|

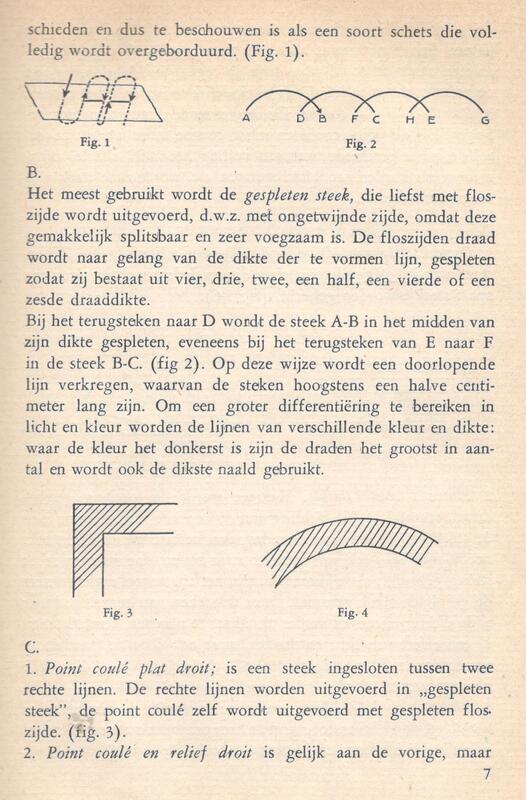

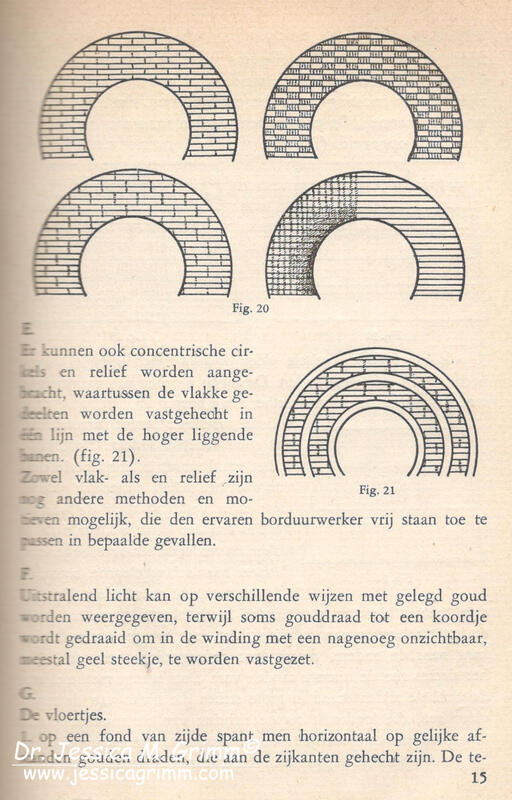

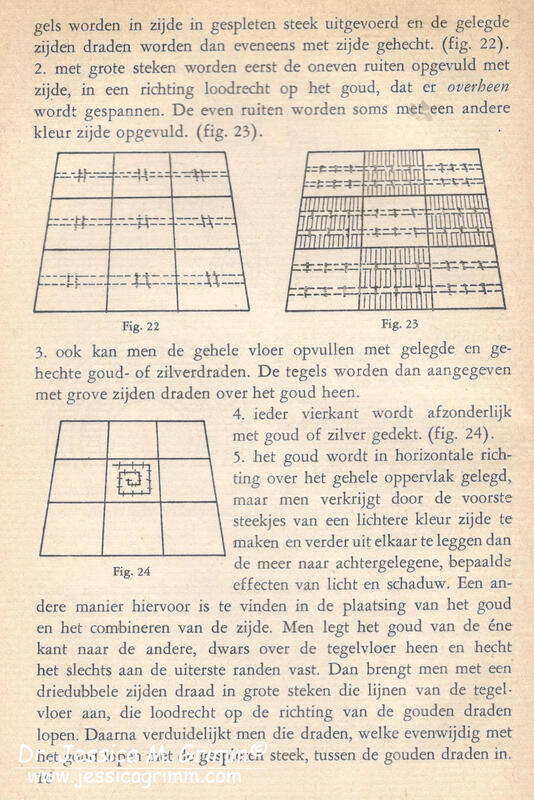

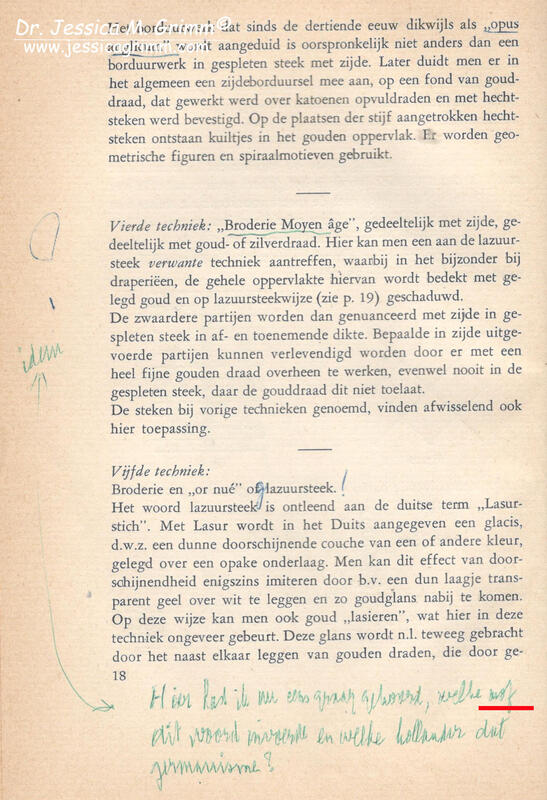

This might not come as a surprise to you: I love books on embroidery! Not only the so-called project books or books on a particular technique, but also museum catalogues and research papers. Whilst the first are usually promoted by and within the embroidery community, the later are a little harder to find. Second-hand bookshops are a good place to look for them. Since the topic is such a specific one, the people in the bookshop can often tell you in an instant if they carry some. Recently I rediscovered one such book in my extensive library. It is a Dutch doctoral thesis from 1948 written by Dr. Beatrice Jansen (1914-2008). The title of the thesis defended at the University of Utrecht is: Laat gotisch borduurwerk in Nederland (Late Gothic embroideries from the Netherlands). I bought the book years ago as I liked the technical and design drawings, but I had never actually read it ... Until now. And it actually is a gem! Let's explore together ... The first chapter concerns itself with the embroidery techniques used. Dr. Jansen was probably not an embroiderer, but certainly a true art-historian. Back in the late 1940s, art-historians used French and German sources for their research. Dr. Jansen copied the French names of embroidery techniques from 'La broderie du XIe siecle jusqu' a nos jours' from L. de Farcy printed in Paris, 1892. You can find an online digitised copy of the catalogue and all the black-and-white photographs here. Although these are truly lovely, I would rather have had a digital copy of the chapter with the embroidery techniques explained. It is quite difficult to understand what Dr. Jansen is talking about. The other source used is a German one: 'Künstlerische Entwicklung der Weberei und Stickerei' by M. Dreger written in 1904. This book can also be viewed online. However, this is only the text. They didn't digitize the plates ... Both books are still around and can be purchased from book dealers. However, they sell for hundreds (till thousands!) of euros. So I probably go to the library in Munich :). That said; when Dr. Jansen really dives into the embroidery seen on the Dutch liturgical vestments, she does present a lot of rather lovely technical drawings. And that's the true merit of this book. The next chapter is a lovely one too! Dr. Jansen presents all the historical sources concerning medieval embroiderers or acupictores as they were called. The female form, acupictrix was rare and only used as 'wife-of'. Indeed, professional embroidery was a male occupation and females only seemed to have contributed in the ateliers of their husbands (and maybe fathers). What is also interesting, the embroiderers did not have a guild of their own. They were usually part of the guild of the painters as they were seen as 'painters with thread'. The embroiderers did not only stitch new vestments; they are explicitly required to mend existing ones as well. And, this doesn't really come as a surprise: the job wasn't well paid and did not have the same standing as that of artisans working in the 'high arts' like painters and sculptures. Discrimination against textile art certainly has deep roots! The next two chapters try to divide the gothic vestments into a group made in the Northern Netherlands (roughly present-day Netherlands) and a Southern group (roughly present-day Belgium). These chapters are pure art-historian. Due to the fact that this book is so old, not all pieces talked about are represented by a black-and-white photograph in the catalogue. But lo-and-behold, I own a modern catalogue from the exhibition in the Catharijne Convent in 2015! So I wrote the modern catalogue number and, if applicable, the inventory number into the margins for quicker reference. Even before the publication of Dr. Jansen, art-historians have tried to name the artists who made the design for these vestments. Successful matches could be made with paintings, woodcuts and sculptures of which the names of the artists have survived. It becomes evident that prints circulated in the embroidery ateliers after which the embroidery was executed. Clients would have had very specific ideas about what they wanted on their vestments and in which style. Chapter V tries to further categorize the vestments by looking at the embroidered architecture. When you start looking at these vestments, you soon realize that certain elements of the architecture are very similar between different pieces. This chapter is richly illustrated with line drawings of all the different architectural styles found on the orphreys of the vestments. Chapter VI high-lights that these kind of embroideries were made at least a century earlier than the pieces that have survived in modern-day museum collections. The oldest painting depicting this type of embroidery is the Ghent Altarpiece made by Hubert and Jan van Eyck between 1427 and 1432. This chapter lists nearly 60 other paintings depicting this type of embroidery. The thesis concludes with a sammery in Dutch and English. I also found a rather embarrassing remark in the margin made by a previous owner. It reads 'Hier had ik nu eens graag gehoord, welke mof dit woord invoerde en welke hollander dit germanisme' (I would have loved to hear which mof (= Nazi) introduced this word and which Dutchman came up with this germanism). Remember, this book was published only three years after the end of the Second World War ...

Since this book was published so long ago, you can only find it in libraries (all over the world as it is a doctoral thesis!) or second-hand. Unfortunately, only more modern theses are available online from the University of Utrecht. And since the author died only 11 years ago, it will take another 59 years before the book can be digitised by me and put into the public domain :). I can probably just manage that before turning 100!

7 Comments

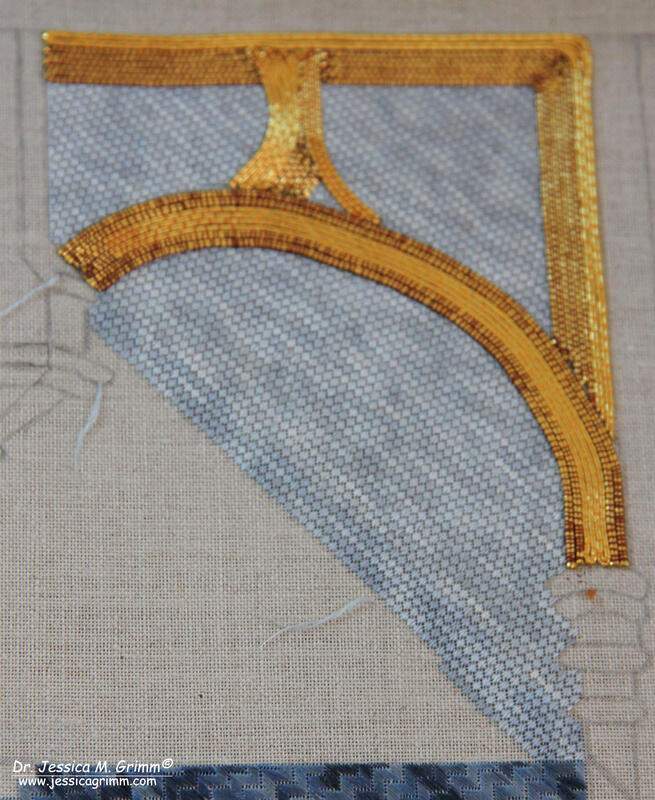

At the end of March, I started a new project: On the shores of St. Nick. I suddenly realised that I had not shared updates for a while. One of the reasons being: the piece is HUGE and progress thus rather slow. But I think you might find my musings interesting. Especially those of you who design their own pieces. This is how far I have come to date. As this is all done on 40ct natural linen by Zweigart, you can imagine the many, many hours of stitching to come this far :). Although I now know that it is unrealistic to get it finished before the start of my exhibition in August, I am rather pleased with how it is coming together! And since I have to man the exhibition myself, guess who will be stitching what :). This is a close-up of the migrant boat afloat on the mediterranean sea. The dark blue waves are stitched with House of Embroidery fine silk colour True Blue. The lighter waves use colour Forget me not M. Quite an apt name, don't you think? The stitch used is a common canvaswork stitch named Byzantine stitch. Another rather apt name since the migrants start out from modern-day Turkey. The boat itself is a rather simple affair. I used padded satin stitch for the light-grey parts. The silk used is a heavy (60-fold or 1200 denier), slightly twisted one from DeVere Yarns called Glacier for the padding. The satin stitches itself are stitched with Chinese flat silk. As are the darker parts and the life-jackets of the migrants. To achieve some distinction between the persons, I used different stitch directions and added some padding in a few cases. The migrant's heads are made up of a French knot made with the same thick silk in the colour acorn. For anybody not liking French knots: try one with this type of sligthly twisted silk. They turn out perfect. Promised! To close the little gaps between the canvas stitches of the sea and the satin stitches of the boat, I added a couched line using Glacier again and the accompanying very thin 6-fold (120 denier) silk. That's the great thing about the DeVere Yarns silks: you get them in a wide range of sizes and twists! In person, the boat has a very high-sheen and therefore a real 3D-effect. It does not come across well today in my pictures. We are preparing ourselves for a heatwave here in Bavaria and all my windows are completely covered in order to keep the heat out as best we can. And here is a close-up of the beach. I changed the size of the 'sand' pattern as it was too small. Typically, you would like the canvas filling stitches to be largest at the front (the beach in this case) and smaller in the background (the sky). This enhances the depth of the piece. The stitch used is oriental stitch and it is stitched with House of Embroidery fine silk (for the wet areas) and raw silk (not shiny) for everything else. The colour used is Mud. The letters of the word Peccatum (Sin) are stitched with lines of stem stitch all going in the same direction. To give the impression of the word being written in the sand, I will add French knots around the edges as soon as the background is fully stitched. And last but not least, a close-up of the sky and the goldwork frame. The filling stitch for the sky is condensed Scotch stitch and the thread used is House of Embroidery fine silk colour Forget me not. The variegated nature of this thread gives a really good impression of the sky, I think!

For the goldwork frame, I am using #8 and #12 Japanese Thread. This is only the first layer of gold threads. All the small gaps you see at the moment will be covered when the next layer is added. For the shading of the couching stitches, I am using three shades of very fine silk (6-fold or 120 denier) by DeVere yarns. The colours are: Allspice, Fox and Ray. I used to use split Chinese flat silk to do my shading and or nue on St. Laurence. However, the flat silk does not have a consistent thickness and this can cause difficulties when following the grain of the fabric. I now prefer using this very fine silk made by DeVere yarns as it does not have this problem. The National Silk Museum in Hangzhou had a small number of embroideries made by several ethnic minorities on display. After last week's book review on the textile traditions of one of these minorities, the Miao (Hmong), I thought it a good idea to share my pictures with you! First up is an embroidered apron worn by women of the Dong minority. The Dong are matrilinear people from the south of China. The embroidery on this apron consists of brightly coloured satin stitches (possibly over a cut paper template) and some applique. The pattern is made up of stylised flowers and the sun symbol (probably the swirls; Chinese explanations at museums are notoriously vague ...). Other parts of the apron consist of strips of wax-resist dyeing. Unfortunately, the only thing stated on this apron is that it was worn by an ethnic minority from Guizhou province. What I understand from the museum's description is that this is a single panel and that several of these embroidered panels would make up the actual apron. Do you see all these white buttonhole wheels? There are also chain stitches and knots. I think they used chain stitches to create the star shapes on the left and the maple leaves on the far right. Quite a clever and visually pleasing piece, I think! This panel was embroidered by the Ge people who also live in Guizhou province and who are officially considered to be a sub-group within the Miao. This piece mainly consists of outlines stitched with fine and very regular chain stitches. There is also some back stitch and some satin stitch visible. This piece of clothing (called 'braces' in the description) was also embroidered by the Ge people. It is again covered with very regular chain stitches and interspersed with satin stitches. The regularity of both pattern and stitching is absolutely stunning! The last piece on display was an embroidered shawl made by the Miao. The geometric pattern is based on an old song and represents flower beds. The stitching is entirely done in a form of long-armed cross-stitch. This is even a better close-up of the flower bed pattern. The movement created with the stitching is absolutely sublime! Keep staring at it and see how many different patterns you are able to see :).

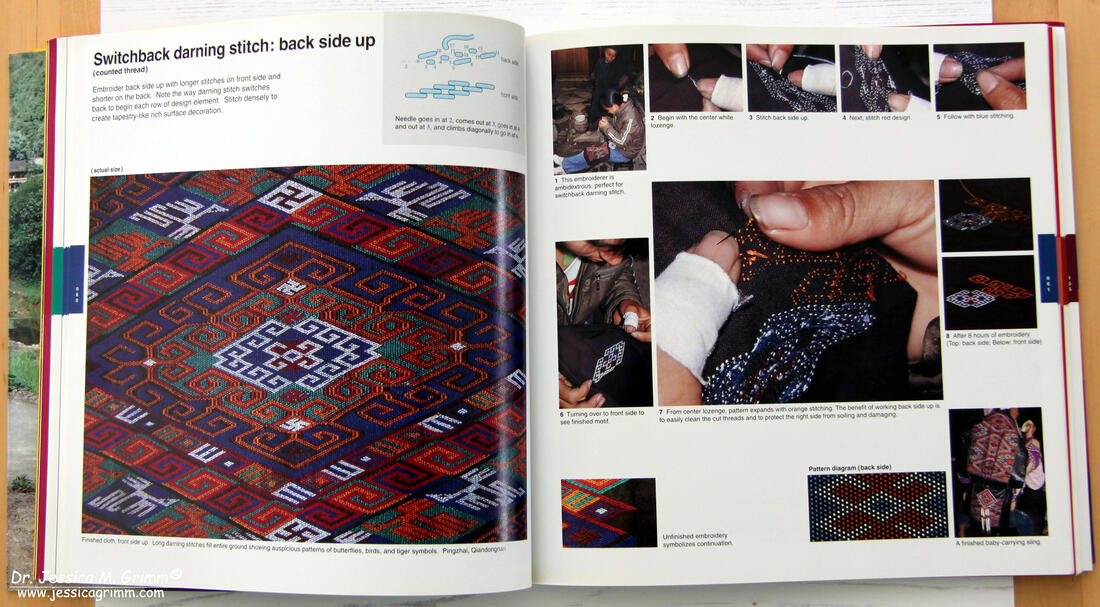

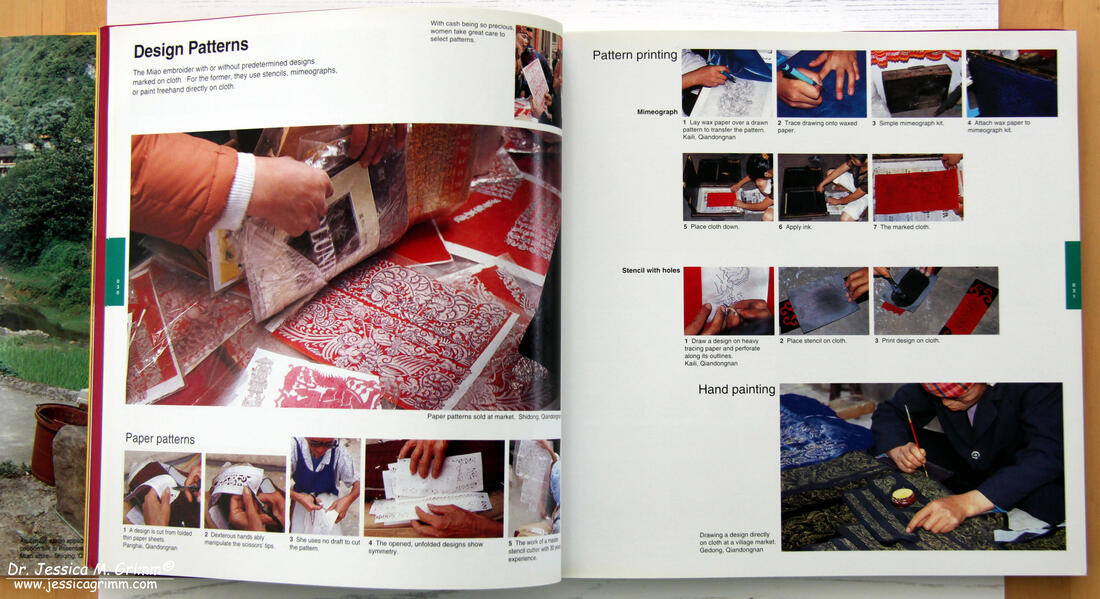

I was given this lovely book about ethnic embroidery from China by the lady who organised my teaching trip to China last year. This book on an interesting topic has a rather special and highly pleasing visual concept as well. Although it is not your classic project book, the step-by-step photographs and descriptions mean you can easily recreate particular stitches and patterns. Especially for those of you who are already adept at wielding a needle, there is a lot of 'new stuff' in this book which will make your hands itch. The book is written by Dr. Tomoko Torimaru, a Japanese woman who studied Chinese textiles at the University of Shanghai, China. She is the daughter and research-associate of her mother Dr. Sadae Torimaru. Together they have studied the textile traditions of the Miao and related ethnic groups for many decades. They are both well-known and respected textile researchers and deserve to be more widely known among Western embroiderers as well. Full details of the book: Torimaru, T., 2008: One Needle, One Thread: Miao (Hmong) embroidery and fabric piecework from Guizhou, China, University of Hawai'i Art Gallery, ISBN: 978-1-60702-173-5. And this is what a typical two-spread from the book looks like. Many detailed pictures with explanatory text. In this particular case, the darning stitch is worked from the back in order to protect the finished embroidery. One needs great skill to not make a mistake when carrying threads or otherwise the pattern on the front will show a mistake. There are several embroidery techniques detailed in the book where the embroideress works from the back to avoid soiling the finished embroidery. Throughout the book, you will learn about the myriad ways of pattern design and transfer. I am blown away by the fact that some paper-template cutters are so skilled that they do not need to make an outline drawing prior to cutting ... There are also many 'recipes' in the book for making starch and thread conditioner from local plants. You'll be amazed at how often the silk threads for embroidery are conditioned to behave during embroidery. I am always quite reluctant to use thread heaven or the like on my silk threads. I usually talk them into submission (with various degrees of success, I must admit). Another thing I was reminded by when reading the book from cover to cover, is how ingenious people are. We can be one heck of a clever naked ape! For the Miao, embroidering their folk costumes is typically done in between other tasks. When waiting or tending the family, for instance. There's often no ergonomic position to be had or good lighting. Slate frames or hoops for perfect tension? How about using your knees and thighs instead? And it is almost always an activity you'll share with other females. Knowledge transferred from mother to daughter. Underlining and taking pride in one's ethnic identity one peaceful stitch at a time!

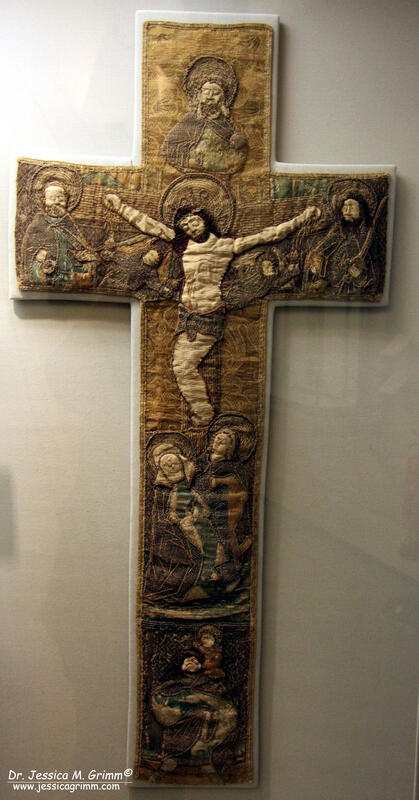

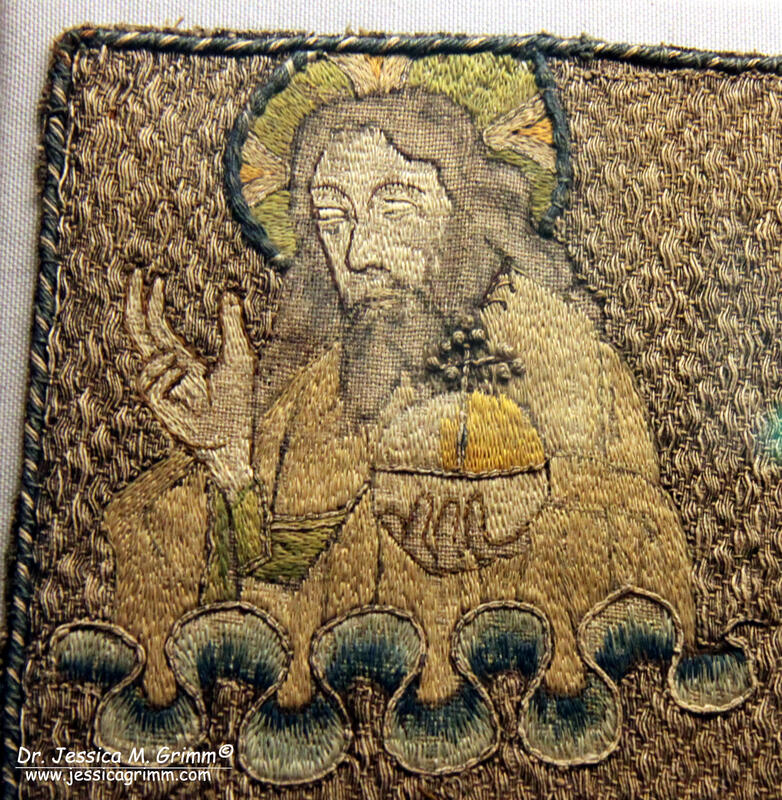

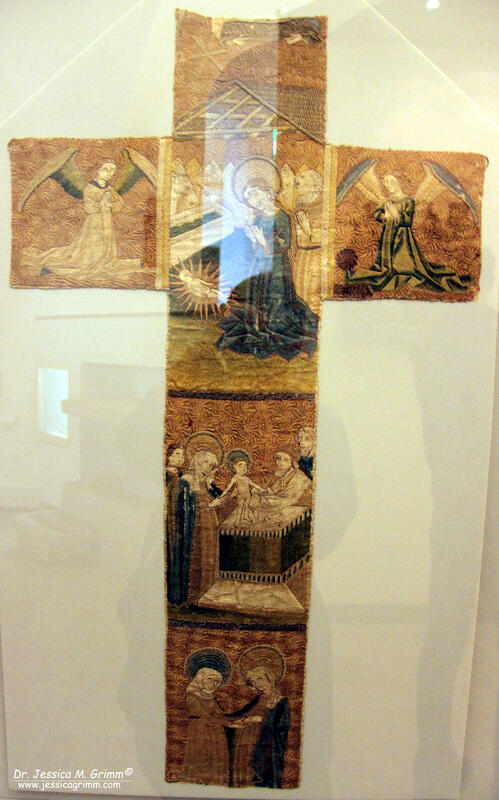

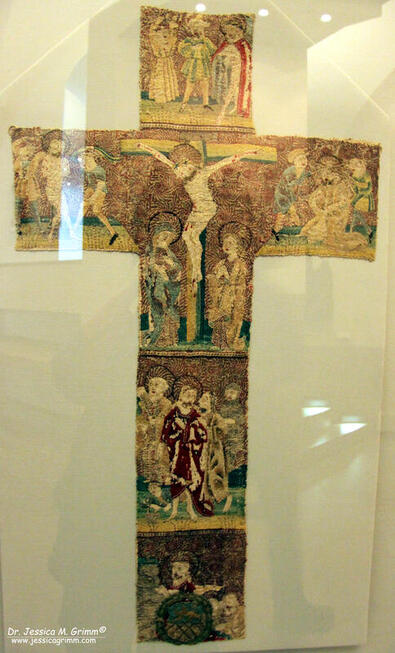

Last week, I showed you the vestments from the 17th and 18th century on display at the Dommuseum in Fulda. This week we will have a look at the medieval ones. Although the lighting was much better in this part of the exhibition, the glass of the showcases posed a huge problem when photographing the pieces. And to make matters worse, the warden revoked my permission to photograph. Nevertheless, I have a hand-full of nice pictures of very high-end goldwork and silk embroidery to share with you! First up are two pictures of an embroidered cross which would have adorned a chasuble. These embroideries were so precious, that they were mostly re-used on a new vestment when the old one was worn. In this case, the embroidery is a little special: it is raised embroidery. We often associate stumpwork embroidery with 17th-century England. In this case, however, the embroidery was done around 1500. The exact provenance was not stated, but these stumpwork embroideries were all made in the German-speaking parts of Europe. The most exquisite examples can be found in Mariazell, Austria. Here the figures stand about 3 cm proud of the background fabric! In the detail picture above, one can clearly see that the faces of both Peter and Jesus are padded. Jesus's ribcage is defined with a piece of string padding. The whole figure of Jesus seems to be somewhat padded. And the flesh-coloured fabric looks quite stiff and a bit like paper or vellum. And here we have two depictures of God from two different late-medieval chasuble crosses. Unfortunately, no further information was displayed for these two. Or maybe I forgot to take a picture ... I quite like these two. The clouds remind me somewhat of Chinese embroidery on the imperial Dragon Robes. Last up are these two. They are chasuble crosses embroidered around 1480. No provenance is given. These two caught my eye as the embroidery techniques used are quite different from the other vestments on display. No or nue here; the figures are stitched in silk using long-and-short stitch. In this detail shot, you can see what I mean. No or nue for the figures here. Instead, there is meticulous tapestry shading on the clothing (i.e. silk shading strict vertically instead of naturally). And the couching patterns for the goldwork threads in the background are so full of movement and quite different from the strict geometrical patterns seen in the late-medieval vestments from the Low Countries. I had a strange feeling that I had seen this before. And luckily for me, my mind sometimes does a good job :). Instead of needing to go through my thousands of pictures taken at museums, I knew at which museum I had seen this: the Diözesanmuseum Brixen, Italy. This late-15th-century (same date as the one from Fulda!) chasuble cross has a similar couched background. And most of the figures are stitched in tapestry shading rather than or nue (Mary being a notable exemption). So maybe the chasuble cross held at the Dommuseum Fulda has a more southern origin?

Being able to make these connections only works when I am allowed to take pictures. As lighting conditions or the way things are exhibited often do not permit studying the embroidery with the naked eye, my pictures are a great help. The camera is able to pick up details even when lighting is poor. I can zoom while taking a picture and again when looking at my pictures on the computer. Applying filters will tell me even more about the way things were made. It is therefore always very sad when the taking of pictures is not permitted. As long as you do not use flash (or use another source of light such as your phone!), you are not damaging the exhibits. And me taking pictures of the exhibits as is, has other benefits too. I don't need to make an official appointment for which museum staff needs to 'host' me (they have better things to do) and I don't need to handle the exhibits either. Some museums argue that by taking photographs and publishing them in a blog or on social media will mean fewer people will actually visit the museum. Really? I have the sneaking feeling that more people will visit a museum when they know what is on show. Especially museums with a wide range of exhibits of which textiles are only a small portion. The museum's website often does not specifically state that there are gorgeous embroideries on display (they are a somewhat neglected category, especially when in competition with bling made of precious metals) which might interest the curious embroiderer. And I know that several of my readers have visited museums which featured in my blogs. I have been guilty of doing the same. Maybe we should start mentioning these things to staff on duty when visiting a museum after reading a blog or seeing a picture on social media. What do you think? |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed