|

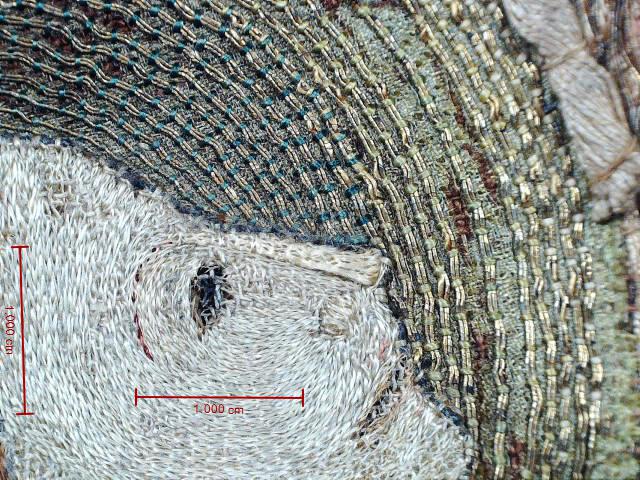

Last week's beautiful Bohemian chasuble cross was a bit large to discuss in a single blog post. And it turned out to be even more interesting. So here is part II. On a personal note: I rarely display the crucifixion scene prominently on my blog. Just like the early Christians I see an execution. However, this particular crucifixion has such beautiful embroidery and such an interesting alteration story to tell that it would be a shame not to show it to you. And there is a mystery padding technique I hope you might be able to identify. But above all, it prominently displays my favourite biblical power woman: Miriam of Magdala. Unlike Yeshua's male companions, Miriam of Magdala did not cowardly flee but endured watching Yeshua's execution. Her grief of losing her best friend is beautifully captured in this Bohemian embroidery. As is often the case in Central Europe, Miriam kneels and embraces the wooden column of the cross. She is all alone. Emphasising the special bond between Yeshua and her. Not an adultress (that's an invention by Pope Gregory I and was revised by Pope Paul VI) but a primary witness of the life and death of Yeshua. The very fine split stitch embroidery on the body of Yeshua has degraded to such an extent that the beautiful underdrawing has become visible. It is more than a simple line drawing and also shows shadows and many anatomical details. There is a red dye (probably madder) under the halo and on the beams of the cross (but avoiding the left arm). Clearly the work of a pro. The figure of Yeshua was worked as a slip and couched over the voided area of the sunny spiral background. You can see a gap between the top of the halo and that background. The halo has been elaborately padded with different shapes of parchment. If you look closely, you can also spot some later repairs. There are newer silk stitches in the crown of thorns, the hair and around the outline of the cross. You can even spot some newer goldthread under the right arm (left side of the picture). Also, the crude couching stitches visible on the right (left side of the body) are not original. And here is another detail. See the vertical line in the middle above the arm? That's a seam. Two different pieces of linen were joined here. The linen on the left is a bit finer than the linen on the right. It looks like a seam on both pieces was turned under and then the two pieces were slip stitched together. This seam was not visible when the embroidery was new. Because, if you look closely along the edge of the beam of the cross you can spot the remnants of a golden coloured fabric (probably silk). The order of work seems to have been to draw the cross on the linen background (pieced together from at least two pieces of linen) with ink and/or charcoal. Red paint was added to the beams of the cross. Then the golden background was stitched. Then the silk was appliqued over the beams of the cross and embroidered over (where the seam is, the silk of the beam lays on top of the spirals to straighten the beam and correct the line drawing). Then the figure was stitched to the background. Again, the red line along the beam and the blood splatters are later additions. The red of these later additions is much brighter than the original red silk used to edge the vertical beam (to the right of the halo). And here is the figure of Miriam of Magdala. For the most part, she is worked as a slip too. However, to get the perspective right, the last part of her right forearm is worked directly on the linen background of the sunny spirals. It even looks like there is a partial sunny spiral below the silken split stitches. It seems the embroiderer changed the design when the slip was attached. The colours are a little off too and the stitching isn't as neat as that of the rest of the arm. What is going on here? Here is another detail of the figure of Miriam of Magdala. As with the cross, there is a piece of green silk attached behind her halo. But something isn't quite right. The figure is appliqued onto the halo. The green silk is backed with a piece of coarse linen dyed a dark brown. It is not the same linen as seen behind the sunny spirals. The halo was thus not directly stitched onto the background linen on which the sunny spirals were stitched. And look at the gold thread. The gold thread in the halo (and that running along the seam of the headdress and the garment) is much shinier and hasn't oxidized in the same way as the gold thread of the sunny spirals. This is an indication that the thread in the halo is of a later date than that of the background. The thick crude white string at the top part of the halo would have been the padding for pearls. This again seems a later addition. And what about the broad padded seam along the edge of the headdress? What is it? How was it made? It seems to be stitched on top of the fine split stitches and could thus be a later addition as well. Do you recognise the technique? If so, please leave a comment below! And then there is her nose! When I first saw this, I was reminded of the parchment padded noses sometimes seen in Opus anglicanum (for instance: V&A 28A-1892). However, could it be that Miriam's nose was instead damaged at some point? The stitches are a little different and the colour of the silk seems a bit off too. The repair might account for the padded effect seen today. So. What the flip is going on? Well, I think that this beautiful Bohemian embroidery was taken apart when the current chasuble (or possibly an older predecessor with the same cut) was constructed. You see, when the original chasuble cross was stitched around AD 1380 the form of the chasuble it would have been appliqued onto was very different. It was much larger. Chasubles before the 13th-century were voluminous bell chasubles. Due to changes in the liturgy (elevation of the host) the priest needed more arm room and the chasuble became increasingly smaller. This eventually lead to the minimalist violin case shape of this 19th-century chasuble. This meant that older embroideries were too large and needed to be adapted. Often, they were simply cut off with little regard for the embroidered scenes.

Not so in this case. It seems that the figures were carefully taken off the sunny spiral background. The crucifixion cross was probably remodelled (cross beams and column shortened) and the silk was added. Miriam was given a new halo. She would have originally sat further down the column of the cross. When she had to be moved up, she either never had a halo or the halo could not be moved because it was part of the background (now possibly beneath her clothes). Due to the now shortened 'canvas' the pelican was moved down and now sits almost on top of Yeshua's halo. The figure of Yeshua is probably not quite in its original place either. A patch of newer gold thread next to his feet (big toe right foot) shows that originally something else was going on here. Maybe all the additional silk embroidery dates from this major remodelling too. All in all, it shows that this beautiful embroidery was valued and got a second lease of life. Literature Stolleis, K., 2001. Messgewänder aus deutschen Kirchenschätzen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Regensburg, Schnell & Steiner. Wenzel, K., 2016. Görlitzer Kasel. In: J. Fajt & M. Hörsch (eds.), Kaiser Karl IV, 1316-2016. Ausstellungskatalog. Nationalgalerie in Prag, p. 505-508.

6 Comments

Two weeks ago, I spent a very enjoyable day in the storeroom and the permanent exhibition of the cultural history museum in Görlitz, Germany. Curator Kai Wenzel facilitated my visit and together with my husband, we studied the five medieval embroideries kept at the museum. Görlitz lies in the historical region of Upper Lusatia and is bordered by the historical regions of Silesia and Bohemia. Today, these historical regions are divided up between Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. Most of the literature concerning medieval embroidery from these regions is a little older and not available in English. There is no comprehensive overview of all the medieval embroidery that has survived in modern museum collections and church parishes. Alfred Schellenberg published some preliminary overviews of what he called 'Silesian' embroidery in the late 1920s. His publications first drew my attention to this group of embroideries. As the map of Europe has changed quite a bit in this region after the Second World War, tracking the embroideries from his publications is a bit of a puzzle. Some are in Görlitz, others in several museums in Poland. By and by, I will try to track them all and arrange visits. Today, I'll introduce you to a chasuble cross that you can go see for yourself as it is displayed in the permanent exhibition of the cultural history museum in Görlitz. Meet 15th-century chasuble cross 61-03b on loan from the Evangelische Innenstadtgemeinde Görlitz. The chasuble was originally kept at the Peter and Paul church in Görlitz. As Martin Luther was not opposed to keeping using these catholic vestments after the reformation, this particular example is quite worn. Despite its worn state, it was transferred onto this newer chasuble in the 19th-century. This reminds us that these pieces were still being valued hundreds of years after they were originally made. To a modern viewer, their worn state makes them perhaps less worthy of display and proper research. Especially as there are contemporary paintings and sculptures which have survived in a much better state. These are often seen as more beautiful and they appeal to a larger audience. However, look closer and there is a lot to be discovered. This was once a beautiful and high-quality piece of embroidery. When you are a regular reader of this blog you might have a sneaky suspicion that you have seen a very similar chasuble cross before. Or even chasuble crosses. Well spotted! The scenes on this chasuble cross went viral in the 15th-century. They convey the story of Mary and baby Jesus in simple, easily recognisable pictures. The story reads like a comic book and usually starts with the angel telling Mary that she will be with child (Annunciation), pregnant Mary meets her pregnant cousin Elisabeth (Visitation), baby Jesus lies in the manger with Mary, Joseph and the as and oxen in attendance (Nativity), the Three Kings visit Mary and baby Jesus (Adoration of the Magi), circumcision of baby Jesus & presentation at the temple of baby Jesus. Depending on the space on the chasuble or local preferences other scenes could be added (Flight into Egypt, Massacre of the innocents, Jesus amongst the Doctors). Because these embroidered scenes are so generic, art historians can only broadly date and locate them on stylistic grounds. However, I have a feeling that when we look closely at the used embroidery techniques, we might be able to group some of these embroideries together. These groups might then represent different dates, geographical locations or even stitchers and workshops. The art historians can then try to argue which of these it is based on comparisons with other, better dated and located art forms. So let's start with this chasuble cross. Let's dissect the main scene with the Nativity. How many different embroidery techniques can you spot? - background and figures are worked in one go (versus figures are stitched separately and appliqued onto a separate background) this seems to be a characteristic that might zoom in on the dating of these pieces. - there's padded basketweave couching in the frame that goes partly around the scene. Gold threads (likely silver-gilt membrane with a white linen core) alternate with blue and pink coloured silk to form triangles. The string used for the padding has a strong Z-twist. This particular treatment of the frame around the orphrey is probably one of the characteristics on which basis groups of similar embroideries might be formed. - the now heavily corroded and worn golden background shows a very common couching pattern in red silk: closed basket weave (the little 'diamond' formed inside the 'weave' is filled with additional couching stitches). Although the couching pattern is the same for all orphreys, the silk used is yellow/white for the scene with the Annunciation and in the Visitation both this yellow/white and red are being used. The reason for the use of different colours and even two colours in one scene is not really apparent. It is seen in other embroideries too and might simply be the result of an embroiderer running out of a colour. It might also be that scenes like these were made in advance and then the customer could pick and choose the ones wanted. Note: I cannot prove that each scene was worked separately as the back of the embroidery cannot be inspected. The use of a diaper pattern instead of the 'sunny spirals' might also be a characteristic that is specific for the area of Upper Lusatia/Silesia. - there is gimped couching on the tracery of the architecture above the figures and on elements of the stable behind Mary. - the rim of Mary's halo, the seam of her cloak, the rim of the banner the angel is holding and the rim of Jesus' halo seem to be made from a piece of string that has been wrapped with a gold thread. This wrapped string is then couched down with a silken thread at regular intervals. This is another technique that likely groups some of these embroideries together. - Mary's cloak and Jesus's halo are stitched with two parallel gold threads couched down with silk in a bricking pattern. The design drawing underneath and fragments of silk present hint at further silken details once being present on top of the gold threads. This 'pseudo or nue' seems to be characteristic of 'German' embroideries. - the manger is stitched in burden stitch over a single gold thread. - some elements of Mary's and Joseph's clothing have been edged with two parallel gold threads. These seem to have been couched down at regular intervals with a twisted thread (possibly linen). - Mary's halo is filled with laid flat silk. The silk has been couched down with a single gold thread which has been couched down with the same silk. - the stable roof has received similar treatment, but in this case, two gold threads have been loosely twisted and then couched down with silk forming a zig-zag. - the same twisted thread can be found around the wings of the angel and along the tracery of the architecture. - although most of the silken stitches in the clothing and the fleshy parts of the figures has fallen out, it probably was some sort of long-and-short stitch with flat, untwisted silk. - the triangles above the tracery of the architecture are filled in with laid flat silk and couched down with a trellis of the same silk. There seems to have been an attempt at shading in the laid parts. - the round key-stone in the middle is made of silk and gold thread, but it is difficult to see what is going on exactly. The silk might be radial satin stitch which was then covered with parallel gold threads. - the grassy background is made of laid untwisted flat silk in different shades of green. On top, small flowers were stitched with coloured silks and gold thread. The whole silk embroidery was then couched down with a trellis made with a twisted thread (probably linen). - the hair of the angel and Jesus is made of an over-twisted thread (linen?). - the only other technique present on the chasuble cross is an appliqued piece of silk which forms the headdress of the Mohel (the Jewish cleric responsible for the circumcision). Note: the very fine horizontally spanned threads you might spot in the silken areas are modern conservation threads. If you spot anything else or have corrections on the above, please let me know! When I was looking at this piece in the museum, I exclaimed that it was one of these 'Bridget of Sweden' ones again. My husband contested as he was looking for the typical candle in Joseph's hand in the Nativity scene (our Joseph holds a staff; very common too). When I then started to search for pictures of other pieces on my laptop, I found a very similar chasuble cross in the Diocesan Museum of Bressanone in Italy (check out their virtual tour of the exhibition; also available in English and German!). This chasuble cross has instead of the scene with the Adoration of the Magi, the scene with the Flight into Egypt. Whilst the compositions are identical, the embroidery techniques used may differ. How did this piece end up in Northern Italy? Was it also locally made? This would mean that the geographical area in which identical embroideries were made in the 15th-century was much larger. Were embroideries produced in Lusatia/Silesia export products that were traded to Northern Italy? Or was the piece in Italy acquired through an antiquity dealer who perhaps sold it as an Italian embroidery? Kai Wenzel, the curator from the museum in Görlitz, is going to contact his colleague in Bressanone to see if they have more information on their piece. Update: Unfortunately no further information could be had on the piece in Italy.

Literature Schellenberg, A., 1927. Schlesische Textilkunst auf der Ausstellung Breslau-Scheitnig 1927. Der Cicerone 19, 477–484. Schellenberg, A., 1928. Mittelalterliche Messgewänder in Schlesien. Jahrbuch des schlesischen Museums für Kunstgewerbe und Altertümer 9, 79–94. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed