|

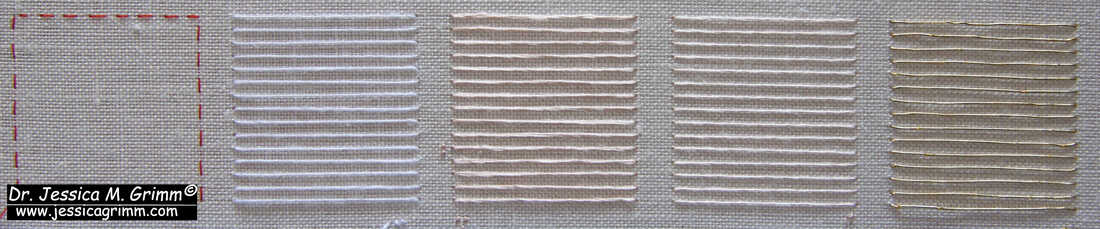

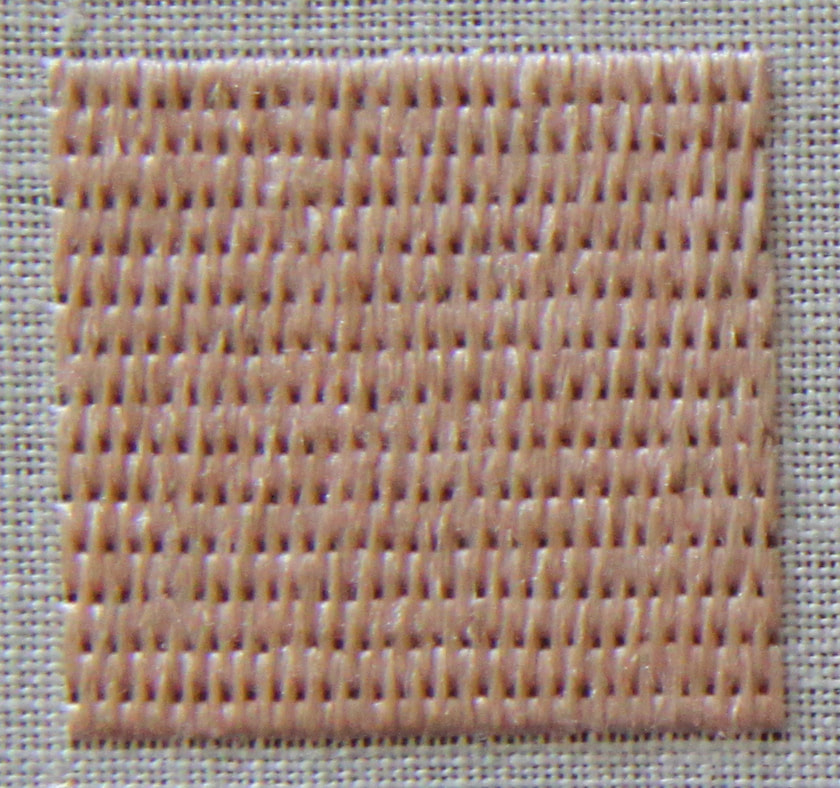

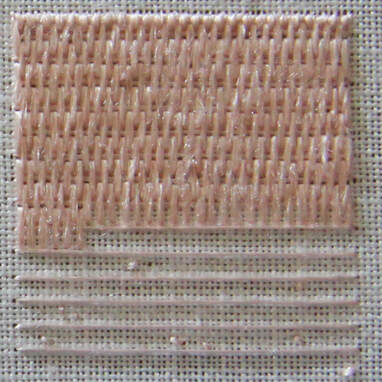

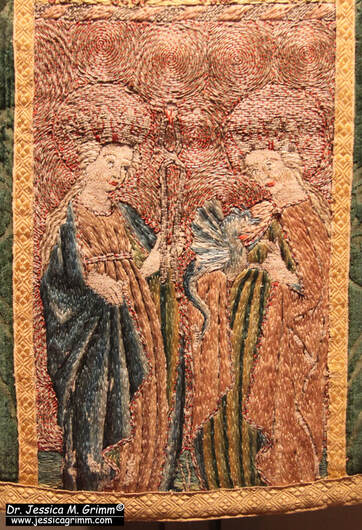

Adding an area of Burden Stitch to my orphrey a couple of weeks ago resulted in some questions and remarks regarding this lovely stitch. First up was the name. A stitch in use during the Middle Ages should probably not be named after a woman who lived in the 19th century. Good point. However, renaming (well-known) stitches is a bit tricky. How do you safeguard that people still know what you are talking about? I could start calling Burden Stitch something like 'Brick Stitch over a foundation thread/padding'. That's technically what Burden Stitch is. Next question: Was Brick Stitch called Brick Stitch during the Middle Ages? I don't know. As far as I am aware, and please correct me if I am wrong, the only technique for which the name can be traced to French accounts of the High Middle Ages is or nue. We could sure do with a Re rustica or Re metallica for embroidery. No such luck. And then there was the mermaid ... This mermaid. She is lovely and a bit problematic. Typically mermaid I would say :). Due to a free reference to the website of a textile conservation company in an article by Natalie Dupuis for Piecework magazine, this mermaid is quite well-known in the embroidery world. It was later mentioned on Cynthia Jackson's blog too. After all, it is one of the few free online resources with good pictures of the embroidery. Neither Natalie nor Cynthia mentioned the Burden Stitch in their articles as they focussed on a completely different aspect of the Fishmonger's Pall. Burden Stitch is only mentioned on the website of the conservation company. And I think it is a mistake. The skin of the mermaid (and Saint Peter) is not stitched in Burden Stitch. Identifying embroidery stitches from photographs can be really tricky. When I was alerted to the 'Burden Stitch' on the Fishmonger's Pall by one of my Patrons, I eventually got confused too. When I looked at the pictures, I saw Brick Stitch, not Burden Stitch. As mentioned above, they are similar. Burden Stitch has an added foundation or padding thread. Most needle painting or long-and-short we see in medieval embroidery is actually Brick Stitch or something close to the orderly needle painting as seen in Chinese embroidery. Free-form needle painting as taught by the Royal School of Needlework or Trish Burr, simply does not exist. The medieval embroiderer was a master craftsman and not an artist. Free expression in embroidery was not invented yet. In order to better understand what was going on on the Fishmonger's Pall, I decided to stitch up some samples. I used 46ct even-weave embroidery linen with Chinese flat silk. In order to cover the fabric nicely, I do go over each stitch twice. This gives a flatter result than when you use a double thread in the needle. For my foundation threads, I used: Barkonie linen thread 50/2, a double thread of the Chinese flat silk, a single thread of the Chinese flat silk and gilt Stech 80/90 (passing thread). Burden Stitch produces a textured surface. To me, skin should be smooth. As you can see from my samples, even the single thread of silk produces a textured surface. Furthermore, it is really hard not to catch any fibres of the foundation threads (not so with the Stech). No matter if you use a sharp or a blunt needle. But my biggest argument why the stitch seen on the Fishmonger's Pall is not a Burden Stitch is the fact that you always see the foundation thread in Burden Stitch. And we do not see one in the pristine areas of the skin of the mermaid. This rules out Burden Stitch for me. The V&A catalogue for the Opus anglicanum exhibition does also not mention Burden Stitch. I, therefore, think that the conservation company misnamed the stitch. What do you think? Have I missed something? Very well possible! Please chime in below. I will also organise a Zoom meeting on Saturday the 3rd of June for my Master Patrons to further discuss the mermaid and my experiments. Let's see what we can learn!

Literature Browne, C., G. Davies & M.A. Michael (eds), 2016. English medieval embroidery Opus Anglicanum. London: Victoria & Albert Museum.

8 Comments

Since I don't have any official information on the beautiful chasuble from the Diocesan Museum Freising, I am trying to find parallels with the help of my database. I've started with the figure of Saint Margaret. She is quite common in medieval embroidery, yet not too common. I was hoping to find a twin relatively easily. No such luck. Although I was able to collate 32 embroidered versions of Saint Margaret, they turned out to be remarkably diverse. And it quickly became clear that medieval people did not really know what a dragon looked like :). Renditions range from angry dogs to very elaborate dinosaurs. Still, there seems to be some regional agreement on what dragons look like. Let's explore! First things first: why does Margaret have a pet dragon? Margaret refused to renounce her Christianity and was tortured. At one point, she was swallowed by a dragon. The cross she carried gave the poor beast a sore tummy and Margaret was spit out. The story does not tell whether the dragon lived happily ever after. Margaret did not. She was decapitated and became a martyr. In iconography, Margaret is often depicted with a dragon and/or with a cross. My favourite depiction of Margaret can be found on the lappet of a Mitre held in the Rüstkammer, Dresden. My husband and I refer to it as 'the blue angry dog'. I think it is adorable. The interaction between Margaret and the blue angry dog makes me smile. And besides, the embroidery is stunning too! As said, the depiction of the dragon is very diverse in medieval embroidery. However, the depiction is remarkably uniform in England. Still, no two dragons are exactly the same. But the overall depiction is quite uniform. This is likely due to the fact that most of the surviving pieces date to a relatively short period: AD 1280-1375. That's classic Opus anglicanum. I love the elegance of this snake-like dragon and the action-pose of Margaret. I did find twin dragons on two pieces from Germany. It is a cute blue dragon sitting on Margaret's hand. Both renditions clearly had the same master copy. The embroideries belong to a whole corpus of embroideries that have relatively naive depictions of saints and biblical scenes. They often have a characteristic background of gold threads couched down in a 'sunny spiral' pattern. It is believed that these designs were possibly block-printed onto the linen and then embroidered.

Margaret's dragon would make a good study subject when you want to learn medieval embroidery. They come in all sorts and shapes and can be very elaborate. They can be easily turned into a lovely design on their own or with their 'owner' Margaret. My Journeyman and Master Patrons have access to a Padlet with all 32 embroidered depictions of Margaret and her pet dragon. Next week, we'll dive into the Burden stitch again. A little discussion on Patreon left me puzzled :). I ran a few experiments and I'll share the results with you next week! Currently, I am mainly working on my orphrey background. I will be teaching this design at the Creative Experiences in June. For the past couple of years, I have always combined written instructions with video. This seems to work well for my students. However, as the apartment next door is being gutted and then put back together again, my stitching and recording are very dependent on when the workmen are quiet :). So, let's check in on my progress. As you can see, the tiled floor is in, the wall with the window has been completed, the sky was added and the basis of cloth of gold with the diaper pattern is in. The cloth of gold needs some minor further embellishment. I was going to do that today, but alas, the workmen are plastering, and it sounds like they are standing right next to me :(. Let's aim for tomorrow! The diaper pattern has been a terrific candidate for demonstrating goldwork embroidery at my local open-air museum Glentleiten. People were fascinated by the simplicity of it and the lovely effect achieved. I even managed to get people hands-on involved. Two young girls, aged 8 (!), plunged right in and happily stitched a row on my orphrey. In the beginning, they stabbed around a bit before they found the correct hole with their needle. But I kid you not, after about 5 stitches their hand-eye coordination caught up and it all went very smoothly. By the way, I am happy for interested people to work on my orphrey. They can't really break anything. And it is much more fun than when you stitch a mock-up row on the side somewhere. Equally, I don't believe in doodle cloths. But that's a different story :). Would you be happy for strangers to have a go at your embroidery project? My orphrey background also contains a technique I had not tried before: Burden stitch over gold thread. It is used in the sky. I was familiar with Burden stitch but was a bit sceptical about the gold thread. When you are working the stitch it almost completely disappears below the silk. So, my thought was: "at least the texture is pretty". However, when the Burden stitched area catches the light it really glows! It never ceases the amaze me how little light, natural or artificial, goldwork embroidery needs to reveal its full potential.

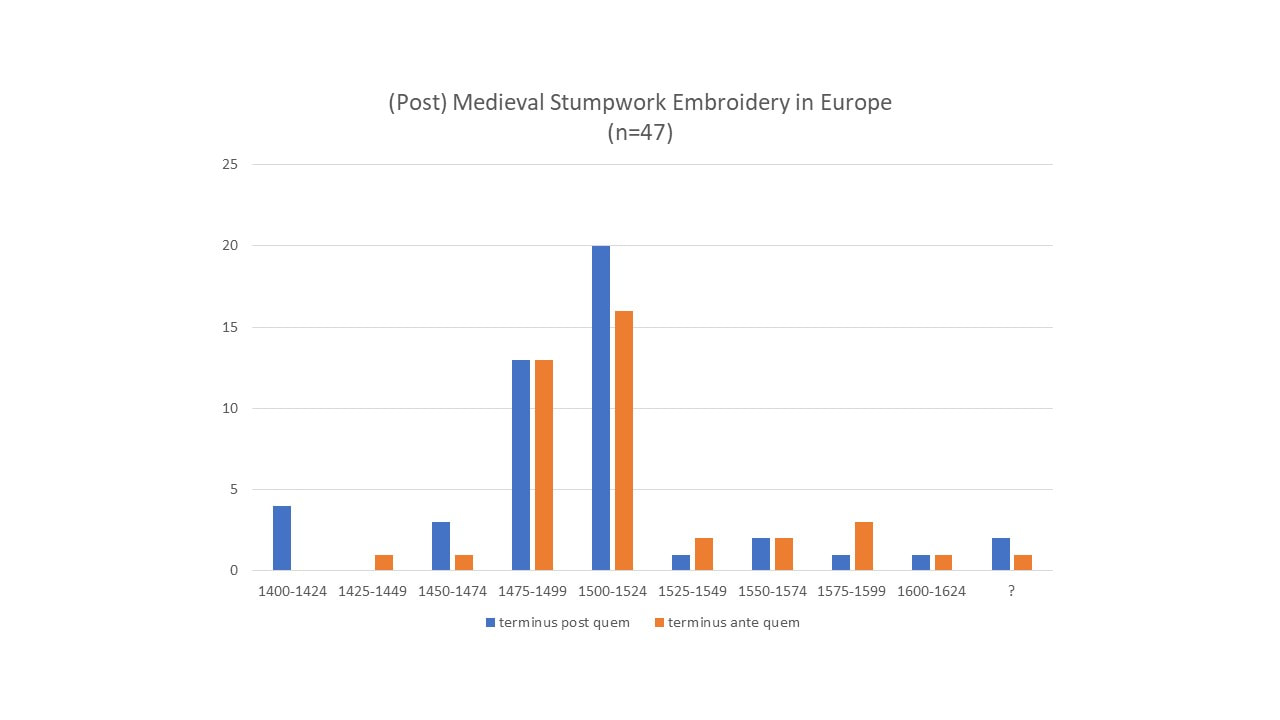

Have you ever worked Burden stitch over a gold thread in any of your projects? Would you like to have a go? My Journeyman and Master Patrons find handy PDF instructions on my Patreon page! Earlier this year, the Diocesan Museum Freising opened its doors again after extensive remodelling. As it is not too far from where I live, I decided to check it out in case any medieval embroidery was on display. It turned out that they have a stunning chasuble with very high-end embroidery on it. Unfortunately, there were no captions in the museum. I emailed them and wrote an official letter. To no avail. They never answered. Frustrating as this is, it is unfortunately, a reality when it comes to European museums. Museums in the UK or the USA are usually very helpful. Museums in Europe usually do not even bother to answer, let alone host me for a research visit. This undoubtedly is the result of how museums were and are financed in the respective countries. And with the 'distance' between lay people and experts. Despite having a doctorate in archaeology, being a professional embroiderer and having studied medieval goldwork embroidery for a number of years, this does not always make me an expert :). So, let's see what we can find out on our own about this stunning piece of embroidery! The chasuble cross on the back shows an interesting scene at the top: the mystical marriage of Saint Catherine. As far as I am aware, this is the only embroidered version of this particular episode. There are more embroidered scenes of the life of Catherine, but this one seems unique. The scene is flanked by two angles. One playing the harp and the other a lute. Below the central scene, Saint Margaret is depicted with the dragon. The beast playfully bites into her standard. The Saint at the bottom is Dorothea with her basket of flowers. Catherine, Margaret and Dorothea are known as the virgines capitales. As you can see, the orphrey has been cut at the top and at the bottom. Furthermore, we cannot see the front of the chasuble which might also have an orphrey. But the fact that the virgines capitales are usually four saints gives us an idea of what is missing: Saint Barbara with the tower. A further likely candidate is Mary Magdalene. As said, the embroidery is very high-end. The silk-shading is very finely executed. Both in the actual shading and in the regularity of the stitches. There's no or nue, which gives us our first hint of where the orphrey was made. Or nue is typically something of northwestern Europe (the Low Countries and Northern France) and Southern Europe. It was not really used in England or in Central Europe. As the stitching is very high-end and England does not seem to produce outstanding medieval embroideries after the heyday of Opus anglicanum, we can rule out England as the place of origin. This leaves Central Europe as the most likely candidate. The diaper pattern used in the background of all three sections of the orphrey is unusual too. I know of only one other instance where this pattern has been used: on an Italian orphrey with Bartholomew the Apostle in the Indianapolis Museum of Arts. Those orphreys are clearly Italian and date to AD 1500-1550. The orphreys on the chasuble from Freising are clearly not Italian. And the strong red couching stitches also support this (yellow is preferred in Italy). Another important characteristic of the embroidery on this orphrey is the padding. Especially the arches above the central scene and above Saint Margaret are very highly padded. It would not surprise me if a little bit of wood is hiding in the most-padded parts. In contrast, the figures and the rest of the scenes show very little padding. There's a relatively short period in the history of Central European goldwork when voluminous padding techniques (think stumpwork) really take off. Pieces belonging to this form of embroidery date from about AD 1400 until 1600 (some have a really wide date range assigned to them). However, when the dates are plotted for the 47 pieces in my database, we see that they cluster on either side of AD 1500. I, therefore, think that the orphreys on the Freising chasuble probably date between AD 1475 and AD 1525.

It is thus probably safe to say that the beautiful orphrey on the Freising chasuble was made somewhere in Central Europe around the turn of the 16th century. If you would like to see more pictures of this piece, please consider becoming a Journeyman or Master Patron. As a Journeyman or Master Patron you'll have instant access to a further 12 pictures of this piece. The monthly support of my Patrons enables me to keep this website running! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed