|

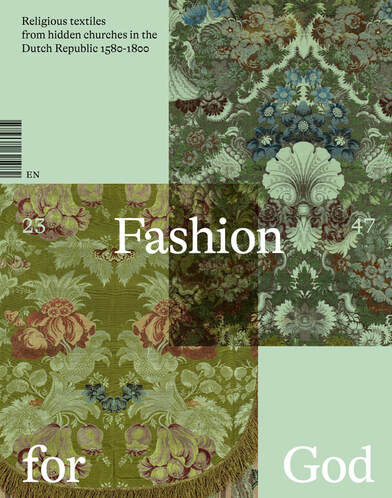

Before I let you know what I think of the catalogue accompanying the latest textile exhibition of Museum Catharijneconvent, I have some lovely announcements. Firstly, I have been re-invited to join the International Festival of Goldwork and Jewelery in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Two years ago, I sadly couldn't honour the invitation as I was very sick with Covid. So, fingers crossed that I stay healthy this time! Secondly, I have been notified by the Royal Dutch National Library that they will yearly archive a copy of my website and make it available in their collection. That's pretty cool too, I think! And now on to my book review proper. Last year, I visited the exhibition 'Fashion for God' (Religious textiles from the clandestine churches of the Northern Netherlands 1580-1800) in Museum Catharijneconvent in the Netherlands. It was the long-awaited sequel to 'Middeleeuwse Borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden' (medieval embroidery from the Netherlands) from 2015. And it was very much 'Dirty Dancing' and 'Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights' :). I only watched that sequel as Patrick Swayze had a teeny-tiny part in it. I only went to this exhibition as there would be a few medieval vestments on display that are hardly ever on display as their respective churches still own them. And it was a joy to be able to study them up close and take as many pictures, with sufficient light, as I liked. I also learned a lot about how these vestments survived and what the role of certain people and groups of people was. And I bought the catalogue for the sake of completion. Flicking through it before buying, it didn't exactly shout 'quality'. And now that I have read most of it, I don't know if I want to cry or start to laugh hysterically... The layout of the book, in my opinion, is a disaster. Pages with text have different background colours, the typeface is HUGE and pages with detailed pictures have been inserted at random as to imitate a fabric sample book. The paper of these 'fabric samples' is flimsy. There's an awful lot of empty space on the pages. The same information could have been printed on a fraction of the pages. Why this waste? Why not use a normal-size typeface and fill the pages properly? Use the freed-up space for close-up pictures of the embroidery or the fabrics, please! There are no close-up pictures of the embroidery in this book. Pretty odd for a book with embroidered textiles in it. The book consists of two parts. In the first part, there are five essays written by the Old Catholic bishop of Haarlem, a curator and a former curator of the museum, and two art historians specialising in (embroidered) textiles. Only one essay is well written. The others barely scratch the surface of the subject and just don't flow. One even has a pretty big omission/mistake regarding the types of gold thread used in medieval Dutch goldwork embroidery. But what is really missing from this part of the catalogue is a thorough essay on the embroidery and tailoring techniques used in the making of post-reformation catholic vestments. Why is this missing? After all, the socio-economic analysis shows that we move from (male) professional to (female) non-professional makers. Surely this is reflected in how things are being made. The second part of the book consists of the catalogue proper. There are 48 entries. Written details of the embroidery are very sparse. And since these are not illustrated with close-up pictures; good luck to the reader.

And the worst thing? The catalogue of the 2015 exhibition was only available in Dutch. Very disappointing for most of you and not good practice when you own a world-class collection. This one is available in English also. But why would you want one? At most, it serves as a list of textiles available in the Netherlands that you can then track down for proper study. Don't get me wrong. The exhibition itself was lovely. The fact that you can see many of the textiles up close and in sufficient light (often not even behind glass) is fantastic! And I really learned a lot about the religious women and some men who saved and preserved the late-medieval vestments and made new ones in the old style. But if you hoped to get a good impression of the exhibition through the catalogue, you will probably be pretty disappointed. When they did the medieval exhibition in 2015, all the pieces in the collection of the museum were photographed and made available in high-resolution online. Not so this time. So, you can't even use the paper catalogue as a starting point to enter better close-up pictures in their online catalogue. What a missed opportunity. Literature Beer, R. de & P. Arts (2023), Fashion for God. Religious textiles from northern Dutch hideaway churches 1580-1800, Waanders Uitgevers Zwolle/Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht.

3 Comments

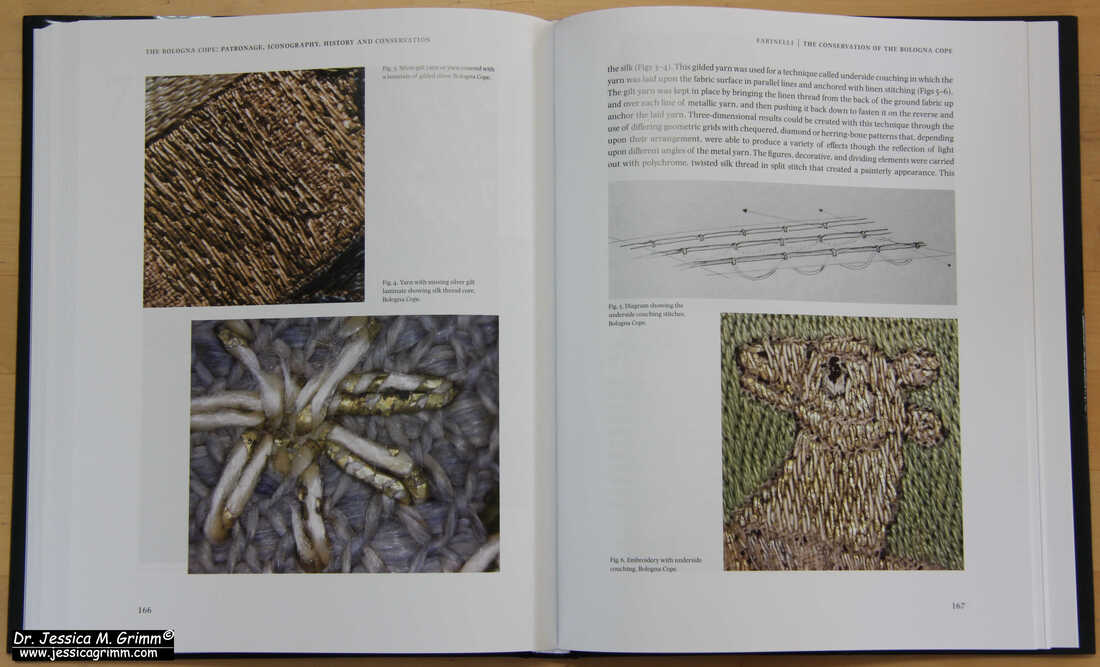

Maybe this blog post should come with the warning that there is a severe chance that you will spend money after reading it ... The Abegg-Stiftung has published a new book. In English this time! Some years ago, they conserved the altarpiece from El Burgo de Osma and the new book describes in incredible detail what they have found out about the embroidery. From the materials used to the order of work. It is so detailed that a skilled embroiderer or group of embroiderers could make a copy. Now that's a book worth having on your shelf. Even if it means that you will have to eat dry bread for some time to be able to afford it. We are still in the season of Lent so you will fit right in :). Let's explore! The embroidered altarpiece from El Burgo de Osma is the only one of its kind that has survived to the present day. It was made around AD 1460-1470 in Castille (Spain) for bishop Pedro the Montoya. The altarpiece is currently housed in the Art Institute of Chicago (Inv. no. 1927.1779a-b) and consists of two pieces. The top part shows four scenes: the Nativity on the left, Mary with baby Jesus in the middle with the Crucifixion above and the Adoration of the Magi on the right. The bottom piece shows the Resurrection in the middle flanked by three Apostles on each side. The top part measures 161,5 x 200,5 cm and the bottom part measures 89,5 x 202 cm. Both parts are all-over embroidered with gold and silver threads, coloured silks, spangles and seed pearls. The main part of the book consists of a 100-page chapter on embroidery materials and techniques written by Bettina Niekamp. She has identified over 200 different combinations of threads and stitches/techniques on the altarpiece. And she describes them in great detail. Together with the many detailed pictures in the book, you are able to identify them all. It will take you a while but it can be done. Amongst the embroidery techniques is the over-twisted silk technique for rendering realistic tree tops, grassy areas and dirt. This technique is well-known from 17th century English stumpwork. The many padding techniques are also intriguing. There are tubes made of linen fabric and then stuffed with wool to turn them into the base layer of columns. String is then added for extra texture before the actual goldwork embroidery commences. The embroidery is mainly executed in very skilfully shaded split stitch. But there is a form of or nue too. And for a more realistic depiction of certain details, multi-coloured threads were used. They were made by blending different silk filaments in the needle. The embroidery is also embellished with twists made of different numbers and combinations of passing thread. The book also has a whole section with full-page plates of the different parts of the embroidery. You can spend hours looking at the amazing detail. Further chapters describe the times and the life of bishop Montoya, its art historical context, the iconography in relation to the material and embroidery techniques used, late medieval embroidery in Aragon and a case study on vestments from Barcelona. With 427 pages, there is a lot to explore!

The book can be ordered directly from the Abegg-Stiftung in Switzerland. It costs CHF 85 + shipping. It does not seem to be available from the Art Institute of Chicago. The fact that this book was published in English instead of German is a real plus. Please let the Abegg-Stiftung know that we like more of that when you are ordering. They might end up translating some of their equally stunning older publications. My Journeyman Patrons can view a short video in which I flick through the book. Last year, I was lucky enough to visit the Abegg Stiftung in Riggisberg, Switzerland when attending the CIETA conference in Zurich. Their permanent textile exhibition is worth a visit anytime. We were also allowed to visit the conservation laboratory. That was a real treat! And I was able to browse their publications. In my opinion, they are the gold standard when it comes to textile publications. But that comes at a cost. And them being in Switzerland doesn't help either. So being able to see before you buy was a real bonus. One of the books I had been ogling for a while was: "Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund" (=Medieval liturgical vestments from St. Nikolai in Stralsund) by Juliane von Fircks published in 2008. Let's explore! The website description of the contents of the book does not mention embroidery. It turns out that the majority of the liturgical vestments from Stralsund do not have embroidery (some do, bear with me). Instead, they are made from different combinations of exotic silks. Many are woven with gold threads made of strips of leather. The designs are amazing and very exotic. They were made between 1300 and the second half of the 15th century. Their origins are Central Asia, Persia, Spain, Italy and Northern Germany. The silks made in Central Asia were known as panni tartarici (Tartar cloths) and were very popular in Western Europe. The vestments made with them look a little like a crazy quilt :). Very colourful and luxurious. Not only does the book describe these silks and their history and manufacture in great detail, the cut of the vestments is also extensively studied (with the help of Birgit Krenz). The silks were imported and then tailored locally (Northern Germany). As the Tartar cloths were so expensive, it is fascinating to read how the tailors made the best use of every little scrap. As said, the majority of the vestments from Stralsund are not embroidered. Of the 39 catalogue entries, only three chasubles, one bursa, one substratorium, one wreath and one possible hat brim are embroidered. All date between AD 1400 and AD 1500. One of the chasubles shows the familiar nativity story according to Saint Bridget. Another chasuble shows a floral/foliage design partly made of leather padding on which freshwater pearls were sown. Not a technique we see often. The third chasuble has a beautifully rendered Christ on the cross. The silken embroidery in fine split stitches is stunning. The substratorium shows lettering stitched in cross stitch. Unlike today, the cross stitch was rather rare in the Middle Ages.

But my favourite embroidery is the angel playing the lute on the back of the bursa. The embroidery of the angel and the clouds consists of linen slips appliqued onto red woollen twill. The thick white contour of the clouds indicates that these were once edged with freshwater pearls. Foliage and small white flowers are stitched directly onto the red woollen twill to form the background. The angel wears a tunic stitched in double rows of membrane gold (now dull and silvery in appearance). The rows run vertically and are couched in a simple bricking pattern. By cleverly starting and stopping threads and by adding a few darker lines for the folds, the definition of the different parts of the garment is achieved. As always, this book from the Abegg Stiftung does not disappoint. It has many beautiful pictures and close-ups of the different textiles. The chapters explain how the treasury of St Nicolai survived to the present day. And how difficult it is to identify surviving pieces from church inventories. Each catalogue entry has very elaborate technical details. What threads were used and on what fabric (mostly with thread count). At present, the museum in Stralsund is closed for refurbishment so I do not know if (some of) these pieces are part of the permanent exhibition. Before I became an embroideress, I visited the museum as an archaeologist and analysed some animal bone found in the refectory of the Katharinenkloster. That was some 20 years ago ... Literatur Fircks, J. von, 2008. Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund. Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg. Grimm, J.M., 2005. Keine Lust zum Geschirrspülen? Auswertung der spätmittelalterlichen Tierknochen und der botanischen Reste aus der Remternische des Katharinenklosters in Stralsund. In I. Ericsson & R. Atzbach eds. Depotfunde aus Gebäude in Zentraleuropa (=Bamberger Kolloquien zur Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit 1), Berlin, 173-180. As I am originally from the Netherlands and learned to do goldwork at the Royal School of Needlework in London, I was, until a couple of years ago, not very familiar with all the medieval goldwork embroidery that has survived in Germany. There is a lot! But it is sadly almost always published in German. Not very accessible for the worldwide embroidery community or indeed embroidery researchers from outside of Germany. The German embroidery community is very small and mainly interested in cross-stitch and whitework. I am thus sometimes a bit at a loss for whom these magnificent German publications were actually written. They are often full of very technical details. Things makers want to know, not necessarily your average archaeologist or (art) historian. Last year, I uncovered another one of these brilliant publications on the textile finds from the imperial and episcopal graves of Speyer Cathedral. Let me introduce you to some pretty amazing pieces! Firstly, we have the mantle of Philip of Swabia (1177-1208) made in the last quarter of the 12th or the early 13th century. On it are two medallions with goldwork embroidery. One shows Christ, the other Mary. The mantle's fabric and probably also the embroideries came from Byzantium. Philip had married Irene Angelina (1181-1208), a daughter of Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos (1156-1204). He thus had easy access to textile products from Byzantium. The embroidery is executed on a piece of fine samite with silk and gold threads. The goldwork is quite fine with about 40 parallel threads per centimetre. Interestingly, the gold threads are couched in normal surface couching, apart from the turns. These are done in underside couching (for instance also seen in the Reitermantle in Bamberg (DMB Inv.Nr. 3.3.0003)). For years, this combination of normal surface couching with a turn in underside couching eluded me. Why did they do that? When it came up in a discussion with Cindy Jackson recently, she immediately came up with a perfectly logical explanation: the turn is neater/easier. I had never thought of that. Although I know that many people struggle with making neat turns, I never found them hard or daunting to do. Doing an underside couching stitch with silk comes with the risk of breaking your couching thread. However, I perfectly understand that it is probably worth the risk when turns are not your forte. Mystery solved! Another spectacular find is a pair of episcopal socks from one of the bishop's graves. The embroidery is completely executed in underside couching. It is therefore possible that these luxury socks were made in England around the year 1200. However, as we have seen in the contemporary mantle of Philip of Swabia, the underside couching technique was by no means exclusively practised in England. My gut feeling is that underside couching = Opus anglicanum = England is sometimes a little too eagerly applied for goldwork embroidery found in continental Europe.

Apart from describing the original excavations in the early 20th century, the publication also has very good chapters on medieval textile techniques (weaving, finger looping and tablet weaving). Another chapter compares the finds from Speyer with contemporary finds from elsewhere. The chapters on the scientific investigations of the finds are also very good with a whole chapter on the gold threads. If you are interested in archaeological textiles (some with goldwork embroidery), this book is for you. As the book is a little older, you can sometimes find it second-hand. However, you might be able to get it through a library. Literature Herget, M., 2011: Des Kaisers letzte Kleider. Neue Untersuchungen zu den organischen Funden aus den Herrschergräbern im Dom zu Speyer, Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer. Today I am going to introduce a new book on Opus anglicanum to you. One of my students posted about it in the Medieval Embroidery Study Group. As the book is written in English, the language used by most people in the international embroidery scene, these books are too important to ignore. They have the potential to become gospel. At € 125 + shipping, the book isn't exactly a bargain. So, let's explore its contents together so that you can make an informed decision as to whether to buy it or not. The Bologna Cope: Patronage, iconography, history and conservation is edited by M.A. Michael and is the second volume in the series "Studies in English Medieval Embroidery". The book can be ordered through Brepols publishers. As the Bologna cope is held in an Italian museum, the book's chapters are mainly written by Italian scholars. But as the editor is from the UK, the book is published in English. Italy has many splendid medieval embroideries and a large body of literature about them. However, it is all published in Italian. Not a language most of us are fluent enough in. The book starts with a general introduction to the subject. Those of you who went to see the Opus anglicanum exhibition in the Victoria & Albert Museum a couple of years ago, probably remember the Bologna cope as it was displayed right at the entrance. This first chapter also briefly introduces us to a few other embroidered vestments held in Italy. Neither the iconography on these pieces nor their embroidery techniques are described. The pictures are mostly not detailed enough to fill in the blanks. The second chapter is by M.A. Michael himself and mainly deals with stylistic comparisons between the design of the cope and several other works of contemporary art. It does have a rather good overview of the historical sources containing references to the makers and dealers in Opus anglicanum. However, a lot remains unclear as the dealers can often not be confidently separated from the makers. If you want to know more about the makers of Opus anglicanum, this chapter is not going to add much. A large chapter is devoted to the iconography of the cope. It is illustrated with many pictures of the embroidery. However, as many of the scenes are quite large, the pictures are mostly not detailed enough to learn more about the embroidery. Only a hand full provide enough detail. The next two chapters will not be of interest to most embroiderers. One chapter deals with the possible references made to this cope in the inventories of the Friars Preachers in Bologna. And the other chapter deals with the publication and exhibition history of the cope. The 6th chapter sounds very promising: "Textiles and Embroidery in Italy between 1200 and 1300". Unfortunately, the majority is on the fabrics and not on the embroidery. And don't be fooled. We are not getting an overview of embroidered pieces made in Italy in the 13th-century. It only briefly explores the remaining textiles associated with Pope Benedict XI (donor of the Bologna cope) and his predecessor Boniface VIII. Are there no other 13th-century Italian embroideries? There are! They can be found in the Victoria & Albert Museum, in the Domschatz in Aachen, in the Keir Collection and in the Museo Episcopal Vic. As I don't read Italian very well, my research into Italian medieval embroidery is slow and far from complete. This chapter should have been an excellent opportunity to thoroughly introduce a non-Italian reading audience to the topic. But it is the last chapter that really has me fuming: "The conservation of the Bologna cope". This chapter should contain a section on the materials and techniques used to create the embroidery on the cope. It doesn't. We are only told that the embroidery is executed on two layers of linen. Count, please! The gold threads are made of silver gilt foil wrapped around a silken core. Composition of the metals? Spun directions? Colour of silken core? Thickness? Any details of the silken threads used for the split stitch embroidery? Length of stitches? The chapter does contain a few close-ups and a few macro images (no scale!). But that is all. What a missed opportunity.

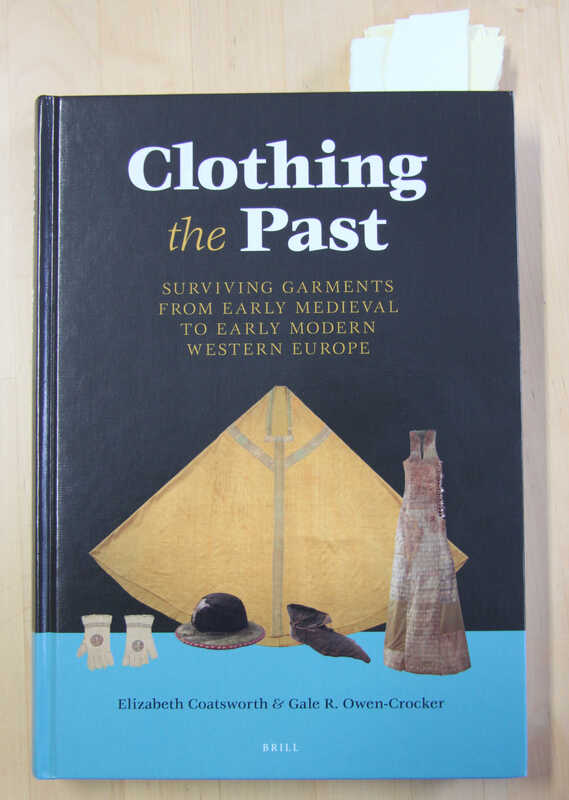

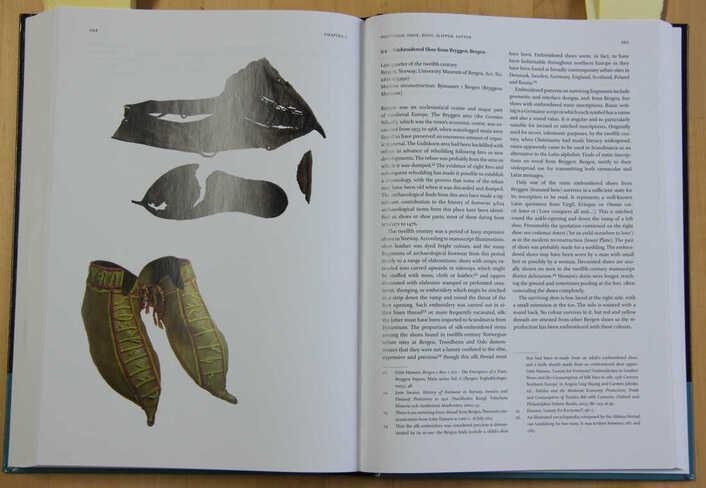

All in all, this book is, at best, a coffee table book. The research essays are not brilliant. For the embroiderer, this book is a huge disappointment and a missed opportunity. No information is added compared to the catalogue entry in "English Medieval Embroidery" from 2016. Should you buy the book? Only if Opus anglicanum is really your thing and you have the cash to spare. Instead, save up for the publications of the Abegg Stiftung and perhaps take some German lessons? Literature Browne, C., Davies, G., Michael, M.A. (Eds.), 2016. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press, New Haven. Michael, M.A. (Ed.), 2022. The Bologna Cope: Patronage, iconography, history and conservation. Studies in English medieval embroidery II. Harvey Miller, London. Today, I am going to review a book that has been published about four years ago. Just like me, you might have missed this one; it isn't primarily about embroidery. In addition, with a selling price of €215/$247, it is rather expensive. It is always nice to read a bit more about an expensive book before you commit. The full title of the book is: Clothing the Past: surviving garments from Early Medieval to Early Modern Western Europe. The authors, Elizabeth Coatsworth and Gale R. Owen-Crocker are leading experts in the field of medieval studies and medieval textiles. So let's explore what's between the covers of this 435-page book! As said, this book is not primarily on embroidery. But since textiles of the upper classes were often decorated with embroidery AND these textiles had a better chance of survival, quite a few pieces with lovely embroidery are described in this book. This difference in survival chances between textiles of different social groups is discussed in the first chapter of the book: the General Introduction. One of the strengths of this publication is that the authors have tried to include as many 'everyday clothes' worn by 'everyday people' as possible. This has resulted in the inclusion of many archaeological finds from York (UK), Monasterio de Santa Maria La Real de Huelgas (Spain), Bocksten (Sweden) and Herjolfsnes cemetery (Greenland). Preservation issues regarding burial conditions in archaeological excavations (including tombs) are also touched upon. For instance, linen does not usually survive in an archaeological context; it rots away. Hence the misconception about medieval people not wearing underwear. In total, 'portraits' of about a hundred textile pieces are grouped together in 10 chapters. We move from head to toe and from outer garments to socks and underpants. Each of these chapters starts with an introduction in which relationships, similarities and differences between the pieces in a particular chapter are discussed. Each chapter has at least several embroidered pieces in them. New to me were the textiles from the Royal tombs in the Monasterio de Santa Maria La Real de Huelgas. Have a look at this spectacularly embroidered and beaded Spanish Birette found in the tomb of Prince Fernando de la Cerda (AD 1255-1275). Each 'portrait' consists of a picture or pictures of the piece and a description with plenty of citations for further reading. I got the feeling that the authors were more comfortable with sewing than with embroidery. The construction of the different garments is discussed in greater detail than the embroidery. For me, the gold standard of describing embroidered pieces are to be found in the publications of the Abegg Stiftung. However, as this book is published in English but contains so many pieces originally published in German, a Scandinavian language, French or Spanish you are bound to find information that is new to you. And when you then decide to dive into the original publications you have an idea of what they are about. So: is this book for you? That's a little difficult to answer. For those of you who like to look at close-up pictures of pretty embroidery for inspiration; this book disappoints. There are no such pictures and the description of the embroidery is too flimsy. However, if you are interested in medieval textiles in general and archaeological textiles in particular; this book is for you! I have read it from cover to cover and placed many post-its throughout the book for revisiting later (and I've ordered suggested literature through second-hand websites!). As the book is quite expensive and has such a large scope, you might want to try to order it through your library first and then decide on a possible purchase.

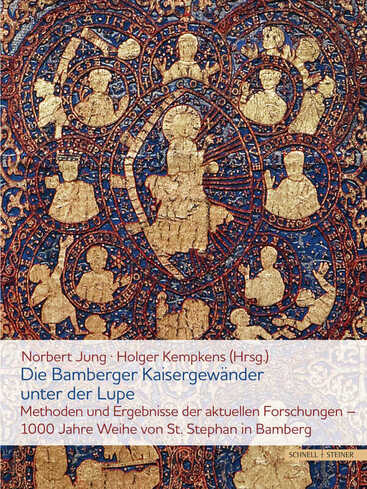

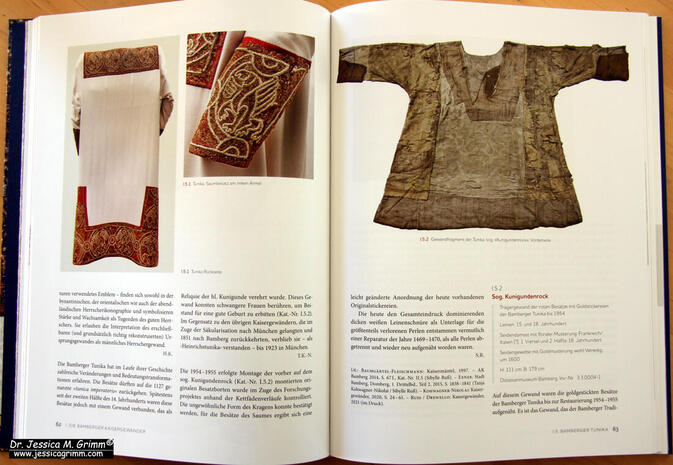

Coatsworth, E., Owen-Crocker, G.R., 2018. Clothing the past: Surviving garments from early medieval to early modern Western Europe. Brill, Leiden. On Friday I got an email from DHL saying that they would finally deliver the next volume in the monograph series on the Imperial Vestments the next day. And they did! Probably due to the worldwide paper crisis, this book has been on pre-order for more than a year. The third, and last volume, is still on pre-order and is said to be released before the end of the year. Since there are three books on the topic, all written in German, it can be a little difficult to determine which ones to order. Read on for my review of the second volume: Die Bamberger Kaisergewänder unter der Lupe - Methoden und Ergebnisse der aktuelle Forschungen (The Imperial Vestments under scrutiny - methods and results of the current research project). When I pre-ordered all three volumes in the series, I wasn't quite sure what to expect from each of them. Reading through the introduction of this second volume, I now understand that this volume was intended as the catalogue for the recent exhibition in the Diocesan Museum Bamberg. This means that the first part of the book (p. 14-97) is the catalogue entries for the exhibits. In essence, this is a summary of the first volume: Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung which I reviewed a while back. Whilst this part contains some new pictures not seen in the first volume, these mainly depict written sources. A tiny part of the book, pages 101-115, describes the art-technological and material science research conducted on the Imperial Vestments. I assume this is a summary of the third and last volume that hopefully gets published before the end of the year. Personally, this is the volume I am looking forward to the most as it promises to hold a lot of technical information important to us as embroiderers. The "summary" on pages 101-115 does whet my appetite but is not meaty enough to satisfy my appetite. The second half of the book (p. 119-209) contains papers on the papal visit in AD 1020 and the consecration of the St Stephan Church in Bamberg. Should you buy this book? Only if you like to have a complete set on your shelves. Whilst the first volume contains a lot of information and beautiful detailed pictures of the Imperial Vestments that are useful to us as embroiderers, this second volume is clearly only intended as a summary for the general public. If I had known what was the content of each volume exactely before buying, I would probably not have bought this second volume. This second volume can be ordered from the publisher Schnell & Steiner.

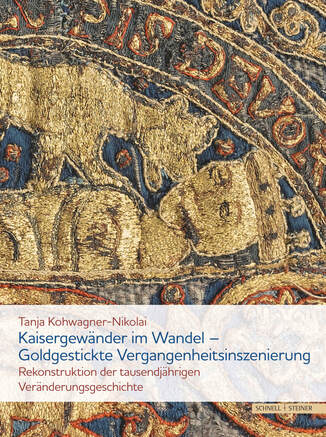

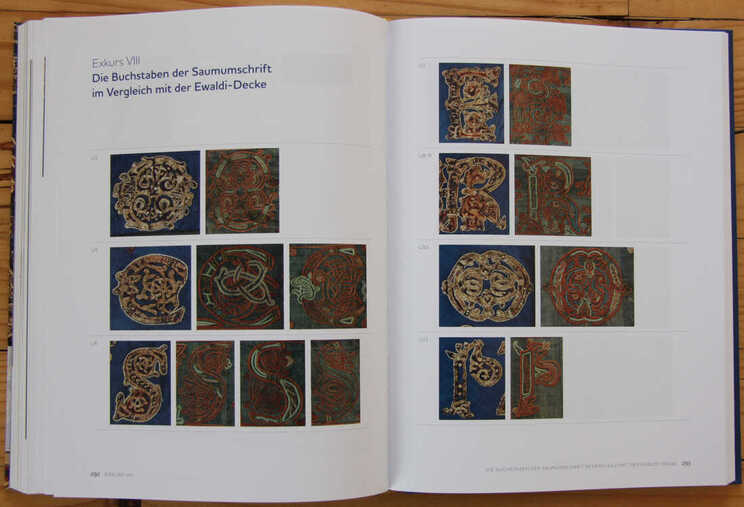

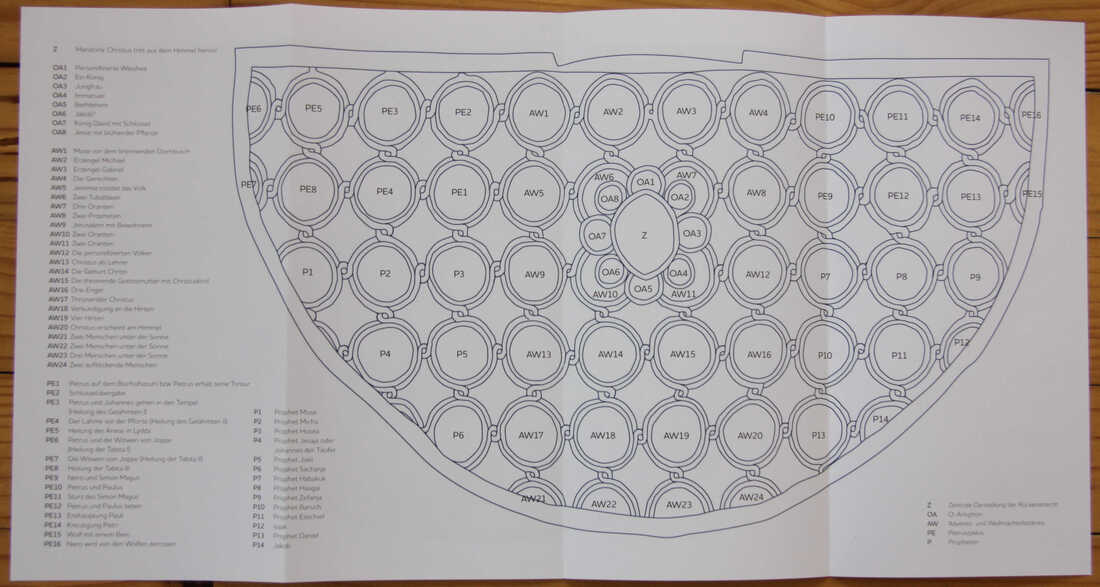

Jung, N. & H. Kempkens (eds), 2021. Die Bamberger Kaisergewänder unter der Lupe. Methoden und Ergebnisse der aktuellen Forschungen, Schnell & Steiner: Regensburg. By now, I have written a couple of blogs about the gold-embroidered garments held at the Diocesan Museum in Bamberg. These embroideries are about a thousand years old and are associated with Holy Roman Emperor Henry II and his wife Kunigund. For the past five years, the vestments were part of an interdisciplinary research project. The results are now being published in three volumes. Although these vestments are unique, with very few parallels elsewhere in the world, these volumes are unfortunately being published in German. Just like the Dutch thought it a brilliant idea to publish their unique collection of late-medieval vestments in Dutch in 2015 and the Italians cleverly published a monograph on the unique orphreys designed by Pollaiuolo in Italian in 2019. How about making it mandatory to publish in English for all scholars in the world? Enough of a rant. Let me review the first of the three volumes (the other two are not yet published). It is a beautiful book, even if you are condemned to only admiring the many detailed pictures. This first volume "Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung. Rekonstruktion der tausendjährigen Veränderungsgeschichte" (Changing imperial garments - staging of the past in goldembroidery. Reconstruction of a 1000-years of change) came out in 2020 and is written by Dr Tanja Kohwagner-Nikolai. The book is very well structured with a detailed chapter each for the six garments that make up the Kaisergewänder. Additional detailed information on a very specific aspect of a particular garment is published in an "Exkurs" or sub-chapter. There are a whopping 10 of these. There is also an introductory chapter and a concluding chapter. Tanja is an art historian who has specialised in epigraphy (the science of letters). This specialisation comes in handy as there are many embroidered texts on some of these garments. Using her expertise, Tanja found parallels in other textiles and manuscripts which meant that she could narrow down where a particular garment was likely made or designed or by whom. She also carefully studied all the available historical documents on these garments. Church accounts document the many instances when these garments were being repaired. Revealing who did the work (women were often involved) and how much it cost and how long it took. Luckily, Tanja also reveals a lot of the details a typical stitcher with an interest in goldwork embroidery wants to know. Goldthreads, fabric, silken embroidery threads and stitches are described in detail. And although there will be a separate volume dedicated to the subject, there is already a lot of information woven into the narrative of this volume. And then there are the many detailed close-up pictures of the embroidery. Quite a few have been taken through a high-resolution microscope. Four folded-up A3-ish maps of three of the garments are tucked in two pouches on the inside of the cover. These are absolutely brilliant. They show a picture of the garment with a simple outline drawing of the whole design and a description of each scene. This makes talking about a particular part of a garment so much easier. No negatives? Oh yes, it is written in German. And although I am a near-native speaker, I had to look up some words. Written German is somewhat different from spoken German. Scholarly written German is a whole lot different from spoken German. Additionally, when Latin is cited, it is not always translated. After all, Tanja writes for a scholarly German audience. Latin is mandatory for them (the fact that I hold a doctorate, but never had a Latin lesson in my life, is quite incomprehensible to German colleagues).

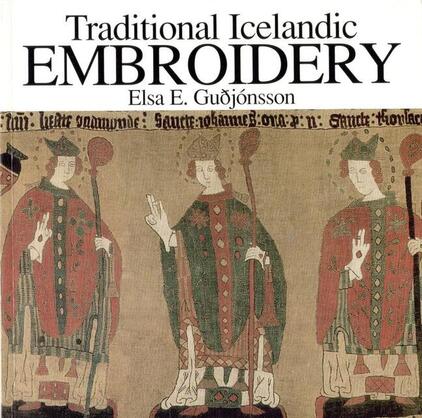

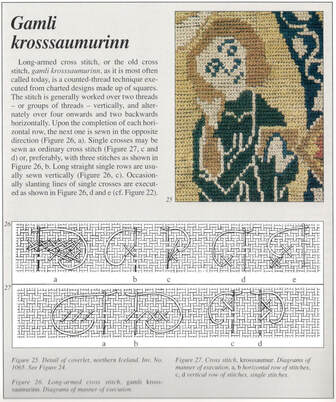

Personally, I do not like the way sources are cited. Only the last name of the author without the year of publishing is stated. This bugs me. I like to know who wrote what when. This shows me in an instant if a particular scholar could have known the source cited. As I know Tanja personally, I do know that she can embroider and do other forms of needlework and sewing. However, I feel that the research project would have benefited greatly by adding professional goldwork embroiderers to the team. Replicating small parts of each of these garments with materials that come close to the originals would probably greatly enhance our understanding of the embroidery. Being able to repair or conserve historical needlework is not the same as being able to make a replica. It would also have given us a better idea of what the original embroidery once looked like. After all, the colourful silken threads that were used to couch down the near-pure goldthreads have faded considerably or are completely gone. This means that the intricate couching patterns are nearly invisible. These patterns would have dominated the fresh embroidery and would have given it a completely different look. Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2020. Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszeb´nierung. Rekonstruktion der tausendjährigen Veränderungsgeschichte. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg. The book is available directly from the publisher and costs €69 + shipping. Today I am going to review a lovely little book most of you would probably never have come across: Traditional Icelandic Embroidery by Elsa E. Gudjonsson written in 2006. In only 96 pages, Elsa gives an overview of Icelandic embroidery made during the past 500 years in English (!). Being a rather barren island where almost everything needs to be imported, the embroidery is of a special nature too. Whilst mainland Europe uses silks both for the threads and for the fabrics, Icelanders used wool on wool or linen. Both for ecclesiastical embroidery and for embroidery on folk dress and household items. The use of metal threads is rare. The book consists of two parts: History & Techniques and 23 pages of original patterns. The later have all been transcribed as cross-stitch patterns with a key for DMC stranded cotton. The book describes several techniques which are characteristic of Icelandic embroidery: Refilsaumur (laid and couched work), Glitsaumur & Skakkaglit (straight darning and pattern darning), Gamli krosssaumurinn (long-armed cross-stitch), Augnsaumur (eyelets), Pellsaumur (Florentine stitch or bargello), Sprang (darned net and drawn thread work) and Blomstursaumur Skattering (floral embroidery). Each technique is explained with stitch diagrams and pictures of historical pieces. I was especially surprised to find whole embroideries worked in long-armed cross-stitch after AD 1550. They remind me of the much earlier embroidered vestments now in St. Paul im Lavanttal, Austria. Interestingly, the name "Gamli krosssaumurinn" means old cross-stitch. Krosssaumur is the modern Icelandic name for cross-stitch embroidery. As for Continental Europe, modern cross-stitch does not feature in medieval embroidery. Unfortunately, very little is known about Icelandic embroidery in the Middle Ages due to a lack of surviving pieces and an absence in the written sources. Especially the latter is remarkable as there are plenty of sources describing textiles. However, the few sources that exist indicate that women were the embroiderers. There are no instances of men being named as embroiderers. Especially upper-class women and nuns were involved in the production of high-end embroideries for the church. This tradition continued after Iceland became Lutheran in AD 1550. One particularly saucy embroidery story involves Helga Sigurdardottir. She was the wife (yup, they did things a little differently in Iceland) of the last Catholic bishop of the see of Holar, Jon Arason. In AD 1526 they drew up a contract in which was stipulated that Helga would make embroideries for the church of Holar as long as she was able. She became a set income per year for her service. Helga's work must have been outstanding as she is named in a poem of AD 1594 as one of the most skilful needlework women of her day. Helga probably trained up her grand-daughter Pora Tumasdottir who became a famous church needlework woman herself. And what happened to bishop Jon? He was killed by the troops of the Danish king in AD 1550 when he revolted and refused to accept the reformation of his church. Where to find this book? I bought my copy directly from the National Museum of Iceland for about €23 + shipping. They also have a second book that might interest you: a facsimile of Icelandic pattern books from the 17th-, 18th- and 19th-centuries. However, that one is quite pricey at €180. Pictures of several pages of these original pattern books are included in the embroidery book by Elsa. I know that these books can probably be had from Amazon and the like. But please consider ordering from the National Museum directly. Museums are hit hard by the pandemic due to closure or greatly reduced numbers of visitors due to the absence of tourists. The Museum shipped my book immediately and it was here within two weeks. The ordering process is easy with a credit card and completely in English.

P.S. Virginia Sullivan won last week's giveaway and has been contacted. The cross-stitch charts are on their way to her. A thank you to all who participated! The German publishing house Schnell & Steiner has a number of interesting books on medieval vestments in their programme. Discounts are applying until the 23rd of December. So if you are thinking of adding books to your library, this is a good time! However, it is a German publishing house and the books are in German. And one, in particular, might look like a good idea, but maybe isn't. That's the one I am going to review here. Don't get me wrong, it is a great book! But as it is the result of a multi-disciplinary conference with theologians, philosophers, art-historians, Germanists, archaeologists, anthropologists and philologists, it isn't for everyone. Paramente in Bewegung (paraments in movement) is an edited volume of 17 papers published in 2019. These papers have one thing in common: they are all theoretical. Only one author started out with a practical apprenticeship in tailoring. All others are academics through and through and they write for an academic audience with German as their native language. Although I am fluent in German, I had to look up many words in the theological and philosophical papers. And even then I was often left wondering what the author was saying ... However, a couple of papers helped me to better understand the context the embroidery I admire so much functioned in. So, from the point of view of an academic researcher into medieval embroidery, this book is a must-have on your shelves.

Jürgen Bärsch writes about the liturgy and the church building in the late medieval period. Even those who have attended a modern Catholic mass will soon realise that late medieval mass was quite different. Taking communion was rare and instead the elevation of the host was the pinnacle of each mass. Believers would hasten through the church building to attend multiple elevations as masses were not only held at the main altar but also at the many altars belonging to wealthy families, brotherhoods or guilds in the aisles. And as Stefanie Seeberg explains in her paper, the paraments used during these sacred performances all stood in relation to each other and to the building they were functioning in. Similar scenes were repeated on the vestments as seen in the architectural decoration of the church building (wall paintings, leaded windows, sculpture). Most people couldn't read nor understand the Latin the priest was using. But by constantly seeing the same images, the Christian message was understood by all. Additionally, an interesting observation was made. As the priest becomes part of the whole scene, he as a person is no longer important. However, as we nowadays see these splendid vestments in isolation, we often draw the opposite conclusion: the wearer must have stood out. For the two papers on the theological and historical explanation of vestments (Rudolf Suntrup and Dina Bijelic), there is a better alternative available in English: Clothing the Clergy by Maureen Miller. I've reviewed this book a while ago. The papers by Britta-Juliane Kruse and Tanja Kohwagner-Nikolai explore paraments in the reformed convents of Lower Saxony. They are commonly called Heideklöster as they are located on the Lüneburg Heath. They escaped the dissolution but changed from Catholicism to Lutheranism. They are famous for the large medieval embroidered tapestries stitched entirely in Klosterstich (Bayeux stitch). The papers attest to the high level of education in these convents. The daughters of the nobility were able to decode the complex stories on the paraments. They had read the classical literature and knew how these motives related to the Christian faith. Studying the actual embroideries also reveals that the ladies themselves stitched and designed these tapestries. And they were proud of their excellent work: later pieces are signed. Stefan Michel and Evelin Wetter write interesting papers on the perception and use of vestments after the Reformation. Whilst the more radical Calvinists objected to the continued use of the Catholic vestments, Luther actually saw nothing amiss with the practice. As long as people did not worship the depictions. The special clothing was only there to support the sacredness of the mass. We now often think that all depictions were radically removed from every church that became reformed. This is true for most churches in the Netherlands, Scotland and Switzerland as they followed the teachings of Calvin. However, large tracts of the Germanic lands followed the teachings of Luther. And they often continued using, repairing and replacing their splendid medieval vestments. Imke Lüders' paper on the use of images of skulls and bones on burial vestments makes for an interesting read too. And Klaus Raschzok's paper on the re-discovery of paraments in the Lutheran churches shows that this movement was particularly influenced by the 19th-century Gothic revival in the Catholic church. This movement had started in England with the influential publication by August Welby Northmore Pugin: "Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume". You can download this publication for free and marvel at the beautifully hand-coloured designs in the second half. En passant, the paper goes into the question of who should make fitting paraments for the reformed church. One movement wanted to go the professional route by educating deaconesses both in theological design and in the needle arts. The other movement emphasised that each godly woman should help make paraments for the church instead of using her needlework skills to frivolously decorate her own home ... Don't you love it when men discuss how we should use our skills? I hope the above book review helps you to decide if this book is for you or not. Very soon, three volumes will be published on the medieval gold-embroidered vestments from Bamberg by the same publishing house. As soon as they arrive, I will review these too. They look very promising! Literature Röper, U. & H. J. Scheuer (eds), 2019. Paramente in Bewegung. Bildwelten liturgischer Textilien (12. bis 21. Jahrhundert), Schnell & Steiner: Regensburg. ISBN: 978-3-7954-3338-3. P.S. In an attempt to do my bit to break the data monopoly of Google and Facebook, I have transferred all my videos to the video platform Vimeo. Please give me a follow! And in order to have more time for embroidery and researching embroidery, I have decided to close my Instagram and Pinterest accounts. No wonder I have suddenly time to read whole books and a newspaper :). |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed