|

The National Silk Museum in Hangzhou had a small number of embroideries made by several ethnic minorities on display. After last week's book review on the textile traditions of one of these minorities, the Miao (Hmong), I thought it a good idea to share my pictures with you! First up is an embroidered apron worn by women of the Dong minority. The Dong are matrilinear people from the south of China. The embroidery on this apron consists of brightly coloured satin stitches (possibly over a cut paper template) and some applique. The pattern is made up of stylised flowers and the sun symbol (probably the swirls; Chinese explanations at museums are notoriously vague ...). Other parts of the apron consist of strips of wax-resist dyeing. Unfortunately, the only thing stated on this apron is that it was worn by an ethnic minority from Guizhou province. What I understand from the museum's description is that this is a single panel and that several of these embroidered panels would make up the actual apron. Do you see all these white buttonhole wheels? There are also chain stitches and knots. I think they used chain stitches to create the star shapes on the left and the maple leaves on the far right. Quite a clever and visually pleasing piece, I think! This panel was embroidered by the Ge people who also live in Guizhou province and who are officially considered to be a sub-group within the Miao. This piece mainly consists of outlines stitched with fine and very regular chain stitches. There is also some back stitch and some satin stitch visible. This piece of clothing (called 'braces' in the description) was also embroidered by the Ge people. It is again covered with very regular chain stitches and interspersed with satin stitches. The regularity of both pattern and stitching is absolutely stunning! The last piece on display was an embroidered shawl made by the Miao. The geometric pattern is based on an old song and represents flower beds. The stitching is entirely done in a form of long-armed cross-stitch. This is even a better close-up of the flower bed pattern. The movement created with the stitching is absolutely sublime! Keep staring at it and see how many different patterns you are able to see :).

6 Comments

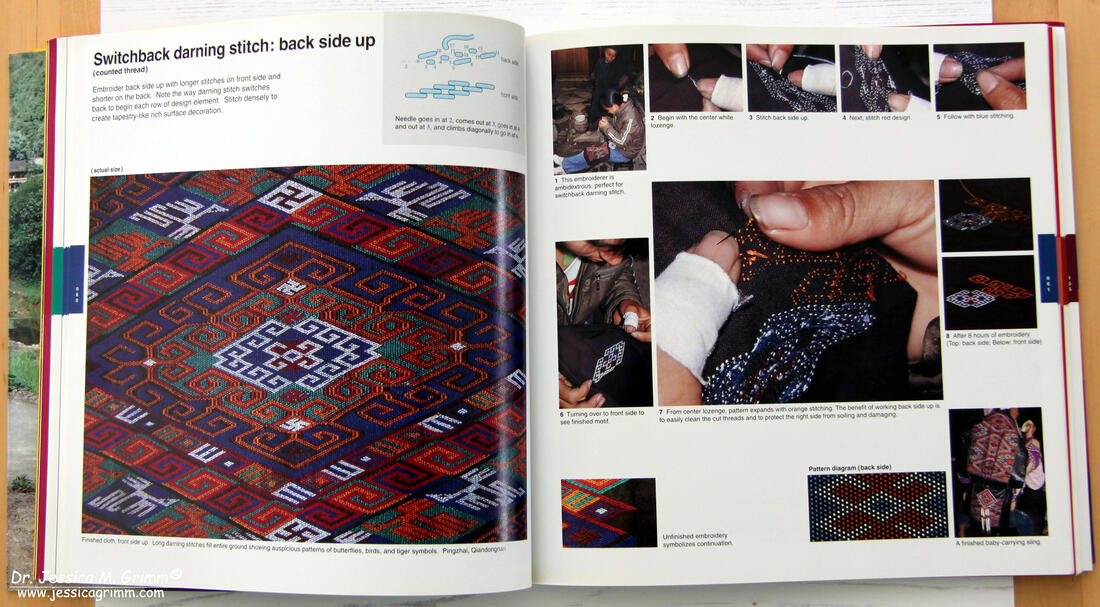

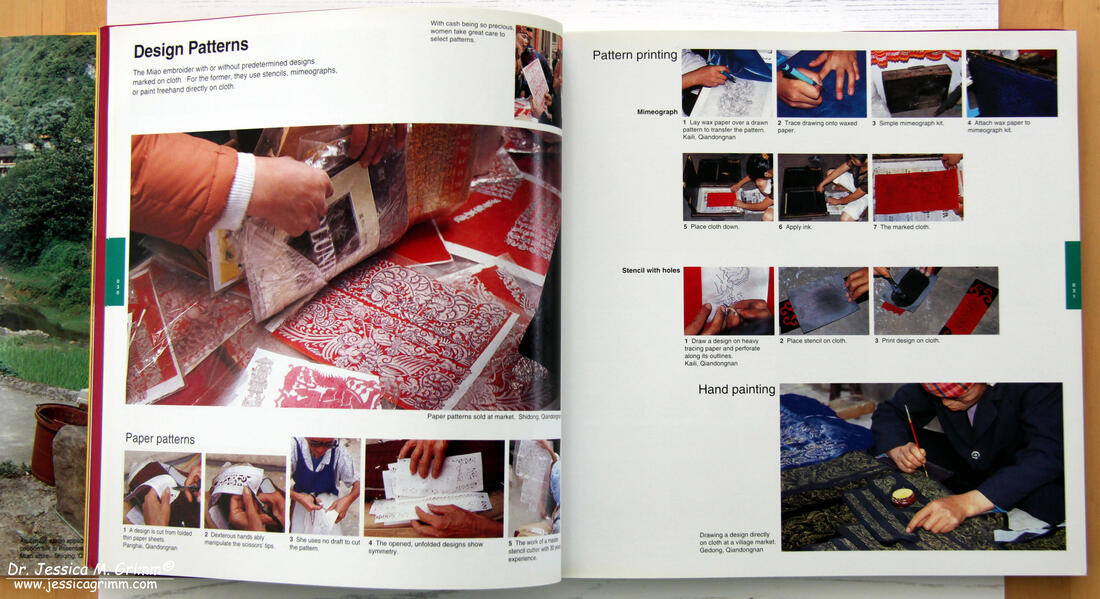

I was given this lovely book about ethnic embroidery from China by the lady who organised my teaching trip to China last year. This book on an interesting topic has a rather special and highly pleasing visual concept as well. Although it is not your classic project book, the step-by-step photographs and descriptions mean you can easily recreate particular stitches and patterns. Especially for those of you who are already adept at wielding a needle, there is a lot of 'new stuff' in this book which will make your hands itch. The book is written by Dr. Tomoko Torimaru, a Japanese woman who studied Chinese textiles at the University of Shanghai, China. She is the daughter and research-associate of her mother Dr. Sadae Torimaru. Together they have studied the textile traditions of the Miao and related ethnic groups for many decades. They are both well-known and respected textile researchers and deserve to be more widely known among Western embroiderers as well. Full details of the book: Torimaru, T., 2008: One Needle, One Thread: Miao (Hmong) embroidery and fabric piecework from Guizhou, China, University of Hawai'i Art Gallery, ISBN: 978-1-60702-173-5. And this is what a typical two-spread from the book looks like. Many detailed pictures with explanatory text. In this particular case, the darning stitch is worked from the back in order to protect the finished embroidery. One needs great skill to not make a mistake when carrying threads or otherwise the pattern on the front will show a mistake. There are several embroidery techniques detailed in the book where the embroideress works from the back to avoid soiling the finished embroidery. Throughout the book, you will learn about the myriad ways of pattern design and transfer. I am blown away by the fact that some paper-template cutters are so skilled that they do not need to make an outline drawing prior to cutting ... There are also many 'recipes' in the book for making starch and thread conditioner from local plants. You'll be amazed at how often the silk threads for embroidery are conditioned to behave during embroidery. I am always quite reluctant to use thread heaven or the like on my silk threads. I usually talk them into submission (with various degrees of success, I must admit). Another thing I was reminded by when reading the book from cover to cover, is how ingenious people are. We can be one heck of a clever naked ape! For the Miao, embroidering their folk costumes is typically done in between other tasks. When waiting or tending the family, for instance. There's often no ergonomic position to be had or good lighting. Slate frames or hoops for perfect tension? How about using your knees and thighs instead? And it is almost always an activity you'll share with other females. Knowledge transferred from mother to daughter. Underlining and taking pride in one's ethnic identity one peaceful stitch at a time!

Before we dive into more exquisite embroidery from China, just a little shout-out to the Fiber Talk podcasts. On Sunday, I had my second lovely conversation with Gary discussing my ongoing journey from craftsperson to textile artist, my trip to China, the reality of turning your skill into your business and so on. We laughed a lot and hope that you`ll enjoy the conversation too! You can listen via the player on the Fiber Talk website (were you'll find hundreds of other engaging podcasts with fellow embroidery people!) or you can watch the episode on FlossTube. In previous blog posts I have shown you the oldest pieces of embroidery I saw in China as well as beautifully embroidered rank badges. Today we will examine the court robes worn by the Qing emperor (AD 1644-1911) and his closest relatives. These lavish robes are decorated with the symbol of the emperor: the dragon. Hence their name: dragon robes. But there is more than just gorgeously embroidered dragons on these robes. After all, we are in China :). These robes are packed with meaning. Luckily, there was a very helpful picture in the National Silk Museum, Hangzhou pointing out the different motives and their meaning: The different symbols are arranged in three distinct circles. Around the neck you'll find the sun (life force) and the moon on the shoulders and constellation of three stars (the handle of the sign Ursa Major; illumination) and the rock (stability) on the front and the back. The next circle runs over the chest and features the axe (distinction between right and wrong) and double bow (dispensing of justice) on the front, as well as a pair of dragons and a pheasant (light and colour). The third circle at knee-level sports a pair of bronze sacrificial cups (courage and wisdom), waterweed (purity), grain (nourishment and sustenance) and fire (warmth and light). When the emperor conducted certain important ceremonies he would sit facing south. The major symbols on his dragon robe would then allign with the wider architecture of the Forbidden City: the sun on his left shoulder with the Altar of the Sun in the East, the constillation of the three stars on his chest with the Altar of Heaven in the South, the moon on his right shoulder with the Altar of the Moon in the West and the Rock at the nape with the Altar of Earth in the North. And this is the real thing: a dragon robe featuring nine dragons. This particular robe would have been worn by an imperial prince during the summer. The background cloth is imperial yellow silk only to be used by the emperor and very close relatives. Above is a picture of one of the dragons featuring in the third circle just above the seam. The dragon mainly consists of couched gold threads (Japanese thread) and accents in silk embroidery. The small motives surrounding the dragon are stitched with silk in satin stitch. Among these small motives are bats (left of the right hind-leg of the dragon), pairs of peaches (at the top of the picture, right above the head of the dragon) and flaming pearls (the couched roundel with red silk embroidery, left of the head of the dragon) and many clouds. The hem is decorated with ocean waves, mountains, coral and rocks. Here you'll see the tiny bats, peaches and clouds in more detail. I particularly love the bats. Aren't they geniusly stitched? They are tiny, but there is so much characteristic detail. Just look at the ears and the whiskers! The Chinese word for bat and for happiness are the same. Red coloured bats are even better as the colour red and the word for majestic/subleme are also the same. Bats depicted together with peaches confer the wish `May you live long and happy`. And here is a detail of the seam of the prince's dragon robe. I particularly like the way the circular wave in the middle is embroidered. Very effective shaded split stitch for the spiral, surrounded by satin stitched `white heads`. The design lines of the `white heads` are further defined by couching down a single gold thread. The vertical stripes at the bottom represent deep water. Stylished multi-coloured rocks rise from the waters. The ancient Chinese preceived the world as being surrounded by four oceans.

You can find more information on dragon robes and embroidered symbols in: Bertin-Guest, J. 2003. Chinese Embroidery traditional techniques, Krause Publications, ISBN 087349718-X. This book also explains the embroidery techniques in detail and comes with 16 (increasingly difficult!) designs to work yourself. When I was teaching embroidery in China last year, I saw so many beautifully embroidered items. Far too many to put into one blog post. Today we will explore a very distinctive form of embroidered items: rank badges. Those square pieces of densily embroidered cloth that were sewn onto the formal dress of Qing-dynasty (1644-1911 AD) court officials. The Qing emperors were the last house to rule China. They were not native Chinese, but rather a nomadic minority from Manchuria. Due to a power vacuum in the middle of the 17th century they were able to take over the dragon throne. Native Chinese viewed these newcomers as barbarians. Vice versa, the Manchu viewed the Chinese as too refined. Discrimination and mistrust were the result. In an attempt to at least minimize discrimination amongst the court officials and to legitimize their new dynasty, court dress was completely renewed by the new emperor. Modelled on Manchu dress, but with strict rules on who could wear what and when. As the imperial administration became ever more complex, it was necessary to be able to easily distinguish people's place or rank in the system. There were nine ranks of civil officials all sporting a different bird on their rank badge. From first to ninth rank these were: Manchurian crane, golden pheasant, peacock, wild goose, silver pheasant, egret, mandarin duck, quail and paradise flycatcher. The badges (called pu zi) were sewn onto the surcoat pu fu, or 'coat with a patch' and worn over the formal court robes. The badges would be sewn onto the front as well as onto the back. That's why a pair always consists of a 'whole' one for the back and a 'split' one for the front. Why did they use birds to differentiate between civil officials? As always, everything depicted has more than one meaning for the Chinese. Birds collectively were seen as a symbol of literary elegance. Additionally, the crane was associated with happiness and longevity. The wild goose and the mandarin duck represented loyalty; not an unimportant quality for a court official. Military officials wore rank badges too. Instead of birds, animals associated with courage and ferocity adorn these badges. Again there are nine ranks and from first to ninth rank these are the animals depicted: qi lin (a mythical creature with the head of a dragon, scales on his body, the legs of a stag and a bushy tail), lion, leopard, tiger, bear, panther, rhinoceros and sea-horse. Lower ranks of the imperial nobility were also permitted to wear the military rank badges. The wives of military and civil officials adorned their formal dress with rank badges too. Rather than being part of the court, they would wear their dress with badges during important social occasions such as marriages. Besides his official empress, the emperor had many secondary consorts and concubines. They were ranked as well. And with so many potential partners, he had many offspring too. The emperor, his sons, first-rank princes, second-rank princes, third-rank princes, fourth-rank princes, imperial dukes and other non-imperial nobles wore round rank-badges displaying dragons. The number of dragons you could wear depended on your rank. As did the type of dragon you were permitted to wear: front-facing dragons were higher in rank than side-facing dragons. And five-clawed dragons (long) were higher in rank than four-clawed dragons (mang).

If you have enjoyed reading about official court dress, I can highly recommend the book 'Imperial Wardrobe' by Gary Dickinson and Linda Wrigglesworth (2000, ISBN: 1-58008-188-6) for further reading. This is the revised edition of an original from 1990. Two cents for your thoughts when you read the above blog title. Highly likely that you now have a picture of these hyper-realistic silk embroideries in your mind :). But that's not what we are going to explore in this blog post. Chinese embroidery is so much more! There's the intricate and colourful embroidery from the many ethnic minorities we will explore in a future blog post. And then there are these magnificent dragon robes worn by the emperor and his close relatives. Equally food for a future blog post. But how did it all began? A question I never really asked myself before I went to China. As an archaeologist I am all too aware that the evidence we have for really old textiles adorned with embroidery is scant. You need very favourable preservation conditions for them to survive. So the mantra instilled in me as an archaeology student: absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence, holds very true in the case of ancient textiles. But traveling to China and talking to Chinese embroiderers, the question of how it all began is paramount to them. The humiliation at the hands of the Western powers in the 19th century is still a national trauma. Being the inventor of something which was subsequently adopted by the West, thus counts! The National Silk Museum in Hangzhou has a very modern exhibition on the textiles form the Silk Road. The exhibition includes many textile fragments from recent large scale excavations of tombs. A new exhibition titled 'Countless stitching and marvellous threads' was opened when I taught my workshop at the end of October. Unfortunately, this exhibition has no captions in English (unlike the Silk Road exhibition which is entirely bi-lingual). From what my phone was able to translate, the new exhibition focusses on stitches and how they emerged and developed. Starting with archaeological remains and ending with modern embroideries by contemporary masters. Taking pictures of the embroideries on display posed its own problems. The lighting was understandably dim and flash equally understandably not allowed. Usually not a problem when you are patient and have a steady hand. What was a problem, was the bad quality glass used for the display cases. And the fact that they were very (I mean VERY) dirty from the touching of countless hands. China is this delightful combination of a developing country and a highly digitally developed world nation. This means that they laughed at me when I explained that in my rural village of 1200 people, probably 600 or so don't have a mobile phone, nor an email address. Digital 'illiteracy' is high here and not only among the elderly. At the same time, all 1200 of us would shake our heads in pity at the many Chinese who don't have a private toilet in their home and need to use the public toilet. How to use a museum is something they are in the process of figuring out :). Let's explore the embroideries! The oldest embroideries on display, date to the period of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) and the Northern Dynasties (386-581 AD). However, in the publications on embroidery I bought at the museum, it is stated that embroidery already existed in the Xia dynasty (2200-1800 BC). But, this is from oral tradition rather than archaeological finds. The first archaeological evidence seems to date from the late Shang dynasty, around 1300 BC. The above fragment dates from the much later Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) and shows longevity symbols stitched with several colours of silk using chain stitch on a red silk background. This small fragment is all that is left from an all-over embroidered female dress. Other embroidered items include a pair of red socks from the first-third century AD. The stitch used seems to be very fine chain stitch. And here is a piece with goldwork embroidery (couching) depicting animal masks and dating to the Northern Dynasties (386-581 AD). This very large piece depicting lions dates from China's golden age, the Tang dynasty (7th century AD). This lovely piece is an embroidered leather pouch with twill damask and samite border. It dates to the Liao dynasty (907-1125 AD). The upper part is a twill damask border, the middle is of leather, completely covered with chain stitch embroidery, with different patterns on each side: birds, butterflies and peonies on one side and flying birds and hunting motifs on the other.

P.S. If you are interested in the history of Chinese embroidery, I recommend the book 'Silken Threads. A history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam' written by Young Yang Chung in 2005, ISBN 0-8109-4330-1. This is an epic volume with beautiful pictures and of the highest scientific standard. Jetlagged and with a nasty cold, but full of wonderful stories about my recent teaching trip to China, I sluggishly slump behind my laptop. To add insult to injury, my dearest coffee machine died on me when we got home from Beijing on Saturday night. I nearly killed someone this morning who carelessly suggested that I could easily survive on instant coffee until my beloved machine gets repaired... Let's talk of happier things, shall we!? Packing my 24 days in China into one blog post might be a little too much :). Instead, I will write several posts in the coming weeks on my adventures in the far East. We'll start today with the actual teaching. I arrived a few days early in Shanghai and was picked up by Edith, a textile enthusiast from Hong Kong, who had organised the workshop. We immediately got on really well! We decided to take the bus to Hangzhou; my first taste of the excellent public transport services in China. After being dropped off in the centre of Hangzhou, we took a taxi to the hotel situated near the famous West Lake. As Bad Bayersoien - Hangzhou takes nearly 24 hours, I was ready to slip between the covers in my lovely hotel room. After a delicious breakfast the next morning, we crossed the street to visit the National Silk Museum. The museum is quite large with several buildings housing different exhibitions related to silk. The buildings sit in a beautifully landscaped park. Exploring the ground floor of the silk road exhibition alone took me about two hours! In the afternoon, I decided to take a walk and explore the famous West Lake. As it was the weekend, many Chinese holiday makers had the same idea. The place is famous for getting your wedding pictures taken and the whole area is an important inland holiday destination. I ended up visiting a Buddhist temple, the tombs of some revolutionaries and ended with Jasmin tea overlooking the lake. As there where not many other Westerners, the Chinese looked upon me with great curiosity :). On Sunday, we prepped the classroom for the workshop starting on Monday. I met my assistant and translator Clover who has studied weaving in London. She did a great job translating my English into Chinese during the workshop! And in between, we ate :). Not only breakfast was a treat, the local eateries were fabulous too! Me using chopsticks for the first time was hilarious and I must confess that I don't miss them... On Monday, the teaching started. The group of students was very divers. I had museum staff, art teachers, fashion designers and even two craftsmen from Tibet. They were all very eager to start! Although the official classroom was in the basement, we decided to use the lovely weather and stitched outside a lot. Sitting in front of an old sericulture farm was a favourite with all of us until the mosquitos found out about it too... We strung a line and hung up the result of the previous day to talk about the experience. I was very impressed with my students as most of them had finished their projects overnight! However, getting them to critique their work publicly or express their experiences with the particular embroidery technique, wasn't easy. Other favourite stitching spots were the cafe... ...and the gallery of the fashion building. Those large windows were fantastic. When teaching the goldwork leaf on Thursday, I discovered a mistake with the scale of the leaf. Oopsy! Time for a last-minute change: add some chipping to the original design and all was well again. It shows that no matter how well you prepare, mistakes can always happen. Adapt and carry on! We ended the day with a Chinese high-tea organised by the students. They had brought all sorts of delicacies for me to try. Yummy! The schedule on Friday and Saturday changed a little. We had the opportunity to pair my talk on medieval embroidery with that of a local master embroiderer on Friday. We had all hoped that she would talk on the techniques she used in her embroideries or the thought process that went into them. Unfortunately, she didn't. It was more a sales talk. However, some of her work was really nice and unusual. It showed that she also experienced difficulties with branding her work as art. My talk went really well. The museum did record it on video and as soon as I know where it is available, I will let you know. If it does not become available, I will put up the original presentation and let you know where to find that. However, it is much more fun to hear a Dutch person talk in English and have that translated into Chinese by Clover :). As one afternoon of the original five-day workshop was high jacked by the presentations, we decided to meet again on Saturday morning (in the original plan I would have given my presentation on Saturday). I was completely blown away by the fact that quite a few students had completed all four projects! That's the best praise a teacher can get. It shows that they really enjoyed themselves and loved the tasks I had set them. Those six days were immensely gratifying and I really had a blast! Seeing people figuring things out and going on helping others is such a great experience. I really hope they can implement the things they have learned in one way or the other.

After having had a sore arm for three days thanks to 1ml of immunisation fluid, I was hit hard again. Obtaining a visa for China will set you back a whopping €286! So when I received my passport back I was hoping for something sparkling. A little gold dust perhaps? Nope. It is a rather ordinary looking sticker.... Luckily the mailman brought me some promotional material concerning the museum and Hangzhou to cheer me up. Especially the museum and the West Lake look very pretty! Preparing for China means I don't have much time to do some stitching. I still need to make instructional videos from the footage I shot whilst stitching the class samples. This means I am learning to use Adobe Premiere Pro and video platform Vimeo. Quite fun actually. The first eight videos concerning the crewelwork pomegranate are up there. And then there is another major thing that gets in the way of stitching: the garden. Whilst the rest of Germany and indeed most parts of Western-Europe had a severe drought this summer, the Alps had a good summer. This means that our 'Belle de Boskoop' is having a bumper crop. Normally, this tree has a hard time coping with the harsh alpine climate and only gives us miniature very hard green fruits. However, it seems we now have a climate change winner here. My kitchen turns into an apple processing plant most days. So far me and my husband have made several pies, Lithuanian apple cheese (google it!) and apple sauce. On top of that, we have the larder full of beautiful pumpkins and herbal teas. I am very grateful for nature's bounty!

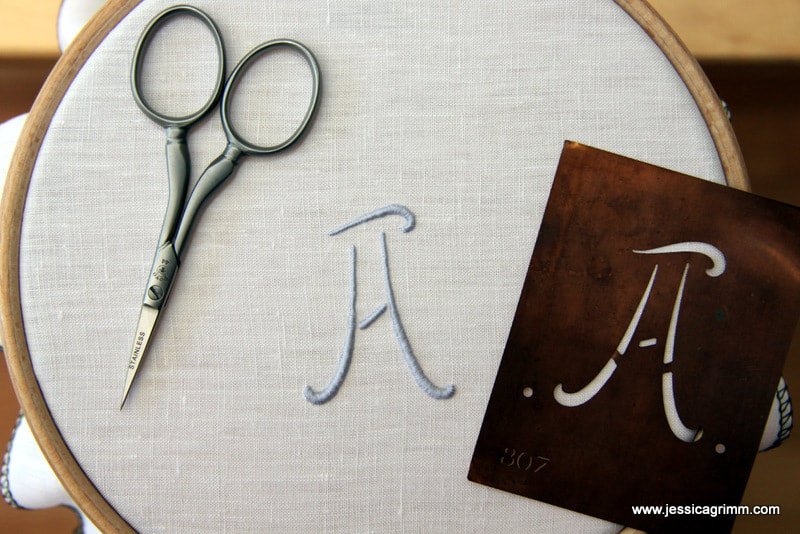

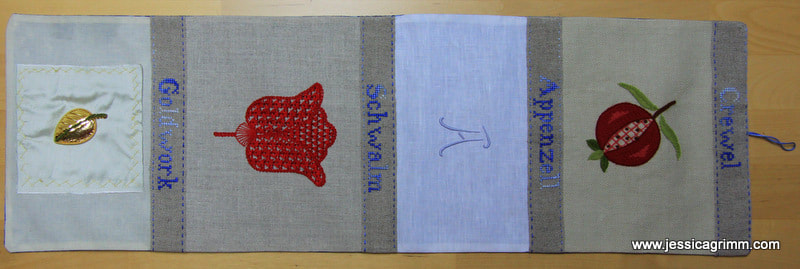

Back to making more apple sauce :)! For my upcoming teaching trip to China, I was asked to demonstrate several European embroidery techniques. Finding the techniques was not a problem, after all we have a rather rich embroidery tradition. But what to do with the stitched samples? And how to manage pace in a medium-sized diverse group of students? I came up with the idea of making a band sampler or a 'pronkrol' (pronken = to show off) as they are called in Dutch. This is a type of band sampler which became popular in the late 19th and early 20th century and was worked at private boarding schools for girls. As French was the preferred language of the well-to-do, these band samplers are often called 'Souvenir de ma Jeunesse'. What will my students learn? They will start with making a pomegranate with a few key embroidery stitches used in Jacobean crewel embroidery. Then they will explore Schwalm embroidery. This is a drawn-thread whitework technique from the Hessian region of Germany. Students will fill a classic tulip design with tulip patterns. Next up is a monogram using the fine whitework technique from Appenzell in Switzerland. And last but not least, they will learn couching, padding and cutwork to produce a goldwork leaf. Each technique will be separated by a small linen band sporting the name of the technique in cross stitch. After all, the humble cross stitch plays a very significant role in European embroidery. Both past and present. And these bands are great for students to work on on their own when I am not immediately available to solve a problem. The finished pronkrol will serve the same purpose as the antique ones did: show off a student's work. In the old days, the pronkrol would also inform the prospective mother-in-law about the housewife qualities of the bride-to-be... This is what the finished pronkrol will look like: I am very much looking forward to this great adventure. Not only will I be passing on time-honoured knowledge to new students, but I will also have the opportunity to learn from the Chinese about their magnificent embroidery culture!

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed