|

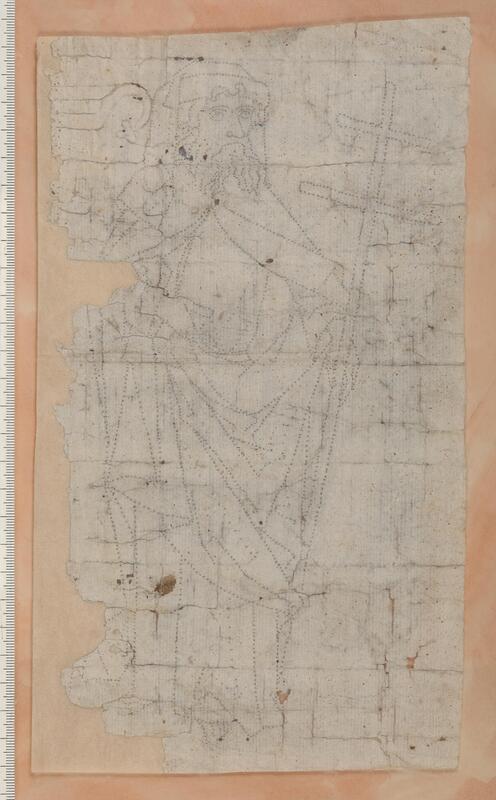

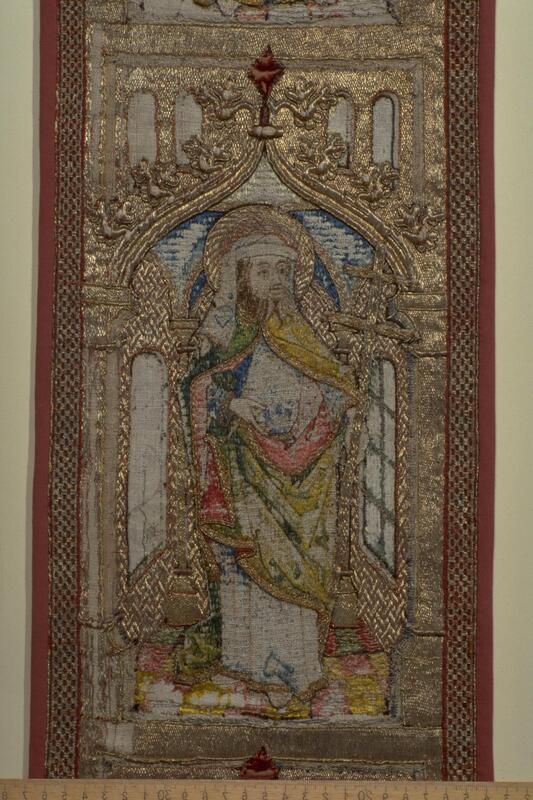

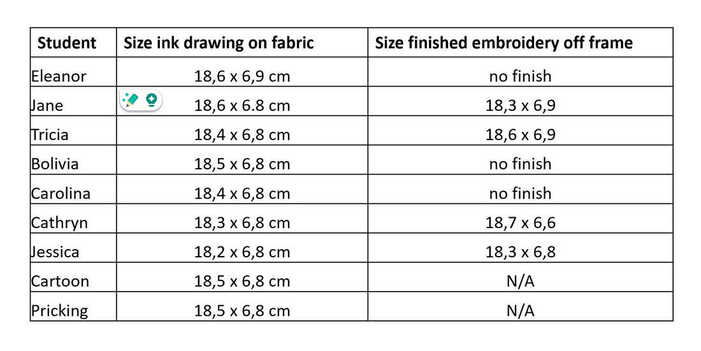

How much does the size of the finished embroidery differ from the cartoon and the pricking it was made with? Any idea? Me neither. But I read a reference by Evelin Wetter a couple of years ago that tried to link a rare surviving medieval pricking to a surviving embroidery. However, the measurements of both were slightly different. So how different are cartoons, prickings and the resulting embroideries? Time for an experiment and in comes Elisabeth. The original reference mentions the find of a pricking being reused as the backing for a finished embroidered antependium (to stiffen it) found in Hillersjö, Sweden. The pricking shows Philip the Apostle. The pricking is identical to an embroidered Philip the Apostle on a cope orphrey from Linköping Cathedral in Sweden. According to the reference, "compared to the pricking, the embroidery appears to have shrunk by a few millimeters". Unfortunately, I wasn't able to find precise measurements of either the pricking or the finished embroideries on the cope orphrey. From the ruler depicted in the picture of the pricking, the pricked figure must be about 24,75 cm. From the ruler in the picture with the orphrey of Philip the Apostle, the embroidered figure must be about 23.7 cm high (excluding the halo, just as in the pricking). If we compare this with the height of the pricked figure (24.75 cm) we have a difference of about 10.5 millimeters (slightly over a cm!). This would more or less correspond with the original reference's mention of 'a few millimeters'. It looks a little high to me, to be honest. And when my deducted measurements are correct, I doubt pricking and embroidery are identical. In the original reference, the difference between the size of the pricking and that of the embroidery is explained by the transfer process described by Cennini in his Libro dell'Arte of c. AD 1370. In it, a near-dry sponge is used to slightly wet the free-hand drawing to add shading. Now, there's several things mixed up here. Cennini described the embroidery design transfer process for a design drawn onto the embroidery process free-hand. The pricking of Philip the Apostle and the resulting embroidery stem from a very different process. No free-hand drawing. And as we can see in the damaged parts of the finished embroidery: it is a line drawing with no shading. The embroidery linen can thus not have shrunk, as the original reference of Evelin Wetter suggests, due to the application of a little water in the wetting process to add shading. If art historians make assumptions like the one by Evelin Wetter, you might think that they have conducted an experiment with modern embroiderers, don't you? But, nope. So, I decided to use my teaching at the Alpine Experience in 2022 as such an experiment. Just having my own measurements would be a bit skimpy on the data side of things. And I am very grateful that three students of that class finished their embroideries and that I was able to measure their embroideries during 2023's class. Here are the results: As you can see from the above table, the cartoon (design drawing) and the resulting pricking do not differ in their measurements. Everyone used the same pricking. The resulting design drawing on the embroidery fabric made with pounce and ink already differs slightly: up to 3 millimeters in height and 1 millimetre in width. Some are larger, others are smaller than the pricking. The finished embroidery differs up to 2 mm in height and 2 mm in width. Again, some are larger and some are smaller. This is the comparison we are after as this compares the pricking with the finished embroidery just as for Philip the Apostle.

My conclusion thus is that small differences in measurements between a pricking and the resulting embroidery are normal. These differences can go either way: larger or smaller. They are the result of the maker going through several transfer steps: pounce dots from the pricking, turned into an inked line drawing, turned into an embroidery. The absolute difference in millimetres thus directly relates to the size of the brush for the inking and the size of the embroidery materials. Particularly the width of the gold thread at the turns on the design line probably attributes the most to the size differences seen. A huge thank you to my students who were brave enough to tackle Elisabeth! You have provided me, and the wider research community, with tangible data on this particular topic. Literature Nisbeth, Åke; Estham, Inger (Eds.) (2001): Linköpings domkyrka. Inredning och inventarier. Linköping: Linköping Domkyrka. Wetter, Evelin (2012): Mittelalterliche Textilien III. Stickerei bis um 1500 und figürlich gewebte Borten. Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung.

4 Comments

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed