|

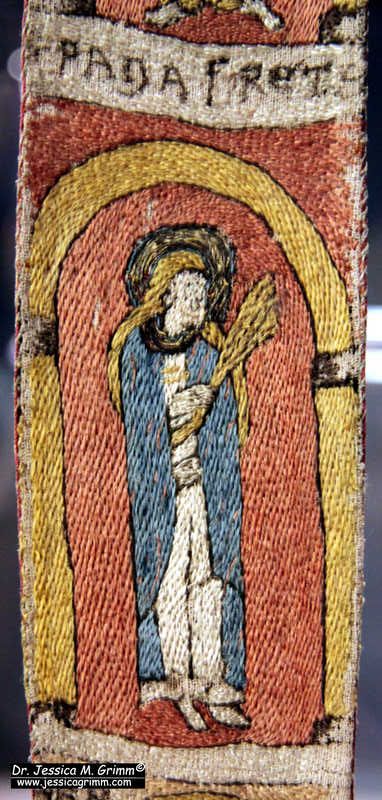

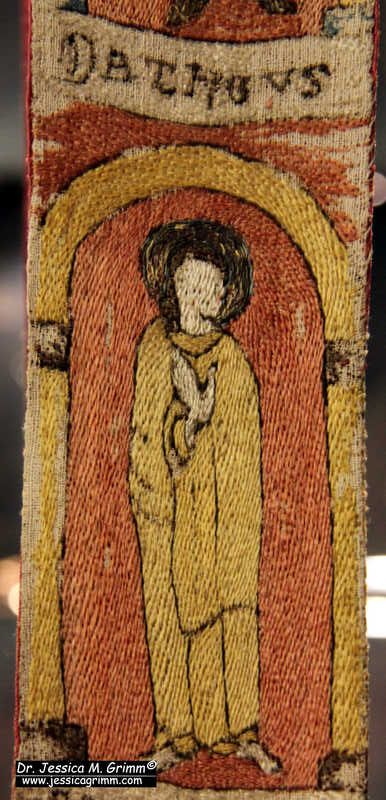

Today, we are going to revisit the Uta-chasuble in Marienberg Abbey in Southern Tyrol (Italy). I originally visited the small museum in 2017, but I was never able to lay my hands on a publication. Last week, however, I found the only publication on this extraordinary piece in my favourite second-hand bookstore on the internet. So here comes my updated blog post on the Uta-chasuble. During my second trip to Northern Italy, I visited the Benedictine Abbey of Marienberg in Mals. Their museum is also part of the exhibition 'Samt und Seide 1000-1914: Eine Reise durch das historische Tirol' curated by the European Textile Academy (you can read about my first trip here). This museum houses one of the crown jewels of medieval embroidery in Europe: the Uta chasuble stitched around 1160 AD. To give you an idea of its importance, the oldest pieces in the famous 'Opus Anglicanum' exhibition in the Victoria & Albert museum in 2016/2017 were a seal bag from 1100-40 AD and several embroidered fragments from 1150-1200 AD. The oldest embroidered complete chasuble in the exhibition was the Clare Chasuble from 1272-94 AD! Similarly, the oldest embroidered chasubles in the exhibition 'Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden' in the Catharijneconvent in Utrecht in the Netherlands in 2015 is dated to the late 15th century. High time I introduced you to the Uta-Chasuble! The above pictures show you the Uta-Chasuble from the front and the back. In the right picture, you also see the matching stole. The embroidery shows a tree of life spread all over the chasuble. Inside the top part of the forked cross, you see Jesus inside the mandorla flanked by two angels and several stars and crowns. Jesus is seated on a throne, holding a book in his left hand and raising his right hand in a blessing. This is the so-called Christ Pantocrator. On the back of the chasuble, we see the Agnus Dei flanked by the symbols of the evangelists. The evangelists are portrayed as winged figures on which only the heads differ (Matthew man, Mark lion, Luke ox and John eagle). Originally, the chasuble would have been a bell chasuble. At some point, probably in the 14th or 15th-century, the sides were cut for easier movement. Here you see a detail of the back of the chasuble, just inside the forked cross, showing two of the winged evangelists. You can see every silken stitch (they are between 2-7 mm long). In the literature, the stitch is described as alternating rows of stem stitch. However, I think the stitch is brick stitch. This was a stitch particularly popular in the German-speaking areas. You can also see the faint lines of the original drawing. It looks like the design drawing was done free-hand. There is also some couching with metal thread left on the winged evangelists (single metal thread couched with red silk). Two different types of gold thread were used in the embroidery: Membrane gold with a white linen core and gilt silver foil wrapped around a yellow silken core. These parts of the embroidery are so well preserved because a forked cross was appliqued onto the embroidery. This forked cross was made by cutting up a precious piece of lampas silk. This silk came from Persia and dates to the 10th or 11th-century and is thus much older than the chasuble. The pattern on the purple silk consists of pairs of parrots. These birds are framed with circles filled with Kufic script and small animals. Now, why would you cover parts of your embroidery with pieces of silk? Once the silk was taken off the chasuble it revealed that they covered the seams between the different parts of the chasuble. It turns out that the chasuble consists of seven separate pieces. And they were clearly embroidered by different people. When they stitched the embroidered pieces together to form the chasuble, the difference in stitch length and direction was far too noticeable. That's why the seams were covered with the strips of silk. Here you see one of the angels flanking Jesus inside the mandorla. Pattern couching is present on Jesus' clothing. Instead of the now common bricking pattern, the couching pattern forms a slanting line. This pattern can be seen more often in medieval goldwork embroidery. The colour palette for the silk embroidery on the fine linen background (43-58 ct) is quite restricted: red, yellow, blue and brown. Accompanying the chasuble is a matching stola showing saints. In the picture on the left, you see St. Panafreta, one of the 11.000 virgins following St. Ursula to her martyrdom in Cologne. On the right, you see St. Datheus. He was archbishop of Milan and opened the first home for abandoned children in 787 AD.

Oral history claims that the chasuble was stitched by Uta von Tarasp and her ladies. Uta and her husband Ulrich were the beneficiaries of Marienberg Abbey. But who drew the pattern? Was it the same person who painted the frescoes in the Abbey Crypt? And where were the precious embroidery threads coming from? A large quantity of consistently spun and dyed silk thread as well as metal threads. Apparently, the silk threads came from Sicily. Did Uta and her ladies work the chasuble on large embroidery frames in a room in Tarasp castle? How was the work divided amongst the women? How fine were their needles? Did they have artificial lighting or could they only work in daylight? Would there be music played or a book read aloud when they were working? Let me know what you think! Literature Hörmann-Weingartner, M., 2004. Die Uta-Kasel in Kloster Marienberg, in: Stampfer, H. (Ed.), Romanische Wandmalerei im Alpenraum. Veröffentlichungen des Südtiroler Kulturinstitutes 4. Südtiroler Kulturinstitut, Bozen, pp. 129–148.

13 Comments

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed