Saint John and his identical twin: mass production of goldwork orphreys in the late-medieval period7/9/2020

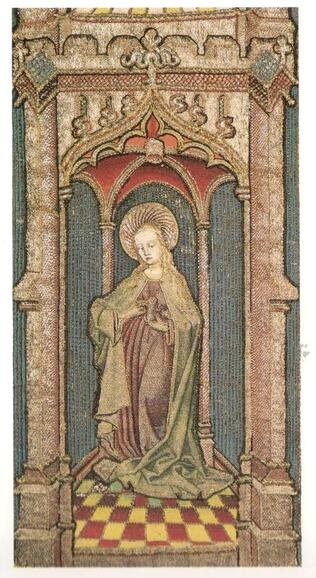

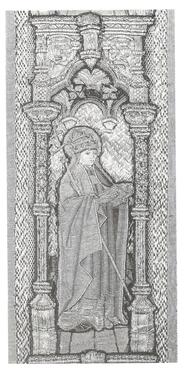

Last year I visited the Dommuseum in Fulda and was struck by a particular goldwork orphrey. It sported a beautiful rendition of Saint John in or nue with a rather unusual background. Not one of these typical golden backgrounds with architectural features and a cloth of gold in diaper couching. Nope. His background consisted of blue silk satin stitches with some basic architectural features and less gold. What was going on here? There wasn't much information displayed in general in this museum and the information on Saint John was even more basic. But this wasn't the end of the story. Those who have watched my latest FlossTube with the Acupictrix video on Vimeo, already know that I found Saint John's identical twin in a book on the Frankfurter Domschatz. But that's not all. Here comes the rest of the story.

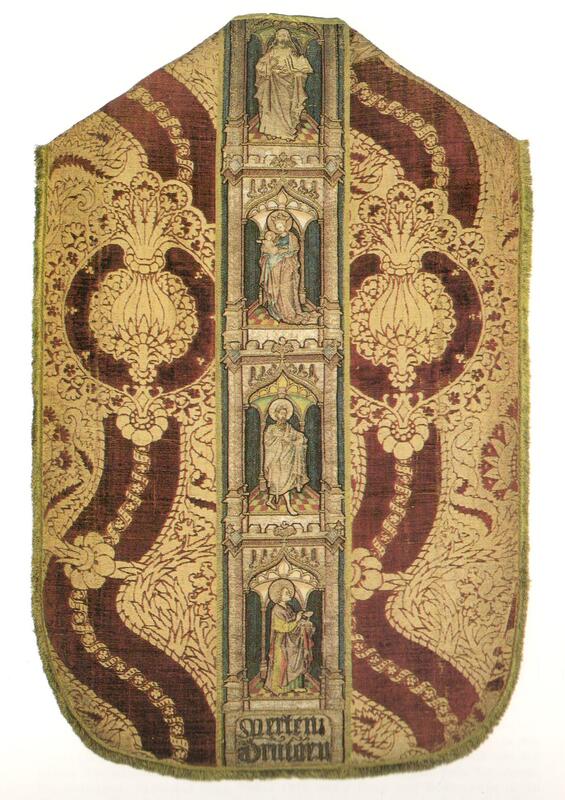

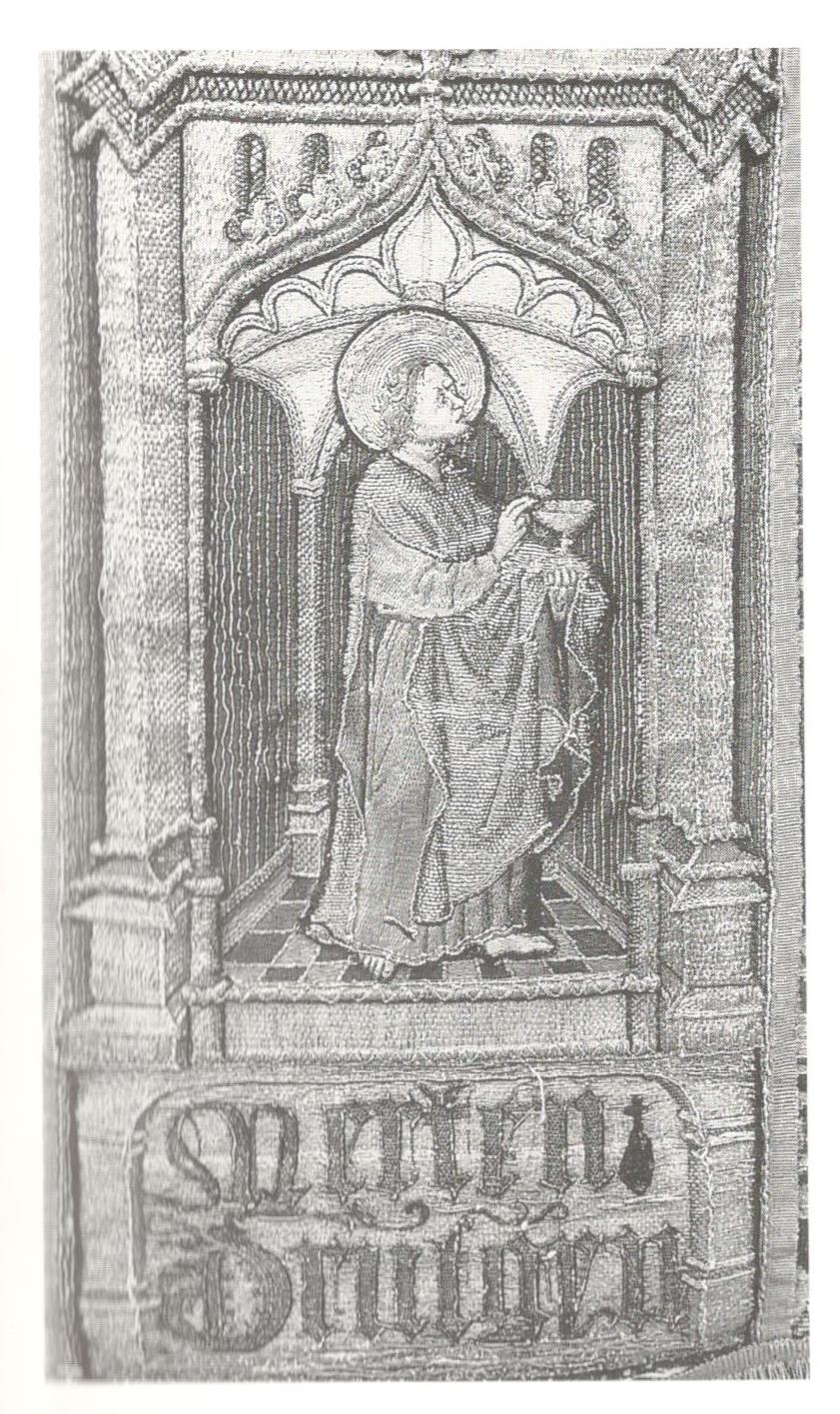

The chasuble that sports the identical twin of Saint John in the Frankfurter Domschatz is part of a set consisting of one chasuble and two dalmatics. The cope, which would have made the set complete, is missing. Although the set is now housed in Frankfurt, it probably originated in a church in 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands. Below the orphrey with Saint John are the names 'Merten' and 'Drutgen' stitched. The beneficiaries of this set of vestments. Merchant and member of the city council, Merten Moench/Maarten Monicx and his wife Drutgin von der Groeven. Merten was born in 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, but his wife was from Cologne. She died in AD 1451 and he died in AD 1466. Maarten likely donated the vestment set in 1460 to a church in his hometown of 's-Hertogenbosch.

The chasuble is made of red velvet shot with goldthreads. It is one of these famous red velvets made in Florence, Italy sporting pomegranates. The orphreys on the front show: Paul, Peter and Mary Magdalene. The ones on the back show: God, Mary with child, John the Baptist and our Saint John. All of them sport high-quality or nue figures set in a golden architectural background with blue silk stitches with a similar tiled floor stitched in yellow, red and green silks. Whilst the figures look very Dutch, the backgrounds don't. The blue vaguely reminds of the 'Kölner Borte'. These were mass-produced woven orphreys that sometimes showed additional stitching for the details.

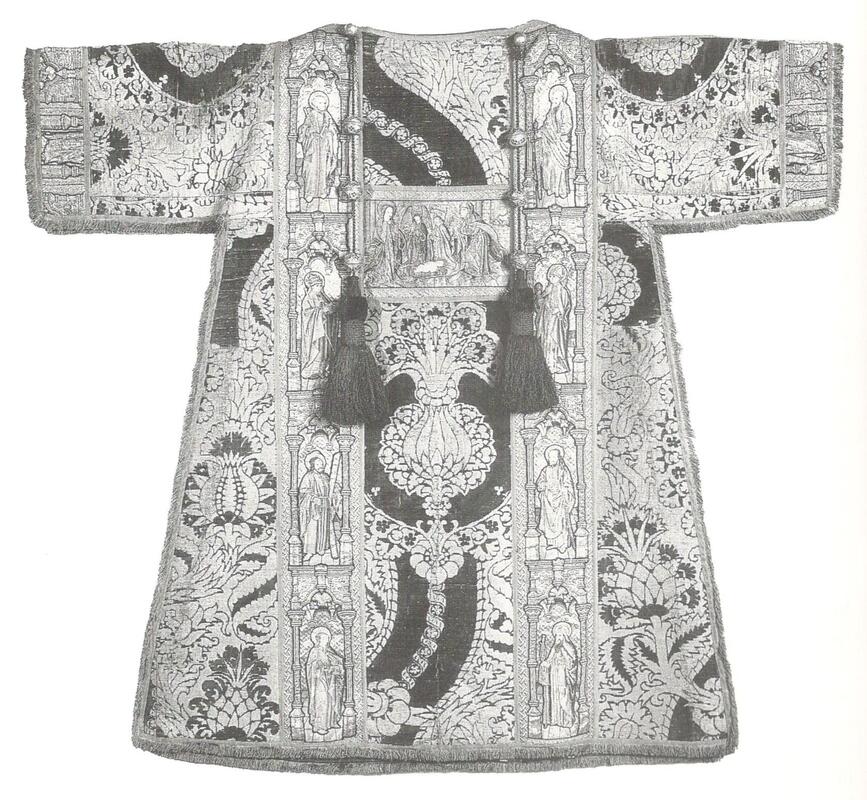

The two dalmatics are made of the same red velvet. But this time the orphreys are 'right'. High quality or nue figures sitting in a proper golden background so typical of the Dutch style.

What is going on here? We know from the historical records that the vestments were extensively restored in 1842/43 by the painter Edward Steinle and a parament maker and his two daughters from Cologne, with the help of another painter and conservator, Johann Anton Ramboux. It took them about a year to clean the vestments up and make them presentable again. They were paid 100 Taler for their work. That's about €4860 in today's money according to Google. I really hope they had additional income ... Anyway, although the vestments were extensively restored, the difference in backgrounds between the chasuble and the dalmatics is a medieval one and not the result of these restorations.

How does the single orphrey from Dommuseum Fulda fit into this story? As this orphrey has the same figure and background as the ones on the chasuble from Frankfurt, he is very likely part of the original set of vestments donated to the church in 's-Hertogenbosch. Beneath the original orphrey, another coat of arms is displayed. On the chasuble, the names of the beneficiaries are stitched beneath the orphrey of Saint John.

Looking closely at the figures on the chasuble, we see that they either look to the left or to the right. Furthermore, the orphreys are significantly wider than those on the dalmatics. This is a typical convention. Orphreys on a chasuble, but also on a cope, are wider than those on a dalmatic. The orphreys on a cope sit opposite each other at the front when the cope is being worn. The orphrey figures face each other: one faces to the right and the other faces to the left. This means that both the orphreys on the chasuble and the single orphrey from the Dommuseum Fulda were originally made for a cope. God would have sat opposite of Mary with child, Peter and Paul, Mary Magdalene and Saint John and John the Baptist is missing his partner in crime.

Now, this can mean several things:

1) Merten and his family were merchants with connections to the (Southern) Netherlands. They knew this type of goldwork embroidery well and valued it. Getting it from the Netherlands instead of opting for locally produced 'Kölner Borte' shows that these vestments were quite valuable and perfect to show off. 2) They were able to lay their hands on a number of loose orphreys and figures from the Netherlands and velvet from Italy. 3) These orphreys, figures and precious velvet were turned into vestments in Cologne by local craftsmen. These saw the 'complete' Dutch orphreys and worked orphrey backgrounds in a similar style, but with local influences to go with the loose Dutch figures. Names and coats of arms were added to make clear who bestowed these riches onto the church. 4) Orphreys intended to go onto a cope were instead applied to a chasuble. Or were they moved from a cope to the chasuble between AD 1460 and AD 1842/43? Does Saint John from the Dommuseum Fulda come from the original missing cope or copes? Or were so many figures bought at the same time and turned into 'Cologne-style' orphreys by the same workshop and then spread within Germany? Is the orphrey of Saint John in the Dommuseum Fulda the only remnant of a whole different set of vestments made in Cologne? One way of finding out is by identifying the coat of arms on the loose Saint John orphrey. I intend to write to both museums to ask if they know more. So exciting! I will keep you posted. Literature Fircks, Juliane von (2010): Serienproduktion im Medium mittelalterlicher Stickerei - Holzschnitte als Vorlagenmaterial für eine Gruppe mittelrheinischer Kaselkreuze des 15. Jahrhunderts. In: Uta-Christiane Bergemann, Annemarie Stauffer (Eds.): Reiche Bilder. Aspekte zur Produktion und Funktion von Stickereien im Spätmittelalter. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 65–82. Stolleis, K., 1992. Der Frankfurter Domschatz Band I Die Paramente. Kramer, Frankfurt.

10 Comments

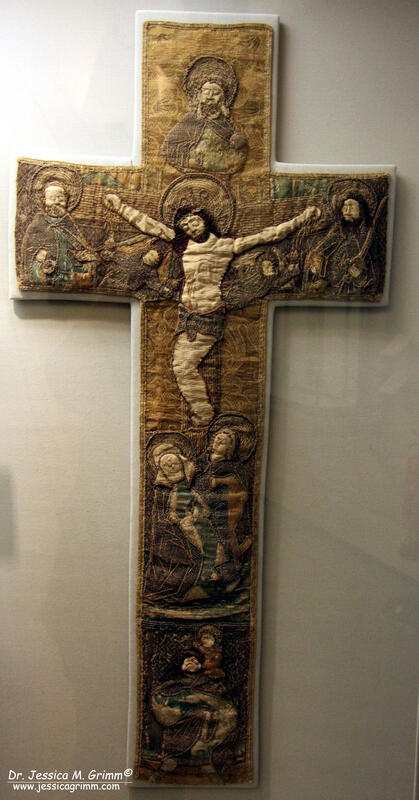

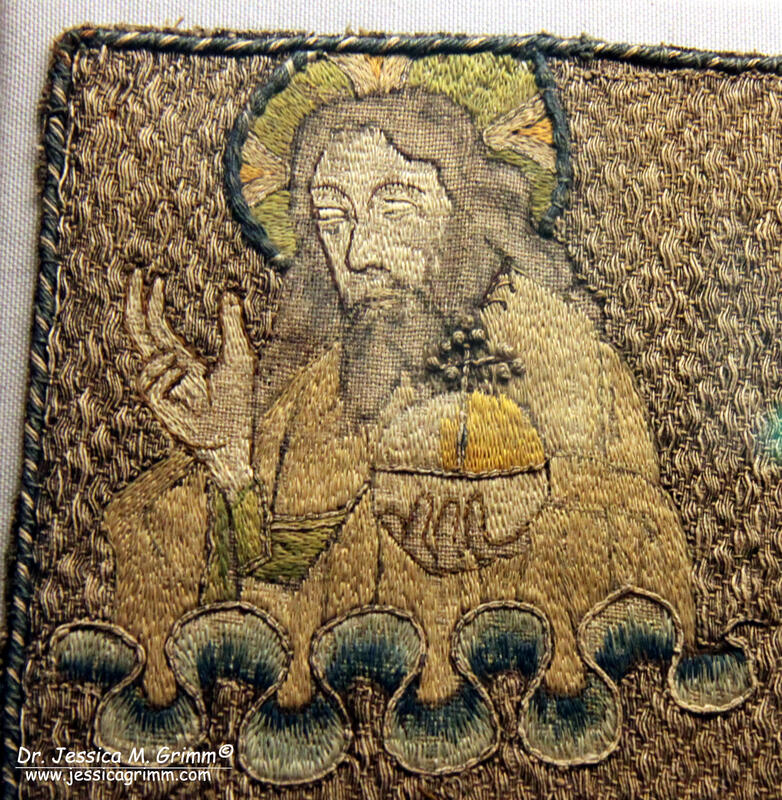

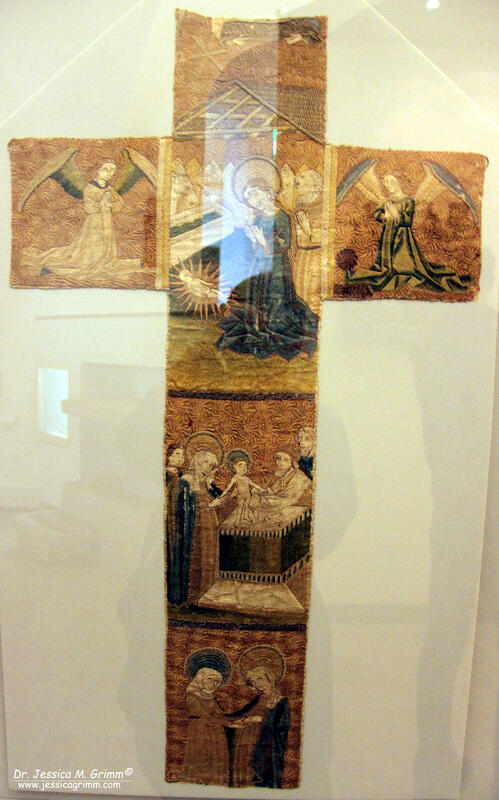

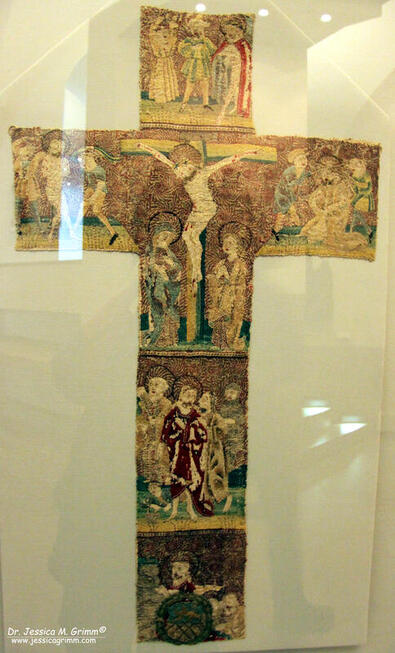

Last week, I showed you the vestments from the 17th and 18th century on display at the Dommuseum in Fulda. This week we will have a look at the medieval ones. Although the lighting was much better in this part of the exhibition, the glass of the showcases posed a huge problem when photographing the pieces. And to make matters worse, the warden revoked my permission to photograph. Nevertheless, I have a hand-full of nice pictures of very high-end goldwork and silk embroidery to share with you! First up are two pictures of an embroidered cross which would have adorned a chasuble. These embroideries were so precious, that they were mostly re-used on a new vestment when the old one was worn. In this case, the embroidery is a little special: it is raised embroidery. We often associate stumpwork embroidery with 17th-century England. In this case, however, the embroidery was done around 1500. The exact provenance was not stated, but these stumpwork embroideries were all made in the German-speaking parts of Europe. The most exquisite examples can be found in Mariazell, Austria. Here the figures stand about 3 cm proud of the background fabric! In the detail picture above, one can clearly see that the faces of both Peter and Jesus are padded. Jesus's ribcage is defined with a piece of string padding. The whole figure of Jesus seems to be somewhat padded. And the flesh-coloured fabric looks quite stiff and a bit like paper or vellum. And here we have two depictures of God from two different late-medieval chasuble crosses. Unfortunately, no further information was displayed for these two. Or maybe I forgot to take a picture ... I quite like these two. The clouds remind me somewhat of Chinese embroidery on the imperial Dragon Robes. Last up are these two. They are chasuble crosses embroidered around 1480. No provenance is given. These two caught my eye as the embroidery techniques used are quite different from the other vestments on display. No or nue here; the figures are stitched in silk using long-and-short stitch. In this detail shot, you can see what I mean. No or nue for the figures here. Instead, there is meticulous tapestry shading on the clothing (i.e. silk shading strict vertically instead of naturally). And the couching patterns for the goldwork threads in the background are so full of movement and quite different from the strict geometrical patterns seen in the late-medieval vestments from the Low Countries. I had a strange feeling that I had seen this before. And luckily for me, my mind sometimes does a good job :). Instead of needing to go through my thousands of pictures taken at museums, I knew at which museum I had seen this: the Diözesanmuseum Brixen, Italy. This late-15th-century (same date as the one from Fulda!) chasuble cross has a similar couched background. And most of the figures are stitched in tapestry shading rather than or nue (Mary being a notable exemption). So maybe the chasuble cross held at the Dommuseum Fulda has a more southern origin?

Being able to make these connections only works when I am allowed to take pictures. As lighting conditions or the way things are exhibited often do not permit studying the embroidery with the naked eye, my pictures are a great help. The camera is able to pick up details even when lighting is poor. I can zoom while taking a picture and again when looking at my pictures on the computer. Applying filters will tell me even more about the way things were made. It is therefore always very sad when the taking of pictures is not permitted. As long as you do not use flash (or use another source of light such as your phone!), you are not damaging the exhibits. And me taking pictures of the exhibits as is, has other benefits too. I don't need to make an official appointment for which museum staff needs to 'host' me (they have better things to do) and I don't need to handle the exhibits either. Some museums argue that by taking photographs and publishing them in a blog or on social media will mean fewer people will actually visit the museum. Really? I have the sneaking feeling that more people will visit a museum when they know what is on show. Especially museums with a wide range of exhibits of which textiles are only a small portion. The museum's website often does not specifically state that there are gorgeous embroideries on display (they are a somewhat neglected category, especially when in competition with bling made of precious metals) which might interest the curious embroiderer. And I know that several of my readers have visited museums which featured in my blogs. I have been guilty of doing the same. Maybe we should start mentioning these things to staff on duty when visiting a museum after reading a blog or seeing a picture on social media. What do you think? A couple of weeks ago, I visited the Dommuseum in Fulda. I knew from their website that they had at least some embroidered vestments. Little did I know that they had quite a lot of them! And when I asked if I would be allowed to take pictures, the clerk on duty said that he didn't mind me taking pictures. Unfortunately, he was quite a character and rather unpleasant. Half-way through the exhibition, he told me to stop photographing. No reason was given. Lucky for you and me, I had been able to take quite a few pictures before I was told to stop :). Enjoy the bling ... The above short video was shot with my phone. What you see here is one of the rooms where the vestments are shown. There are several of these large displays. They are reserved for the 'younger' vestments dating to the Baroque and Rococo (17th and 18th century). The vestments are shown in a kind of altar setting interspersed with other liturgical objects. Sets of matching liturgical vestments (cope, chasuble and dalmatic) are grouped together. As you can see the lighting is rather sparse. And the fact that most pieces are placed at a distance from the glass wall, makes studying them almost impossible. The written information was mostly limited to the name of the vestment, the date and the person who paid for it or for whom it was made. Not ideal for the curious embroideress! That said: the dim light and the 'scenic' placement of the vestments did give a good idea of how these gold embroidered vestements would have sparkled all those centuries ago. And that is an impression not many of us get to see nowadays. After all, how likely would it be to sit in a church service in the semi-dark (safety hazard!) with enough senior clergymen present (they are thinly spread these days!) that a full set of these antique vestments (museum people in uproar!) can be worn? And this is a picture of the same display made with my Canon digital camera (no flash, just a very steady hand). On the far left, you'll see a yellow cope behind a yellow dalmatic and maniple. They belong to the so-called Harstallscher Goldornat made in 1802 for the last Prince-Bishop of Fulda Adalbert von Harstall (1737-1814). The vestments are made of silk and gold brocade with some goldwork embroidery. Prominently in the middle of the picture are some red vestments. From the left: chasuble, stola, cope, palla, bursa, pink chasuble, pink stola and dalmatic. They belong to the so-called Roter Schleiffrasornat made in 1702 for Prince-Bishop Adalbert von Schleiffras (1650-1714). It is the oldest complete set of vestments in the museum. The vestments are made of silk and heavily decorated with goldwork embroidery. Detail of the cope hood of the Roter Schleiffrasornat. And this exquisite piece of goldwork embroidery can be found on the hood of the cope belonging to the Weisser Buseckscher Ornat made in 1748 for the Prince-Bishop Amand von Buseck (1685-1756). The fact that Amand was very good at drawing and a sponsor of the arts is probably reflected in the high quality of the padded goldwork on his vestments. Amongst all the bling I discovered what looks like a 17th-century casket of some sorts. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't take decent pictures of it. And there was no information on the piece either. But since I know that there are several 'casketeers' reading my blog, I am including it here anyway.

That's quite enough bling for today me thinks! Although it is quite difficult to see the beautiful goldwork embroidery up close due to the way the pieces are presented, the museum is well worth a visit and even a detour when you are in the area. Especially as they have some even greater embroidered treasures dating to the Middle Ages. But that's for another blog post ... |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed