|

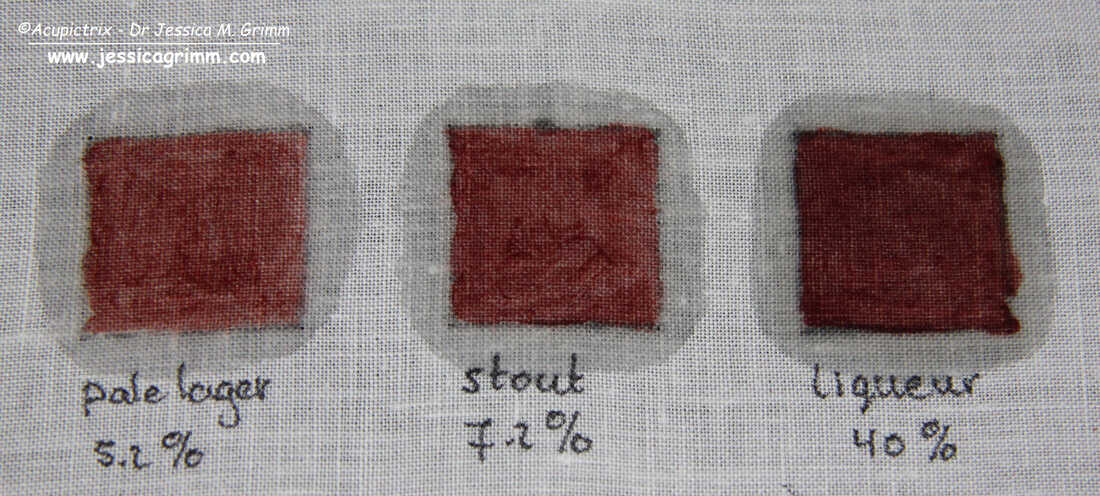

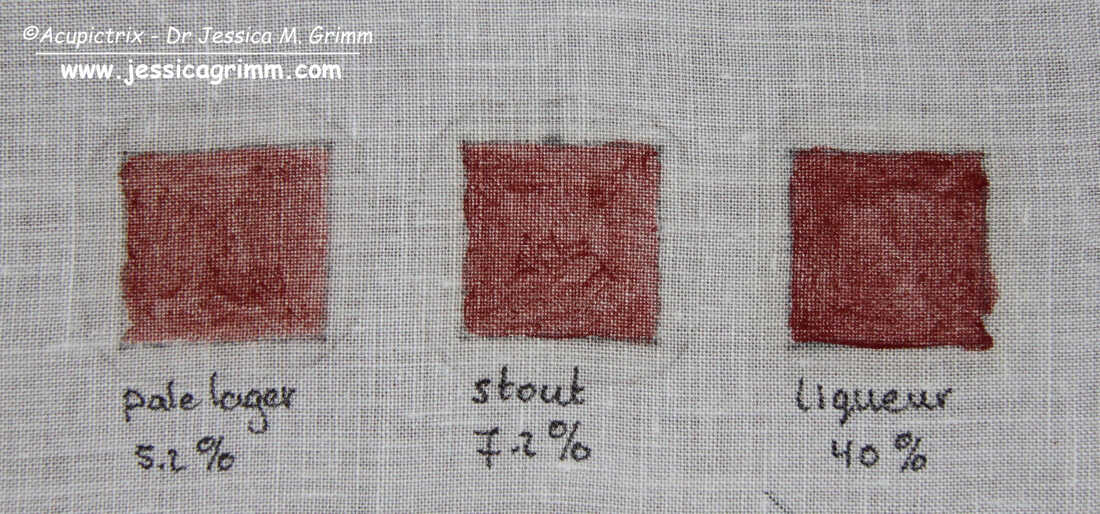

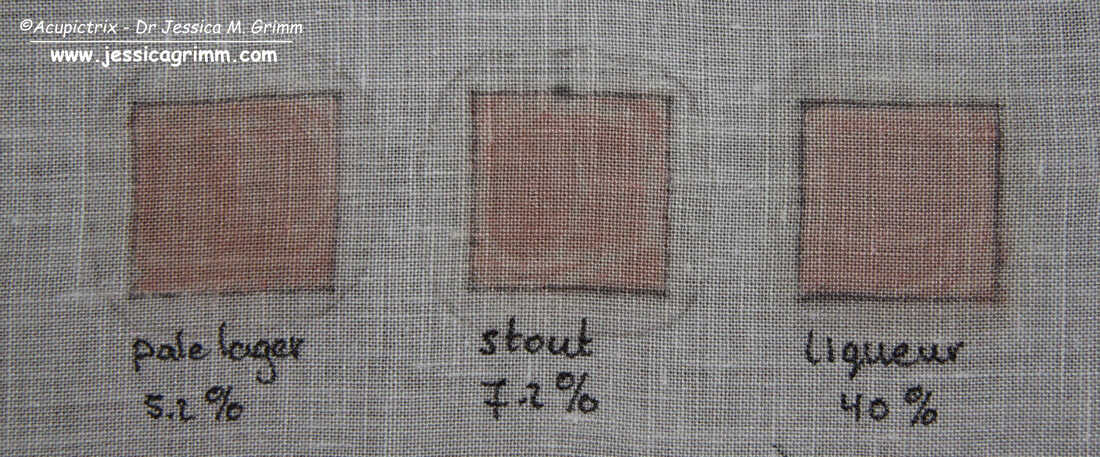

Asking for beer at 9:30h in the morning raised a few eyebrows next door at the abbey. Assuring Friar Markus that it was needed for an embroidery experiment did not improve things much. But it was the truth. What had happened? During my talk for MEDATS, I asked the audience for help with the madder conundrum. Whilst oil will do the trick, the greasy halo is very unsightly. Afterwards, I was contacted by Deborah Fox, who had done some dyeing experiments herself and she suggested alcohol. Ale was omnipresent in the Middle Ages as most water was too polluted to drink. I had always dismissed this option as I had a feeling that the hydrophobic madder would still think beer was too watery. However, I live next door to Ettal Abbey and they have been brewing and making liqueur for hundreds of years. Friar Markus was kind enough to sponsor the experiment with some homemade booze. For the experiment, I dissolved (or tried to dissolve) an 8th of a teaspoon of madder powder into a teaspoon of pale lager (5.2%), a stout (7.2%) and liqueur (40%). I drew three 3x3 cm rectangles with iron gall ink on my normal white embroidery linen. As I had expected, the pale lager and the stout were too watery for the madder's taste. It would not dissolve at all. But it did dissolve beautifully in the liqueur. And the smell was really nice too. Very herbal. I let the samples dry for a couple of hours. All did produce a bit of a halo but nothing too bad, I think. When the samples were completely dry, I brushed off the excess madder powder. Oh, dear! We get a very similar result to my experiments with only water. The madder just does not go into the linen enough as it does with the oil. And we still have a halo. This probably means that booze isn't the complete solution either. Maybe several substances were mixed with the madder powder to get the right result? More experiments are needed!

17 Comments

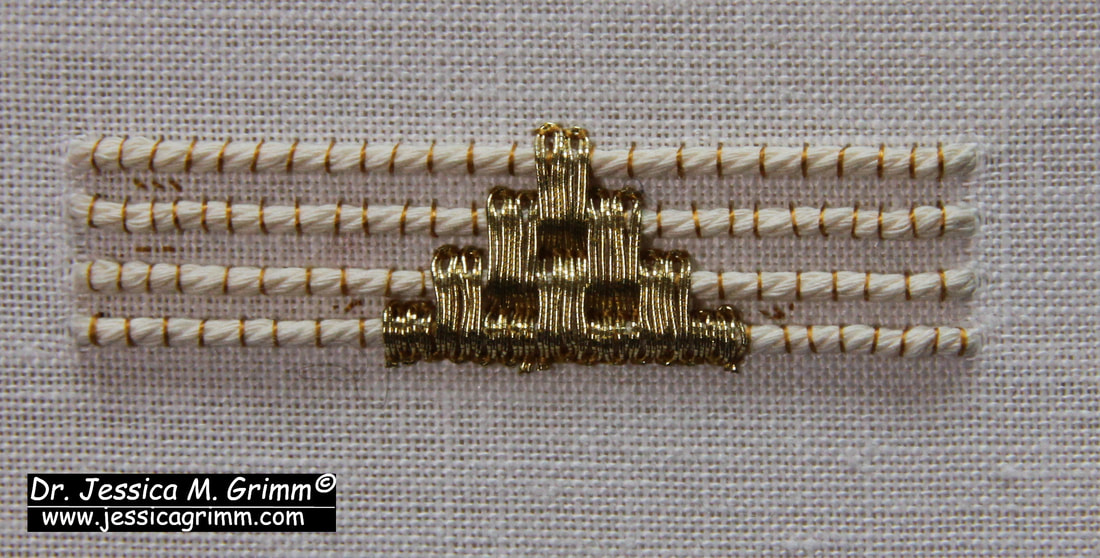

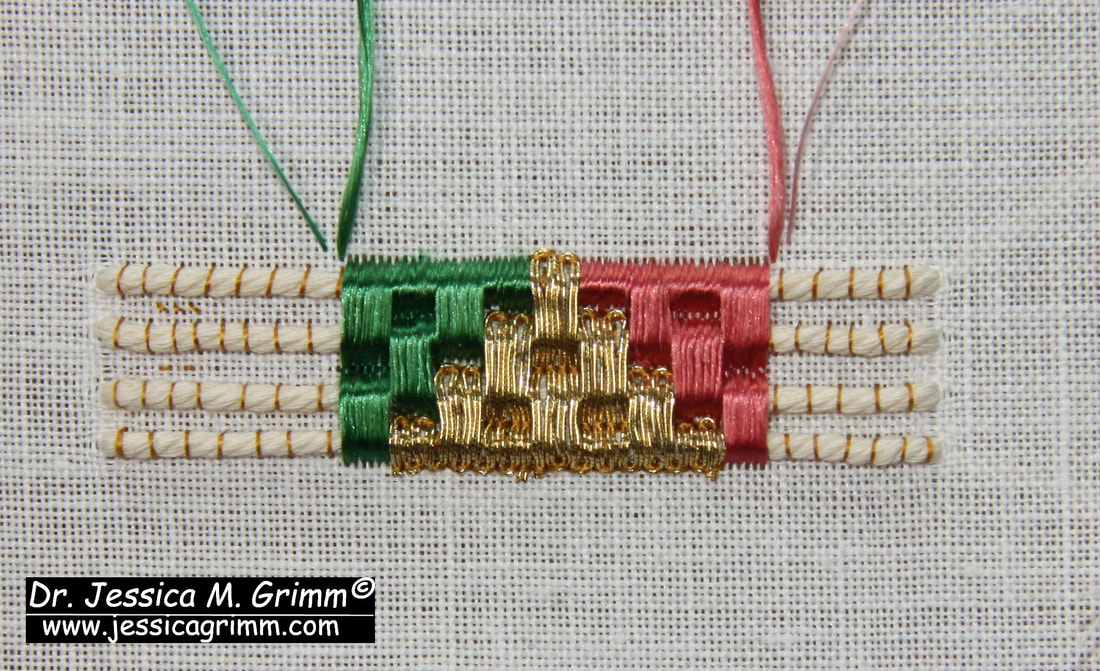

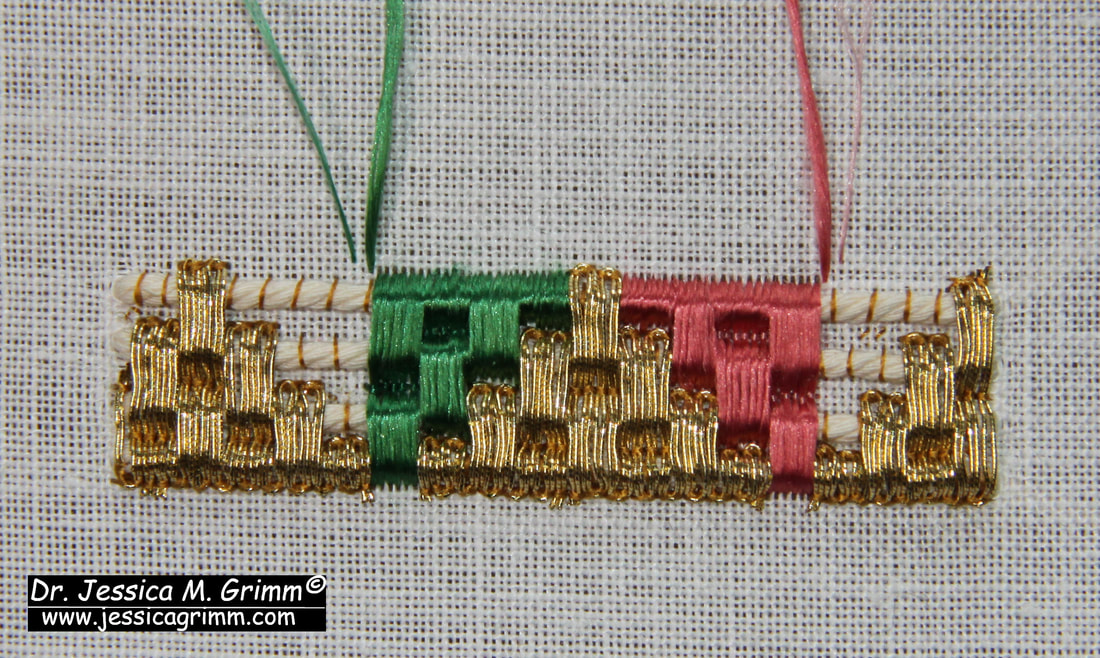

Two weeks ago, we looked at a late 15th century embroidered chasuble kept in the Domschatz of Fritzlar. It had these lovely textured bands or borders between the individual orphreys. The border is made my couching gold threads and coloured silks over string padding. It seems to be a very 'Central European' thing to do. The technique is not difficult at all and would look great in a modern piece of goldwork embroidery or on a piece of needlepoint/canvaswork. So, let me show you how it is done. As always, my Journeyman and Master Patrons can download a practical PDF with all the instructions from my Patreon page. Start by couching down four parallel rows of padding thread or string on your embroidery linen. I am working on a 46ct evenweave. For my couching thread, I used DeVere yarns #6 silk in a gold colour. By looking closely at the original, I could see that the gold threads were applied first followed by the silk. The golden triangles consists of 7 blocks of 4 rows of gold thread. The gold threads are couched down in pairs. I've used a passing thread #3 and the same DeVere yarns gold-coloured silk. Start from the middle. As the border is quite narrow, your gold threads need a lot of manipulation at the turns. Tweezers might come in handy and you might need an extra couching stitch in the turn. As silk is very slippery, I like to go over my couching stitches twice (i.e. place two couching stitches on top of each other). Alternatively, you can wax your silk thread. Remove any exess wax crumbs before you start to stitch. In the original, it becomes clear that the embroiderer went over the turns with their silks when they added the silken triangles. That's how I can see that the gold was stitched first. However, I don't like that as your silk snags so easily on the gold. Instead, I angled my needle under the turns. I've used Au ver a soie ovale with a matching colour DeVere yarns #6 for the couching. Start with only half a silken triangle. Measure the top of the golden triangle and match that for the silken triangles. Add golden triangles before finishing the silken triangles. Your threads will have a tendency to roll off the end of your string padding. In the original, this was solved with a red binding. Very clever indeed. And this is what my finished sample looks like. Wouldn't it be fun to figure out how to turn a 90 degree corner with this technique?

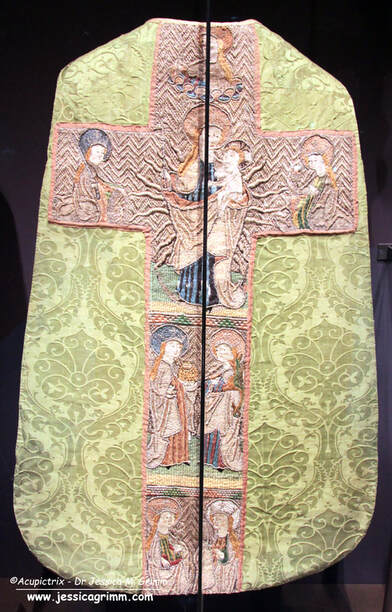

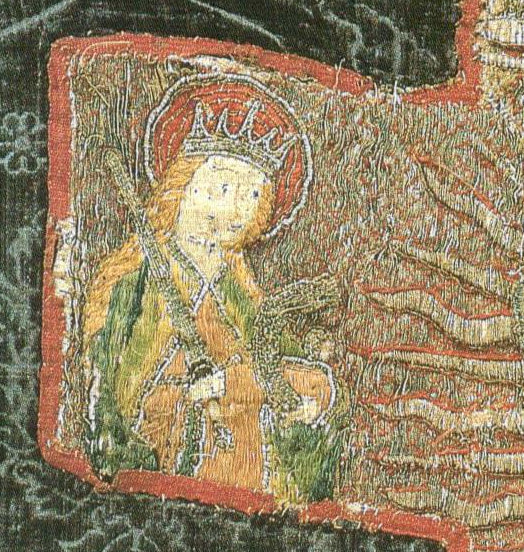

When we looked at the embroidered chasuble from Fritzlar with the Virgo inter Virgines iconography last week, I was sure that I would be able to find many Doppelgänger. I had seen this iconography many times before and I was quite sure that these pieces were all very similar. Nope. They are not. As soon as you start to look at these pieces in more detail you will find that they are all different. Either in the placement of the individual figures and/or in the embroidery techniques used. Now what does this mean? On the one hand, these pieces are readily recognisable as a group and on the other hand, they are all different. This, I think, must mean that there was a late medieval model book that was in use by embroiderers in Central Europe. As no medieval model books used by embroiderers seem to have survived, reconstructing one using actual medieval goldwork embroidery is pretty exciting. Here you see two typical embroidered chasuble crosses showing the Virgo inter Virgines from the late 15th century. The left chasuble was made in Austria in the second half of the 15th century and is kept at the Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts. The piece on the right is part of the private collection of the Bernheimer family. It was made in Southern Germany shortly before AD 1500. In both embroideries, Mary is depicted as the Madonna with child standing on the crescent moon with rays of light behind her. This 'Mondsichelmadonna' was very popular in the 15th century and refers to the Woman of the Apocalypse. On both embroidered chasubles the figures accompanying the Madonna in the large top orphrey are Catherine of Alexandria (with sword) on the left and Saint Barbara (with chalice) on the right. Everything else differs. No angel is crowning Mary on the Bernheimer chasuble. The figures in the two smaller orphreys below the Madonna differ for both embroideries too. On the left, we see Saint Apollonia (?) followed by Saint Ursula. On the right, we see Mary Magdalene followed by Catherine of Siena (?). When we look at the embroidery techniques used, there are differences but also many similarities. For starters, the colours used are very similar. There's mainly blue for Mary and a combination of green and orange for the other virgins. Both embroideries use the same diaper pattern for the golden background: open basket weave. Couched down with a yellow thread for the piece from Austria and couched down with a red thread for the piece from Southern Germany. The treatment of the halos is also identical. There's a layer of silken flat stitches as the base with a couched gold thread on top. The halo is edged with one of these composite threads: a thick textile yarn with a gold thread wound around it. This is sometimes called gold gimp in the German literature. These similarities in both iconography and embroidery techniques show that these pieces are made in the same geographical area. After all, Southern Germany shares a border with Austria. The differences show that the pieces were not made in the same town or guild. Likely, the customer could choose which additional figures to add to the central scene of the Madonna. These additional figures likely had some special meaning for the customer. As the iconography of the Virgo inter Virgines is strongly associated with convents, name days and patron saints of the nuns probably played a role here. And here you see the other main type of the Virgo inter Virgines iconography. The central top orphrey with the Madonna is very similar to that of the two previous examples (Catherine, Ursula, Barbara and Madonna). However, the two smaller orphreys below now show two saints each. We see Dorothea of Caesarea (basket) with Margaret the Virgin (dragon) and Saint Apollonia (thongs with tooth) with Mary Magdalene (ointment box). These two chasuble crosses are identical in their iconography. The treatment of Saint Ursula on a cloud above the Madonna is only seen on these two embroideries as far as I am aware. But there is more. There are other identical embroidery techniques too. See the bands that separate the different orphreys? They are made by couching silk and gold threads over horizontal string padding. And they are identical on both embroidered chasuble crosses. To me, this suggests that both embroideries were made in the same town. Will we ever find out which one? And when we look at the Saint Catherine's of all four embroidered chasuble crosses, they look pretty similar. How did this happen? In the 15th century, ecclesiastical embroidery had already evolved into mass production. Certain scenes were very popular and every self-respecting church wanted them. The 15th century also saw the invention of block book printing (major centres in the South of Germany) and the printing press (invented in Mainz, Central Germany). Likely, cheap block books with simple line drawings of the different Virgins existed in this geographical area too. These would have been used in the embroidery workshops as design inspiration. Designs would have been drawn free-hand or by using a grid to enlarge them more easily. Especially the faces differ between the various versions of a particular figure. This seems to be quite understandable as this is the hardest thing to get right in both drawing and subsequent embroidering.

By consequently digitizing these embroidered figures into line drawings and combining these with the used embroidery techniques, I have a feeling that it should be possible to group them. This hopefully leads to more precise provenances for these embroidered chasuble crosses. It should also help with the identification of incomplete figures on cut orphreys. I am planning to spend my summer holiday learning how to digitize with the help of Inkccape. In the meantime, I am collecting the Virgo inter Virgines embroideries on a Padlet for my Journeyman and Master Patrons to enjoy. Next week, we will work a practical sample based on the above embroideries! Late last year, I visited the Domschatz of Fritzlar. This is a small museum with several embroidered medieval textiles on display, which you can photograph as long as you don't use flash. The textiles are extremely well-lit and very close to the display case's glass. This means that you can examine them very well! The small town of Fritzlar itself is well worth a visit as it has these quintessential charming German medieval townhouses. Today, we will examine one of the embroidered chasubles on display. It was made in the late 15th century in Central Germany. Depending on the defenition, this can comprise parts of Hesse, parts of Franconia, the south of Lower Saxony, Saxony, Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt. As Fritzlar falls within this area, this is thus more or less a local production. Our poor chasuble unfortunately sits right behind the seam of two glass sheets ... The chasuble's iconography is an all-female affair (bar Baby Jesus). The central depiction shows Mary with baby Jesus standing on the moon crescent with rays of light behind them. To Mary's left, the bust of Catherine of Alexandria with sword and wheel. To the right, Saint Barbara with a chalice. Above, on the clouds (i.e. in heaven) sits the bust of Saint Ursula with an arrow. Below this central orphrey, there are two more orphreys with two female saints each. The top one shows Dorothea of Caesarea with a basket and Margaret the Virgin with her pet dragon. Below that is a cut orphrey with Saint Apollonia (thongs) and Mary Magdalene (ointment pot). All the women wear crowns and have a nimbus to identify them as saintly virgins. This concept of the Virgo inter Virgines (the virgin amongst the virgins) originates in Cologne and surrounding Westphalia, Germany. It is seen in various art forms between 1400 and 1530. Although it was popular with a wide range of audiences, it was specifically aimed at religious women in convents. We will examine other examples in next week's blog post. The chasuble has also a corresponding embroidered column on the front. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to see it. Although the embroidery looks a lot cruder than the refined or nue pieces from the Low Countries, it is actually quite high-quality. Many different techniques are being used for both the goldwork and the silk embroidery. For instance, the curley hair of Baby Jesus is made by overtwisting silk and couching it down. The silk embroidery in the faces is mostly vertical shaded brick stitching for the flesh with finely added detailed stitching for the facial features. These are not 'an official type of stitch'. The embroiderer painted with needle and thread to add the eyes, nose and mouth. The folds in the garments have been padded with string padding. The gold threads have been couched over these. Thick silken stitches accentuate these folds further. The rays of light behind Mary have also been padded heavily. But that's not all! Above, you see a detail of Saint Barbara with her tower. If you look closely, just to the left of her nimbus, you can see the string padding that's underneath the diaper pattern of the background. The double chevron pattern is created by couching over horizontally laid string padding. And we see something else that seems to be characteristic of some German embroideries: a thick textile thread wrapped in a thin metal thread. This metal thread is thinner than that used for the rest of the goldwork embroidery. Two of these 'gold gimp' threads are then twisted together and couched down along the edge of the neck opening of the garment and along the edge of the nimbus. I am wondering how they made this thread. Did they put some kind of glue on the thick textile core before they wrapped it tightly with the thin metal thread? I am also thinking that this metal thread is a membrane gold rather than a passing thread. It must be rather 'soft' to accept such tight and uniform coiling around the textile core. I have the suspicion that a passing thread would be too stiff or would show marked bends. Any thoughts? Literature

Weed, S.E., 2002. The Virgo inter virgines: Art and the devotion to virgin saints in the Low Countries and Germany, 1400--1530. Dissertation University of Pennsylvania. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed