|

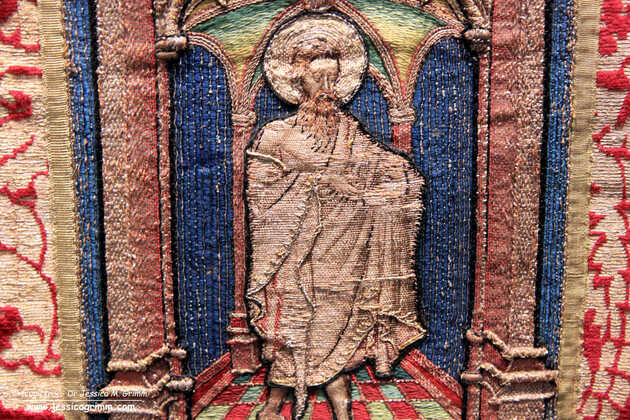

Not sure how many of you studied last week's pictures of the Schlosser set of vestments in great detail. If you did, you might have spotted the same oddities as I did. For starters, there's the 'enhancement' of the faces with oil paint. Not an unusual practice. The skill needed to work these super fine silken stitches to render the faces was something that the restorers of these late-medieval embroideries could no longer do from about the 17th century onwards. Another thing which you might have spotted was the cutting up of orphreys. Some were made less wide (breast pieces of the dalmatics) and others were turned into real patchwork pieces to cover the ends of the sleeves of the dalmatics. But there is something else. And it reminded me of a 2021 French article on or nué that I had read a while ago. Do you notice something odd about the embroidery techniques used for Mary's clothing? The 'red' is clearly or nué. But what about the 'blue'? Let's zoom in a bit! See?! The red is or nué. But the blue isn't. It is shaded brick stitching over pairs of gold threads. You could call this Burden Stitch. However, this stitch is commonly executed over a single gold thread. Odd. Since all of Mary's 'blue bits' are worked in this stitch you are forgiven for thinking that this is original. Luckily, John the Baptist can help us out here. And here is John the Baptist. His outer garment is almost completely executed in beautifully shaded or nué. But look at his left shoulder. There's a patch of this other stitch again. Executed in colours that come close to the original, but that are not the same. This 'bastard' Burden stitch is thus clearly not original. It was likely used to repair the original or nué in the mid-19th century. Probably executed by the Cologne vestment maker and his two daughters. Why did they not simply repair the area with true or nué?

To me, or nué is a relatively simple embroidery technique. It has absolutely never intimidated me. Neither does silk shading or shaded art blackwork. There's a common theme here: I can shade. It does not matter to me if I have to do the shading as part of blackwork, with long-and-short stitch or over pairs of gold threads. Neither does it bother me that or nué and blackwork are counted thread techniques and silk shading is not. It is all just shading to me. However, being in the embroidery teaching business, I soon learned that there are roughly two types of embroiderers: those that can shade and those that can't. Embroiderers who can shade a little, do not seem to exist :). Embroiderers who are, at first, intimidated by or nué often quickly get comfortable with the technique when they realise that it is just counted silk shading over a pair of gold threads. That is: embroiderers who can shade. Those that can't shade, cannot work or nué. These modern observations make the embroidery on the chasuble of the Schlosser vestment set all the more intriguing. The 'bastard' Burden stitch on Mary is very well shaded. The embroiderer could shade! Why then did he or she not work true or nué? Was it a time issue? Or did he or she not recognise the or nué technique in the first place? The latter could really have been the case. According to a comprehensive study by Astrid Castres published in 2021, the technique of or nué might have been completely lost for a couple of hundred years. It was then likely re-discovered in the second half of the 19th century. Just slightly after the restauration of the Schlosser vestments. Fascinating, don't you think? Literature Castres, A. (2021): Des premiers témoins médiévaux aux broderies des Clarisses de Mazamet : une petite histoire de l’or nué (XIVe-XXe siècle), Patrimoines du Sud 14, pp. 1–27.

3 Comments

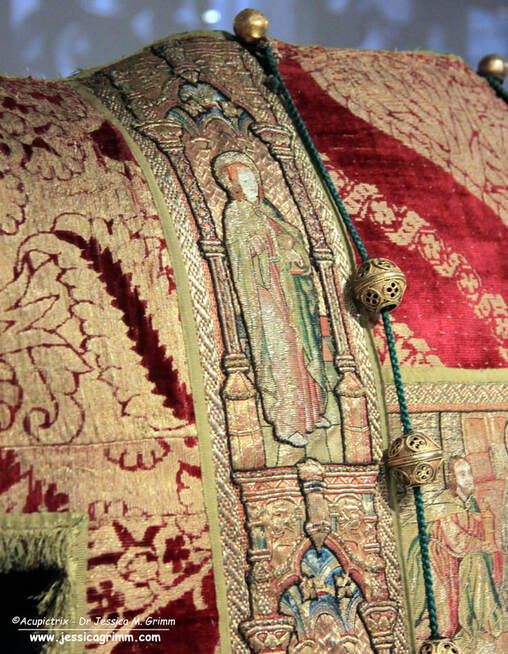

One of the highlights of my museum tour at the end of November last year, was the Dommuseum Frankfurt. It has nine medieval embroidered vestments on permanent display. Well worth a visit! At the beginning of the year, I showed you a green chasuble with embroideries from the mid-14th century and the second quarter 15th century made in Cologne. This time, I will introduce you to the Schlosser vestment set with embroideries made in both the Netherlands and Cologne. Both were made around AD 1460. The or nue, or shaded gold, used on the figures is very beautiful. Let's have a look. The Schlosser vestment set consists of a chasuble and two dalmatics. It was bought by Johann Friedrich Heinrich, known as Fritz Schlosser (1780-1851), a councillor from Frankfurt, in 1842/43 from the dealer Fontaine in Cologne. Fritz Schlosser asked his painter friend Edward von Steinle, a vestment maker in Cologne with his two daughters and painter and conservator Johann Anton Ramboux, also in Cologne, to restore the set. Apparently, the vestments were taken apart completely. Loose parts were affixed. But what really astonishes me, is that they treated the new gold threads with acid to make them look old. The vestment maker and his two daughters worked for about a year and were paid a 100 Taler (roughly €4243 today, according to some pretty tricky maths). This was not a living wage when compared to living costs around 1850 in this part of Germany. The vestment maker and his daughters must have had additional income. Thanks to the names and coats of arms embroidered onto the chasuble, we know where it originally came from. The names and coats of arms are of Merten Moench/Maarten Monicx (born in 's-Hertogenbosch (Netherlands), died 1466) councillor in Cologne and his wife Drutgin von den Groeven (died 1451). He probably donated the vestment set to a church in his hometown of 's-Hertogenbosch in 1460. Likely to the chapel of the Fraternity of Our Lady in the St. John's Cathedral. A couple of years later, Maarten also donated the orphreys for a cope. The fraternity had to provide for the fabric and the tailoring of the cope. Unfortunately, the cope has not survived. The curious thing about the embroideries on the Schlosser set of vestments is that they come from two different places. The orphreys on the chasuble were made in Cologne. We see a typical architectural background with saints standing on a tiled floor. However, instead of a golden background, the niche behind the figures consists of horizontally laid blue silk couched down with vertically laid gold. This is a technique not used in the Netherlands. Contrary, the embroideries on the dalmatics were made in the Netherlands. This time, the figures are completely stitched in or nue. The background of the niche in which the saints stand is filled with a basket weave diaper pattern in red. As the original silken stitches of the finely worked faces had fallen out, they were 'restored' with paint. Not sure if this was part of the 1842/43 restoration by the vestment maker of Cologne. Given that there were two accomplished painters in the group of restorers, it would not surprise me if one of them had wielded a brush. By taking a picture under an angle, you can clearly see the different slips that make up the orphreys on the dalmatic. The or nue on the robes of Saint John is absolutely stunning. However, these orphreys are the product of mass production. An identical Saint John can be found on the other dalmatic too. And Saint John isn't the only one. We also have doppelgänger for Saint Paul, Saint Peter, Simon the Zealot, Gregory the Great, James the Great and Saint Andrew. James the Great is even found in the same spot ... And this is only on the front. The backs of the vestments are not really accessible and have not been published either.

Given the fact that Merten Moench was born in what is now the Netherlands and died in what is now Germany, it is probably not that surprising that orphreys from both places were used in this set of vestments. It is likely that the family of Merten moved freely in the area that's now the border between Germany and the Netherlands. What does strike me as odd is that the orphreys of the chasuble on the one hand and the orphreys on the dalmatics on the other hand are quite different. Apparently, this did not matter much to the people who made, gifted and used these vestments in the middle of the 15th century. My Journeyman and Master Patrons find 37 additional pictures of the vestments on my Patreon page. Your monthly contributions made this research possible. Thank you very much! Literature Fircks, Juliane von (2010): Serienproduktion im Medium mittelalterlicher Stickerei - Holzschnitte als Vorlagenmaterial für eine Gruppe mittelrheinischer Kaselkreuze des 15. Jahrhunderts. In: Uta-Christiane Bergemann, Annemarie Stauffer (Eds.): Reiche Bilder. Aspekte zur Produktion und Funktion von Stickereien im Spätmittelalter. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 65–82. Koldeweij, J., Vandenbroeck, P., Vermet, B., 2001. Hieronymus Bosch - das Gesamtwerk: [Katalog]. Belser, Stuttgart. Stolleis, Karen (1992): Der Frankfurter Domschatz: Die Paramente. Liturgische Gewänder und Stickereien 14. bis 20. Jahrhundert. Band I. Frankfurt am Main: Waldemar Kramer. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed