|

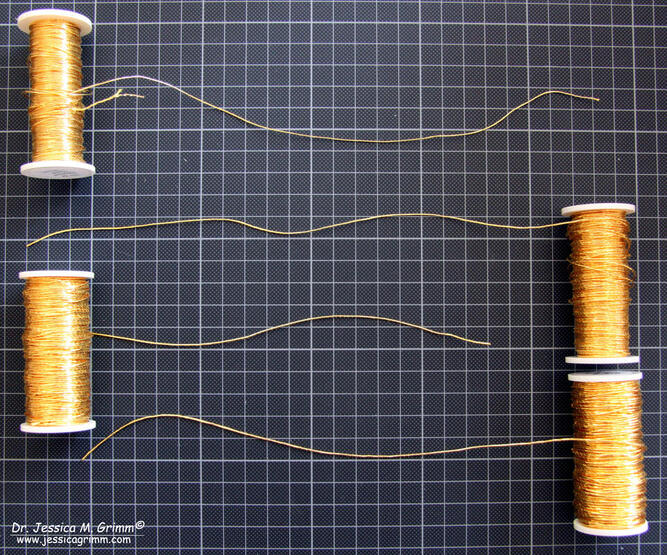

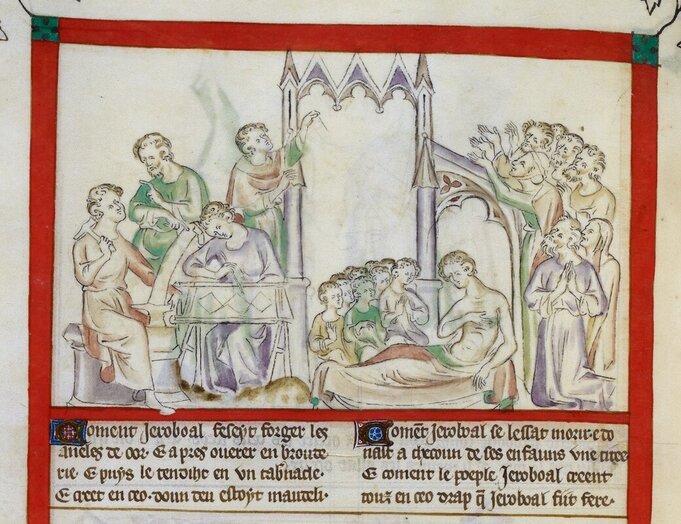

Nowadays we have a plethora of different gold threads at our disposal. Or better: metal threads as they are available in a wide array of colours too. However, it all started much, much humbler thousands of years ago. Yep, that's how long these beauties have been around. The oldest mention of gold threads is in the bible (Exodus 39, 3): "They hammered the gold into thin plates and cut them into threads in order to work it into the blue, purple and scarlet yarn and the fine linen crafted by the skilled artisan." Personally, I think a link between the eruption of the volcano on ancient Thera and the story of Exodus is very plausible. New C-14 dating evidence showed that this eruption took place around 1613 BC +/- 13 years. Bear in mind that the book of Exodus existed as oral tradition for many generations before it was finally written down. However, it could mean that the manufacture of gold threads is at least nearly 4000 years old. What did these earliest gold threads look like? Well, if we read scripture carefully, it suggests to me that they looked a lot like our modern plate. Thin strips of flat metal thread. On the other hand, the fact that they are "worked into the blue, purple and scarlet yarn" sounds a bit like it is being used as blending filament. Now modern-day blending filament is a super-thin polyester. Certainly not what the ancient Hebrews had at their disposal. Their thread must have been stiffer, heavier and thicker. But it might just be that they used it in a similar way as modern embroiderers use blending filament. Or they used the thin strips of metal just like the embroiderers in Turkey. They take a large flat needle and use lengths of plate IN the needle. Not like the way I was thought to use plate at the Royal School of Needlework where we couched it down. A disadvantage of used hammered precious metals as a base for your gold threads is that they are very expensive. Furthermore, when you work them into the garment, that garment becomes quite heavy. To overcome the first problem, gilt threads were introduced. This means that you use a more base metal such as silver or copper and you adhere a very thin layer of gold to it. This reduces the cost. But you are still left with the weight issue. In comes the invention of hammering the metal into even tinner sheets, cutting them into strips and adhering these strips onto animal gut or plant material such as mulberry paper. The combined material is then wrapped around a yarn core by means of spinning. These threads would have been comparable to today's Japanese Threads. When and where were these new metal threads invented? Unfortunately, the exact origin and time are unknown, but a pure gold strip likely wound around a fibrous core (not survived as it was a cremation) has been found in a Roman grave of a young woman in Cadiz, Spain. The tiny dimensions of the gold strip are mind-boggling: 0.2 mm wide and only 3.6 microns thick. There is a second method for producing metal threads: wire drawing. By passing a strip of metal through a progressivly smaller series of holes, very fine metal wire could be obtained. These were probably first used in jewellery production, but archaeological finds show that they were also used in textile production in China from the 2nd century BC and in the port of trade Birka (Sweden) from the 9/10th century. Some of these threads consist of tightly wound wires around a textile core. Although some researchers suggest that these wires were actually imported from the East (Byzantium) it is noteworthy that these kinds of wires have been known to the Sami people. However, they use pewter and not silver or gold. I wrote a blog article on their type of embroidery. These threads look like very fine pearl purl, but with a fibrous core. They are still produced today and can be obtained online from Swedish webshops. Gilded silver threads began to appear in the 9th century, but might be older. The oldest type consists of hammered sheets of silver covered with a thin layer of gold. When strips are cut from these sheets, they are gilded on only one side. These strips were then spun around a fibrous core. This type of gold thread is known as or de Milan. Were they invented in Milan or simply traded from Milan into the rest of Europe? These threads further developed in the 16th century as gilded drawn silver threads were hammered flat and spun around a fibrous core. These threads are all-over golden. These drawn threads have the huge advantage that they are much longer than the strips from the sheets and thus reduce the number of joints whilst spinning. This is in essence a passing thread. And then there is yet another method to produce a gold thread with a fibrous core: membrane gold. This is where animal tissue is gilded and then cut into strips which are then spun around a fibrous core. This method was likely invented in the 11th century and was both a much cheaper way to produce gold threads and it reduced the weight considerably. These threads were hugely popular and used in great quantities. These threads are commonly called Cypriot gold. However, new research by David Jacoby suggests that this is a misnomer. Furthermore, historical documents suggest that this type of thread was not at all cheap. Jacoby pushes for further research into the compositions of the alloys of the surviving gold threads as well as the identification of their cores and animal tissues to identify their origins. This would indeed make for exciting research and answer many questions regarding the how, where and when. If you are interested in the topic, do click the links for the Jacoby and Katzani papers as they make for interesting and detailed reading. They also provide lots of further papers in their references. Sources:

Friedrich W. L., et al., (2006): Santorini eruption radiocarbon dated to 1627–1600 BC., Science 312, p. 548–548. Jacoby, D., (2014): Cypriot Gold Thread in Late Medieval Silk Weaving and Embroidery. In: S. B. Edgington and H. J. Nicholson (eds), Deeds Done Beyond the Sea: Essays on William of Tyre, Cyprus and the gate Military Orders, p. 101-114. Karatzani, A., (2014): Metal thread: the historical development. Keynote lecture at the conference "Traditional Textile Craft - An Intangible Cultural Heritage?", The Jordan Museum, Amman. Stern, D.H., (1998): Complete Jewish Bible. Jewish New Testament Publications.

9 Comments

When I was in Trento, Italy, a couple of weeks ago, I did also visit the Diocesan Museum. It houses an important and impressive collection of ecclesiastical art. The building itself is the old Praetorian Palace where the Prince-Bishops of Trento lived. From one of the rooms you can actually look down into the Cathedral. Quite a spectacular sight! Although the museum houses many exquisite works of art, my main concern where the embroidered vestments. There are a few very fine examples of medieval goldwork embroidery on display. The most important pieces consist of a chasuble cross and five orphreys from a dalmatic (vestment worn by the deacon). The sublime silk and goldwork embroidery was executed between 1390 and 1400 in Bohemia. Now part of the Czech Republic, but then an important and independent kingdom ruled by the House of Luxembourg. Charles IV (1316-1378) became king of Bohemia and also Holy Roman Emperor in 1346. He is the founder of the Charles University in Prague, the first one in Central-Europe. This was Bohemia's Golden Age and it is thus no wonder that there were embroidery artists of this skill working within its borders. The chasuble cross and the orphreys are part of the vestments made for Prince-Bishop Georg von Liechtenstein (reign 1390-1419). He was born in Moravia. Now part of the Czech Republic and bordering Bohemia. Since AD 955 it formed a union with Bohemia. It seems that Georg patronised local Bohemian/Moravian embroidery artists when he moved to Trento in AD 1390. But on the orphreys he had them tell a typical Tridentine story: the vita of Saint Vigilius of Trent. The patron saint and first bishop of Trento. I can see why he used his fellow countrymen to make these works of art: the style is rather distinctive. With friendly round faces and bodies. Once you pay attention, you can spot a Bohemian embroidery before reading the museum caption. Perhaps, similarly today, Czech and especially Czechlowakian postal stamps have a very distinctive style. Also on display was a chasuble made of white linen and embroidered with silks. I've written an ebook on these particular vestments made in the 17th century in Tyrol. This particular piece isn't made with great skill :). But the patterns and the colours of the flowers are identical to the flowers on the chasuble from the Diocesan Museum of Brixen. However, the Museum in Trento dates the piece much later: first half of the 19th century. But also admits that not much is known about its provenance.

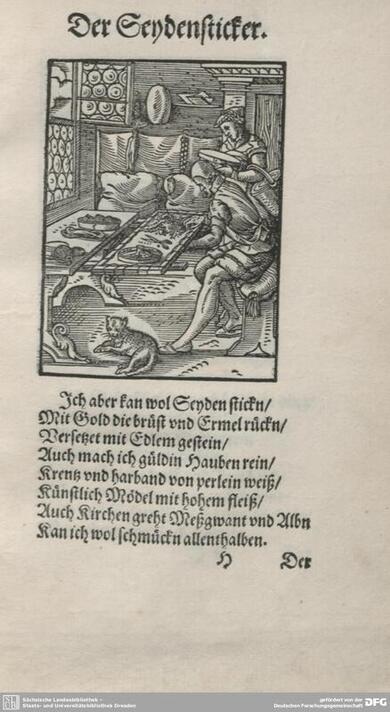

When Trento does not happen to be next door to where you live, the museum published two excellent books (in Italian I am afraid) on its textile collection: Devoti, D., D. Digilio & D. Primerano, 1999. Vesti liturgiche e frammenti tessili nella raccolta del Museo Diocesano Tridentino, no ISBN. Officially out of print, but available second-hand when you ask Google :). Primerano, D. 2011. Una storia a ricamo. La ricomposizione di un raro ciclo boemo di fine Trencento, ISBN 978-88-97372-02-8. Ask Google :). Some of you will know that I don't have a tv. Instead, I watch interesting documentaries (and highly necessary series like 'The Great British Bake Off`) directly on my laptop. One of my favourite channels is 'Arte' a French-German co-production. During this weekend's browse, I found a five-part series on the artisan production of fabric in Asia. Very beautiful and informative! The one on India zooms in on an embroidery atelier in Mumbai directed by the Italian professional embroiderer Maximiliano Modesti. He employs 600 embroiderers. All male, 98% muslim. Women do embroider, but not in a professional setting. This made me wonder how things were done in the 15th and 16th centuries in the Low Countries? After all, my favourite style of goldwork embroidery that I use as a basis for my artwork was made during this time. Would master embroiderer Jacob van Malborch have employed me if I had also lived in Utrecht in the first quarter of the 16th century? Someone who has done extensive research during the '80s and '90s into the organisation of professional embroiderers during the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times in the Low Countries is Prof. Dr. Saskia de Bodt. She extended and corrected the earlier attempts of Dr. Beatrice Jansen executed some 40 years earlier. In more recent years, art historian Dr. Marike van Roon researched the Dutch embroidery ateliers active between 1830-1965 extensively. As far as I know, more recent research into the role and organisation of medieval embroiderers is not available for the Low Countries. Note: It seems that the above-named scholars started their careers researching embroidery, but soon gave up in favour of more 'real' art history like 19th-century paintings or ceramics. Even in research, embroidery seems to have an image problem ... After going through many written sources such as the financial records of churches and towns, baptism records, marriage registers and death records from the 15th- 17th century located in the Northern Netherlands, Saskia de Bodt concludes that the professional embroiderer was a man. Only the men, like Jacob van Malborch and many others, are named. If a woman does show up in the records it is not under her own name but only as huysvrou van (housewife of) followed by the name of the master embroiderer. However, women were not explicitly excluded from the guild either. On the contrary. When the embroiderers of Utrecht formed their own guild in 1610, the guild ordinance speaks of meestersschen (female masters). The guild of embroiderers in Leeuwarden probably only consisted of men as the ordinance only mentions meesters and inwoonderssonen (masters and sons of poorters). But in Dordrecht, the embroiderers split from the St. Luke guild in 1487 as a result of a feud between the women ...

So would master Jacob van Malborch have taken me on as an apprentice? Possibly. Would someone have written down my name? Certainly not in the Low Countries. Female embroiderers are known from the written sources in other European countries. So I could have learned the ropes with master Jacob and then, after fretting over not making it into the written record, emigrate to Cologne or over the seas to England. But that's stuff for a further blog post. Sources: Bodt, S.F.M. de, 1991. Borduurwerkers aan het werk voor de Utrechtse kapittel- en parochiekerken 1500-1580, Oud Holland 105, pp. 1-31. Bodt, S.F.M. de, 1987. De professionele borduurwerkers. In: S.F.M. de Bodt, M.L. Caron et al, Schilderen met gouddraad en zijde, Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht. Jansen, B., 1948. Laat Gotisch borduurwerk in Nederland, Boucher. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed