|

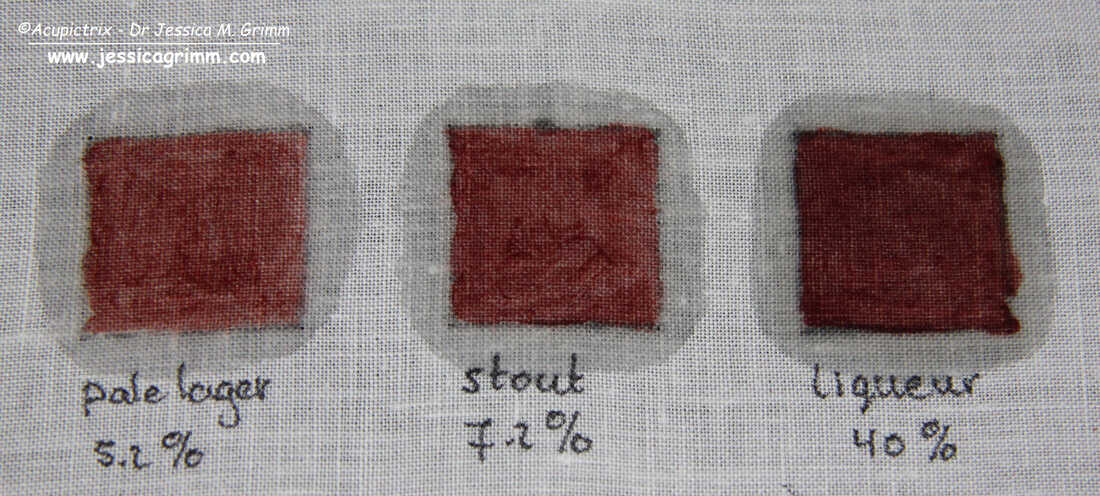

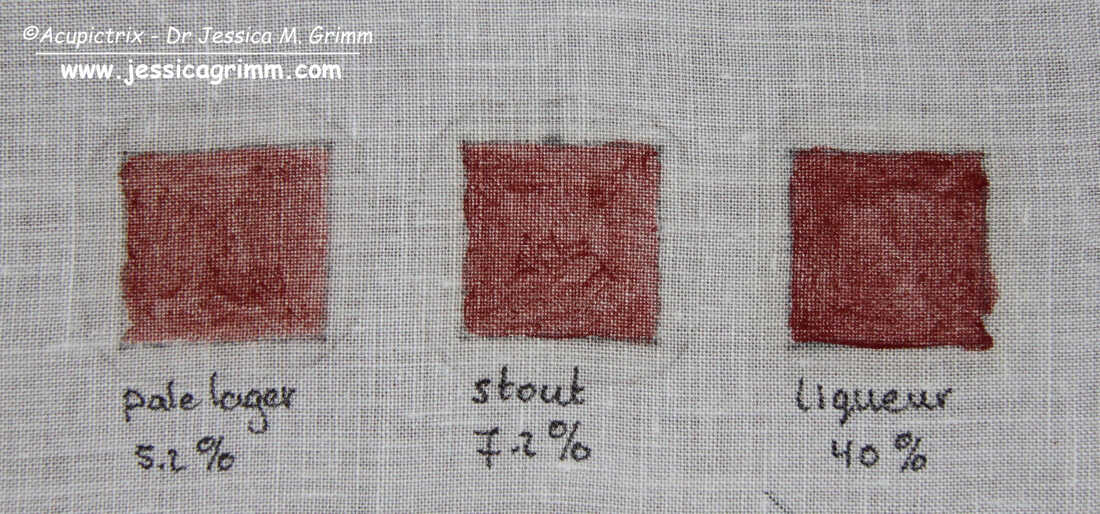

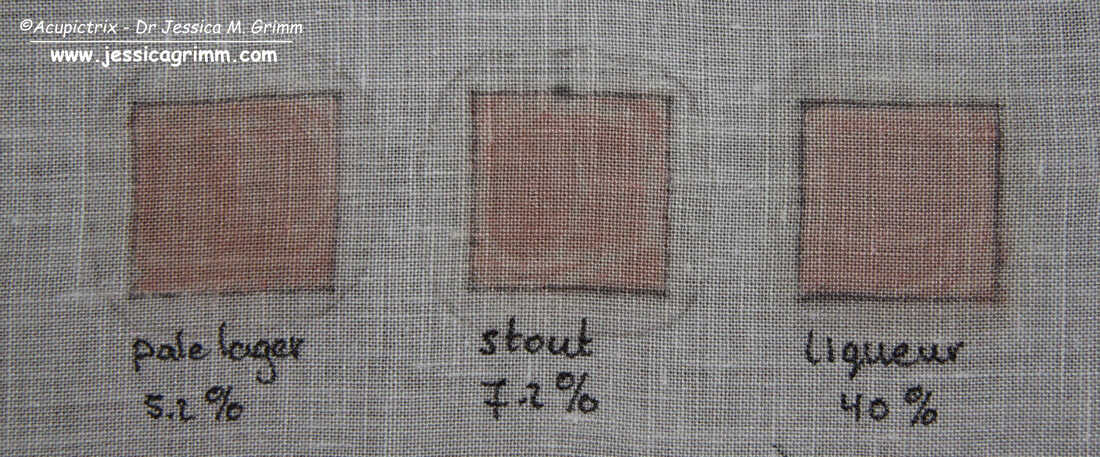

Asking for beer at 9:30h in the morning raised a few eyebrows next door at the abbey. Assuring Friar Markus that it was needed for an embroidery experiment did not improve things much. But it was the truth. What had happened? During my talk for MEDATS, I asked the audience for help with the madder conundrum. Whilst oil will do the trick, the greasy halo is very unsightly. Afterwards, I was contacted by Deborah Fox, who had done some dyeing experiments herself and she suggested alcohol. Ale was omnipresent in the Middle Ages as most water was too polluted to drink. I had always dismissed this option as I had a feeling that the hydrophobic madder would still think beer was too watery. However, I live next door to Ettal Abbey and they have been brewing and making liqueur for hundreds of years. Friar Markus was kind enough to sponsor the experiment with some homemade booze. For the experiment, I dissolved (or tried to dissolve) an 8th of a teaspoon of madder powder into a teaspoon of pale lager (5.2%), a stout (7.2%) and liqueur (40%). I drew three 3x3 cm rectangles with iron gall ink on my normal white embroidery linen. As I had expected, the pale lager and the stout were too watery for the madder's taste. It would not dissolve at all. But it did dissolve beautifully in the liqueur. And the smell was really nice too. Very herbal. I let the samples dry for a couple of hours. All did produce a bit of a halo but nothing too bad, I think. When the samples were completely dry, I brushed off the excess madder powder. Oh, dear! We get a very similar result to my experiments with only water. The madder just does not go into the linen enough as it does with the oil. And we still have a halo. This probably means that booze isn't the complete solution either. Maybe several substances were mixed with the madder powder to get the right result? More experiments are needed!

17 Comments

When you start to analyse medieval goldwork in detail, you'll find all sorts of things that are not practised in modern goldwork embroidery. One of these is the use of madder (Rubia tinctoria), a red pigment to colour the embroidery linen in those areas that get covered with goldthreads. How widespread the use of this pigment was is difficult to say. Its use can only be observed when an embroidery is damaged. However, as it is not present on each damaged embroidery the use of madder was not a necessity. As far as I know, the madder was first chemically identified on pieces from the Schnütgen Museum. The reason given by Sporbeck for its use is that the inferior quality of the membrane gold used in Germany needed this reddish base to enhance its shininess. She falsely concludes that the use of madder is probably unique to embroideries made in Cologne. However, the madder can be found under Dutch embroideries also. It was probably simply used to prevent the white linen to shine through the golden backgrounds stitched with geometric diaper patterns. Especially when patterns with larger intervals between the individual couching stitches were used, the goldthreads may gape and reveal the white linen. The colour red enhances the shine of the gold and tricks our eyes into believing that the background is whole and smooth. But how was the madder applied?

As the madder is only applied on those areas of the embroidery linen that later get covered with goldthread, the medieval embroiderers did not simply use madder dyed embroidery linen. I think this has to do with the silk embroidery. The red background colour might interfere with the very light silk used in the faces. In order to be able to only use the red colour in certain areas the person who drew or printed the design onto the embroidery linen must have used a paint-like substance. What binding agent was used to turn madder powder into paint?

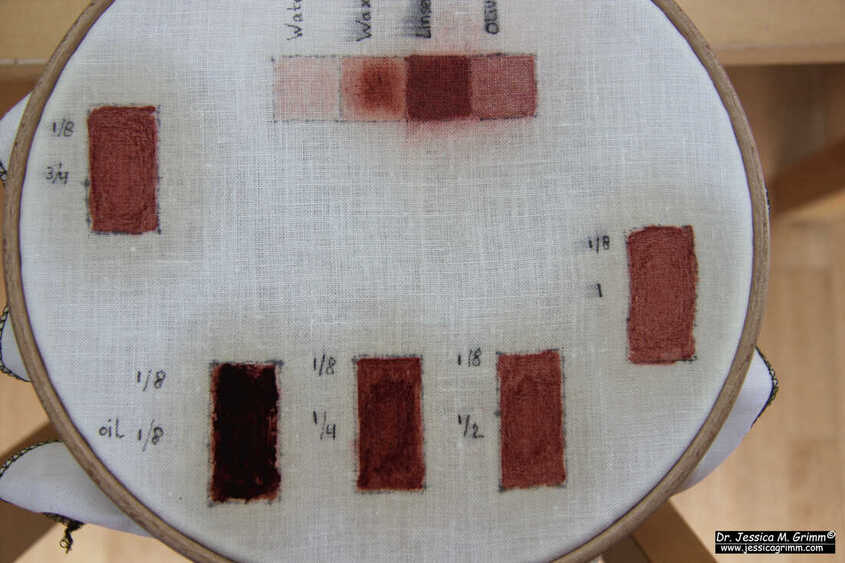

In the above FlossTube with the Acipictrix video, you'll see me experimenting with different binding agents. Whilst madder powder is hydrophobe and does not dissolve well in water, you can actually stain your embroidery linen just enough to get rid of the stark white. The binding agent that has worked best so far is linseed oil. You'll need 1/8 teaspoon of madder powder and 1 teaspoon of linseed oil to get a paint-like substance that adheres well to the linen without excess madder powder sitting loosely on top of the fabric. This shows that the pigment is very economical in its use. Both madder and linseed were common, inexpensive and local products.

The one thing that bugs me about the use of oil as the binding agent is that it seeps into the embroidery linen. This was apparently a common problem for painters too. In the reconstruction of the Nachtwacht by Rembrandt, the modern painters had the same problem. The canvas kept sucking up the linseed oil paints. They remedy this problem the same way the people in Rembrandt's workshop would have done: by drenching the canvas in more linseed oil. However, this would not have been necessary for the medieval goldwork embroideries. They were completely covered with embroidery and the 'halos' of seeped oil would simply not be visible.

When I had found my preferred recipe for the madder paint and applied it to my embroidery linen, I was amazed that you can easily stitch on it. It does not feel oily and it does not seem to interfere with either your silken couching thread or with the goldthreads. I have no idea how long the 'halo' stays visible. It is difficult to see if there is a halo on the damaged goldwork embroideries (explore: ABM t2007, ABM t2107a, ABM t2121b, ABM t2147, ABM t2149, ABM t2158 & OKM t156a). However, in the picture above, you do see some staining on the back of ABM t2107f. This might be the result of the oil used as a binding agent.

Just a word of caution: If you would like to experiment with making your own madder paint with linseed oil, be careful. Linseed oil generates heat when it dries. Under the right circumstances, it can combust and cause a fire. Always let fabrics drenched in linseed oil dry completely before you throw them in the bin. Literature Leeflang, M., Schooten, K. van (Eds.), 2015. Middeleeuwse Borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden. WBOOKS, Zwolle. Sporbeck, G., 2001. Die liturgischen Gewänder 11. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Sammlungen des Museum Schnütgen 4. Museum Schnütgen, Köln. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed