|

FINALLY: three years and one month after I ordered the above title, it finally arrived a couple of days ago. It is the third (and last) volume on a research project regarding the Imperial Vestments kept in Bamberg. I have written two previous book reviews which you can find here: volume 1 and volume 2. And I have written several blogs (you can scroll through them) before about the Imperial Vestments. These are six embroidered textiles associated with Emperor Henry II and his wife Kunigunde. They date to the first quarter of the 11th century. Although none of the vestments has survived in its original shape, they are among the oldest complete gold embroidered vestments in the world. Hence, they are unique and pretty important as objects of study. This third volume was the volume I looked forward to the most as it contains the "Art technology and material science aspects" (i.e. the materials and the way they were used) of the research. Let's see if my expectations were being met. The book is divided into two main parts. The first part is written by Sibylle Ruß. She is a conservator and restorer of cultural property. She started her education at an embroidery workshop and finished with a Gesellenprüfung (Journeyman examination) before being trained at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum as a conservator and restorer. Sybille describes each vestment in great detail. Especially the different conserving and restoring measures which took place over the centuries. The original embroidery does not get nearly as much attention. This is a missed opportunity. Some things I miss: how where the gold threads being turned? Are the gold threads plunged or just secured on the front with a few extra couching stitches? What are the stitch lengths of the stem stitches? A huge amount of raw data has been collected for this research. There are tantalising glimpses of this data in the form of drawings of the individual design elements with their gold thread directions and couching patterns. I would have loved a CD with this additional information accompanying the book. I am also missing digital reconstructions of the original embroideries. This has been done for some other medieval goldwork embroideries (most notably the Hungarian Coronation Mantle, which is related to these Imperial Vestments). Some of the embroidery is in such bad shape that a digital reconstruction would have really helped to point out how splendid they once were. The second part of the book is written by Ursula Drewello. She works at the Laboratory Drewello and Weißmann and was responsible for the material science part of the research project. The dyestuff analysis was done by Ina Vanden Berghe of KIK-IRPA the Royal Institute of Cultural Heritage in Belgium. Reading about the exact composition of the gold threads, the angle of wrapping the gold foil around the silken core, the dye used for the silken core, etc., was really nice. But I am missing something here too: how do these parameters compare to the modern gold threads available from M.Maurer in Vienna and Golden Threads and Benton & Johnson in the UK? These three are the main gold thread suppliers in Europe. In a way, they are the descendants of the medieval thread makers. In the second part of the book, there is a whole chapter on design transfer. This is particularly important to us embroiderers. And whilst the chapter is not bad, one conclusion just left me speechless. On three of the vestments (Blue Kunigunde Mantle, Star Mantle and Reitermantle) remnants of the design drawing were analysed. As these remnants did not contain charcoal particles the use of the prick-and-pounce method was excluded. Huh?! Are you kidding me? Really?! All three vestments were made of dark-blue samite. The goldwork embroidery was executed directly on this dark silken fabric. Would any of you use black charcoal for the prick-and-pounce method? I surely hope not. You would use a white powder. And guess what? The remnants of the design drawing of two of the three vestments did contain white substances. The other one used a yellow one. And these substances were (also) used to make a kind of a paint. When you paint over the dots with a similar coloured paint-like substance these two likely mix. When you only have remnants of the design drawing, how can you be so sure that they are not the result of two different steps? Instead, the author proposes that the design was being transferred using templates/stencils. However, they have a tendency to smudge and move when used on textiles with a paint-like substance. Now, let me be VERY clear. I am not saying that the prick-and-pounce method was used for the pattern design transfer on the Imperial Vestments. I cannot prove that. Neither does the absence of charcoal particles prove that the method was not used. As has been the case before with this project, the inclusion of a professional goldwork embroiderer would have helped. I've written about early glitches before: here. Throughout the book, the authors emphasize the high quality and professionalism of the medieval embroideries. These embroideries and their medieval makers would have deserved a professional goldwork embroiderer on the team! And no, that does not need to be me. I am not the only one :).

7 Comments

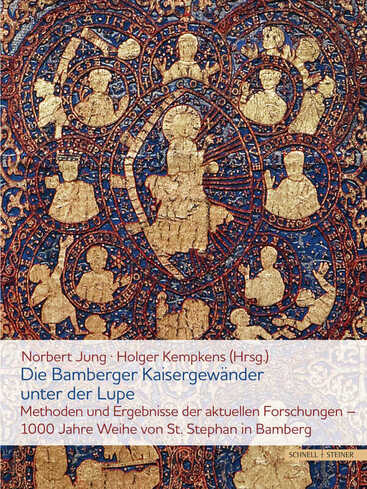

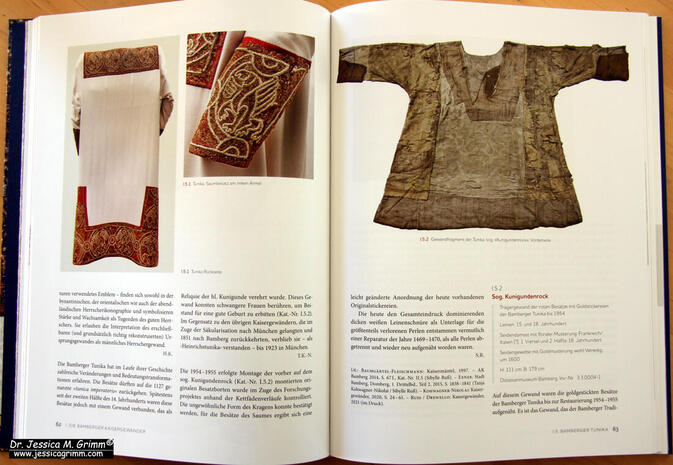

On Friday I got an email from DHL saying that they would finally deliver the next volume in the monograph series on the Imperial Vestments the next day. And they did! Probably due to the worldwide paper crisis, this book has been on pre-order for more than a year. The third, and last volume, is still on pre-order and is said to be released before the end of the year. Since there are three books on the topic, all written in German, it can be a little difficult to determine which ones to order. Read on for my review of the second volume: Die Bamberger Kaisergewänder unter der Lupe - Methoden und Ergebnisse der aktuelle Forschungen (The Imperial Vestments under scrutiny - methods and results of the current research project). When I pre-ordered all three volumes in the series, I wasn't quite sure what to expect from each of them. Reading through the introduction of this second volume, I now understand that this volume was intended as the catalogue for the recent exhibition in the Diocesan Museum Bamberg. This means that the first part of the book (p. 14-97) is the catalogue entries for the exhibits. In essence, this is a summary of the first volume: Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung which I reviewed a while back. Whilst this part contains some new pictures not seen in the first volume, these mainly depict written sources. A tiny part of the book, pages 101-115, describes the art-technological and material science research conducted on the Imperial Vestments. I assume this is a summary of the third and last volume that hopefully gets published before the end of the year. Personally, this is the volume I am looking forward to the most as it promises to hold a lot of technical information important to us as embroiderers. The "summary" on pages 101-115 does whet my appetite but is not meaty enough to satisfy my appetite. The second half of the book (p. 119-209) contains papers on the papal visit in AD 1020 and the consecration of the St Stephan Church in Bamberg. Should you buy this book? Only if you like to have a complete set on your shelves. Whilst the first volume contains a lot of information and beautiful detailed pictures of the Imperial Vestments that are useful to us as embroiderers, this second volume is clearly only intended as a summary for the general public. If I had known what was the content of each volume exactely before buying, I would probably not have bought this second volume. This second volume can be ordered from the publisher Schnell & Steiner.

Jung, N. & H. Kempkens (eds), 2021. Die Bamberger Kaisergewänder unter der Lupe. Methoden und Ergebnisse der aktuellen Forschungen, Schnell & Steiner: Regensburg. A couple of weeks ago, I was alerted to a television appearance of the Imperial Vestments by a blog reader from Germany. In it, one of the researchers is recreating a piece of goldwork embroidery and exclaims that she cannot reach the same quality as the medieval embroiderers once could. The German blog reader wondered in her email what the outcome would have been had a professional embroiderer worked the same sample? As I don't have a television, I hadn't seen the show. However, you can watch it online here, the item starts at 19:48 (you probably need a VPN and set the server to Germany when you are located outside of Germany). It is well worth it, as it has close-ups of the goldwork embroidery on the Imperial Vestments which detail you cannot see when visiting the real pieces. My thought after watching the video? Houston we have a problem! The lady demonstrating the goldwork embroidery started her educational career as an embroidery apprentice. She concluded her learning after two years with a journeyman examination and switched to becoming a textile conservator. This is a transcript of what is being said during the stitching: "Sybille Ruß faces the medieval competition. In a self-test, she wants to find out how tightly she can pack the threads. The result: the embroidery performance back then was downright incredible. So I made a test with the thinnest gold thread and came to 28-30 threads per cm and our top density on the blue Cunigunde mantle is 70 threads. So that goes from 35 to 70 so I wouldn't even have made second place." At the same time, we see her stitch on a pretty slack slate frame. In several close-ups we see her stitch her couching stitches in the wrong direction, i.e. not going down with the needle slightly under the previous row of goldthread. This results in pulling the rows of goldthread apart instead of packing them tightly. It is also evident that the sample we see her work on does have far less than those 28-30 threads per cm. As I really wasn't sure if she knew her experiment did not work because of these basic mistakes I wrote her an email. I promptly received a reply in which she explained that it wasn't a real experiment and that the filming had led to her working the way she did. She was well aware that you need a taut frame and that you couch goldthread in the opposite direction. After all, she had been stitching all day for two years during her professional education. And I am the Easter bunny! To me, this video fragment is the umpteenth proof that embroidery is not being taken seriously. Too often, being a female with nimble fingers is enough qualification to speak about embroidery with authority. During my studies as an archaeologist, I did several courses on archaeological conservation and even did an internship at the County Conservation Centre in Salisbury, UK. However, I decided to pursue a career in archaeozoology, not in archaeological conservation. Would I go onto national television and proudly lecture on archaeological conservation? No way.

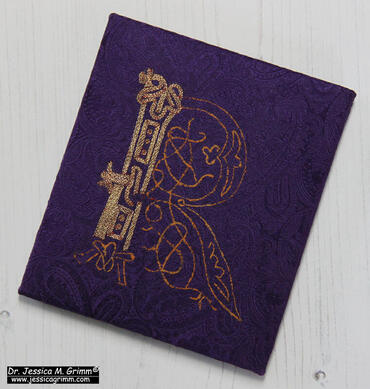

Whilst the research project on the Imperial Vestments shows that they are being taken seriously at a scholarly level, the video (and the makeup of the research team) shows that the practical side perhaps does not get the attention it deserves. Why is there no professional goldwork embroiderer on the team? Embroidery and professionalism do not seem to go together. And the uncomfortable truth is that embroiderers themselves are partly to blame for it. When I was still demonstrating embroidery I got so many non-mindful comments of female stitchers passing by that I decided to stop. The core of most remarks? I wasn't something special. They could do that too. That's not exactly lifting each other up. Men, on the contrary, were often in awe of my skill and professionalism. And some even dared to correct their female companions ... And then there are those embroiderers that proudly exclaim that they are self-taught. In most instances, this seems to mean that they did not go to the Royal School of Needlework :). Learning through books, workshops, blogs, YouTube, etc., for some still seems to mean that they are self-taught. No. You learned self-paced. In all these years, I have never come across someone who was truly self-taught. Not only is it not very nice for the teachers behind the books, blogs and videos that they are not being acknowledged, learning embroidery is also being devalued. Apparently, anyone can figure it out with no help at all! Not good. Please be mindful when you describe your learning journey. Whilst we all figure things out on our own, none of us is truly self-taught. And we teachers know exactly what kind of student you are when you introduce yourself as self-taught. Self-taughts are not the humblest of people and paradox need a lot of attention in class. Next week, I will show you what happened when I tried to pack as many threads next to each other. Was I able to pack more than 30 threads per centimetre? See you next week! As Germany stumbles out of the lockdown we have been in since December, I and my husband took the opportunity to visit the exhibition of the "Kaisergewänder" in the Diocesan Museum Bamberg. Although I visited this museum before, this time the latest research results on the goldwork embroidery were on display. Luckily, my husband was so kind to come on a 660 km round trip with me (promising him cake always works!). If you would like to visit this exhibition yourself, you will have to do so before the end of the month or before the rate of infections rises above the threshold again. You will need to make an appointment through the museum website and fill out a form. So, what new things did we see? First of all, I was really impressed with the amount of information now available for each vestment on display. The original captions were VERY short and that was a major disappointment on my first visit. Secondly, there was a whole room devoted to the "raw data" of the research project. This will probably all become available in the three monographs I have on pre-order. Looking at the tracings and other study results, many of my own assumptions were confirmed. And I learned so much more about these goldwork embroideries that you just cannot see with the naked eye or learn from the pictures I took and enlarged on my computer. A rather interesting piece on display was a copy of the Regensburger rationale. This is a special vestment awarded by the pope to some bishops and was modelled on the ephod of the Jewish high-priest. It is hardly being worn today. The original was stitched in AD 1314-1325, probably in Regensburg. The copy was made for Bishop Franz Wilhelm von Wartenberg (AD 1649-1661) and is now held at the Bayrische Nationalmuseum in Munich (T 178). The copy was likely made to be used by the bishop to spare the original. As you can see, the stitching on the original rationale is made with much finer goldthreads than that on the copy. And now the stalking :). As always, I take many pictures, when allowed. At some point, two women sneaked up to me as they were curious to know who this lady-with-a-Canon-stuck-to-her-face is. It turned out that I knew one of them, Dr Ludmila Kvapilová, scientific associate of the museum (recognising people with a facemask is an art I have not yet mastered). The other lady turned out to be the new head of the museum: Carola Schmidt. Carola trained as a technical weaver before studying art history. The three of us had a lovely conversation and at some point, I mentioned that I had stitched a small sample based on the lettering seen on the Sternenmantel for the conference "Über Stoff und Stein" (you can find my blog on this reconstruction here). They asked if they could display the sample as part of the exhibition. Sure! So, today I mounted the sample and send it to them. This way they can also use it as a teaching aid. I am looking forward to staying in touch with them and to sharing my expertise.

If you would like to learn to professionally mount your finished embroidery, you can find downloadable instructions in either English or German in my webshop. Happy New Year to you all! My 2020 started with a 630 km round-trip to Bamberg. The diocesan museum houses some of the finest medieval goldwork embroideries in Europe. These exquisite pieces are a staggering 1000-years old! I was able to take some good pictures, which I am going to share with you here. Unfortunately, there was virtually no information available in the museum so I can't really tell you much about the pieces. However, I've ordered some literature and will do a further post with those details when the papers arrive. Probably the most famous piece held at the museum is the so-called "Sternenmantel Kaiser Heinrich II des Heiligen" (star mantle of Saint emperor Henry II). It was used as a cope or pluviale and measures 297 cm by 154 cm. The mantle shows Christological depictions, astrological signs and 14 roundels with busts of saints and many Latin inscriptions explaining what is depicted. Unfortunately, the gold embroidery was re-applied to the blue Italian silk damask we see today in 1503. The original design got mixed up and not all writing makes sense. Some scholars argue that in fact two mantles were made into one. The original background fabric was a dark-purple silk samite. Traces can still be seen on the inside of the different design elements. When the pieces were transferred onto the new blue damask, the edges were covered with a thick white strand of silk couched down with a thinner strand of white silk. To have an even better attachment, some of the design lines on the inside were covered with split or chain stitches using red silk. The original gold embroidery uses VERY fine passing thread and white, red, blue and green silk for the couching stitches. It looked to me that the passing thread has been couched as a single thread, rather than in pairs. Traditionally, this mantle is dated to AD 1010-1020 and its place of origin as Regensburg with a ?. The mantle is seen, based on the embroidered inscriptions, as a gift from Melus of Bari (died 1020 in Bamberg) when he sought the support of Emperor Henry II for his revolt against the Byzantine Empire. It is, therefore, more logical that the mantle was made in Southern Italy. The second famous mantle held at the diocesan museum in Bamberg is that of Saint Kunigunde, wife of emperor Henry II. This cope measures 286 cm by 162,5 cm and shows biblical scenes, a.o. related to Christ saviour and to the lives of the patrons of Bamberg Cathedral: St. Peter and St. Paul. Lettering around each roundel explains the stitched scenes. This cope was likely a donation by empress Kunigunde to the cathedral and made around 1020 AD in Southern Germany. The original VERY fine goldwork embroidery was stitched on a background of blue silk twill. There are 56 parallel passing threads per centimetre (!!!) and this means that each passing thread (a strip of gold foil spun around a silk core, see my previous blog on the manufacture of gold threads) had a width of about 0.18 mm. In comparison: my finest passing thread (Stech 50/60 CS) has a width of 0.22 mm. Pretty mindblowing, don't you think?! For the figures, these parallel passing threads lay vertically and are couched down in several different patterns using white, red, light- and dark blue silks. Further details are stitched in stem stitch. The embroideries from this mantle have also been re-applied onto a new fabric in the 16th century. Why have these two pieces survived in such splendid condition? This is due to the fact that both copes or mantles were related to the emperor and his empress. Both were sanctified. Bamberg employed these famous saints for their own marketing purposes since the late Middle Ages. This is likely the reason why the pieces were re-applied and probably altered then. Quasi to strengthen the case of the link between Bamberg and these two saints. Currently, a four-year research project on these vestments runs until 30-09-2020. For the first time, the art historians are employing scientific techniques to determine the origins of the materials used in these exquisite goldwork embroideries. We can thus look forward to a volume of papers being published on the subject in the coming years! Literature Enzensberger, H., 2007. Bamberg und Apulien, in: Das Bistum Bamberg in der Welt des Mittelalters (=Bamberger interdisziplinäre Mittelalterstudien. Vorträge und Vorlesungen 1), C. & K. van Eickels (eds), p. 141–150. Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2014. O Decus Europae Cesar Heinrice? Die Saumumschrift des sogenannten Bamberger Sternenmantels Kaiser Heinrichs II, Archiv für Diplomatik, Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde 60/1, p. 135–164. Schuette, M. & Müller-Christensen, S., 1963. Das Stickereiwerk. Wasmuth. No ISBN. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤!

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed