Saint John and his identical twin: mass production of goldwork orphreys in the late-medieval period7/9/2020

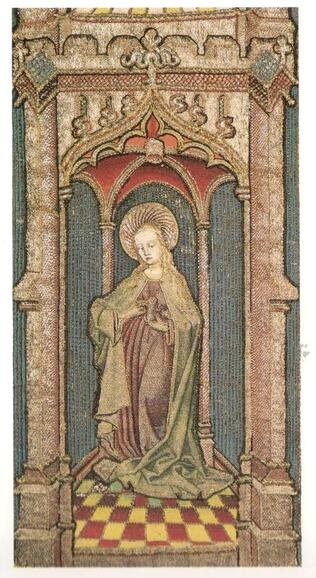

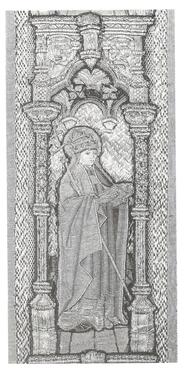

Last year I visited the Dommuseum in Fulda and was struck by a particular goldwork orphrey. It sported a beautiful rendition of Saint John in or nue with a rather unusual background. Not one of these typical golden backgrounds with architectural features and a cloth of gold in diaper couching. Nope. His background consisted of blue silk satin stitches with some basic architectural features and less gold. What was going on here? There wasn't much information displayed in general in this museum and the information on Saint John was even more basic. But this wasn't the end of the story. Those who have watched my latest FlossTube with the Acupictrix video on Vimeo, already know that I found Saint John's identical twin in a book on the Frankfurter Domschatz. But that's not all. Here comes the rest of the story.

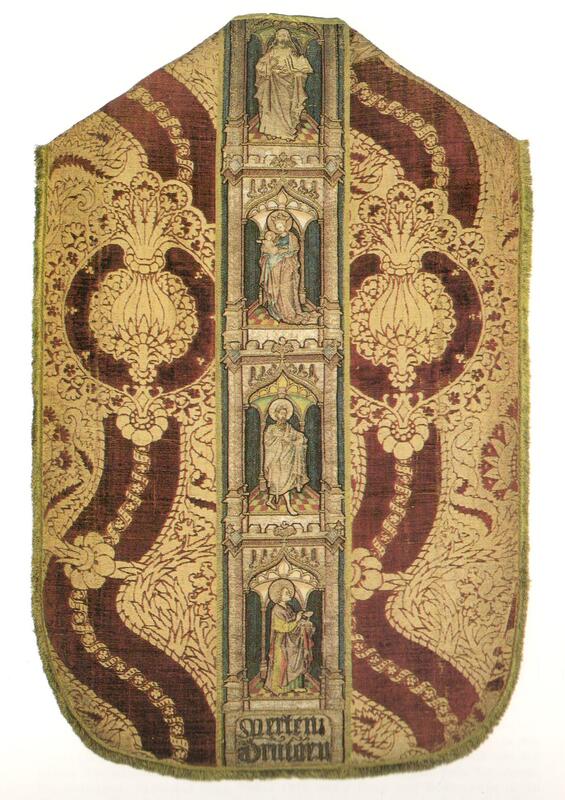

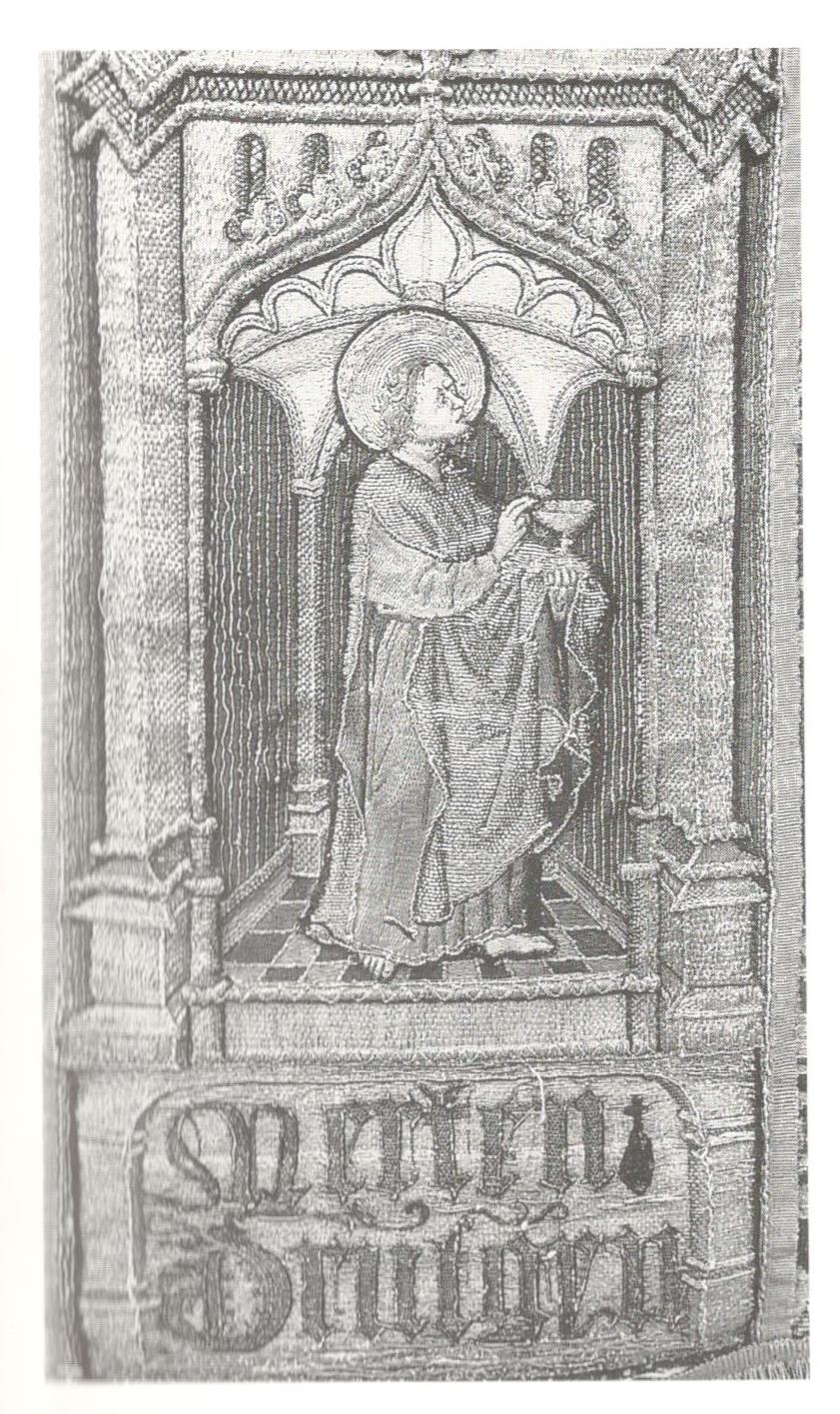

The chasuble that sports the identical twin of Saint John in the Frankfurter Domschatz is part of a set consisting of one chasuble and two dalmatics. The cope, which would have made the set complete, is missing. Although the set is now housed in Frankfurt, it probably originated in a church in 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands. Below the orphrey with Saint John are the names 'Merten' and 'Drutgen' stitched. The beneficiaries of this set of vestments. Merchant and member of the city council, Merten Moench/Maarten Monicx and his wife Drutgin von der Groeven. Merten was born in 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, but his wife was from Cologne. She died in AD 1451 and he died in AD 1466. Maarten likely donated the vestment set in 1460 to a church in his hometown of 's-Hertogenbosch.

The chasuble is made of red velvet shot with goldthreads. It is one of these famous red velvets made in Florence, Italy sporting pomegranates. The orphreys on the front show: Paul, Peter and Mary Magdalene. The ones on the back show: God, Mary with child, John the Baptist and our Saint John. All of them sport high-quality or nue figures set in a golden architectural background with blue silk stitches with a similar tiled floor stitched in yellow, red and green silks. Whilst the figures look very Dutch, the backgrounds don't. The blue vaguely reminds of the 'Kölner Borte'. These were mass-produced woven orphreys that sometimes showed additional stitching for the details.

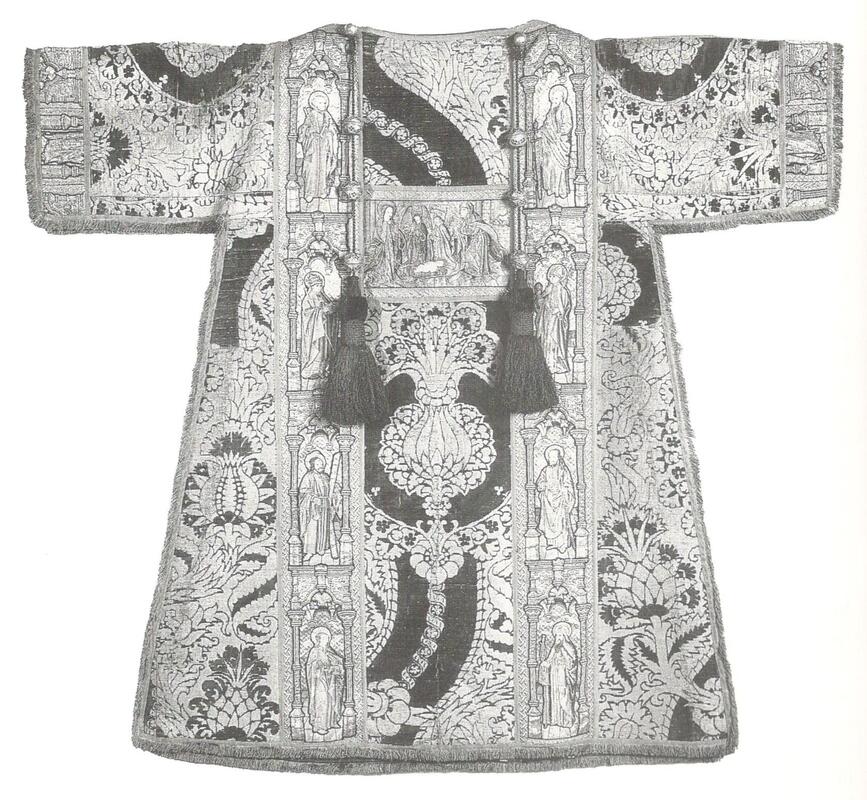

The two dalmatics are made of the same red velvet. But this time the orphreys are 'right'. High quality or nue figures sitting in a proper golden background so typical of the Dutch style.

What is going on here? We know from the historical records that the vestments were extensively restored in 1842/43 by the painter Edward Steinle and a parament maker and his two daughters from Cologne, with the help of another painter and conservator, Johann Anton Ramboux. It took them about a year to clean the vestments up and make them presentable again. They were paid 100 Taler for their work. That's about €4860 in today's money according to Google. I really hope they had additional income ... Anyway, although the vestments were extensively restored, the difference in backgrounds between the chasuble and the dalmatics is a medieval one and not the result of these restorations.

How does the single orphrey from Dommuseum Fulda fit into this story? As this orphrey has the same figure and background as the ones on the chasuble from Frankfurt, he is very likely part of the original set of vestments donated to the church in 's-Hertogenbosch. Beneath the original orphrey, another coat of arms is displayed. On the chasuble, the names of the beneficiaries are stitched beneath the orphrey of Saint John.

Looking closely at the figures on the chasuble, we see that they either look to the left or to the right. Furthermore, the orphreys are significantly wider than those on the dalmatics. This is a typical convention. Orphreys on a chasuble, but also on a cope, are wider than those on a dalmatic. The orphreys on a cope sit opposite each other at the front when the cope is being worn. The orphrey figures face each other: one faces to the right and the other faces to the left. This means that both the orphreys on the chasuble and the single orphrey from the Dommuseum Fulda were originally made for a cope. God would have sat opposite of Mary with child, Peter and Paul, Mary Magdalene and Saint John and John the Baptist is missing his partner in crime.

Now, this can mean several things:

1) Merten and his family were merchants with connections to the (Southern) Netherlands. They knew this type of goldwork embroidery well and valued it. Getting it from the Netherlands instead of opting for locally produced 'Kölner Borte' shows that these vestments were quite valuable and perfect to show off. 2) They were able to lay their hands on a number of loose orphreys and figures from the Netherlands and velvet from Italy. 3) These orphreys, figures and precious velvet were turned into vestments in Cologne by local craftsmen. These saw the 'complete' Dutch orphreys and worked orphrey backgrounds in a similar style, but with local influences to go with the loose Dutch figures. Names and coats of arms were added to make clear who bestowed these riches onto the church. 4) Orphreys intended to go onto a cope were instead applied to a chasuble. Or were they moved from a cope to the chasuble between AD 1460 and AD 1842/43? Does Saint John from the Dommuseum Fulda come from the original missing cope or copes? Or were so many figures bought at the same time and turned into 'Cologne-style' orphreys by the same workshop and then spread within Germany? Is the orphrey of Saint John in the Dommuseum Fulda the only remnant of a whole different set of vestments made in Cologne? One way of finding out is by identifying the coat of arms on the loose Saint John orphrey. I intend to write to both museums to ask if they know more. So exciting! I will keep you posted. Literature Fircks, Juliane von (2010): Serienproduktion im Medium mittelalterlicher Stickerei - Holzschnitte als Vorlagenmaterial für eine Gruppe mittelrheinischer Kaselkreuze des 15. Jahrhunderts. In: Uta-Christiane Bergemann, Annemarie Stauffer (Eds.): Reiche Bilder. Aspekte zur Produktion und Funktion von Stickereien im Spätmittelalter. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 65–82. Stolleis, K., 1992. Der Frankfurter Domschatz Band I Die Paramente. Kramer, Frankfurt.

10 Comments

NancyB

7/9/2020 12:09:08

This mystery really is exciting, and I'm sure there's a book to be written about all this.

Reply

7/9/2020 18:14:08

I think I am going to contact Dan Brown for that part :).

Reply

Margaret Morgan

7/9/2020 14:33:19

Really interesting - I am looking forward to more results from your research.

Reply

7/9/2020 18:14:56

Thank you Margaret! I really hope the museums have more information and are willing to share :).

Reply

Christine V

8/9/2020 17:03:09

What a fine eye you have to notice these separated pieces Dr Grimm! It’s very exciting to read how you’re able to understand the uses and family history of these medieval works and group them together for the first time in ages. I’ll be interested to learn what additional information you obtain from the museums and how you interpret more of their history. Please keep us updated on the contract you grant Dan Brown ;)!

Reply

8/9/2020 18:22:37

Dear Christine,

Reply

9/9/2020 19:54:00

I really hope so Rachel! Amd otherwise they can put my letter to the stack they already have :).

Reply

Darcy Walker

9/9/2020 18:01:32

What great research and understanding of the

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed