Bohemian chasuble cross was a bit large to discuss in a single blog post. And it turned out to be even more interesting. So here is part II. On a personal note: I rarely display the crucifixion scene prominently on my blog. Just like the early Christians I see an execution. However, this particular crucifixion has such beautiful embroidery and such an interesting alteration story to tell that it would be a shame not to show it to you. And there is a mystery padding technique I hope you might be able to identify. But above all, it prominently displays my favourite biblical power woman: Miriam of Magdala. Unlike Yeshua's male companions, Miriam of Magdala did not cowardly flee but endured watching Yeshua's execution. Her grief of losing her best friend is beautifully captured in this Bohemian embroidery. As is often the case in Central Europe, Miriam kneels and embraces the wooden column of the cross. She is all alone. Emphasising the special bond between Yeshua and her. Not an adultress (that's an invention by Pope Gregory I and was revised by Pope Paul VI) but a primary witness of the life and death of Yeshua. The very fine split stitch embroidery on the body of Yeshua has degraded to such an extent that the beautiful underdrawing has become visible. It is more than a simple line drawing and also shows shadows and many anatomical details. There is a red dye (probably madder) under the halo and on the beams of the cross (but avoiding the left arm). Clearly the work of a pro. The figure of Yeshua was worked as a slip and couched over the voided area of the sunny spiral background. You can see a gap between the top of the halo and that background. The halo has been elaborately padded with different shapes of parchment. If you look closely, you can also spot some later repairs. There are newer silk stitches in the crown of thorns, the hair and around the outline of the cross. You can even spot some newer goldthread under the right arm (left side of the picture). Also, the crude couching stitches visible on the right (left side of the body) are not original. And here is another detail. See the vertical line in the middle above the arm? That's a seam. Two different pieces of linen were joined here. The linen on the left is a bit finer than the linen on the right. It looks like a seam on both pieces was turned under and then the two pieces were slip stitched together. This seam was not visible when the embroidery was new. Because, if you look closely along the edge of the beam of the cross you can spot the remnants of a golden coloured fabric (probably silk). The order of work seems to have been to draw the cross on the linen background (pieced together from at least two pieces of linen) with ink and/or charcoal. Red paint was added to the beams of the cross. Then the golden background was stitched. Then the silk was appliqued over the beams of the cross and embroidered over (where the seam is, the silk of the beam lays on top of the spirals to straighten the beam and correct the line drawing). Then the figure was stitched to the background. Again, the red line along the beam and the blood splatters are later additions. The red of these later additions is much brighter than the original red silk used to edge the vertical beam (to the right of the halo). And here is the figure of Miriam of Magdala. For the most part, she is worked as a slip too. However, to get the perspective right, the last part of her right forearm is worked directly on the linen background of the sunny spirals. It even looks like there is a partial sunny spiral below the silken split stitches. It seems the embroiderer changed the design when the slip was attached. The colours are a little off too and the stitching isn't as neat as that of the rest of the arm. What is going on here? Here is another detail of the figure of Miriam of Magdala. As with the cross, there is a piece of green silk attached behind her halo. But something isn't quite right. The figure is appliqued onto the halo. The green silk is backed with a piece of coarse linen dyed a dark brown. It is not the same linen as seen behind the sunny spirals. The halo was thus not directly stitched onto the background linen on which the sunny spirals were stitched. And look at the gold thread. The gold thread in the halo (and that running along the seam of the headdress and the garment) is much shinier and hasn't oxidized in the same way as the gold thread of the sunny spirals. This is an indication that the thread in the halo is of a later date than that of the background. The thick crude white string at the top part of the halo would have been the padding for pearls. This again seems a later addition. And what about the broad padded seam along the edge of the headdress? What is it? How was it made? It seems to be stitched on top of the fine split stitches and could thus be a later addition as well. Do you recognise the technique? If so, please leave a comment below! And then there is her nose! When I first saw this, I was reminded of the parchment padded noses sometimes seen in Opus anglicanum (for instance: V&A 28A-1892). However, could it be that Miriam's nose was instead damaged at some point? The stitches are a little different and the colour of the silk seems a bit off too. The repair might account for the padded effect seen today. So. What the flip is going on? Well, I think that this beautiful Bohemian embroidery was taken apart when the current chasuble (or possibly an older predecessor with the same cut) was constructed. You see, when the original chasuble cross was stitched around AD 1380 the form of the chasuble it would have been appliqued onto was very different. It was much larger. Chasubles before the 13th-century were voluminous bell chasubles. Due to changes in the liturgy (elevation of the host) the priest needed more arm room and the chasuble became increasingly smaller. This eventually lead to the minimalist violin case shape of this 19th-century chasuble. This meant that older embroideries were too large and needed to be adapted. Often, they were simply cut off with little regard for the embroidered scenes.

Not so in this case. It seems that the figures were carefully taken off the sunny spiral background. The crucifixion cross was probably remodelled (cross beams and column shortened) and the silk was added. Miriam was given a new halo. She would have originally sat further down the column of the cross. When she had to be moved up, she either never had a halo or the halo could not be moved because it was part of the background (now possibly beneath her clothes). Due to the now shortened 'canvas' the pelican was moved down and now sits almost on top of Yeshua's halo. The figure of Yeshua is probably not quite in its original place either. A patch of newer gold thread next to his feet (big toe right foot) shows that originally something else was going on here. Maybe all the additional silk embroidery dates from this major remodelling too. All in all, it shows that this beautiful embroidery was valued and got a second lease of life. Literature Stolleis, K., 2001. Messgewänder aus deutschen Kirchenschätzen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Regensburg, Schnell & Steiner. Wenzel, K., 2016. Görlitzer Kasel. In: J. Fajt & M. Hörsch (eds.), Kaiser Karl IV, 1316-2016. Ausstellungskatalog. Nationalgalerie in Prag, p. 505-508. Happy New Year to you all! My 2020 started with a 630 km round-trip to Bamberg. The diocesan museum houses some of the finest medieval goldwork embroideries in Europe. These exquisite pieces are a staggering 1000-years old! I was able to take some good pictures, which I am going to share with you here. Unfortunately, there was virtually no information available in the museum so I can't really tell you much about the pieces. However, I've ordered some literature and will do a further post with those details when the papers arrive. Probably the most famous piece held at the museum is the so-called "Sternenmantel Kaiser Heinrich II des Heiligen" (star mantle of Saint emperor Henry II). It was used as a cope or pluviale and measures 297 cm by 154 cm. The mantle shows Christological depictions, astrological signs and 14 roundels with busts of saints and many Latin inscriptions explaining what is depicted. Unfortunately, the gold embroidery was re-applied to the blue Italian silk damask we see today in 1503. The original design got mixed up and not all writing makes sense. Some scholars argue that in fact two mantles were made into one. The original background fabric was a dark-purple silk samite. Traces can still be seen on the inside of the different design elements. When the pieces were transferred onto the new blue damask, the edges were covered with a thick white strand of silk couched down with a thinner strand of white silk. To have an even better attachment, some of the design lines on the inside were covered with split or chain stitches using red silk. The original gold embroidery uses VERY fine passing thread and white, red, blue and green silk for the couching stitches. It looked to me that the passing thread has been couched as a single thread, rather than in pairs. Traditionally, this mantle is dated to AD 1010-1020 and its place of origin as Regensburg with a ?. The mantle is seen, based on the embroidered inscriptions, as a gift from Melus of Bari (died 1020 in Bamberg) when he sought the support of Emperor Henry II for his revolt against the Byzantine Empire. It is, therefore, more logical that the mantle was made in Southern Italy. The second famous mantle held at the diocesan museum in Bamberg is that of Saint Kunigunde, wife of emperor Henry II. This cope measures 286 cm by 162,5 cm and shows biblical scenes, a.o. related to Christ saviour and to the lives of the patrons of Bamberg Cathedral: St. Peter and St. Paul. Lettering around each roundel explains the stitched scenes. This cope was likely a donation by empress Kunigunde to the cathedral and made around 1020 AD in Southern Germany. The original VERY fine goldwork embroidery was stitched on a background of blue silk twill. There are 56 parallel passing threads per centimetre (!!!) and this means that each passing thread (a strip of gold foil spun around a silk core, see my previous blog on the manufacture of gold threads) had a width of about 0.18 mm. In comparison: my finest passing thread (Stech 50/60 CS) has a width of 0.22 mm. Pretty mindblowing, don't you think?! For the figures, these parallel passing threads lay vertically and are couched down in several different patterns using white, red, light- and dark blue silks. Further details are stitched in stem stitch. The embroideries from this mantle have also been re-applied onto a new fabric in the 16th century. Why have these two pieces survived in such splendid condition? This is due to the fact that both copes or mantles were related to the emperor and his empress. Both were sanctified. Bamberg employed these famous saints for their own marketing purposes since the late Middle Ages. This is likely the reason why the pieces were re-applied and probably altered then. Quasi to strengthen the case of the link between Bamberg and these two saints. Currently, a four-year research project on these vestments runs until 30-09-2020. For the first time, the art historians are employing scientific techniques to determine the origins of the materials used in these exquisite goldwork embroideries. We can thus look forward to a volume of papers being published on the subject in the coming years! Literature Enzensberger, H., 2007. Bamberg und Apulien, in: Das Bistum Bamberg in der Welt des Mittelalters (=Bamberger interdisziplinäre Mittelalterstudien. Vorträge und Vorlesungen 1), C. & K. van Eickels (eds), p. 141–150. Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2014. O Decus Europae Cesar Heinrice? Die Saumumschrift des sogenannten Bamberger Sternenmantels Kaiser Heinrichs II, Archiv für Diplomatik, Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde 60/1, p. 135–164. Schuette, M. & Müller-Christensen, S., 1963. Das Stickereiwerk. Wasmuth. No ISBN. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤!

When I was in Trento, Italy, a couple of weeks ago, I did also visit the Diocesan Museum. It houses an important and impressive collection of ecclesiastical art. The building itself is the old Praetorian Palace where the Prince-Bishops of Trento lived. From one of the rooms you can actually look down into the Cathedral. Quite a spectacular sight! Although the museum houses many exquisite works of art, my main concern where the embroidered vestments. There are a few very fine examples of medieval goldwork embroidery on display. The most important pieces consist of a chasuble cross and five orphreys from a dalmatic (vestment worn by the deacon). The sublime silk and goldwork embroidery was executed between 1390 and 1400 in Bohemia. Now part of the Czech Republic, but then an important and independent kingdom ruled by the House of Luxembourg. Charles IV (1316-1378) became king of Bohemia and also Holy Roman Emperor in 1346. He is the founder of the Charles University in Prague, the first one in Central-Europe. This was Bohemia's Golden Age and it is thus no wonder that there were embroidery artists of this skill working within its borders. The chasuble cross and the orphreys are part of the vestments made for Prince-Bishop Georg von Liechtenstein (reign 1390-1419). He was born in Moravia. Now part of the Czech Republic and bordering Bohemia. Since AD 955 it formed a union with Bohemia. It seems that Georg patronised local Bohemian/Moravian embroidery artists when he moved to Trento in AD 1390. But on the orphreys he had them tell a typical Tridentine story: the vita of Saint Vigilius of Trent. The patron saint and first bishop of Trento. I can see why he used his fellow countrymen to make these works of art: the style is rather distinctive. With friendly round faces and bodies. Once you pay attention, you can spot a Bohemian embroidery before reading the museum caption. Perhaps, similarly today, Czech and especially Czechlowakian postal stamps have a very distinctive style. Also on display was a chasuble made of white linen and embroidered with silks. I've written an ebook on these particular vestments made in the 17th century in Tyrol. This particular piece isn't made with great skill :). But the patterns and the colours of the flowers are identical to the flowers on the chasuble from the Diocesan Museum of Brixen. However, the Museum in Trento dates the piece much later: first half of the 19th century. But also admits that not much is known about its provenance.

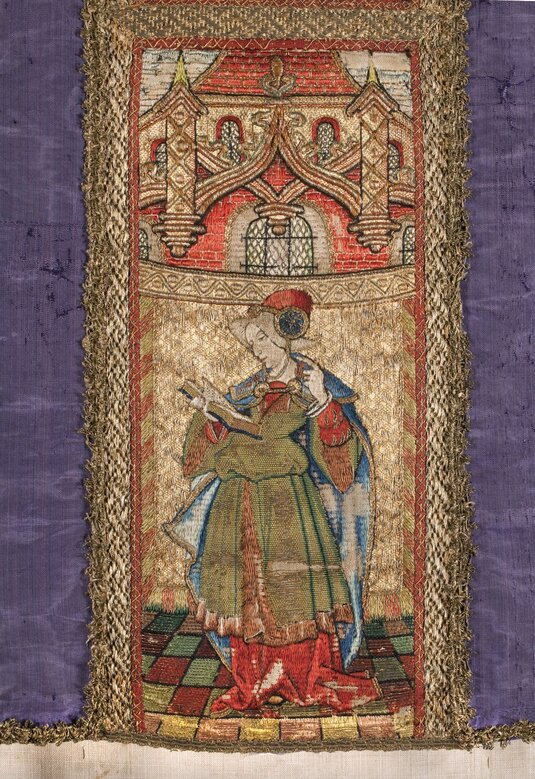

When Trento does not happen to be next door to where you live, the museum published two excellent books (in Italian I am afraid) on its textile collection: Devoti, D., D. Digilio & D. Primerano, 1999. Vesti liturgiche e frammenti tessili nella raccolta del Museo Diocesano Tridentino, no ISBN. Officially out of print, but available second-hand when you ask Google :). Primerano, D. 2011. Una storia a ricamo. La ricomposizione di un raro ciclo boemo di fine Trencento, ISBN 978-88-97372-02-8. Ask Google :). Gold threads and paintings in silk: Velvets and embroidery from the Gothic era and the Renaissance30/9/2019 Last week I was finally able to visit this magnificent embroidery exhibition in the Castello Buonconsiglio in Trento, Italy. It is on until the third of November and I urge you to visit if at all possible as it is as important as the Dutch exhibition in Utrecht in 2015 or the Opus Anglicanum exhibition in London in 2016. And yes there is a wonderful catalogue, but just as the Dutch did, the Italians thought it a brilliant idea to publish the scientific papers on these extraordinary pieces in their own language. At 423 pages, it will take me aeons to translate ... However, it is packed full with stunning pictures of the embroidery. Including many close-ups. Together with the 400+ pictures I took during my three-hour visit, it will be a treasure trove for years to come! You will hopefully understand that I can't publish all the 400+ pictures in this one blog post. Instead, I will concentrate on three (well actually four) extraordinary pieces that were on display. First up is a chasuble made in the middle of the 15th century in Venice. Why did I pick this particular one to show you? If you are used to the orphreys from the Low Countries, these Venetian examples look very different. They show the same main principle: saint in front of some fancy architecture. But the embroidery techniques used are somewhat different. The examples from the Low Countries use much more gold thread for the architectural backgrounds. And their linen background is fully covered with embroidery. Not so in this piece: the background is stitched on green silk. They look airy and light; a typical sign of the art of the Renaissance. The examples from the Low Countries are in comparison much stiffer and heavy. The figures themselves are also embroidered in a different way than the majority of the pieces from the Low Countries. As in the Low Countries, the figures are embroidered onto a linen base. However, the embroidery technique used is a form of shaded laid-work using untwisted coloured silk for the undergarments. Simple couching of pairs of fine passing thread for the cloak and fine silk shading for the faces and hands. The figures in the orphreys from the Low Countries are mainly done in splendid or nue. Unfortunately, the stiffness of the linen base in comparison to the lightness of the green silk makes the piece pucker. Not easy to photograph! Most incredibly, this chasuble is still worn every 3rd of May on the feast of the Apostles Philip and James! Next up is an example of a chasuble which fascinates me hugely. This is serious stumpwork made at the start of the 16th century somewhere in the German-speaking parts of Central Europe. You come across this type regularly in this part of the world (there are in fact two more in the exhibition), but this is an exceptionally stunning piece with highly sculptured figures. The faces are incredible! And look at Jesus's curly hair. A theory put forward by Aleth Lorne (2015, p. 99-102) to explain these highly sculptural pieces is that the embroiderers and the woodcarvers in the German-speaking parts of Central Europe influenced each other in their search for the three-dimensional rendition of the world. Both craftsmen were often part of the same guild and probably used the same designs made by yet another craftsman. These pieces were so well-known that they are recognisably depicted on paintings from the same period, but not necessarily from the same area. People were clearly fascinated by these pieces. Particularly good examples further adorned with thousands of fresh-water pearls can be seen in the treasury of the Basilica of Mariazell in Austria. There is just one thing about this chasuble which I do not understand. See the bottom? Someone brutally cut through Saint Joachim when the taste in chasuble shapes changed from wide to a violin-case. This probably happened in the 17th century (Stolleis 2001, p. 29). I hope the scissors wore out :). And last but not least, I am going to show you two dalmatics (vestments worn by the deacon) made in the Netherlands at the start of the 16th century. These new acquisitions by the museum lead to this exquisite exhibition. They are displayed in the last room together with three other chasubles. And the best thing is: they are not behind glass! You can get up close and personal with them :). The orphreys on these dalmatics are of the typical type seen on vestments from the Low Countries from this era (you now clearly see the difference with the first chasuble I showed you which was made in Venice). Completely covered in embroidery and featuring beautiful or nue on the figures. The pieces are quite similar to the vestments made for David of Burgundy, bishop of Utrecht in the 15th century. They are in fact so similar that I for a moment thought that they were the ones made for David.

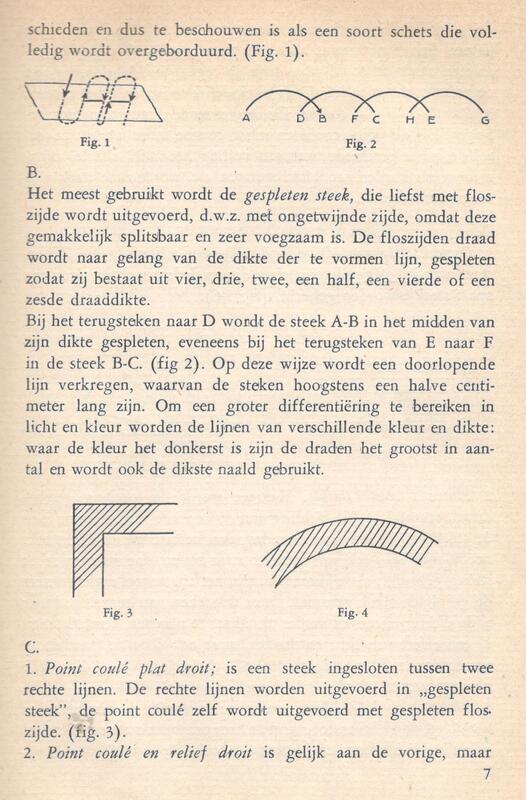

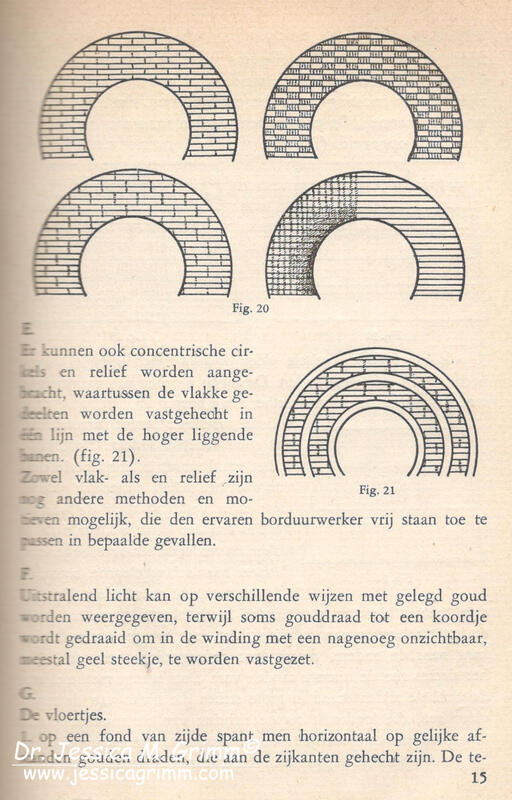

The vestments made for David were probably embroidered by an atelier in Utrecht. These slightly later dalmatics could either be embroidered in Amsterdam or indeed Utrecht. I got the giggles when I saw that the museum Castello Bonconsiglio thinks that Amsterdam and Utrecht are situated in Flanders. Not quite. But close :). Sources: Dal Pra, L., M. Carmignani & P. Peri (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Castello del Buonconsiglio. Lorne, A. (2015): Borduurwerkers en beeldhouwers in de Nederlanden en het Rijnland in de late Middeleeuwen. In: M. Leeflang & K. van Schooten, Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden, Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht, pp. 95-103. Stoleis, K. (2001): Messgewänder aus deutschen Kirchenschätzen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Regensburg. P.S. If you like what you see, please consider making a donation using the PayPal button in the right-side column. Hugely appreciated! This might not come as a surprise to you: I love books on embroidery! Not only the so-called project books or books on a particular technique, but also museum catalogues and research papers. Whilst the first are usually promoted by and within the embroidery community, the later are a little harder to find. Second-hand bookshops are a good place to look for them. Since the topic is such a specific one, the people in the bookshop can often tell you in an instant if they carry some. Recently I rediscovered one such book in my extensive library. It is a Dutch doctoral thesis from 1948 written by Dr. Beatrice Jansen (1914-2008). The title of the thesis defended at the University of Utrecht is: Laat gotisch borduurwerk in Nederland (Late Gothic embroideries from the Netherlands). I bought the book years ago as I liked the technical and design drawings, but I had never actually read it ... Until now. And it actually is a gem! Let's explore together ... The first chapter concerns itself with the embroidery techniques used. Dr. Jansen was probably not an embroiderer, but certainly a true art-historian. Back in the late 1940s, art-historians used French and German sources for their research. Dr. Jansen copied the French names of embroidery techniques from 'La broderie du XIe siecle jusqu' a nos jours' from L. de Farcy printed in Paris, 1892. You can find an online digitised copy of the catalogue and all the black-and-white photographs here. Although these are truly lovely, I would rather have had a digital copy of the chapter with the embroidery techniques explained. It is quite difficult to understand what Dr. Jansen is talking about. The other source used is a German one: 'Künstlerische Entwicklung der Weberei und Stickerei' by M. Dreger written in 1904. This book can also be viewed online. However, this is only the text. They didn't digitize the plates ... Both books are still around and can be purchased from book dealers. However, they sell for hundreds (till thousands!) of euros. So I probably go to the library in Munich :). That said; when Dr. Jansen really dives into the embroidery seen on the Dutch liturgical vestments, she does present a lot of rather lovely technical drawings. And that's the true merit of this book. The next chapter is a lovely one too! Dr. Jansen presents all the historical sources concerning medieval embroiderers or acupictores as they were called. The female form, acupictrix was rare and only used as 'wife-of'. Indeed, professional embroidery was a male occupation and females only seemed to have contributed in the ateliers of their husbands (and maybe fathers). What is also interesting, the embroiderers did not have a guild of their own. They were usually part of the guild of the painters as they were seen as 'painters with thread'. The embroiderers did not only stitch new vestments; they are explicitly required to mend existing ones as well. And, this doesn't really come as a surprise: the job wasn't well paid and did not have the same standing as that of artisans working in the 'high arts' like painters and sculptures. Discrimination against textile art certainly has deep roots! The next two chapters try to divide the gothic vestments into a group made in the Northern Netherlands (roughly present-day Netherlands) and a Southern group (roughly present-day Belgium). These chapters are pure art-historian. Due to the fact that this book is so old, not all pieces talked about are represented by a black-and-white photograph in the catalogue. But lo-and-behold, I own a modern catalogue from the exhibition in the Catharijne Convent in 2015! So I wrote the modern catalogue number and, if applicable, the inventory number into the margins for quicker reference. Even before the publication of Dr. Jansen, art-historians have tried to name the artists who made the design for these vestments. Successful matches could be made with paintings, woodcuts and sculptures of which the names of the artists have survived. It becomes evident that prints circulated in the embroidery ateliers after which the embroidery was executed. Clients would have had very specific ideas about what they wanted on their vestments and in which style. Chapter V tries to further categorize the vestments by looking at the embroidered architecture. When you start looking at these vestments, you soon realize that certain elements of the architecture are very similar between different pieces. This chapter is richly illustrated with line drawings of all the different architectural styles found on the orphreys of the vestments. Chapter VI high-lights that these kind of embroideries were made at least a century earlier than the pieces that have survived in modern-day museum collections. The oldest painting depicting this type of embroidery is the Ghent Altarpiece made by Hubert and Jan van Eyck between 1427 and 1432. This chapter lists nearly 60 other paintings depicting this type of embroidery. The thesis concludes with a sammery in Dutch and English. I also found a rather embarrassing remark in the margin made by a previous owner. It reads 'Hier had ik nu eens graag gehoord, welke mof dit woord invoerde en welke hollander dit germanisme' (I would have loved to hear which mof (= Nazi) introduced this word and which Dutchman came up with this germanism). Remember, this book was published only three years after the end of the Second World War ...

Since this book was published so long ago, you can only find it in libraries (all over the world as it is a doctoral thesis!) or second-hand. Unfortunately, only more modern theses are available online from the University of Utrecht. And since the author died only 11 years ago, it will take another 59 years before the book can be digitised by me and put into the public domain :). I can probably just manage that before turning 100! Last week, I showed you the vestments from the 17th and 18th century on display at the Dommuseum in Fulda. This week we will have a look at the medieval ones. Although the lighting was much better in this part of the exhibition, the glass of the showcases posed a huge problem when photographing the pieces. And to make matters worse, the warden revoked my permission to photograph. Nevertheless, I have a hand-full of nice pictures of very high-end goldwork and silk embroidery to share with you! First up are two pictures of an embroidered cross which would have adorned a chasuble. These embroideries were so precious, that they were mostly re-used on a new vestment when the old one was worn. In this case, the embroidery is a little special: it is raised embroidery. We often associate stumpwork embroidery with 17th-century England. In this case, however, the embroidery was done around 1500. The exact provenance was not stated, but these stumpwork embroideries were all made in the German-speaking parts of Europe. The most exquisite examples can be found in Mariazell, Austria. Here the figures stand about 3 cm proud of the background fabric! In the detail picture above, one can clearly see that the faces of both Peter and Jesus are padded. Jesus's ribcage is defined with a piece of string padding. The whole figure of Jesus seems to be somewhat padded. And the flesh-coloured fabric looks quite stiff and a bit like paper or vellum. And here we have two depictures of God from two different late-medieval chasuble crosses. Unfortunately, no further information was displayed for these two. Or maybe I forgot to take a picture ... I quite like these two. The clouds remind me somewhat of Chinese embroidery on the imperial Dragon Robes. Last up are these two. They are chasuble crosses embroidered around 1480. No provenance is given. These two caught my eye as the embroidery techniques used are quite different from the other vestments on display. No or nue here; the figures are stitched in silk using long-and-short stitch. In this detail shot, you can see what I mean. No or nue for the figures here. Instead, there is meticulous tapestry shading on the clothing (i.e. silk shading strict vertically instead of naturally). And the couching patterns for the goldwork threads in the background are so full of movement and quite different from the strict geometrical patterns seen in the late-medieval vestments from the Low Countries. I had a strange feeling that I had seen this before. And luckily for me, my mind sometimes does a good job :). Instead of needing to go through my thousands of pictures taken at museums, I knew at which museum I had seen this: the Diözesanmuseum Brixen, Italy. This late-15th-century (same date as the one from Fulda!) chasuble cross has a similar couched background. And most of the figures are stitched in tapestry shading rather than or nue (Mary being a notable exemption). So maybe the chasuble cross held at the Dommuseum Fulda has a more southern origin?

Being able to make these connections only works when I am allowed to take pictures. As lighting conditions or the way things are exhibited often do not permit studying the embroidery with the naked eye, my pictures are a great help. The camera is able to pick up details even when lighting is poor. I can zoom while taking a picture and again when looking at my pictures on the computer. Applying filters will tell me even more about the way things were made. It is therefore always very sad when the taking of pictures is not permitted. As long as you do not use flash (or use another source of light such as your phone!), you are not damaging the exhibits. And me taking pictures of the exhibits as is, has other benefits too. I don't need to make an official appointment for which museum staff needs to 'host' me (they have better things to do) and I don't need to handle the exhibits either. Some museums argue that by taking photographs and publishing them in a blog or on social media will mean fewer people will actually visit the museum. Really? I have the sneaking feeling that more people will visit a museum when they know what is on show. Especially museums with a wide range of exhibits of which textiles are only a small portion. The museum's website often does not specifically state that there are gorgeous embroideries on display (they are a somewhat neglected category, especially when in competition with bling made of precious metals) which might interest the curious embroiderer. And I know that several of my readers have visited museums which featured in my blogs. I have been guilty of doing the same. Maybe we should start mentioning these things to staff on duty when visiting a museum after reading a blog or seeing a picture on social media. What do you think? A couple of weeks ago, I visited the Dommuseum in Fulda. I knew from their website that they had at least some embroidered vestments. Little did I know that they had quite a lot of them! And when I asked if I would be allowed to take pictures, the clerk on duty said that he didn't mind me taking pictures. Unfortunately, he was quite a character and rather unpleasant. Half-way through the exhibition, he told me to stop photographing. No reason was given. Lucky for you and me, I had been able to take quite a few pictures before I was told to stop :). Enjoy the bling ... The above short video was shot with my phone. What you see here is one of the rooms where the vestments are shown. There are several of these large displays. They are reserved for the 'younger' vestments dating to the Baroque and Rococo (17th and 18th century). The vestments are shown in a kind of altar setting interspersed with other liturgical objects. Sets of matching liturgical vestments (cope, chasuble and dalmatic) are grouped together. As you can see the lighting is rather sparse. And the fact that most pieces are placed at a distance from the glass wall, makes studying them almost impossible. The written information was mostly limited to the name of the vestment, the date and the person who paid for it or for whom it was made. Not ideal for the curious embroideress! That said: the dim light and the 'scenic' placement of the vestments did give a good idea of how these gold embroidered vestements would have sparkled all those centuries ago. And that is an impression not many of us get to see nowadays. After all, how likely would it be to sit in a church service in the semi-dark (safety hazard!) with enough senior clergymen present (they are thinly spread these days!) that a full set of these antique vestments (museum people in uproar!) can be worn? And this is a picture of the same display made with my Canon digital camera (no flash, just a very steady hand). On the far left, you'll see a yellow cope behind a yellow dalmatic and maniple. They belong to the so-called Harstallscher Goldornat made in 1802 for the last Prince-Bishop of Fulda Adalbert von Harstall (1737-1814). The vestments are made of silk and gold brocade with some goldwork embroidery. Prominently in the middle of the picture are some red vestments. From the left: chasuble, stola, cope, palla, bursa, pink chasuble, pink stola and dalmatic. They belong to the so-called Roter Schleiffrasornat made in 1702 for Prince-Bishop Adalbert von Schleiffras (1650-1714). It is the oldest complete set of vestments in the museum. The vestments are made of silk and heavily decorated with goldwork embroidery. Detail of the cope hood of the Roter Schleiffrasornat. And this exquisite piece of goldwork embroidery can be found on the hood of the cope belonging to the Weisser Buseckscher Ornat made in 1748 for the Prince-Bishop Amand von Buseck (1685-1756). The fact that Amand was very good at drawing and a sponsor of the arts is probably reflected in the high quality of the padded goldwork on his vestments. Amongst all the bling I discovered what looks like a 17th-century casket of some sorts. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't take decent pictures of it. And there was no information on the piece either. But since I know that there are several 'casketeers' reading my blog, I am including it here anyway.

That's quite enough bling for today me thinks! Although it is quite difficult to see the beautiful goldwork embroidery up close due to the way the pieces are presented, the museum is well worth a visit and even a detour when you are in the area. Especially as they have some even greater embroidered treasures dating to the Middle Ages. But that's for another blog post ... Wow, where did the summer go? We had a lovely 26 degrees yesterday and only 6 this morning... We will even see the first night frost this week! Time to re-home my lovely flowering tropical plants from the balcony to the windowsill :). The cooler temperatures are also a perfect excuse to stay indoors and start a new embroidery project. As I really want to be recognised as an artist instead of a crafter, I need to start making original artwork again. For the past months, I have been thinking about a theme for my upcoming solo-exhibition in August 2019. I seem to be rather good at getting brilliant ideas in the middle of the night :). Luckily for me, I am pretty good at getting back to sleep after these nightly strokes of genius. My husband has a far harder time. After all, I have to tell someone, right? I am planning to make a few embroidery pieces in the style of St. Laurence. Using 16th century goldwork embroidery techniques and artistic language. But addressing modern-day issues like immigration, climate change and consumerism. All unmistakably linked, by the way. First up is Pope Francis. Ever since his disarming 'Buona Sera', I have been fascinated by this man. But what probably fascinates me even more, is how we all seem to project our hopes and dreams on this one man. Francis should address climate change, the role of women, homosexuality, world peace etc. And 'pronto', please! The inconvenient truth however is, that one man, even when he is the pope, cannot accomplish this on his own. Are we willing to help him? To show how our projections tend to make Pope Francis larger than life, I've given him a few extra arms. Like many Hindu Gods have. Two arms and hands form what is called the 'Kanzlerraute', the typical 'everything will be all right' posture Angela Merkel often shows. The background will be closely modelled after an orphrey from a chasuble made between AD 1520-1525 in the Northern Netherlands and now held at the Catharijne Convent under inventory number BMH t2911. I am very grateful for this museum to have given me free access to several high-resolution images of this magnificent piece.

That's all for now. I will spend the rest of the afternoon transferring the design onto 40ct natural linen by Zweigart using a normal lead pencil. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed