|

As Germany stumbles out of the lockdown we have been in since December, I and my husband took the opportunity to visit the exhibition of the "Kaisergewänder" in the Diocesan Museum Bamberg. Although I visited this museum before, this time the latest research results on the goldwork embroidery were on display. Luckily, my husband was so kind to come on a 660 km round trip with me (promising him cake always works!). If you would like to visit this exhibition yourself, you will have to do so before the end of the month or before the rate of infections rises above the threshold again. You will need to make an appointment through the museum website and fill out a form. So, what new things did we see? First of all, I was really impressed with the amount of information now available for each vestment on display. The original captions were VERY short and that was a major disappointment on my first visit. Secondly, there was a whole room devoted to the "raw data" of the research project. This will probably all become available in the three monographs I have on pre-order. Looking at the tracings and other study results, many of my own assumptions were confirmed. And I learned so much more about these goldwork embroideries that you just cannot see with the naked eye or learn from the pictures I took and enlarged on my computer. A rather interesting piece on display was a copy of the Regensburger rationale. This is a special vestment awarded by the pope to some bishops and was modelled on the ephod of the Jewish high-priest. It is hardly being worn today. The original was stitched in AD 1314-1325, probably in Regensburg. The copy was made for Bishop Franz Wilhelm von Wartenberg (AD 1649-1661) and is now held at the Bayrische Nationalmuseum in Munich (T 178). The copy was likely made to be used by the bishop to spare the original. As you can see, the stitching on the original rationale is made with much finer goldthreads than that on the copy. And now the stalking :). As always, I take many pictures, when allowed. At some point, two women sneaked up to me as they were curious to know who this lady-with-a-Canon-stuck-to-her-face is. It turned out that I knew one of them, Dr Ludmila Kvapilová, scientific associate of the museum (recognising people with a facemask is an art I have not yet mastered). The other lady turned out to be the new head of the museum: Carola Schmidt. Carola trained as a technical weaver before studying art history. The three of us had a lovely conversation and at some point, I mentioned that I had stitched a small sample based on the lettering seen on the Sternenmantel for the conference "Über Stoff und Stein" (you can find my blog on this reconstruction here). They asked if they could display the sample as part of the exhibition. Sure! So, today I mounted the sample and send it to them. This way they can also use it as a teaching aid. I am looking forward to staying in touch with them and to sharing my expertise.

If you would like to learn to professionally mount your finished embroidery, you can find downloadable instructions in either English or German in my webshop.

10 Comments

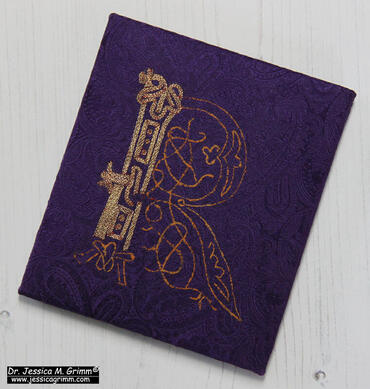

This is the last article in the series accompanying the conference 'Über Stoff und Stein' in Munich. The other three articles can be found here: part I, part II and part III. For my last goldwork embroidery sample, I choose a letter from the Sternenmantel of Holy Roman Emperor Henry II held at Bamberg. You can read about my visit to the museum where it is housed here. As one of the conference organisers, Dr. Tanja Kohwagner-Nikolai, is also head of the research team for the embroideries held at the Diocesan Museum in Bamberg, I was able to ask very specific questions about the embroidery. I was even given a high-resolution picture of the particular letter (for obvious copyright reasons, I can't publish that picture here). Join me in my musings on recreating part of a very elaborate 'R' from a stunning piece of embroidery that's a 1000-years old. The original goldwork embroidery was worked on a dark purple samite. This is a specific twill-type weave for silk fabric which was popular in the Middle Ages. I only once had a small piece in my hand which was found during an archaeological excavation in the medieval parts of Emden in northern Germany. Samite is hard to get hold of nowadays. Czech-based company Sartor recreates historical samites for the re-enactment scene. Fortunately for my purse, they don't have a dark purple one in stock. Instead, I had a look in my fabric stash and came up with a paisley patterned silk damask. Next up was transferring the pattern. The drawing of the 'R' is very intricate and can only be transferred onto the fabric once simplified. I made a pricking of the simplified drawing and used white pounce powder for the transfer. The white dots were then connected with watered-down watercolour Raw Siena (see video above). As the drawing is so intricate, I did my utmost best to keep the paint lines as fine as possible. NB: From the high-resolution picture I could tell that the letter is 9.5 cm tall. As I worked with my original pictures and some crude maths, my copy is about a centimetre taller. The Sternenmantel has undergone major alterations since it was first stitched around AD 1020. The first major re-make took place in the 15th century when the gold embroideries were cut out from the old mantle and appliqued onto the blue silk damask we see today. The thick red and white embroidered lines along the edges of the lettering date to this re-make. The original lettering looked indeed very different. The goldthread used for the lettering is a kind of very fine passing thread. The strips of gold foil wrapped around the silk core are less than half a millimetre wide and have a near pure gold content. In comparison, most ordinary gilt goldthreads used today have a gold content of 0.3% -2%. There are about 46 goldthreads per centimetre and this makes each goldthread around 0.21 mm. This is comparable to a modern-day Stech vergoldet CS 70/80 or a smooth passing #3. The goldthread is couched down as a single thread with red silk yarn. I've used DeVere Yarns Carmine #666. There is no regular couching pattern. Although the high-resolution picture is much better than my original pictures, I still am unable to tell if the tails of the goldthreads are plunged and tied back on the reverse of the fabric or if the ends are simply cut off and secured with an extra couching stitch. It is highly likely that the answers lie beneath the thick white and red contour lines which were added in the 15th century when the goldwork was taken off the original mantle (or mantles) and appliqued onto this 'new' one. I was also told by the head of the research team that the restoration in the 20th century now makes it impossible to inspect the reverse of the embroidery. This is very unfortunate indeed, but also shows the great strides made in textile conservation since then. In my reconstruction, I did not plunge my ends in accordance with the later Gothic embroideries from the Low Countries where there was no plunging either. I know that this is a long stretch both in time and area. However, the goldthread used is so pure that it would have been far too costly to waste any of it on the back. During the conference, I had a lovely discussion with both Tanja and Dr. Holger Kempkens on who made the Sternenmantel and the other magnificent goldwork embroideries held at the Diocesan Museum Bamberg. We readily agreed that it was not noblewomen or nuns, but men in professional workshops. Probably travelling with the highly mobile imperial court. And with connections to both the Western world and the Islamic world. Modern-day professional commercial goldwork embroidery is often executed by men (for instance the cover for the Kaaba in Mecca). The first mentions in the historical records of women doing goldwork embroidery either as creators or repairers are from the 17th century in this part of the world (the situation is different in England). And then there is the embroidery itself. The couching on the lettering is done in a very specific way. Although the couching stitches are placed randomly, the goldthread is by no means laid randomly. The embroiderer made sure that this very precious thread was laid down in the most economic way with as little starts and stops as possible. This is easy to do on the straight parts, but far less easy on the 'knotty' bits. Although I stared long and hard at the picture, I found out halfway through the actual stitching that I had it wrong. In comparison, my husband needed very little time to figure out the correct 'path'. Now please don't get me wrong or accuse me of sexism, but there are things in life MOST men can do better than women and vice versa. Not ALL men or ALL women. And this is not to say that there aren't women out there that can do this job perfectly. But I get the feeling that this particular embroidery job suits men better than women. Please don't hate me. Demonstrating historical goldwork embroidery techniques to the conference delegates was very enjoyable. They were tremendously interested and had lots of questions. It is so important to get both 'head' people and 'hands' people in the same room talking to one another. Tanja's idea of doing just that for this conference was brilliant and I certainly hope that it will get copied like mad by others. Literature

Baumgärtel-Fleischmann, R. 1983. Diözesanmuseum Bamberg ausgewählte Kunstwerke, Bayerische Verlagsanstalt Bamberg. ISBN 3-87052-380-8. Grimm, J.M., 2021. A hands-on approach - Epigraphy in medieval textile art, in: Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., Päffgen, B., Steininger, C. (Eds.), Über Stoff und Stein. Knotenpunkte von Textilkunst und Epigraphik. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, pp. 141–147. Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., S. Ruß & U. Drewello, 2016. Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung, Restauro 5, pp. 48-53. Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2014. O Decus Europae Cesar Heinrice? Die Saumumschrift des sogennanten Bamberger Sternenmantels Kaiser Heinrichs II., Archiv für Diplomatik, Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde 60, pp. 135-1646. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! Happy New Year to you all! My 2020 started with a 630 km round-trip to Bamberg. The diocesan museum houses some of the finest medieval goldwork embroideries in Europe. These exquisite pieces are a staggering 1000-years old! I was able to take some good pictures, which I am going to share with you here. Unfortunately, there was virtually no information available in the museum so I can't really tell you much about the pieces. However, I've ordered some literature and will do a further post with those details when the papers arrive. Probably the most famous piece held at the museum is the so-called "Sternenmantel Kaiser Heinrich II des Heiligen" (star mantle of Saint emperor Henry II). It was used as a cope or pluviale and measures 297 cm by 154 cm. The mantle shows Christological depictions, astrological signs and 14 roundels with busts of saints and many Latin inscriptions explaining what is depicted. Unfortunately, the gold embroidery was re-applied to the blue Italian silk damask we see today in 1503. The original design got mixed up and not all writing makes sense. Some scholars argue that in fact two mantles were made into one. The original background fabric was a dark-purple silk samite. Traces can still be seen on the inside of the different design elements. When the pieces were transferred onto the new blue damask, the edges were covered with a thick white strand of silk couched down with a thinner strand of white silk. To have an even better attachment, some of the design lines on the inside were covered with split or chain stitches using red silk. The original gold embroidery uses VERY fine passing thread and white, red, blue and green silk for the couching stitches. It looked to me that the passing thread has been couched as a single thread, rather than in pairs. Traditionally, this mantle is dated to AD 1010-1020 and its place of origin as Regensburg with a ?. The mantle is seen, based on the embroidered inscriptions, as a gift from Melus of Bari (died 1020 in Bamberg) when he sought the support of Emperor Henry II for his revolt against the Byzantine Empire. It is, therefore, more logical that the mantle was made in Southern Italy. The second famous mantle held at the diocesan museum in Bamberg is that of Saint Kunigunde, wife of emperor Henry II. This cope measures 286 cm by 162,5 cm and shows biblical scenes, a.o. related to Christ saviour and to the lives of the patrons of Bamberg Cathedral: St. Peter and St. Paul. Lettering around each roundel explains the stitched scenes. This cope was likely a donation by empress Kunigunde to the cathedral and made around 1020 AD in Southern Germany. The original VERY fine goldwork embroidery was stitched on a background of blue silk twill. There are 56 parallel passing threads per centimetre (!!!) and this means that each passing thread (a strip of gold foil spun around a silk core, see my previous blog on the manufacture of gold threads) had a width of about 0.18 mm. In comparison: my finest passing thread (Stech 50/60 CS) has a width of 0.22 mm. Pretty mindblowing, don't you think?! For the figures, these parallel passing threads lay vertically and are couched down in several different patterns using white, red, light- and dark blue silks. Further details are stitched in stem stitch. The embroideries from this mantle have also been re-applied onto a new fabric in the 16th century. Why have these two pieces survived in such splendid condition? This is due to the fact that both copes or mantles were related to the emperor and his empress. Both were sanctified. Bamberg employed these famous saints for their own marketing purposes since the late Middle Ages. This is likely the reason why the pieces were re-applied and probably altered then. Quasi to strengthen the case of the link between Bamberg and these two saints. Currently, a four-year research project on these vestments runs until 30-09-2020. For the first time, the art historians are employing scientific techniques to determine the origins of the materials used in these exquisite goldwork embroideries. We can thus look forward to a volume of papers being published on the subject in the coming years! Literature Enzensberger, H., 2007. Bamberg und Apulien, in: Das Bistum Bamberg in der Welt des Mittelalters (=Bamberger interdisziplinäre Mittelalterstudien. Vorträge und Vorlesungen 1), C. & K. van Eickels (eds), p. 141–150. Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2014. O Decus Europae Cesar Heinrice? Die Saumumschrift des sogenannten Bamberger Sternenmantels Kaiser Heinrichs II, Archiv für Diplomatik, Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde 60/1, p. 135–164. Schuette, M. & Müller-Christensen, S., 1963. Das Stickereiwerk. Wasmuth. No ISBN. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤!

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed