|

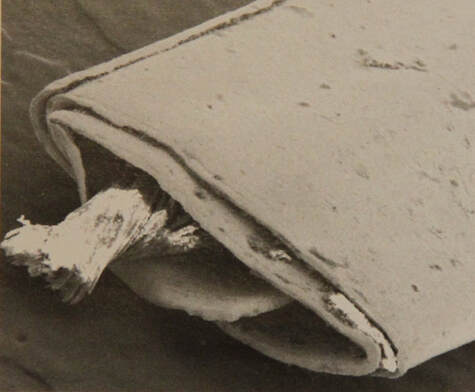

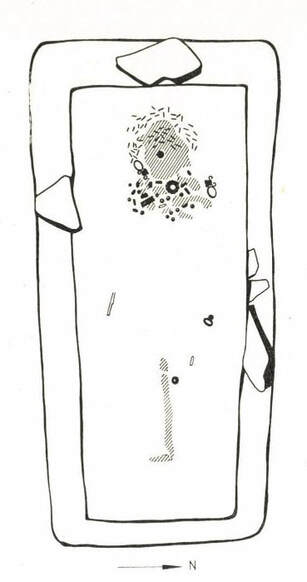

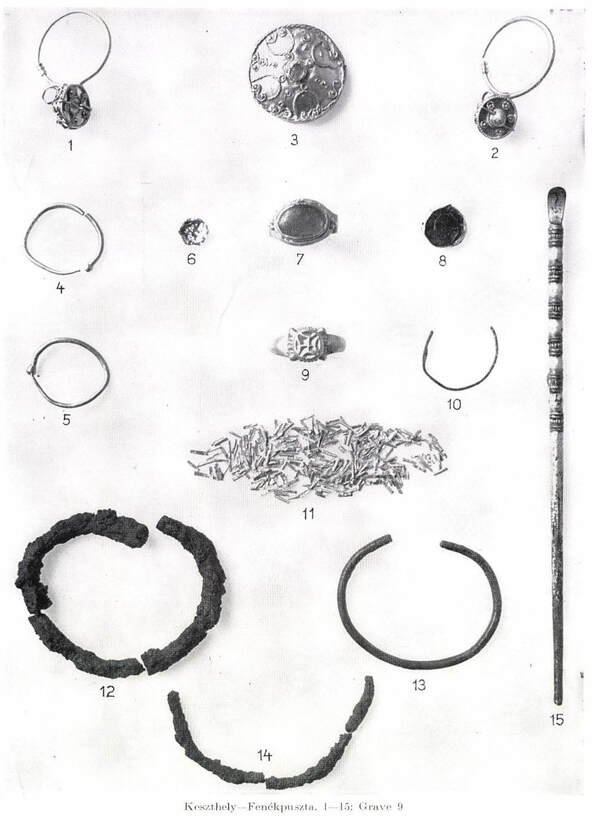

A couple of weeks ago, I showed you a curious piece of 12th century goldwork embroidery from Palermo, Sicily. It was made by sewing down golden tubes and then flattening them. In the meantime, I was able to find a bit more information on the embroidery. These golden tubes are not as rare as one might think. However, they were originally probably not used for embroidery, but for making hair nets in the sprang technique. Let's visit a couple of sarcophagi in Rome and some 'dark age' graves in Hungary! But first back to the fascinating golden tubes used in the royal workshops in Palermo in the 12th century. Above, you see a REM-picture of one of these little tubes. It was likely made by wrapping a sheet of pure gold foil around a 1mm thick wire. The wire was then carefully removed, and the resulting golden tube cut in smaller 'beads'. Each 'bead' is about 1.4 x 0.8 mm in size. They were sewn onto the samite fabric with a white thread (no specification mentioned, but probably silk). When the embroidery was completed, the tubes were hammered flat to probably achieve a continuous flat and shiny surface. This 'hammering' can also be observed on some of the Imperial vestments kept at Bamberg. It is not possible with modern gold threads. Similar golden tubes are regularly found in Roman burials in Italy and the wider Roman Empire. Some female burials contain up to 800 of these tiny golden elements. Sometimes fragments of fibres have also survived (linen and possibly silk). Comparing these finds with contemporary literary sources and wall-paintings has led to identifying them as the remains of reticulli (singular: reticulum). These were elaborate hair nets made in the sprang technique and either embellished with small golden tubes or made from gold thread all together. Although the Roman Empire ends in the West in AD 480, this isn't the end of the golden tubes. Burials dating to the 6th century on the territory of the Roman castellum of Keszthely-Fenékpuszta in Hungary contain the same golden tubes as seen in the earlier Roman graves from Italy. Interestingly, the Italian researchers seem to think that this particular hairstyle with a hair net originates in the Middle East. This fits well with the known Arab embroiderers stitching in the Royal workshops in Palermo in the 12th century. Maybe the use of golden tubes as beads in goldwork embroidery originates in the Middle East too. Maybe someone experimented with the golden tubes used in traditional hair nets and developed the embroidery technique. It would be worthwhile to investigate Middle Eastern goldwork embroidery from before the 12th century to see if pieces exist with these golden tubes. If anyone has additional information or ideas, please comment below! On a different note: I have started a Patreon page. You can show your support for this blog by buying me a coffee a month. Alternatively, you can give a little more to receive additional information with each blog post published. This week it will be my English translation of the Italian research paper. Future benefits will also include additional pictures of medieval goldwork embroidery and anything else I can come up with. The additional income generated through Patreon will allow me to visit more museums, read more books and pass the information on through future blog posts. Thank you very much for your support! Literature

Barkóczi, L., 1968. A 6th-century cemetry from Keszthely-Fenékpuszta. Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 20, 275–311. This reference can be donwloaded from this website. Bedini, A., Rapinesi, I.A., Ferro, D., 2004. Testimonianze di filati e ornamenti in oro nell'abbigliamento di eta'romana, in: Alfaro, A., Wild, J., Costa, B. (Eds.), Purpureae Vestes. Actas del I Symposium Internacional sobre Textiles y Tintes del Mediterráneo en época romana. Universiat de Valencia, Valencia, pp. 77–88. This reference can be downloaded from the Academia page of one of the authors. Járó, M., 2004. Goldfäden in den sizilischen (nachmaligen) Krönungsgewändern der Könige und Kaiser des Heiligen Römischen Reiches und im sogennanten Häubchen König Stephans von Ungarn - Ergebnisse wissenschaftlicher Untersuchungen, in: Seipel, W. (Ed.), Nobiles Officinae. Die königlichen Hofwerkstätten zu Palermo zur Zeit der Normannen und Staufer im 12. und 13. Jahrhundert. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Wien, pp. 311–318.

6 Comments

When I write my course descriptions, I usually include the size of the design. Most prospective students would then know which size hoop to bring. And it had not occurred to me that this is not necessarily the case when students are required to bring a traditional slate frame. As the number of 'please help me' emails soared the past couple of weeks, I thought it best to explain the process in a blog post. So here we go! When people already own a slate frame, it usually is the 24-inch/61 cm variety (this refers to the length of the cotton webbing attached). Not only is this the size used at the Royal School of Needlework, it also makes for a perfect combination with a pair of trestles. The frame is wide enough so that you can place a normal chair between the trestles and under your frame. The trestles and frame form a nice working table. The 24-inch slate frame is also large enough for most embroidery projects. However, if you need to travel by air, this frame is too big for your suitcase. Airlines mostly charge exorbitantly to transport your odd-sized frame (even when rolled together). So, what do you do? Buy a smaller slate frame especially for when you are travelling to courses and classes. Or when you do not want to invest in trestles. According to Jenny Adin-Christie, her slate frames up to the 15-inch variety can be used with a Lowery Workstand. I have been successfully using her 12-inch frame with Lowery Workstands in my travelling classroom (for instance at Glentleiten) and at home. Especially when you clamp the 'arms' (the part with the many holes) instead of the bars with the cotton webbing, the whole set-up becomes extremely stable. But what when they happen to have trestles at your class? Not a problem. They then usually also have some spare pieces of wood which can be temporarily attached to your slate frame. You basically elongate the two bars with the cotton webbing so that it then fits perfectly on top of a pair of trestles. Okay. That probably made sense. But now you still don't know how to go from the size of the design to the size of the slate frame required. It is basically the same as with a hoop. First question: size of the design. In the case of my class at the Alpine Experience in June, the design will be c. 30 x 13 cm. Next question: what are you planning to do with the finished piece? Do you want to frame it in a particular way which needs more or maybe less extra fabric around the edges. Add this to the size of the design. This is going to be the minimum size of the fabric that you are going to need to attach to your slate frame. In the case of the design for the Alpine Experience, you would probably not go any smaller than a 15-inch slate frame.

I hope you found this explanation useful! Last year, I was lucky enough to visit the Abegg Stiftung in Riggisberg, Switzerland when attending the CIETA conference in Zurich. Their permanent textile exhibition is worth a visit anytime. We were also allowed to visit the conservation laboratory. That was a real treat! And I was able to browse their publications. In my opinion, they are the gold standard when it comes to textile publications. But that comes at a cost. And them being in Switzerland doesn't help either. So being able to see before you buy was a real bonus. One of the books I had been ogling for a while was: "Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund" (=Medieval liturgical vestments from St. Nikolai in Stralsund) by Juliane von Fircks published in 2008. Let's explore! The website description of the contents of the book does not mention embroidery. It turns out that the majority of the liturgical vestments from Stralsund do not have embroidery (some do, bear with me). Instead, they are made from different combinations of exotic silks. Many are woven with gold threads made of strips of leather. The designs are amazing and very exotic. They were made between 1300 and the second half of the 15th century. Their origins are Central Asia, Persia, Spain, Italy and Northern Germany. The silks made in Central Asia were known as panni tartarici (Tartar cloths) and were very popular in Western Europe. The vestments made with them look a little like a crazy quilt :). Very colourful and luxurious. Not only does the book describe these silks and their history and manufacture in great detail, the cut of the vestments is also extensively studied (with the help of Birgit Krenz). The silks were imported and then tailored locally (Northern Germany). As the Tartar cloths were so expensive, it is fascinating to read how the tailors made the best use of every little scrap. As said, the majority of the vestments from Stralsund are not embroidered. Of the 39 catalogue entries, only three chasubles, one bursa, one substratorium, one wreath and one possible hat brim are embroidered. All date between AD 1400 and AD 1500. One of the chasubles shows the familiar nativity story according to Saint Bridget. Another chasuble shows a floral/foliage design partly made of leather padding on which freshwater pearls were sown. Not a technique we see often. The third chasuble has a beautifully rendered Christ on the cross. The silken embroidery in fine split stitches is stunning. The substratorium shows lettering stitched in cross stitch. Unlike today, the cross stitch was rather rare in the Middle Ages.

But my favourite embroidery is the angel playing the lute on the back of the bursa. The embroidery of the angel and the clouds consists of linen slips appliqued onto red woollen twill. The thick white contour of the clouds indicates that these were once edged with freshwater pearls. Foliage and small white flowers are stitched directly onto the red woollen twill to form the background. The angel wears a tunic stitched in double rows of membrane gold (now dull and silvery in appearance). The rows run vertically and are couched in a simple bricking pattern. By cleverly starting and stopping threads and by adding a few darker lines for the folds, the definition of the different parts of the garment is achieved. As always, this book from the Abegg Stiftung does not disappoint. It has many beautiful pictures and close-ups of the different textiles. The chapters explain how the treasury of St Nicolai survived to the present day. And how difficult it is to identify surviving pieces from church inventories. Each catalogue entry has very elaborate technical details. What threads were used and on what fabric (mostly with thread count). At present, the museum in Stralsund is closed for refurbishment so I do not know if (some of) these pieces are part of the permanent exhibition. Before I became an embroideress, I visited the museum as an archaeologist and analysed some animal bone found in the refectory of the Katharinenkloster. That was some 20 years ago ... Literatur Fircks, J. von, 2008. Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund. Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg. Grimm, J.M., 2005. Keine Lust zum Geschirrspülen? Auswertung der spätmittelalterlichen Tierknochen und der botanischen Reste aus der Remternische des Katharinenklosters in Stralsund. In I. Ericsson & R. Atzbach eds. Depotfunde aus Gebäude in Zentraleuropa (=Bamberger Kolloquien zur Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit 1), Berlin, 173-180. Although my library of books on medieval (goldwork) embroidery is filling more and more IVAR shelves, I still don't have everything :). Hunting publications down is a slow process. There's no central institution or website shouting new releases from the rooftop. Finding older publications often happens by reading through the footnotes and literature lists of publications already on my shelves. Especially chapters in books in which the subject is compared to other existing examples are really helpful. In the book on the Emperor's last clothes I showed you last week, I found some new-to-me information on the embroidery on the Imperial Regalia in Vienna, Austria. I've seen those. They are in a room very close to the spectacular or nué embroideries of the Order of the Golden Fleece. As the embroidered regalia are very old, they are not exactly in the limelight. The room is very dark. So the intriguing goldwork embroidery eludes probably most visitors. Let me introduce you to a very rare goldwork embroidery technique, I had never seen before. From the above picture I took, you can already tell that seeing details of the embroidery on the blue tunic is difficult due to the reduced lighting levels. The tunic was made in the first half of the 12th century in the Royal workshops of Palermo, Sicily. The red bottom seam contains embroidery in underside couching. This is seen in more pieces made in Palermo. The really intriguing embroidery is on the cuffs. From this poor picture I took, you can probably not instantly see what is so special about the goldwork embroidery technique used. If you look real closely, you might see that the embroidery is made of a kind of gold foil tubes sewn down like elongated beads and then flattened. The museum's website states that this is probably the only surviving piece in this technique. The caption in the museum does mention 'gold tubes' in the material list. But when you are not told where to look for them, it isn't easy to spot them in the dimly lit room.

I am most intriguied by this embroidery technique as I feel that these golden tubes were quite fragile and easily deformed. Why did the embroiderer choose this technique and not (underside) couching also in use at the same time in the Imperial workshops? Is the effect achieved so different? Is it quicker to stitch? Or is it easier to make gold tubes compared to gold thread? Any ideas? |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed