|

From the historical sources, we know that Utrecht and Amsterdam were important production centres of late-medieval goldwork embroidery in the Netherlands. The embroideries have survived in museum collections all over the world. But can we also identify embroidery production centres in the archaeological record? What would an archaeologist find if they would excavate your embroidery workspace 500-years from now? Would these archaeologists, by then living in a completely different world, understand that those rusty bits of metal were once your prized DOVO-scissors and your expensive hand-made Japanese needles? Luckily for them, you were probably active on Social Media :). But since there were no Social Media 500-years ago, what have archaeologists found that could have belonged to an embroidery master such as Jacob van Malborch? He was the chief embroiderer of a large embroidery workshop in Utrecht between AD 1500 and AD 1525. Thimbles! Yes, I know: 1) not all embroiderers use them and 2) other textile workers used them too. But they are pretty, fascinating and have survived in abundance. Let's explore them!

You are forgiven for thinking that a thimble is a thimble is a thimble. Nope. They are high-tech finger protectors. Their English name "thimble" sounds a bit like "thumb". And indeed, thimbles were probably first used for heavy-duty sewing through leather. You would push with your strongest digit: your thumb. Consequently, you would wear protection on your thumb. Not necessarily against pricking yourself, but more to protect your flesh from the strain of the pressure. That protection was likely a scrap of thick leather, but other materials such as wood, stone or bone were a good choice too. Would we recognise these make-shift proto-thimbles in the archaeological record? Probably not.

Real thimbles arrived in Europe in the 10th-century. They were brought to Europe through the spread of Islam and can be found in the archaeological record of the Iberian peninsula and the Balkan. Thimbles don't walk fast. It takes them several hundreds of years to conquer the rest of Europe. But from the 13th-century onwards they start to spread faster and faster. And although fine sewing and embroidery needles do not survive in the archaeological record, it is likely that these thimbles were the answer to bleeding fingers resulting from the use of metal needles.

These oldest thimbles produced in Europe were made of bronze and were cast. They are quite heavy with thick walls. They are tall, have a pointy shape and are hand punched or drilled on their sides. The top has no punches or is even open. This means that the sides, and not the top, of the thimble, were used to push the needle. Probably to save raw material, thimbles are hammered from a sheet of bronze or copper alloy from the late 14th- or 15th-century onwards. Slowly and by repeatedly heating the material, a thimble shape is achieved. You can recognize these thimbles by the characteristic folds they display at their base (see thimble above).

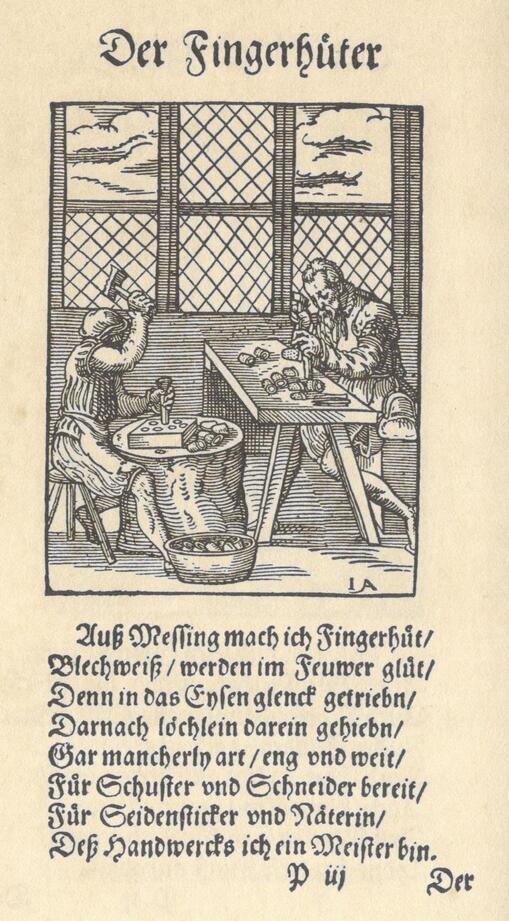

The next invention happens in Nuremberg, Germany. They invent a better way to make brass. Their type of brass is more elastic and easier to work with. Instead of hammering the thimble into shape, they start to press them into shape using increasingly smaller moulds (see picture above; the silk embroiderer is explicitly named as the receiver of these thimbles). These thimbles are of better quality. Nuremberg tried to protect their invention and people who knew the secret were prevented from leaving the town. It worked for a while and Nuremberg was the world-capital of thimble production in the 16th-century. But the guild tried to protect workers by forbidding inventions that made the slow hand-punching quicker. Once the secret of the composition of the brass was out, other places started to mechanise the punching process and took over production. But by then, the Middle Ages are over.

We know some of these "Fingerhütter" (makers of Fingerhüte=fingerhats=thimbles) by name thanks to the admission books of the Nürnberger 12-Brüderstiftungen. These were two almshouses for old men in Nuremberg. Each new brother was depicted whilst executing his profession. Sometimes interesting "gossip" about the particular brother is written down too. The oldest brother was depicted before AD 1414 and we see him drill holes into the thimbles. On his workbench, you see both closed thimbles and sewing rings. The next brother is Veit Schuster who died in AD 1592. We see him press the brass sheet in the mould. Wolf Laim (AD 1549-1621), Martin Winderlein (AD 1557-1627) and Nikolaus Zeitenberger (AD 1596-1667) are all punching their thimbles. The admission books also reveal that Martin was a quarrelsome man who could not be pacified with either food or drink. And Nikolaus did not die in the almshouse as he had become too much of a burden by being filthy and careless. Probably the result of dementia.

Literature Langendijk, C.A. & H.F. Boon, 1999. Vingerhoeden en naairingen uit de Amsterdamse bodem. Amsterdam, AWN. Mills, N., 2003. Medieval artefacts. Essex, Greenlight Publishing. Klomp, M., 2011. Metalen voorwerpen. In: M. Bartels (ed), Steden in Scherven. Zwolle, SPA.

I've uploaded a short video in which I model the different thimbles. Don't mind my hands. They suffer badly from all the anti-bacterial gels and the countless handwashing. No matter the amount of pampering :).

7 Comments

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed