|

Last month, we looked at some early 15th century embroidery from Venice, Italy. You can read about it here: Cope of Pope Gregory XII, further early 15th century embroidery from Venice and a tutorial. This week, we will look at a Venetian piece from the second half of the 15th century. It has some lovely embroidery techniques that would work well for modern goldwork embroidery. And the embroidery background is a bit unusual as well. Instead of using a diaper pattern, it is made of floral motives stitched directly on coloured silk. Let's have a look! I saw the above chasuble at the exhibition in Castello del Buonconsiglio in 2019. The exhibition presented an overview of medieval goldwork embroidery made in Italy; complemented by those pieces that were obtained by trade from Northern Europe. The chasuble is kept, and still being worn once a year!, at the parish church of Azzone, near Bergamo, in the Scalve Valley. The valley came under Venetian rule in 1427 and this probably explains why this piece of Venetian embroidery can be found in Azzone. The chasuble has an embroidered orphrey cross on the front and an embroidered orphrey column on the back. As the figures on the front cannot be identified, the exhibition showed the back. Here we see John the Evangelist at the top, followed by a male martyr with a palm branch and architectural model (According to the literature it is a church. However, it looks more like a castle to me.) and the figure at the bottom is Saint Barbara with her tower. Saint Barbara is the patron saint of miners. The Scalve Valley was famous for its iron ore mines. The embroidery is executed on a layer of silk backed with linen for the background and a layer of linen for the figures. The heads were embroidered separately. The finished orphrey column was stiffened with cardboard. The orphreys measure about 33 x 12 cm. The embroidery is a rather simple, yet very effective, affair. The figures stand on a floor made with laid shaded silk and couched down with a trellis. By having the lighter colour at the front and the darkest colour at the back, the embroiderer created a sense of depth. The undergarment of the martyr is stitched in a similar way. This time, the laid silk is couched down horizontally. The cloak consists of horizontally laid pairs of gold thread which are couched down with white silk. Folds are accentuated with couched coloured silk. The heads are stitched in split stitch.

The treatment of the background behind the figures is quite special. The coloured silken background is part of the design. It is covered with the obligatory arch under which the saint stands. The background is further filled in with tendrils and floral elements. These are made by couching down a pair of gold threads and filling in some elements with shaded satin stitch. The frame around the orphrey consists of a very simple padded basket weave over two padding threads (over three is probably more common). All in all, the embroidery techniques used (laid work instead of brick stitching for the undergarments, simple monochrome couching for the cloaks instead of or nue, embroidered coloured silk for the background instead of a diaper pattern, etc.) are simple and far more speedy to execute than or nue, brick stitching and diaper couching. This likely means that these embroideries were not as expensive as the ones we investigated last month. Literature Prá, Laura Dal; Carmignani, Marina; Peri, Paolo (Eds.) (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Trento: Castello del Buonconsiglio.

1 Comment

When I was in Trento, Italy, a couple of weeks ago, I did also visit the Diocesan Museum. It houses an important and impressive collection of ecclesiastical art. The building itself is the old Praetorian Palace where the Prince-Bishops of Trento lived. From one of the rooms you can actually look down into the Cathedral. Quite a spectacular sight! Although the museum houses many exquisite works of art, my main concern where the embroidered vestments. There are a few very fine examples of medieval goldwork embroidery on display. The most important pieces consist of a chasuble cross and five orphreys from a dalmatic (vestment worn by the deacon). The sublime silk and goldwork embroidery was executed between 1390 and 1400 in Bohemia. Now part of the Czech Republic, but then an important and independent kingdom ruled by the House of Luxembourg. Charles IV (1316-1378) became king of Bohemia and also Holy Roman Emperor in 1346. He is the founder of the Charles University in Prague, the first one in Central-Europe. This was Bohemia's Golden Age and it is thus no wonder that there were embroidery artists of this skill working within its borders. The chasuble cross and the orphreys are part of the vestments made for Prince-Bishop Georg von Liechtenstein (reign 1390-1419). He was born in Moravia. Now part of the Czech Republic and bordering Bohemia. Since AD 955 it formed a union with Bohemia. It seems that Georg patronised local Bohemian/Moravian embroidery artists when he moved to Trento in AD 1390. But on the orphreys he had them tell a typical Tridentine story: the vita of Saint Vigilius of Trent. The patron saint and first bishop of Trento. I can see why he used his fellow countrymen to make these works of art: the style is rather distinctive. With friendly round faces and bodies. Once you pay attention, you can spot a Bohemian embroidery before reading the museum caption. Perhaps, similarly today, Czech and especially Czechlowakian postal stamps have a very distinctive style. Also on display was a chasuble made of white linen and embroidered with silks. I've written an ebook on these particular vestments made in the 17th century in Tyrol. This particular piece isn't made with great skill :). But the patterns and the colours of the flowers are identical to the flowers on the chasuble from the Diocesan Museum of Brixen. However, the Museum in Trento dates the piece much later: first half of the 19th century. But also admits that not much is known about its provenance.

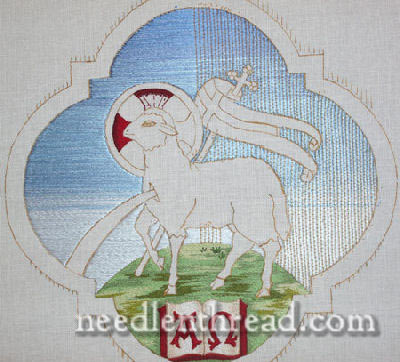

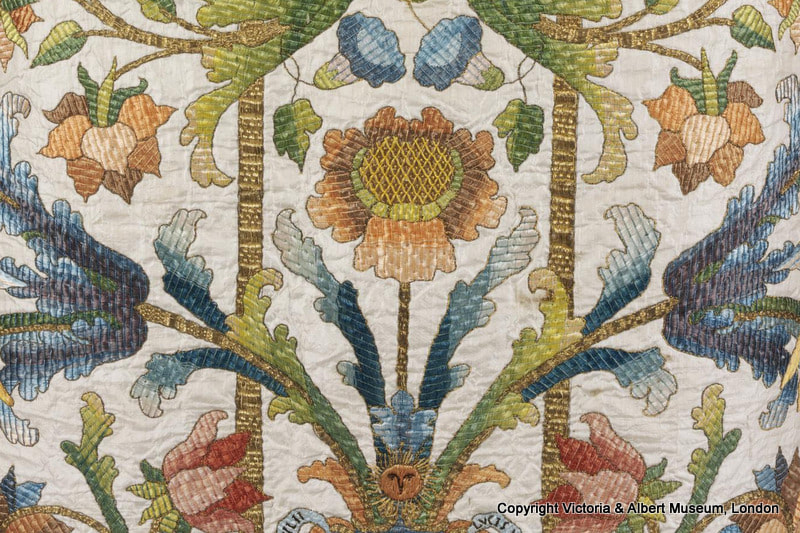

When Trento does not happen to be next door to where you live, the museum published two excellent books (in Italian I am afraid) on its textile collection: Devoti, D., D. Digilio & D. Primerano, 1999. Vesti liturgiche e frammenti tessili nella raccolta del Museo Diocesano Tridentino, no ISBN. Officially out of print, but available second-hand when you ask Google :). Primerano, D. 2011. Una storia a ricamo. La ricomposizione di un raro ciclo boemo di fine Trencento, ISBN 978-88-97372-02-8. Ask Google :). When I visited the Diözesanmuseum Brixen in Italy last year, I was captivated by one chasuble particularly. It wasn't particularly old or made with extraordinary skill. But to me, it just screamed: FUN to embroider. And I had seen this particular technique before on an unfinished sampler in the collection of the Wemyss School of Needlework in Scotland. The particular pieces were made with fibrant coloured silks in a simple couching technique (Bayeux Stitch) and seem to originally date to the 17th century. Then my internet search began. I proved not to be the first to write about 'Italian couching'. In 2007, Mary Corbet wrote an article about 'Italian Stitching' on her blog Needle 'n Thread. Through the related articles, I found the book Mary had originally consulted: Church Embroidery and Church Vestments by Lucy MacKrille written in 1939. You can download it for free here. If you like goldwork embroidery and embroiderying with silk, you'll love it! And what does it say on 'Italian Stitch'?: Italian stitch in which stout floss is used for a foundation is the most beautiful of stitches. The floss is stretched across the surface from end to end of the design, care being taken not to twist a fibre, so that when the surface is covered it will be as smooth as satin. The finest gold thread is then laid across the silk in lines one-eight of an inch apart and couched evenly. The beauty of this stitch depends on the glossy smoothness of the floss, the straightness of the lines of gold, and the evenness of the bricking or couching stitches (MacKrille, 1939 p. 27-28). Hmm, not my 'Italian Couching' after all. The examples I saw in the Museums in Northern Italy were al couched with matching silks, not with gold thread. Could it be that 'Italian Stitch' was actually an Anglo-American invention and not of true Italian origin? Let's check with Pauline Johnstone writing on Italian Embroidery in 'Needlework: an illustrated history' edited by Harriet Bridgeman and Elizabeth Drury from 1978. There it says: An alternative technique was laid and couched work in colored silks, crossed and held down by spaced lines of gold thread. ... Many vestments of this type are attributed to Napels, where the Kings of Napels and the Two Sicilies held a wealthy and lucurious court (Plate 45). (Johnstone, 1978, p. 143). So, what does Plate 45 show? Not much in a book from 1978. It is in colour, but a whole chasuble at only 10,2x9,3 cm, doesn't tell a whole lot. Luckily, this particular chasuble is held at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. And they have a digital archive! You can find the entry for the chasuble featured in the 1978 book here. Lo and behold! This is indeed the needlework technique I have seen in a few pieces in Northern Italy and the unfinished sampler in Scotland. And as you can see, the laid silk is couched with a matching silk thread. Not with a gold thread.

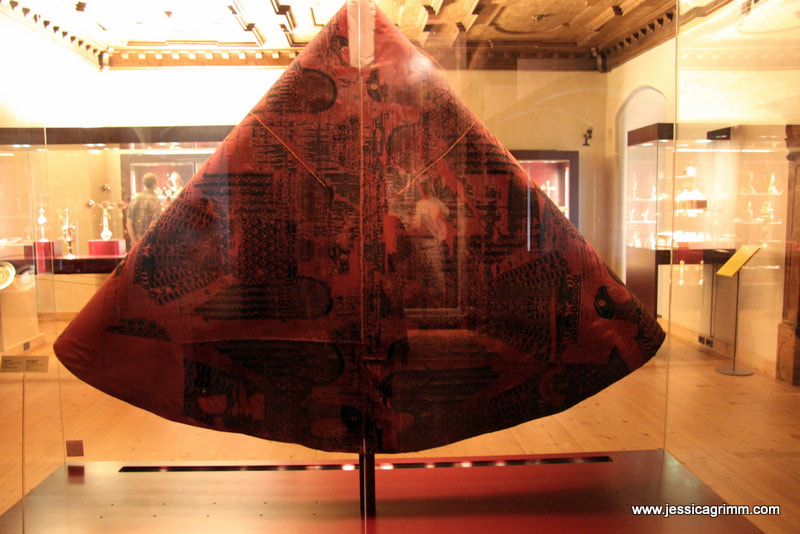

So, can you see what happened here? An authority on 'modern-day' church embroidery from America, but who studied embroidery in England, wrote on a couching technique with silks and gold thread she had learned and used in 1939. Later researchers on Italian needlework presumed this was a historical technique used in 17th century Italy. They had a bad photograph from the V&A collection and a brief description naming floss silks and silver-gilt thread. Combining the two into a Bayeux stitch with silks and gold thread. Now don't get me wrong. The Itialian Stitch embroidery executed by both Lucy MacKrille and Mary Corbet looks absolutely stunning. But it does not seem to have been a historical needlework technique in use in 17th century Italy. However, if you have come across a historical piece made in Italy which does use gold thread as the couching, please do let me know! In the mean time, I'll keep my eyes peeled for more pieces in this fascinating technique. As part of the 'Samt und Seide 1000-1914. Eine Reise durch das Historische Tirol' (Velvet and Silk 1000-1914. A trip through historical Tyrol) exhibitions organised by the European Textile Academy, I and my husband visited Brixen/Bressanone and Klausen/Chiusa. We were completely blown away with the high quality embroidered textiles we saw and are already planning two more trips. Unfortunately, for most of you, Northern Italy is a bit further away than our three-hour drive. However, if you are ever in the neighbourhood, do visit the two museums I am going to introduce you to further below! They are absolutely worth it. And do take a print-out of this blog with you if you are not proficient in either German or Italian, as English is not the lingua franca in Northern Italy... First up is the Diözesanmuseum in Brixen. It houses the cathedral treasure of the former Diocese of Brixen. A large part of their permanent exhibition is devoted to textiles. The oldest being from around 1000 AD! However, this museum follows the modern concept of presenting historical art as art. Descriptions of the individual objects are very meagre and only available in German and Italian. There is nothing wrong with appreciating pieces as they are and enjoying the display in front of you. However, I would have liked to have the option of getting more information. Preferably as laminated information available in the display room AND a decent catalogue to take home. After all, I like to go to museums to learn and broaden my knowledge. That said, the sheer amount of high-quality exhibition pieces gets you into textile heaven in no time. My favourite pieces were the oldest pieces. Just the idea that the Eagle Chasuble (Adlerkasel) dates to 1000 AD. It was made at the court of the Emperor of Byzantium and given to Bishop Albuin of Brixen. It was probably one of the first silken vestments which arrived in this part of Europe. Due to its great antiquity and pretty good conservational status, it is one of the most important textiles of Europe. Another highlight were these pontifical gloves dating to the 15th century. They feature email medallions from 11th century Byzantium, showing again how important this imperial city once was in medieval Christian Europe. And aren't these tiny beads made of freshwater pearls to die for? I definitely want a pair! The museum also has several 15th. century orphreys on display. These heavily embroidered gold- and silk pieces were once appliqued onto a chasuble. Look at those couched diaper patterns forming a pretty background for the holy figures. Just unbelievable that someone cut through them to make them fit onto a new vestment... Then there were 17th. century chasubles with colourful silk and goldwork embroidery. I particularly liked the one with the small and detailed flowers. Look at the iris worked in long-and-short stitch and then further embellished with tiny fly-stitches to give the speckled impression often seen on an iris. The other chasuble shows a particular style of silken laid-work with couching stitches I first encountered on an Italian piece in the Wemyss School of Needlework Archive. I think it is very colourful and pretty. Great sources of inspiration! The next museum we visited was the Stadtmuseum in Klausen/Chiusa. They have by far the better (=higher quality embroidery) textile collection and it is displayed in such a way that you can get very close to the pieces and the lighting is excellent. Unfortunately, I wasn't allowed to take pictures. I didn't know I wasn't allowed to take any, so I can at least show you an antependium, or altar cover, from the Loreto treasure. And I (and the very friendly museum wardens) hope that it will whet your appetite so that you plan a visit too. And that you will help spread the word that this museum has a textile collection of high importance. As they are a tiny museum with an equally tiny budget, they need our help. So please show them some love. But first, let me tell you a little bit more about what is called the Loreto Treasure. Maria Anna of Neuburg became queen of Spain, Sicily, Naples and Sardinia when she married king Charles II of Spain in 1690. She brought with her her confessor Pater Gabriel Pontifeser born in Klausen. He was a trusted and loyal advisor and she pledged to build him a monastery in his hometown of Klausen. The house he was born in was turned into a Loreto chapel. Queen Maria Anna, her husband and the Spanish nobility gave beautiful religious objects to the chapel. The Loreto treasure was born. Permanently on display in the museum are several highly decorated altar covers. Apart from the one displayed above, which was probably stitched in Sicily, there is a further piece stitched in wool on linen and a silk- and goldwork piece in the Ottoman-style. Interestingly with the piece I was able to photograph, the main part with its flowers, birds and butterflies is stitched with long-and-short stitch. However, the border shows the same laidwork technique as seen before on the chasuble in the Diözesanmuseum Brixen. Besides silk and gold threads, the piece is adorned with red coral beads. This piece is truly to die for! It is very seldom that you encounter embroidery of such high quality that has kept so well. Other spectacular pieces were several chasubles with the same high-quality silk and goldwork embroidery. If you are ever near, this is a museum not to be missed! I for my part, will be back to study these pieces in greater detail.

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed