|

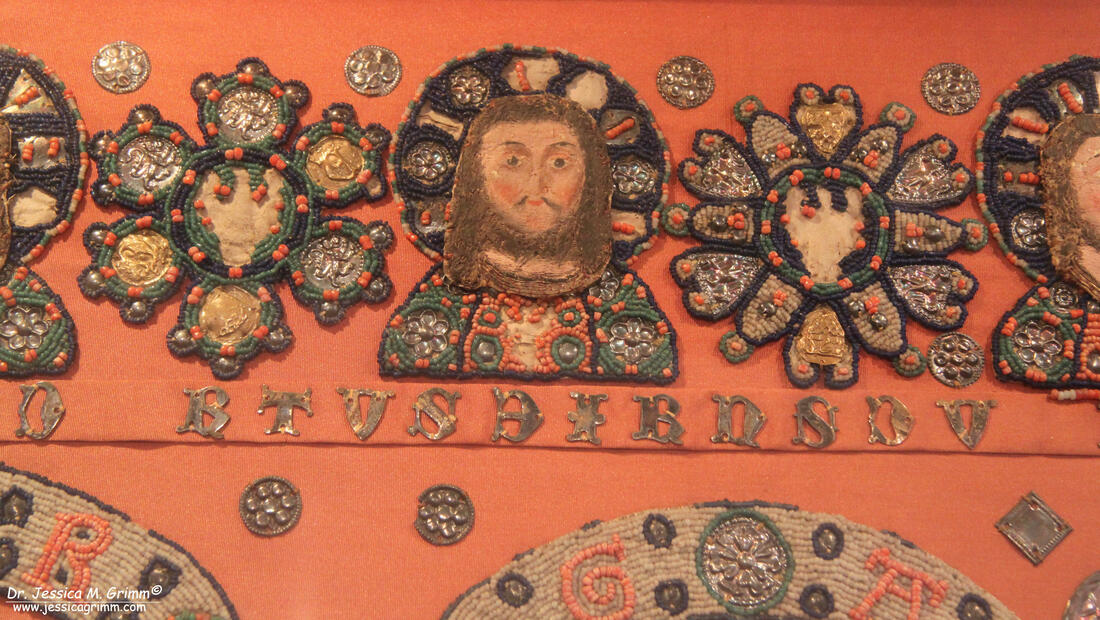

I and my husband had a most lovely trip to Cheb (German: Eger) in the Czech Republic. The local museum houses a spectacular medieval bead embroidery: the Egerer Antependium. Although the museum is closed to the general public due to renovations, Alena Koudelkova kindly agreed to show us around. Check my previous blog post if you want to read the story on how I discovered this gem of a medieval embroidery. The Egerer Antependium measures 2,18 m by 90 cm and was probably made by the Poor Clares of Cheb in the early 14th century (it is a staggering 700 years old!). There are two identical rows with ten saints. Each saint is framed by two columns topped by an arcade. For easy identification, the name of the saint is stitched into the column and the arcade. The bottom row shows (from left): John the Evangelist, James son of Zebedee, James son of Alphaeus, Margaret the Virgin, Mary of Intercession, Jesus (who blesses Mary to his left), Agnes of Rome, Saint Cecilia, Cunigunde of Luxembourg and Saint Ursula. The row above shows: the Archangel Gabriel visiting the Virgin Mary, Agatha of Sicily, Mary with the six-year-old Jesus, Clare of Assisi, Mary Queen of Heaven with baby Jesus, Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Lucy, Saint Barbara and Saint Bibiana. The columns-arcade-frames measure 35 cms in height. The figures themselves are about 28 cms in height. The iconography of this piece supports the thesis that the Poor Clares of Cheb were the embroiderers of this Antependium. For starters: it is very female heavy :). The Virgin Mary is represented four times. She is accompanied by other holy virgins (Margaret, Barbara & Catherine as well as Agnes, Lucy & Cecilia). Clare of Assisi is the founder of the Poor Clares and therefore prominently displayed in the middle of the Antependium. Agatha and Ursula often accompany Clare of Assisi. Cunigunde of Luxembourg is especially venerated in the diocese of Bamberg to which Eger belonged. Bibiana possibly refers to a local veneration or to the sponsor of this piece. Furthermore, in the lower left corner, we see John the Evangelist celebrating mass with the two Jameses as supporting diacons. Especially John the Evangelist was widely venerated by nuns in the High Middle Ages. There is a third row sitting above the previous two rows. This smaller row, a mere 16 cms in height, comprises of the busts of Mary and Jesus flanked by the twelve Apostles. It is quite possible that this row is of a later date. The busts were probably originally silk and goldwork embroideries on linen. The embroidered parts were then covered with paint (I've seen another medieval example in Vilnius, Lithuania). The busts were then cut out and placed on top of the beaded halos. Each bust is alternated with beaded floral motives. A possible later date is supported by the fact that the beads in this row a slightly darker and the metal decorations of a different type. As there are no contemporary written sources, the dating of the piece is mainly based on stylistic grounds. Several of the iconographic scenes are first seen during the mid- to late 13th century. But also the style of the figures themselves discloses the period this piece was likely made. Some of the figures are somewhat stiff and depicted frontally (the Jameses and Clare) whereas most others are depicted more life-like with garments full of movement as was the norm in the later Gothic period. The piece as a whole breathes the strict order of the older Romanesque style. Probably originally made for the chapel of the Poor Clares of Cheb, situated in the Franciscan Church of the Ascension, the Antependium did not stay there. When the Poor Clares got their own church in 1465, they probably gifted the Antependium to the St. Jodok church in Cheb where it stayed until it was transferred to the newly opened museum of Cheb in 1874. Major restorations have transformed the Antependium somewhat. The last one took place in 1928 by Sr. Virginia Erhart of the Congregation of the Holy Cross in Cheb. She worked under close supervision of the County Conservator. It took her over a year to take the beaded applications off the red silk backing from the Baroque period. All beads were cleaned and re-strung when necessary. Then the beaded applications were re-applied to a red silk backing re-enforced by linen. During an earlier restoration, the writing between the first and the second row had already been muddled up and so doesn't make sense anymore. The beaded applications consist of strung beads couched onto vellum. This is clearly seen in those places where the beads are now missing. Sometimes even glimpses of the blue design lines can be seen. The order of work likely has been that firstly those contours were couched. Then the metal decorations were applied before the whole design element was filled with more couched beads. The colour palette is quite restricted with blue, green and white beads being the main colours. Black beads are used sparingly as are the red coral beads and the real gold beads. The size of the beads is remarkably uniform and mainly seems to correspond to a modern bead-size 11. The beads of the face of the Virgin Mary with baby Jesus are real freshwater pearls. These kinds of bead embroideries are very rare. This is due to the fact that their raw material was precious and could easily be recycled. Their origin lies in the pearl embroideries from Byzantium which were made since the 6th century. The idea came to Central Europe in the 9th century through Charlemagne with his contacts to the court of Byzantium. Glass beads were produced in Venice since 1200 AD and they started to supersede the real pearls from the 13th century onwards. These beads had to be imported from Venice well into the 14th century when local production took over (especially in Bohemia, now the Czech Republic). In turn, bead embroidery was superseded by silk embroidery in the 15th century. On the one hand, while beaded embroideries where quite heavy and impractical (in effect, the Egerer Antependium consists of many small embroideries forming a larger piece) and on the other hand while the Renaissance demanded ever more realistic and life-like depictions which couldn't easily be achieved with beads. Sources:

Siegl, K. (1929): Das Egerer Antependium, Unser Egerland, pp. 80-81. Tietz- Strödel, M. (1992): Das Egerer Antependium. In: L. Schreiner (ed.), Kunst in Eger, pp. 248-258. P.S.: This research was partly sponsored by a most generous PayPal-donation of one of my dear readers. If you like what you read on this blog and you can spare some small change, please consider making a donation via the PayPal button at the top of this page!

6 Comments

A couple of weeks ago I was contacted by Mary Gobet, President of the Portland Bead Society, about the beaded antependium (altar cloth) in the Regensburger Domschatz. We had both visited the Regensburger Domschatz a couple of years ago and were intrigued by the piece. However, as it is located behind glass at the top of a flight of stairs, it was impossible to shoot good pictures. And the information only read: Antependium, Regensburg, um 1890, design Vicar Dengler, embroidery with strung pearls, vellum, catalogue number 114. Alles klar? Nope, not really. Together we started to look for literature on the piece and we also contacted the museum for more information. And then it became really interesting! As far as we now understand it, the piece consists of strung pearls couched down on vellum for support. The vellum pieces are then cut out and sewn onto the background fabric. In this case, gold brocade backed by a double layer of linen. The detail and shading of the beads are absolutely exquisite! The piece was originally made in several monasteries of the diocese of Regensburg for the private chapel of the Bishop of Regensburg. It shows Christ Pantocrator flanked by the four evangelists. The two smaller pieces which would have covered the sides of the altar are also held at the museum but are not on display. Mary and I did not know of any other beaded Antependiums. But when we researched the history of this piece, it became clear there are more! Vicar Georg Dengler was the editor of the Magazin Kirchenschmuck (you can browse the magazine by clicking the link; beautiful drawings!) which was printed by Josef Habbel in Regensburg between 1888 and 1895. In the article on the Regensburg Antependium, Dengler states that the antependium was stitched in several monasteries in the diocese of Regensburg. A certain Prof. Klein from Vienna (who had already died before the magazine was printed between 1888 and 1895) had made cardboard templates for the figures. These templates (made of cardboard and in use for embroidery transfers since the Middle Ages) were partly copied by Dengler for his design.

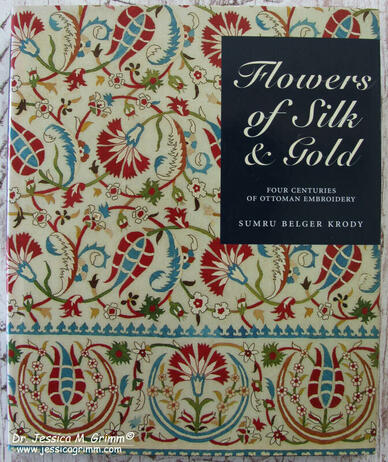

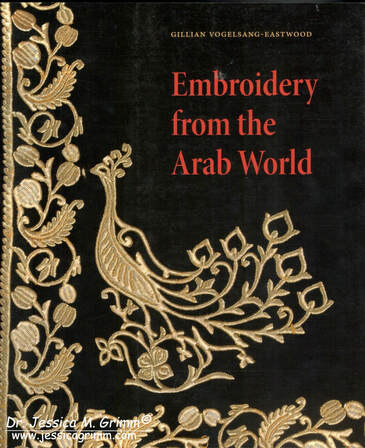

But Dengler got his initial idea from somewhere else. And that somewhere else is modern-day Cheb in the Czech Republic. In Dengler's time better known by its German name of Eger. The museum there houses a medieval beaded Antependium. So I contacted the museum in Cheb and asked if the Antependium is on display. Initially, they told me that the Antependium is on display, but the museum is currently closed for renovations. Bummer! But then I got a second email asking if I would be able to get to Cheb within two to three weeks as renovations on the room with the Antependium had not yet started. Yeah! I am going on a field trip next week :). And I will tell you all about it in my next blog post! Remember the two small black clutches with goldwork embroidery? One of my readers, Monica, suggested contacting the V&A in London to see if they knew some answers to my questions. I immediately wrote them an email. However, the autoreply I got stated that they generally don't do email consultations, but that I would be most welcome to bring my bags to a consultation day in London. Great was my surprise when I did receive an email back a couple of days ago! And this is what their Assistant Curator Jess had to say about my bags: "Many thanks for getting in touch and sharing the images of your bags. These appear to be what have become known as Zardozi bags, based on the Indian Zardozi embroidery technique, and were very popular in the mid-century. They also underwent a bit of a revival in 1980s, with many black velvet bags with vivid gold embroidery upon them in various designs, but usually in a standard size and rectangular shape. The quality and design of your bags suggest these are earlier examples, perhaps even the 1920-30's when exoticism in fashion was rife. I'd suggest these have been made for the tourist/export market, probably hand-worked but by a professional working on quite a mass scale." How cool is that? And Jess's answers explain a few things about the previous answers I got too. For starters, there is the confusion about the dating: 1920-30s, 1950s or 1980s. And as they were mass-produced in India it is small wonder that they are relatively unknown in the Netherlands. But since they were mass-produced, it is quite clear that your average flea market dealer is not going to tell you so even if they know :). Now that I had a name for this type of embroidery, I could search my books and the internet for more. By just typing 'Zardozi bags' into Google, I came across an image of something else my mum had acquired at a flea market: Yup, a glasses case made with Zardozi embroidery. So what is Zardozi? Looks like ordinary goldwork to me, you might think. Right! Zar means gold and dozi means work in the Persian language. The term Zardozi is used for traditional goldwork embroidery from Turkey, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Central Asia and Azerbaijan. A browse through my needlework books resulted in a beautiful picture of Turkish goldwork in Mary Gostelow's "Embroidery: traditional designs, techniques and patterns from all over the world" published in 1977. As is usually the case with these overview books, there is not much additional information in the text. But lo and behold, my library contained two books with large sections on goldwork embroidery from the Ottoman Empire and the Arab World. The book 'Flowers of Silk & Gold: four centuries of Ottoman Embroidery' by Sumru Belger Krody describes the collection of the Textile Museum in Washington D.C. It is a beautiful book with in-depth chapters about the history of the Ottoman Empire, embroidery techniques and embroiderers and the designs and types of embroidered goods as well as a great catalogue of the collection. The book was published in 2000 and the pictures are really good; I highly recommend it if you are interested in Ottoman textiles! What does the book say on zardozi? It describes zerdüz (Turkish form of the Persian word) as an Ottoman embroidery using gold or silver wire or a braid and couching it down with a similar coloured thread. It is apparently similar to Ottoman dival embroidery. So what is dival embroidery? From the description, in the book, it becomes clear that this is gimped couching over cardboard padding. The design could be further enhanced with purls, sequins and pearls. I get the feeling that dival is seen as native to Turkey and zerdüz as foreign. The Ottoman Empire encompassed large stretches of Europe and Asia, so that is understandable. The last book with zardozi embroidery has been written by Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood of the Textile Research Centre in Leiden. It is called 'Embroidery from the Arab World' and was published in 2010. This is an excellent book detailing the history of embroidery in this part of the world from the earliest examples in Egyptian Pharaonic tombs (early 14th century BC) to the modern era. With lots of background information on the history of the regions and social contexts of the embroidery and embroidered items. And the pictures are spectacular and come in great numbers. Another must-have for those of you interested in embroidery from this part of the world!

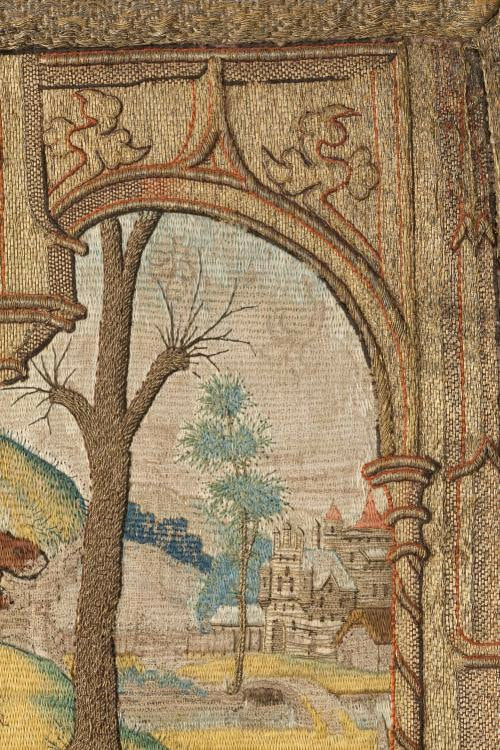

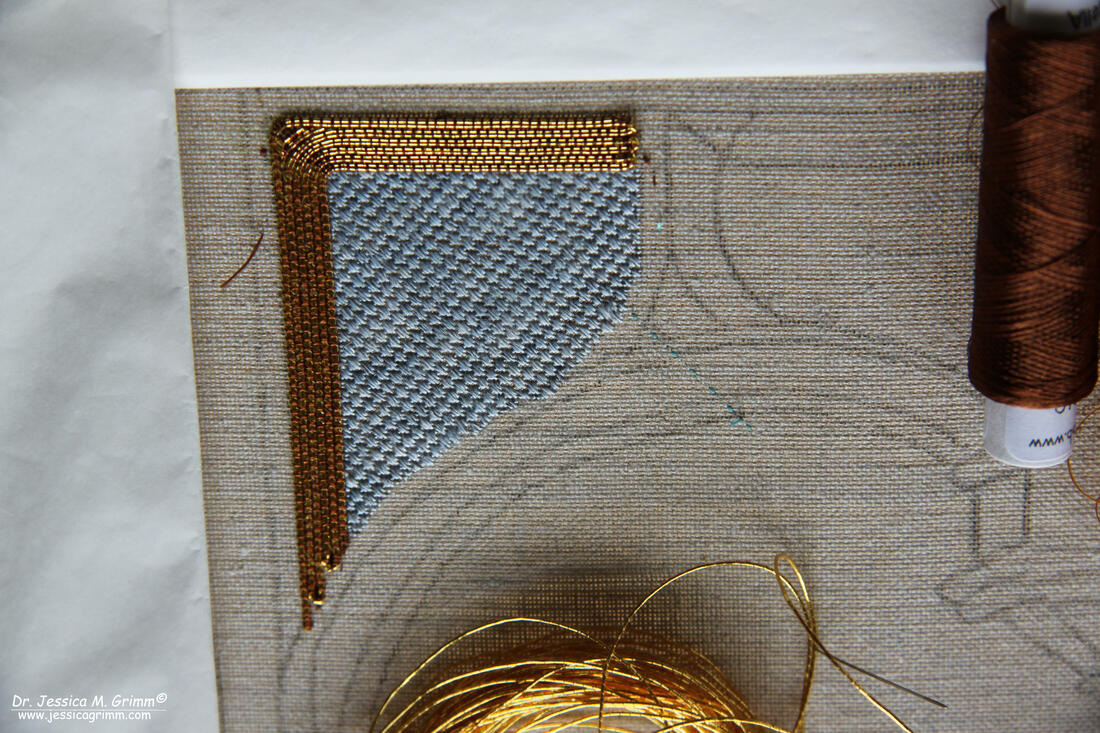

In this book, zardozi embroidery is called zari (metal thread embroidery). Badla is another form of metal thread embroidery associated with India, the Gulf region, Syria and Egypt. The later includes plate being used as a 'sewing thread' rather than being couched onto the fabric as is done in Western goldwork embroidery. As can be seen from the terminology above, there are many terms which refer to particular types of goldwork embroidery. This is due to the fact that 'the Arab World' stretches from Mauritania to Syria to Oman and Somalia. Regional differences are likely reflected in these terms. At the same time, as these distinct regions function within the cultural meta-system of the 'Arab World', techniques, materials and designs blend and influence each other. When I was researching medieval cope shields for my latest goldwork project 'On the shores of St. Nick', I saw that many had some kind of architectural frame going around the scene. I wanted one too! So I picked the one from a cope shield showing Abigail and David made around 1520-1530 in the Northern Netherlands. The piece is kept at the Catherijne Convent in the Netherlands and can be viewed in great detail online (click the image and watch 16 additional pictures which you can enlarge as well!). The pictures below come from this fantastic online catalogue. It is a beautiful and ornate piece. But when you really start to look at it, you will find some curiosities. Look for instance at the innermost columns (those with the spiral going around). Notice anything amiss? The base of the column is behind the outermost column, but the capital is in front of it!!! Turns out M.C. Escher wasn't that original :). A similar thing can be seen in the piece of St. Laurence: the floor tiles in the original are completely wrong perspective-wise. Why did the late-medieval embroidery designers make these mistakes? Well, the Renaissance had only started in Italy roughly a century before this piece was made. Interestingly, early Netherlandish art (1425-1525) developed independently from the movement in Italy. Wikipedia says: "The Netherlandish painters did not approach the creation of a picture through a framework of linear perspective and correct proportion. They maintained a medieval view of hierarchical proportion and religious symbolism, while delighting in a realistic treatment of material elements, both natural and man-made." And that's exactly what we see here. But that`s not all! The average medieval embroiderer was clearly not aiming for 'distinction' at the Regiis schola opere plumarii. Yup, that's Royal School of Needlework in Latin according to Google translate :). In this case, there are some issues with the padding. I've marked them with white in the picture on the right. Can you see the problem? The string padding runs in the same direction as the couched gold threads should run. That doesn't work at all. Imagine trying to couch down a round goldwork thread on top of a round piece of string? They will always try to get away from each other and roll. The solution? Fudge as you go. But it doesn't really work. Quite a lot of the definition is lost and it looks messy. But in a world with dark churches and only candlelight, it didn't matter. As long as it sparkled to the greater glory of God and the wearer, it was okay. P.S. Note that the original background drawing was different and more ornate? I love the fact that the embroiderer had a degree of freedom in stitching the design! Unfortunately for me, I did attend the Regiis schola opere plumarii (sorry, but I now like it better than the English name). I already sorted out the mess underneath St. Laurence's arm and I intend on sorting out this mess too. But it is a slow process. Especially as things are perspectively wrong, I really need to think a lot first, before I couch down any gold. The plan is to lay the gold in the direction of the architecture, instead of working strictly vertical. The above is the result so far. I am using House of Embroidery fine silk colour Forget me Not in a condensed Scotch stitch for the sky. The Japanese thread #8 is couched down with DeVere Yarns 6-fold silk colour Allspice. I really like how well this warm brown colour combines with the gold!

About four years ago, my mum discovered a little black velvet clutch with goldwork embroidery and white beads at a flea market. Now she has found another one! It is clearly of the same general type, but with another goldwork design. Let's have a closer look! The first clutch was covered in detail in this blog post. Contrary to the first clutch my mum discovered, I really like the embroidery on this one! The trellis is made with pearl purl #1. The junctions are covered with a cross-stitch using two pieces of rough purl #6. The trellis is completely filled with pretty little flowers. Each little flower is made up of four petals: a larger cross-stitch with two pieces of rough purl #6 with each 'leg' of the cross encased with a piece of bright check bullion #4. The border surrounding the trellis consists of rectangular shapes made of 9-10 parallel pieces of rough purl #6 encased by four pieces of bright check bullion #4. The rectangles are surrounded by more pearl purl #1 and pairs of large chips made of bright check bullion #4. The bag has clearly seen much love :). Especially the bright check bullion has come unwrapped in many places. This is such a rough thread that you can easily imagine how it got caught on clothing. There is also a spot in the middle, a little off centre, where the threads are heavily tarnished. This is precisely where the thumb of a right-handed women would rest when she holds her clutch.

As I never received any comments on the first blog post regarding these fascinating little bags, I asked some experts for help. First up was the curator of the Museum of Bags and Purses in Amsterdam. I was hoping that these bags are so common that she would be able to assess its provenance and age. Unfortunately, she couldn't as the bags have no label. However, she recommended asking Dr. Gilian Vogelsang-Eastwood of the Textile Research Centre in Leiden. As I've met Gilian years ago, it was really nice emailing my questions to her. Her suggestion was that these bags are not very old: second half of the 20th century and made by fashion houses for the tourist industry. It is clear to goldwork embroiderers that the embroidery on the bags is rather cheap and cheerful than exquisite. The construction of the bags is also rather simple and done with cheaper materials (see first blog post for details). |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed