|

Over the years, I have come across the names of hundreds of medieval embroiderers. A couple of names can often be found in papers on medieval embroidered textiles. Sometimes, a whole list is provided, for instance, of those people who worked on embroidered textiles for Duke Philip the Good in AD 1425. Or we have a nice paper on a particular embroiderer and his conduct. Analysing the development of the embroidery trade through surviving guild regulations is also a good source of names. Each of these instances is anecdotal. As far as I know, there isn't a central database which lists the personal details of medieval embroiderers from Europe. That can be easily changed! From now on, I will maintain an Excel list. The list will be accessible through this blog (easily found through the blog index under 'medieval embroiderers`). Although I have gathered an impressive 294 names, my list is far from complete. Please contact me if you want to see names added to the list. My cut-off point is AD 1550-ish. Curious if someone with your (sur) name is on the list? Let's find out! So far, I have been able to find embroiderers from as early as the 9th century and for each subsequent century right up to the mid-16th century, which is where my cut-off point is. They come from sources in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden. The further back in time we go, the less information we have. As you probably feared, most of the embroiderers who made it into the written record were male. Of only 45 embroiderers, I can be certain they worked with gold threads. Interestingly, the male:female ratio still holds. This does not mean that women did not embroider professionally. It does mean that they were not as often in a position that needed for their names to be written down as embroidering men were. As soon as we split the available data into the appropriate centuries, a slightly different picture emerges. Although based on very small numbers, the data probably hints at a change in society. Professional embroidery was probably done predominantly by women in the early Middle Ages before men entered the field in the high Middle Ages. However, the data for the early Middle Ages comes predominantly from England. Thus, what we see might result from geographical differences and not applicable to all of medieval Europe.

Those who would like to investigate and/or play with the raw data can download my Excel file by clicking on the above link. Enjoy!

Please note: I am off to attend the International Istanbul-Büyükcekmece Culture and Art Festival tomorrow. After that, I'll take my summer break to work on the program for the rest of the year. Blogging will resume on the 2nd of September!

1 Comment

When I reviewed the 'Art of Gold Embroidery' a few weeks ago, the book's biggest drawback is that it is mainly written in Uzbek and Russian, languages most of us are unfamiliar with. It also seems to be impossible to get hold of. Several people asked me if 'The art of gold embroidery in Uzbekistan' by Suzanne Pennell would be a good alternative. As this was also the primary source used by Dr Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood in her chapter on Uzbek gold embroidery in the 'Encyclopedia of Embroidery from Central Asia, the Iranian Plateau and the Indian Subcontinent', I decided to order a copy and review it for you. Suzanne Pennell wrote the book almost 25 years ago. It is her master's thesis submitted to the James Cook University in Australia. Various online bookstores offer the book as 'print on demand'. This means that the book looks like you have printed it on your home office printer. The many pictures in the book are of sufficient quality to accompany the text. However, you would be disappointed if you hoped to drool over detailed images of the beautiful goldwork embroidery. Also, keep in mind that this is a MA thesis. It was written by someone who relied entirely on translators to do her field research in Uzbekistan, as she could not speak Uzbek or Russian. That being said, it is the only book available in English which summarises the extant Russian literature on the topic. The book starts with a short introduction and the research methods employed. Pennell interviewed the embroidery master Bakshillo Jumeyev (writer of the 'Art of Gold Embroidery', a mother and daughter preparing a trousseau, visited museums in Tashkent and Bukhara and ploughed through the literature. The first chapter gives a broad overview of the history of the area of Uzbekistan and the archaeological and historical evidence for gold embroidery. As noted before, the evidence is scant, primary literature resources are absent, and references in classical Greek literature are not critically reviewed. This would be an excellent research topic for an embroiderer fluent in Uzbek, Russian and preferably Chinese. The second chapter I liked best. It talks about the materials and tools used and the organisation of the embroidery guild. To me, this is an ethnographical study that compliments my research on medieval goldwork embroiderers. It fleshes out the scant information I have and paints a picture of how the lives of medieval gold embroiderers might have been. It also makes you realise how little we know. For instance, every diaper pattern likely had a name. It makes communication within the embroidery workshop and between the workshop and the client a lot easier when techniques and textures have names.

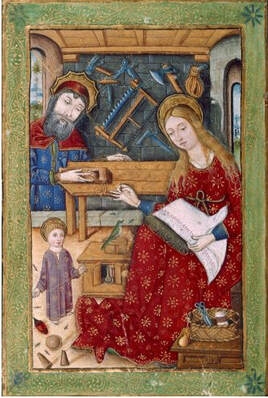

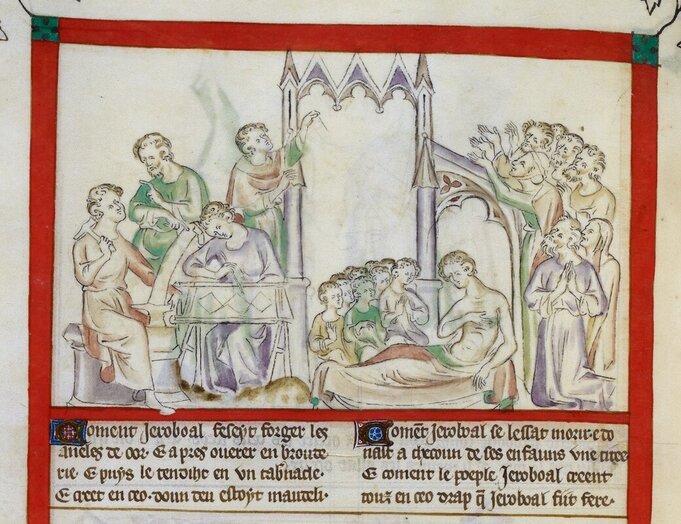

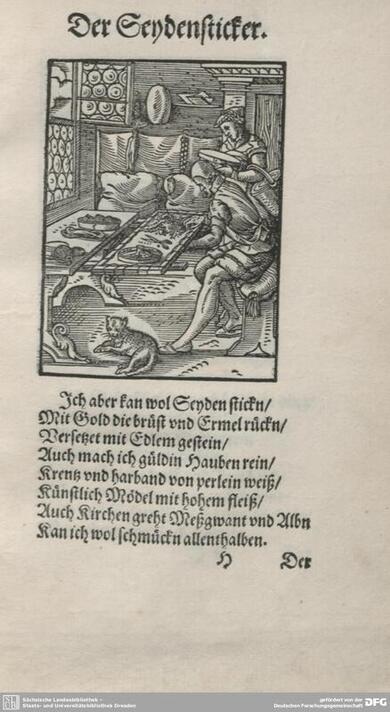

I found the rest of the book also extremely interesting! Pennell aimed to document and explain the changes goldwork embroidery in Uzbekistan had undergone when regimes changed from Emir to Russian Tsar to Communist Russia to independence in 1991. A whole chapter is dedicated to detailing the practice at the last courts of the emirs. Opulence and self-indulgence led to a Golden Age for Bukhara's gold embroidery. At first, not much changed when Tsarist Russia colonised the area. However, everything changed after the October Revolution in 1917, especially as Bolshevik ideology required women to emancipate and join the workforce. Gold embroidery changed from a predominantly male occupation into a female occupation under state control. After Independence in 1991, the Uzbek government actively promotes goldwork embroidery to forge a new national identity. Reading Pennell's MA thesis, I better understood why the Uzbek government pours so many resources into organising a biannual International Gold Embroidery Festival. Such festivals hail back to the days of the emirs when fairs like these were held several times a year to display the products and skills of all the master embroiderers and their workshops. And remember the gold embroidered coat every participant got? That's an ancient custom, too. Gifting 'robes of honour' to important guests was quite the norm. All in all, I really liked the book, especially because I can use its contents to help me understand the pictures and texts in the 'Art of Gold Embroidery'. Getting hold of the original Russian literature in the West would be very time-consuming. This is a much cheaper alternative and will do for most of us. This book is for you when you are interested in national dress and ethnography! You can order your print-on-demand or second-hand copy through the AbeBooks website. As I was studying a Portuguese book on medieval embroidery, I came across an article by José Alberto Seabra Carvalho on the craft of embroidery in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period. Although he acknowledged that some embroidery was undertaken by the women in noble households and by nuns in convents, he also came to the conclusion, by studying the surviving pieces and combining them with the historical records, that those were made by men in commercially run workshops. Their quality is simply too high. It requires many years of training before one is able to make a living from making orphreys. At the same time, he briefly investigates this ideal of the 'pious woman'. As long as her hands were busy doing needlework, she could not daydream and get into trouble. In addition, her handy work could contribute a bit to the household. These opinions are not his but come from contemporary sources. And here we have precisely this duality: needlework itself is not much valued as it is done by women to keep them from having a wandering mind. While at the same time, commercially produced goldwork embroidery requires many years of training and is thus the domain of men. The duality and stigma embroidery 'enjoys' today is thus an old one. Art versus craft. And only for women. Let's explore what that looks like in medieval and early modern images! Female embroiderers are depicted in two different ways: stitching in hand or sitting behind a slate frame resting on trestles. Usually, it is not ordinary women that are depicted embroidering. Especially not in the earlier periods. It is either Mary employing a needle or a queen/noblewoman stitching. Stitching in hand requires very little in terms of professional tools. Mary on the left has a simple basket filled with scissors and a bobbin with thread. This is in strong contrast to Joseph's array of professional carpenter tools hanging on the wall. By the way: I don't think St Francis would approve of Jesus tying a rope to a bird :). Contrary, Mary on the right, is shown in a much more professional setting. She uses a large slate frame and a pair of trestles. The spool she is holding might be wound with gold thread. It looks like she is using her slate frame and trestles set-up as a kind of working table with balls of yarn laying on top. Some people argue that this shows Mary making a tapestry instead of an embroidery. However, I think she is in the process of couching down a gold thread on top of red and green silk embroidery. In both images, combining embroidery with childcare seems not to be a problem. Maybe that's why the child is harassing the bird? Male embroiderers, on the other hand, are depicted in one way only. As professionals. No cosy stitching whilst watching a child. Maybe medieval and early modern men were just not prone to 'daydreaming and getting into trouble'?

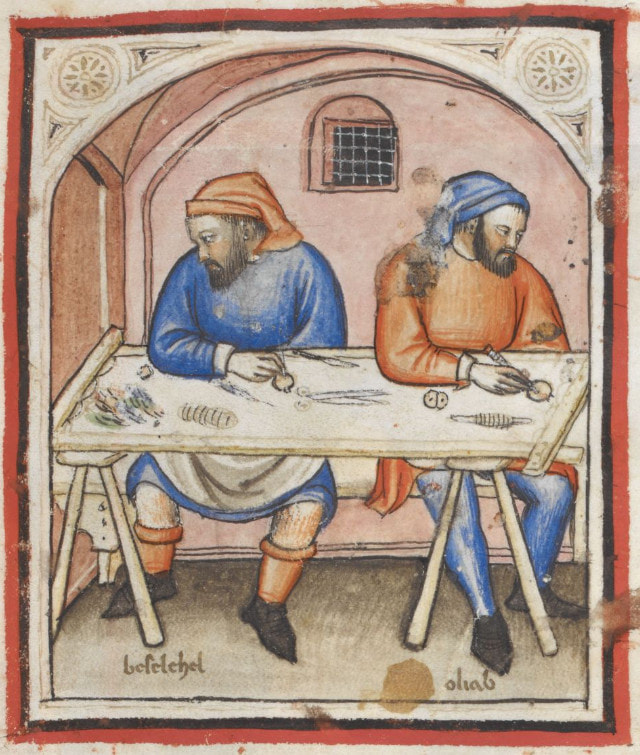

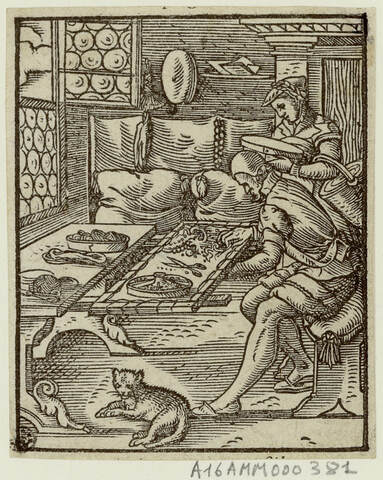

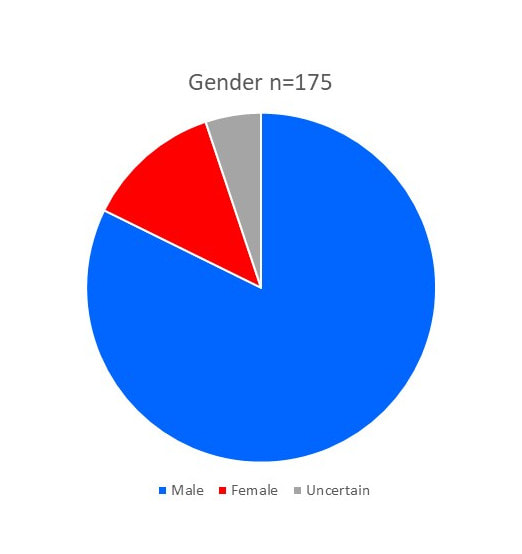

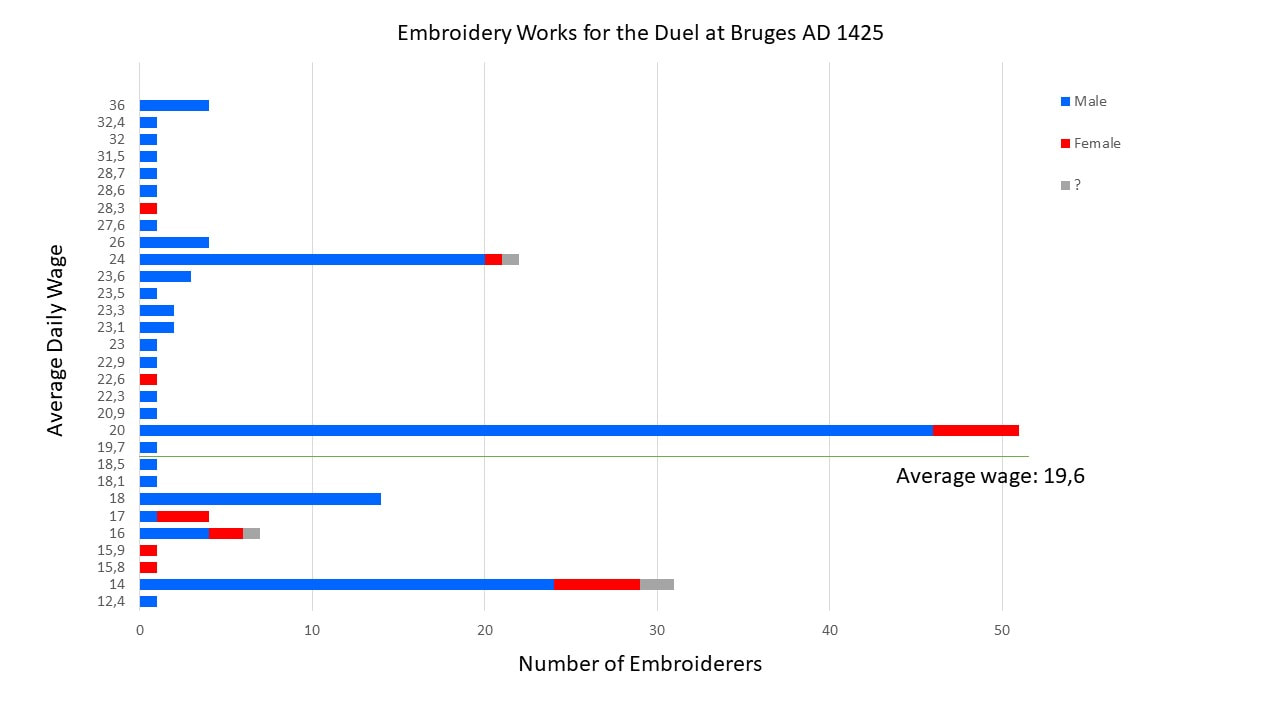

The above illustrations show men sitting behind slate frames in the typical posture of an embroiderer. One hand above the frame and one hand below to speed up the process. And I love the non-ergonomic posture of the man on the right. At least none of the above men can be told off for crossing their legs :). By the way, I think we also see very realistic depictions of how these professional workshops were set up back in the day. The men on the left are probably working outside under a portico. Maximal use of daylight, but a bit sheltered from the weather conditions. The man on the right has the luxury of window glass. But he still needs to sit right in front of them and even needs to open the top window for clear, unfiltered daylight. The stereotypes depicted in the above images, some over 600 years old, seem to persist today. When I am demonstrating professional goldwork embroidery at my local open-air museum I get many stereotypical reactions. Many women equate what I am doing with cross-stitch embroidery. And when they hear that this is not my hobby, but my profession, I get 'the look'. It is not a kind look :). Some even react very irritated. How can a woman, who has gone successfully through university, want to stitch for a living?! How on earth did I sink so low? Very few women admit that they themselves stitch. And the ones that do, get younger from year to year. So, there is hope! Many men, on the other hand, have a very different reaction. They univocally acknowledge that what I am doing is very different from the needlework their mums and wives did or do. They are interested in my tools and the mechanics of it all. Some remark that this is 'typical' women's work. When I then explain that this was a male profession for hundreds of years, I have their full attention. Some even ask if I personally know male embroiderers (Gary Parr, you are getting famous here in Bavaria!). A few are so intrigued, they revisit the museum and seek me out to see how the work has progressed. And as they can precisely point out what I had accomplished last time, it is clearly about the embroidery and not about me :). I really hope that some people who see me stitch in the museum pick up a needle. Regardless of their reaction. Embroidery is fun! The ancient forms should be studied and revived. The professionalism of the makers should be acknowledged and valued. I hope you liked this blog post. Maybe it can contribute a bit of 'fact' to the craft versus art debate. Knowing that we are repeating the medieval and early modern idea of the 'ideal woman' when we see embroidery solely as a craft (in the modern sense), might make people think twice before they argue their case. The above images are not the only ones I have collected over the years. My valued Journeyman and Master Patrons will have access to a Padlet with 10 additional images. Literature Seabra Carvalho, J.A., 1993. O Ofício. In: T. Alarcão & J. A. Seabra Carvalho (eds), Imagens em paramentos bordados seculos XIV a XVI, Instituto Portugues Museus, p. 16-21. Seldom do we have a chance to meet the people who created the medieval embroideries. Especially written sources containing the names of female embroiderers are rare as hen's teeth. Imagine my delight when I found an older Belgian publication that contains precisely that! It is a list of 175 (!) people who were drawn in from all over the place to help embroider equipment, clothing and tents for a duel between Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and Humphrey Duke of Gloucester. The original documents preserved do not only tell us something about the embroiderers and other craftspeople involved, we also have a list of the embroidered items. Let's explore! Why did these two men think it a good idea to fight till death? It was about a woman: Jacqueline Countess of Hainaut. She interfered, with her second husband Humphrey, in the power politics of Philip the Good by trying to claim her rights in Hainaut. In essence, it was a family feud as most of these people were closely related to each other. In order to have the most splendid kit to try to kill Humphrey, Philip ordered his man Andre de Thoulongeon to ride to Paris in haste to collect master craftsmen in the art of weaponry, painting and embroidery. Andre contacted Thomassin de Froidmont, Philip's weaponry master, Thierry du Chastel, who later surfaces in the historical sources as Philip's head embroiderer and the painter Hans de Constance (his name suggests he came from Konstanz in Southern Germany). Painter Hans came to Bruges and worked for 70 days on the embroidery designs. Simon de Brilles, an embroiderer of Philip, was asked to take care of the masters that came from Paris and to direct the embroiderers that worked on repairing the embroidery on the weapons and Philip's tent. The first embroiderers arrived at Bruges on the 26th of March 1425. They worked in the ducal palace. Over the next weeks, more and more embroiderers arrived. They came from Bruges, Ghent, Lille, Brussels, Mechlin, Antwerp, Tournai and many other places. All in all, 175 people of which 22 were certainly women (I wasn't sure about 9 names if they were male or female). This underlines the general impression I have so far gotten from the historical documents that significantly more men worked as professional embroiderers than did women. Some people stayed the whole 70 days and others came for only a couple of days. They finally completed the task on the 21st of June. What did 175 embroiderers produce between the 26th of March and the 21st of June 1425? They made seven horse trappers made of velvet and embroidered with the coat of arms of Philip or his counties, his motto and the cross of St Andrew. As far as I know, the only surviving medieval embroidered horse trapper is held at Musee Cluny in Paris (Cl. 20367 a-g). They also made tabards, those heavily decorated tunics that were worn over chainmail or harness. Furthermore, banners and a tent needed to be decorated with embroidery. The Belgian authors think this not to be very much ... Why then did some embroiderers have to work through the night to get it finished in time?! In the end, it was all for nought. Philips and Humphrey decided that trying to kill each other wasn't the best way to solve the conflict. Diplomacy did. On the 23rd of Mai 1425, the duel was called off. Interestingly, the embroidery works continued until the 21st of June. The, no doubt, splendid embroideries were transported to Lille on the 9th of September and kept there for safekeeping. Maybe they were used for the tournament in which Philip the Good and John of Lancaster both appeared in 1427. There is a written source that confirms that the tent made for the duel could still be admired in Lille in 1460. Unfortunately, none of the embroideries seems to have survived till the present day. The list in which the embroiderers are listed shows some interesting details. Foremost, we learn how much each of them was paid. Some got the same payment for each day they worked, others got different wages on different days. Was this because costs spiralled out of control? Or were different tasks paid differently? I tend to think it is the latter. You were presumably assigned to a certain task and when that task was completed you got assigned the next one when you decided to stay on. Those who practice goldwork embroidery probably know that some techniques and designs require more skill than others. Related to this is the payment of the female embroiderers. The Belgian authors state that the work of women was rewarded less. This conclusion is probably cut too short. Lievin van Bustail, Lyzebette Peytins and Yoncie Hevre all earn quite a bit above the average wage of 19,6 gr. It is true, however, that the top earners are men and that 14 of the 22 women earned wages below the average. Four women came with their husbands: Ernoul and Marguerite de Wesemale both became the same wage of 20 gr., the same is true for Alard and Katherine du Dam. Jaquet d'Utrecht earns 20 gr, his wife (not named) earns 16 gr. and his boy (not named) 14 gr. Pietre de Hond only earns 18 gr. and his wife (not named) earns even less at 14 gr. Young boys either earned 14 gr. or 11 gr. This seems only fair as these were probably still training with their masters (maybe their fathers?) and were thus not that skilled. I am therefore thinking that embroiderers were primarily paid according to skill and not according to their gender. For those of you who like to play with the raw data below is the Excel list for you to download. If you can help sex any of the names now a '?' or if you see a mistake, please let me know!

Literature

Duverger, J., Versyp, J., 1955. Schilders en borduurwerkers aan de arbeid voor een vorstenduel te Brugge in 1425. Artes Textiles II, 3–17. Some of you will know that I don't have a tv. Instead, I watch interesting documentaries (and highly necessary series like 'The Great British Bake Off`) directly on my laptop. One of my favourite channels is 'Arte' a French-German co-production. During this weekend's browse, I found a five-part series on the artisan production of fabric in Asia. Very beautiful and informative! The one on India zooms in on an embroidery atelier in Mumbai directed by the Italian professional embroiderer Maximiliano Modesti. He employs 600 embroiderers. All male, 98% muslim. Women do embroider, but not in a professional setting. This made me wonder how things were done in the 15th and 16th centuries in the Low Countries? After all, my favourite style of goldwork embroidery that I use as a basis for my artwork was made during this time. Would master embroiderer Jacob van Malborch have employed me if I had also lived in Utrecht in the first quarter of the 16th century? Someone who has done extensive research during the '80s and '90s into the organisation of professional embroiderers during the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times in the Low Countries is Prof. Dr. Saskia de Bodt. She extended and corrected the earlier attempts of Dr. Beatrice Jansen executed some 40 years earlier. In more recent years, art historian Dr. Marike van Roon researched the Dutch embroidery ateliers active between 1830-1965 extensively. As far as I know, more recent research into the role and organisation of medieval embroiderers is not available for the Low Countries. Note: It seems that the above-named scholars started their careers researching embroidery, but soon gave up in favour of more 'real' art history like 19th-century paintings or ceramics. Even in research, embroidery seems to have an image problem ... After going through many written sources such as the financial records of churches and towns, baptism records, marriage registers and death records from the 15th- 17th century located in the Northern Netherlands, Saskia de Bodt concludes that the professional embroiderer was a man. Only the men, like Jacob van Malborch and many others, are named. If a woman does show up in the records it is not under her own name but only as huysvrou van (housewife of) followed by the name of the master embroiderer. However, women were not explicitly excluded from the guild either. On the contrary. When the embroiderers of Utrecht formed their own guild in 1610, the guild ordinance speaks of meestersschen (female masters). The guild of embroiderers in Leeuwarden probably only consisted of men as the ordinance only mentions meesters and inwoonderssonen (masters and sons of poorters). But in Dordrecht, the embroiderers split from the St. Luke guild in 1487 as a result of a feud between the women ...

So would master Jacob van Malborch have taken me on as an apprentice? Possibly. Would someone have written down my name? Certainly not in the Low Countries. Female embroiderers are known from the written sources in other European countries. So I could have learned the ropes with master Jacob and then, after fretting over not making it into the written record, emigrate to Cologne or over the seas to England. But that's stuff for a further blog post. Sources: Bodt, S.F.M. de, 1991. Borduurwerkers aan het werk voor de Utrechtse kapittel- en parochiekerken 1500-1580, Oud Holland 105, pp. 1-31. Bodt, S.F.M. de, 1987. De professionele borduurwerkers. In: S.F.M. de Bodt, M.L. Caron et al, Schilderen met gouddraad en zijde, Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht. Jansen, B., 1948. Laat Gotisch borduurwerk in Nederland, Boucher. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||||||||

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed