|

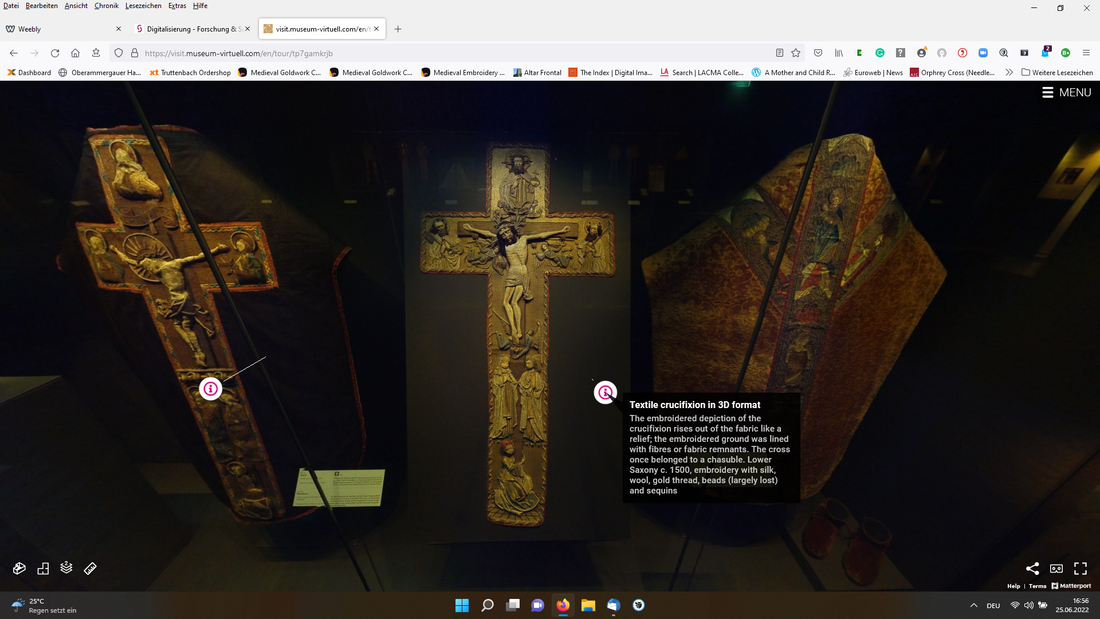

In a bit to compensate people for the high energy prices, Germany offers regional transport tickets for only nine Euros per month during June, July and August. Apparently to get commuters out of their cars and into public transport. Good luck to those of us living rurally. For example, my husband. He works in Ettal. That's only 18 km from where we live. He starts work at 9:30h. Public transport can either get him there at 7:20h or 9:50h. He ends work at 17:30h. Last travel option 17:05h. My husband would be perfectly willing to have a public transport commute of 45 minutes instead of the usual 20 by car. However, he is simply unable to take up the offer as there is no public transport available. On the upside: I use my ticket to do a bit of research travelling! Yes, it takes a long time to paste regional trains together to get from the South of Germany to the North, but it is practically free. Besides, there are only regional trains running when you go from the South to the East on many routes. Something that was never fixed since the wall came down. You also need to be flexible as the trains are very crowded and there is no guarantee that you can be transported. So, what did I visit? Three of the most important medieval and Renaissance textile collections in the world. We'll kick off with two of them: Domschatz Halbertstadt and St. Annen Museum Lübeck. My travels started off in Halberstadt. The cathedral treasury houses one of the most important cathedral treasures in Europe. It is probably also one of the museums with the largest permanent display of medieval textiles. Over 70 pieces, from luxurious patterned silks, to amazing goldwork embroidery to stunning whitework and huge tapestries, can be seen. There are only two major downsides: the level of lighting is so poor that you will have a hard time seeing the embroidery clearly. And secondly: you are not allowed to take pictures (which I doubt you can without flash anyway). Modern LED-lighting concepts for museums can allow for a better visitor experience but this costs money. Luckily, there is a beautiful publication (see literature list at the bottom of this post) which has beautiful colour pictures and detailed descriptions of about 60 pieces. It even contains many close-up pictures where you can literally see every stitch. There is also a full collection catalogue underway which will be published through the Abegg Stiftung. In my personal opinion, their publications are the gold standard when it comes to embroidered textiles. When you are interested in medieval embroidery, the Domschatz Museum should be on your 'to visit list'. You can easily spend several hours here. I'll recommend that you come prepared and have read the below-mentioned publication. This way you'll have so much more information as the museum captions are rather anecdotal. For those of you who cannot visit in person, the museum website has an excellent digital tour. Click on 'menu' at the top right and choose between DE or EN for language. Then click on the door opening. Depending on your internet connection and your device, be patient while the application loads. Click on 'floor selector' bottom left and choose 'floor 2'. The textile rooms are on either side of the main structure. Left for the whitework and the tapestries and right for the embroidered vestments. Enjoy! From Halberstadt, I travelled on to Lübeck in the North. That's almost 900 km from home :). The St Annen Museum is located in a former convent and also houses one of the most important textile church treasures in Europe. Due to the peculiarities of (recent) European history, Lübeck houses the treasury of St. Mary's church in Gdansk (formerly Danzig). For conservational reasons, only a tiny fraction is on display at a time (check the website to see which pieces). However, recently a complete collection catalogue was published (see literature list below). The texts are detailed, but could contain a bit more on the embroidery in most cases and not all pictures are as detailed as an embroiderer wishes. Nevertheless, it is a must-have addition on your shelves when you are into medieval (embroidered) textiles. My main reason for visiting the St Annen Museum now, was that the cope hood with a stumpwork version of St Georg and his pet was on display. This stunning piece of stumpwork embroidery was made around AD 1500 in Northern Germany. Sorry for those of you who think that stumpwork is an English invention. It is not. It was invented on the continent a good 100 to 150 years before 17th-century English stumpwork was made. Due to language barriers and not much appreciation on the side of art historians, these pieces have not gotten the scholarly attention they deserve. St George and his pet are pretty high on my recreation wish list :). Unfortunately, the construction of his head needs the help of a specialist wood cutter and a lot of trial-and-error. But this is definitely something I want to tackle in the future!

Literature Borkopp-Restle, B., 2019. Der Schatz der Marienkirche zu Danzig: Liturgische Gewänder und textile Objekte aus dem späten Mittelalter. Berner Forschungen zur Geschichte der textilen Künste Band 1. Didymos, Affalterbach. Meller, H., Mundt, I., Schmuhl, B.E.H. (Eds.), 2008. Der heilige Schatz im Dom zu Halberstadt. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg.

11 Comments

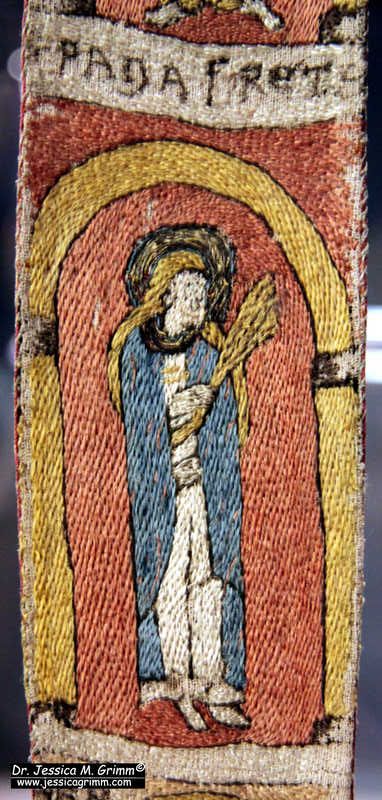

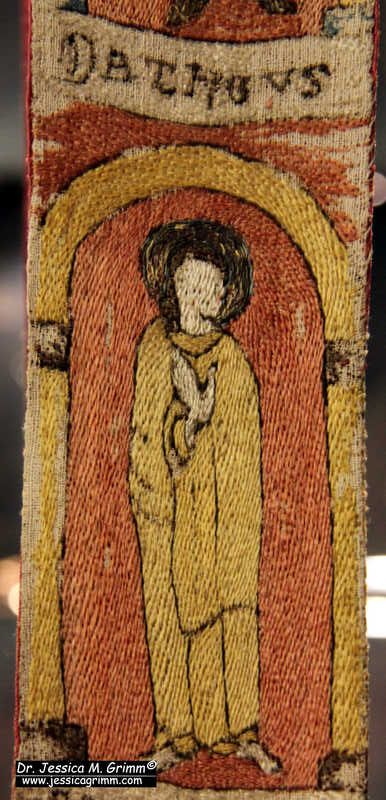

Today, we are going to revisit the Uta-chasuble in Marienberg Abbey in Southern Tyrol (Italy). I originally visited the small museum in 2017, but I was never able to lay my hands on a publication. Last week, however, I found the only publication on this extraordinary piece in my favourite second-hand bookstore on the internet. So here comes my updated blog post on the Uta-chasuble. During my second trip to Northern Italy, I visited the Benedictine Abbey of Marienberg in Mals. Their museum is also part of the exhibition 'Samt und Seide 1000-1914: Eine Reise durch das historische Tirol' curated by the European Textile Academy (you can read about my first trip here). This museum houses one of the crown jewels of medieval embroidery in Europe: the Uta chasuble stitched around 1160 AD. To give you an idea of its importance, the oldest pieces in the famous 'Opus Anglicanum' exhibition in the Victoria & Albert museum in 2016/2017 were a seal bag from 1100-40 AD and several embroidered fragments from 1150-1200 AD. The oldest embroidered complete chasuble in the exhibition was the Clare Chasuble from 1272-94 AD! Similarly, the oldest embroidered chasubles in the exhibition 'Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden' in the Catharijneconvent in Utrecht in the Netherlands in 2015 is dated to the late 15th century. High time I introduced you to the Uta-Chasuble! The above pictures show you the Uta-Chasuble from the front and the back. In the right picture, you also see the matching stole. The embroidery shows a tree of life spread all over the chasuble. Inside the top part of the forked cross, you see Jesus inside the mandorla flanked by two angels and several stars and crowns. Jesus is seated on a throne, holding a book in his left hand and raising his right hand in a blessing. This is the so-called Christ Pantocrator. On the back of the chasuble, we see the Agnus Dei flanked by the symbols of the evangelists. The evangelists are portrayed as winged figures on which only the heads differ (Matthew man, Mark lion, Luke ox and John eagle). Originally, the chasuble would have been a bell chasuble. At some point, probably in the 14th or 15th-century, the sides were cut for easier movement. Here you see a detail of the back of the chasuble, just inside the forked cross, showing two of the winged evangelists. You can see every silken stitch (they are between 2-7 mm long). In the literature, the stitch is described as alternating rows of stem stitch. However, I think the stitch is brick stitch. This was a stitch particularly popular in the German-speaking areas. You can also see the faint lines of the original drawing. It looks like the design drawing was done free-hand. There is also some couching with metal thread left on the winged evangelists (single metal thread couched with red silk). Two different types of gold thread were used in the embroidery: Membrane gold with a white linen core and gilt silver foil wrapped around a yellow silken core. These parts of the embroidery are so well preserved because a forked cross was appliqued onto the embroidery. This forked cross was made by cutting up a precious piece of lampas silk. This silk came from Persia and dates to the 10th or 11th-century and is thus much older than the chasuble. The pattern on the purple silk consists of pairs of parrots. These birds are framed with circles filled with Kufic script and small animals. Now, why would you cover parts of your embroidery with pieces of silk? Once the silk was taken off the chasuble it revealed that they covered the seams between the different parts of the chasuble. It turns out that the chasuble consists of seven separate pieces. And they were clearly embroidered by different people. When they stitched the embroidered pieces together to form the chasuble, the difference in stitch length and direction was far too noticeable. That's why the seams were covered with the strips of silk. Here you see one of the angels flanking Jesus inside the mandorla. Pattern couching is present on Jesus' clothing. Instead of the now common bricking pattern, the couching pattern forms a slanting line. This pattern can be seen more often in medieval goldwork embroidery. The colour palette for the silk embroidery on the fine linen background (43-58 ct) is quite restricted: red, yellow, blue and brown. Accompanying the chasuble is a matching stola showing saints. In the picture on the left, you see St. Panafreta, one of the 11.000 virgins following St. Ursula to her martyrdom in Cologne. On the right, you see St. Datheus. He was archbishop of Milan and opened the first home for abandoned children in 787 AD.

Oral history claims that the chasuble was stitched by Uta von Tarasp and her ladies. Uta and her husband Ulrich were the beneficiaries of Marienberg Abbey. But who drew the pattern? Was it the same person who painted the frescoes in the Abbey Crypt? And where were the precious embroidery threads coming from? A large quantity of consistently spun and dyed silk thread as well as metal threads. Apparently, the silk threads came from Sicily. Did Uta and her ladies work the chasuble on large embroidery frames in a room in Tarasp castle? How was the work divided amongst the women? How fine were their needles? Did they have artificial lighting or could they only work in daylight? Would there be music played or a book read aloud when they were working? Let me know what you think! Literature Hörmann-Weingartner, M., 2004. Die Uta-Kasel in Kloster Marienberg, in: Stampfer, H. (Ed.), Romanische Wandmalerei im Alpenraum. Veröffentlichungen des Südtiroler Kulturinstitutes 4. Südtiroler Kulturinstitut, Bozen, pp. 129–148. Over the past three weeks, I have compared two orphrey figures of St John (Another John and his identical twin, comparing face and hands & comparing the clothing). In this final blog post, I will compare the or nue and the additional goldwork embellishment. For me, "slow looking" at historical pieces of embroidery is a great form of CPD (Continuing Professional Development). It comes close to the old way of learning where an apprentice would copy the works of the master. Especially when it comes to or nue, copying a piece from the late 15th- or early 16th-century has proven to be essential in mastering this exquisite embroidery technique. In the process, I probably solved the mystery of the two St Johns. At first glance, the or nue of the red cloaks looks pretty similar. However, when you look at the red cloak in the above pictures: which one gives the better illusion of being three-dimensional? For me, it is ABM t2165 and this is not due to being in a better condition. The folds are more realistic. This is achieved by using one extra shade of red for the shading and the ever so slight curving in the lines of stitches that form the folds. Contrary, the folds of OKM t90a are very straight and the shading is crude. Just like with the silk shading of the green undergarment, the stitcher of ABM t2165 knew what he was trying to convey. The stitcher of OKM t90a just filled the different parts of the design and hoped for the best. The stitcher clearly did "not see" it. As the clothing as a whole (green undergarment and red cloak) was rendered in the same way within the same piece, it is clear that the same stitcher was responsible for the silk shading and the or nue. When we look at the cup St John is holding, we see marked differences. And this is interesting in itself! Where the way the clothing was embroidered was apparently very standard (green for undergarment and red for cloak), the stitcher could go wild with the little details. Note: you can clearly see that the cup is "part" of the or nue of the red cloak. The cup of ABM t2165 is expertly worked with a lovely rim worked of a curved pair of goldthreads (two rows on the front and only one row on the inside of the cup) and topped by a single row of twist. The cup has a clear outline achieved with shading on the right and couched red silk on the left to hide the turns of the goldthreads. The "seam" between the stem and the cup is decorated with foliage formed by a pair of couched goldthreads and couched brown silk. The foot of the cup is ornately faceted with couched pairs of goldthread and a rim of twist. The whole cup is clearly recognisable as a Gothic cup of the time. Contrary, the cup of OKM t90a is crude with poor shading and fewer details. The twist is either made with an extra strand of yellow silk or these are the very visible couching stitches. The clothing of St John is further embellished with goldthreads stitched over the silk shading and the or nue. In both cases, normal goldthread and twist were used. But, as seen with everything else (bar the face!) the stitching on ABM t2165 is more refined. Looking at all the evidence, I don't think the two versions of St John were stitched by the same embroiderer. Not even several years apart. The stitcher of ABM t2165, although not an expert with faces, is clearly the better artist with an expert understanding of how to suggest the third dimension. I get the feeling that ABM t2165 is the work of a single artist, whereas OKM t90a is the work of two stitchers. One mediocre stitcher for the figure and an absolute ace for the face. Could they be produced in the same workshop? Yes. After all, in a large workshop such as that of Jacob van Malborch in Utrecht (AD 1500-1525), many different stitchers were working on the commissions. But something isn't quite right ... OKM t90a was certainly stitched by or in the workshop of Jacob van Malborch as we have the work contract from AD 1504. The reason why ABM t2165 is ascribed to Jacob van Malborch is due to the ink inscription on the orphrey beneath the loose figure: I.F.I.S. According to Saskia de Bodt, these letters stand for: I(acobus) F(ecit) I(pse) S(anctam) or Jacob made this saint. Now, ABM t2165 contains four saints in total. Two still attached to the orphreys and two loose ones of which one is our St John. The two attached figures are quite different in style from the two loose figures ... St Peter and Mary Magdalene have very pretty faces, but crude silk shading for the undergarments. And simple reduced shading of the or nue with very straight lines for the folds. Sounds familiar! These figures are comparable with OKM t90a. Those that were definitely made by or in the workshop of Jacob van Malborch. The two loose figures of ABM t2165 are not. And a tiny remark in the online catalogue entry proves my point: "Het borduurfragment is groter dan de uitsparingen in de linnen ondergrond. Mogelijk was er eerder een andere Petrus op aangebracht." (The embroidery fragment is larger than the voided areas on the linen background. Maybe originally a different St Peter was once attached.). If St Peter is not original, why should St John be? When vestments wore down, repairing them by patching them with parts of other worn down vestments and/or by adding new parts was common practice (even in rather recent times to make them saleable on the antiquities market). It is very well possible that ABM t2165 is the result of such recycling!

Literature Leeflang, M. & K. van Schooten (eds), 2015. Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden. Utrecht: Museum Catharijneconvent. Let's explore last week's rationale a bit more. This rare medieval vestment is modelled on the ephod of the Jewish high-priest. Chapter 28 of the bible book Exodus described the garments that need to be made by skilled craftsmen for Aaron and his sons in great detail. Verses 6-14 tell us about the design of the ephod: "And they shall make the ephod of gold, and violet, and purple, and scarlet twice dyed, and fine twisted linen, embroidered with divers colours. It shall have the two edges joined in the top on both sides, that they may be closed together. The very workmanship also and all the variety of the work shall be of gold, and violet, and purple, and scarlet twice dyed, and fine twisted linen. And thou shalt take two onyx stones, and shalt grave on them the names of the children of Israel: Six names on one stone, and the other six on the other, according to the order of their birth. With the work of an engraver and the graving of a jeweller, thou shalt engrave them with the names of the children of Israel, set in gold and compassed about: And thou shalt put them in both sides of the ephod, a memorial for the children of Israel. And Aaron shall bear their names before the Lord upon both shoulders, for a remembrance. Thou shalt make also hooks of gold. And two little chains of the purest gold linked one to another, which thou shalt put into the hooks." (Douay-Rheims Bible which is closest to the Vulgate Latin version widely used in medieval Europe). The text makes clear that the ephod was a very precious garment with gold, gemstones and costly dye-stuffs. And it also explains the shape of the medieval rationale with the two patches on the shoulders. The name "rationale" is derived from the translation of the priest's ephod (Hebrew), to logion (Greek) into rationale (vulgate Latin) (Miller 2014, 64). Who was allowed to wear a rationale? Bishops were allowed to wear the rationale over the chasuble. Although it seems that this special vestment was sometimes granted by the pope to a particular bishop (Pope Agapetus II apparently granted one to the see of Halberstadt, Germany, before AD 984) other bishops simply copied its use. It became fashionable in the 11th- and 12th- century in Germany and then spread to France and England in the 13th-century. Curiously, Italian bishops, with the exception of the sees of Aquileia and Monreale, do not seem to have been keen on wearing it (Miller 2014, 65-66). Presently, only the bishops of Eichstätt and Paderborn (Germany), Toul-Nancy (France) and Krakow (Poland) wear this medieval vestment on special occasions. The rationale from Bamberg belongs to the so-called Kaisergewänder (held at the Diözesanmuseum Bamberg) and was made between AD 1007 and 1024 in the realm of Holy Roman Emperor Henry II. The embroidery is made with very fine, near-pure goldthreads in normal couching on dark-blue silk samite imported from the Byzantine Empire. Although presently the embroidery is applied to a bell-chasuble made of blue Italian silk damask from AD 1450, the original embroidery was also part of a bell-chasuble rather than a separate vestment such as the Regensburger rationale. The embroidery depicts scenes from the Apocalypse, an allegory of the church and busts of the apostles (Kohwagner-Nikolai 2020, 190-196). The rationale from Regensburg (part of the Regensburger Domschatz) was made in AD 1314/1325, possibly in Regensburg (Germany). It was made at the behest of king, and later Holy Roman Emperor, Louis IV, called the Bavarian (AD 1282-1347). He gifted it to bishop Nikolaus von Ybbs (AD 1270/1280-1340), bishop of Regensburg. It is made of linen embroidered with very fine gold- and silver threads as well as silks. On the front, we see an allegorical depiction of the church. On the back, we see Christ in the mandorla surrounded by angels, symbols of the evangelists and the agnus dei. The elongated slips on the front and the back contain the busts of the apostles. The two shields on the shoulders contain female allegories of Psalm 85:10. Each depiction can be identified by stitched texts in either Latin or German (Kohwagner-Nikolai 2020, 237-240).

For a detailed description of the embroidery techniques and materials used for both rationale, we will have to wait for the publication of the research project results of the "Kaisergewänder", later this year. Literature Kohwagner-Nikolai, T., 2020. Kaisergewänder im Wandel - Goldgestickte Vergangenheitsinszenierung. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner. Miller, M.C., 2014. Clothing the clergy. Cornell University Press. We have no contemporary eye-witness accounts of the first Christmas. Still, quite a few of the nativity scenes in the Western world look very much the same. How did that happen? And how does this relate to a group of almost identical embroidered vestments made in Germany in the second half of the 15th-century? What technological innovation was made to ensure near-identical serial production? A perfect story to explore in the last days running up to Christmas 2020! As said, conventional knowledge has it that none of the witnesses of the first Christmas left a written and signed account of the events. But through the ages, some people have claimed that they were transported back in time and witnessed the scene. They had a revelation. For Western Art, the revelations of Saint Bridget of Sweden (AD c. 1303-1373) are very important. Saint Bridget describes the scene as follows: Mary is a bare-headed blond-haired woman who together with Joseph kneels in prayer over the infant Jesus who radiates divine light. Saint Bridget became a bit of a celebrity during her life and her revelations were turned into images that went viral in most of Europe. It successfully replaced earlier conventional pictures of the nativity where Mary is reclining on a bed (still popular in Orthodox Christianity). You can see an example on the chasuble from St. Paul im Lavanttal (at the top on the back; the scene with the red background). The images of the revelation of Saint Bridget were so popular, that they were also reproduced in embroidery for the orphreys found on chasubles. These orphreys are so similar that their designs must have a common source. Printing on paper with the help of woodcuts and metal engraving was invented in the first decades of the 15th-century and quickly became popular to cheaply spread imagery. Research into the composition of the design lines on some of these orphreys has shown that these designs were likely printed onto the embroidery fabric too. If you click on the pictures of the pieces from the MET and the Wartburg, you can explore further pictures on the institution's websites. And here is a fragment kept at the Bayrische National Museum (Inv. Nr. T297) with the singing angels. Although these embroideries were made in serial production, slight variations do exist. Not only in the colours used, but also in the number or arrangement of the figures. In this case, a more pleasing composition was achieved by adding a third angel. There are quite a few other examples out there, but I don't have pictures of them that I am allowed to publish. If you would like to dive into the topic a little further, please explore the literature.

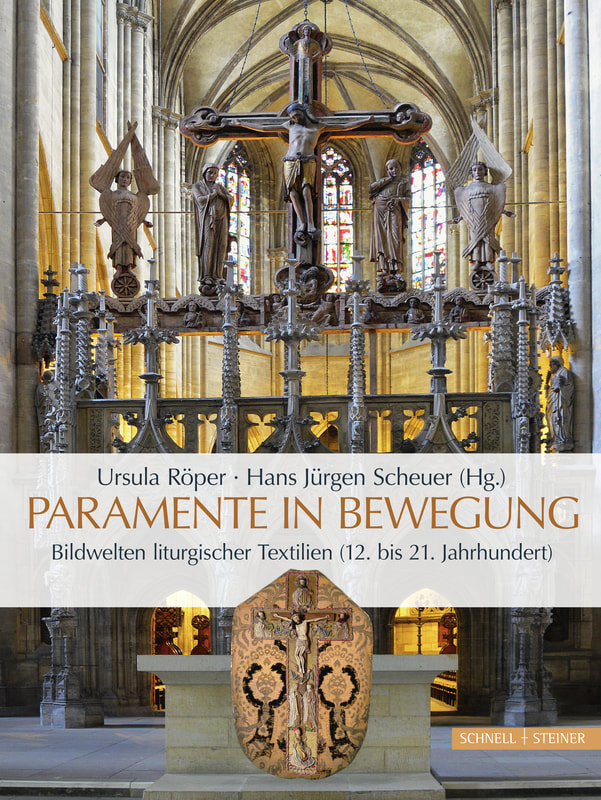

Literature Fricks, J. von, 2010. Serienproduktion im Medium mittelalterlicher Stickerei - Holzschnitte als Vorlagematerial für eine Gruppe mittelrheinischer Kaselkreuze des 15. Jahrhunderts. In: U.-Ch. Bergemann & A. Stauffer, Reiche Bilder. Aspekte zur Produktion und Funktion von Stickereien im Spätmittelalter, Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner. Wetter, E., 2012. Mittelalterliche Textilien III. Stickerei bis um 1500 und figürlich gewebte Borten, Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung. The German publishing house Schnell & Steiner has a number of interesting books on medieval vestments in their programme. Discounts are applying until the 23rd of December. So if you are thinking of adding books to your library, this is a good time! However, it is a German publishing house and the books are in German. And one, in particular, might look like a good idea, but maybe isn't. That's the one I am going to review here. Don't get me wrong, it is a great book! But as it is the result of a multi-disciplinary conference with theologians, philosophers, art-historians, Germanists, archaeologists, anthropologists and philologists, it isn't for everyone. Paramente in Bewegung (paraments in movement) is an edited volume of 17 papers published in 2019. These papers have one thing in common: they are all theoretical. Only one author started out with a practical apprenticeship in tailoring. All others are academics through and through and they write for an academic audience with German as their native language. Although I am fluent in German, I had to look up many words in the theological and philosophical papers. And even then I was often left wondering what the author was saying ... However, a couple of papers helped me to better understand the context the embroidery I admire so much functioned in. So, from the point of view of an academic researcher into medieval embroidery, this book is a must-have on your shelves.

Jürgen Bärsch writes about the liturgy and the church building in the late medieval period. Even those who have attended a modern Catholic mass will soon realise that late medieval mass was quite different. Taking communion was rare and instead the elevation of the host was the pinnacle of each mass. Believers would hasten through the church building to attend multiple elevations as masses were not only held at the main altar but also at the many altars belonging to wealthy families, brotherhoods or guilds in the aisles. And as Stefanie Seeberg explains in her paper, the paraments used during these sacred performances all stood in relation to each other and to the building they were functioning in. Similar scenes were repeated on the vestments as seen in the architectural decoration of the church building (wall paintings, leaded windows, sculpture). Most people couldn't read nor understand the Latin the priest was using. But by constantly seeing the same images, the Christian message was understood by all. Additionally, an interesting observation was made. As the priest becomes part of the whole scene, he as a person is no longer important. However, as we nowadays see these splendid vestments in isolation, we often draw the opposite conclusion: the wearer must have stood out. For the two papers on the theological and historical explanation of vestments (Rudolf Suntrup and Dina Bijelic), there is a better alternative available in English: Clothing the Clergy by Maureen Miller. I've reviewed this book a while ago. The papers by Britta-Juliane Kruse and Tanja Kohwagner-Nikolai explore paraments in the reformed convents of Lower Saxony. They are commonly called Heideklöster as they are located on the Lüneburg Heath. They escaped the dissolution but changed from Catholicism to Lutheranism. They are famous for the large medieval embroidered tapestries stitched entirely in Klosterstich (Bayeux stitch). The papers attest to the high level of education in these convents. The daughters of the nobility were able to decode the complex stories on the paraments. They had read the classical literature and knew how these motives related to the Christian faith. Studying the actual embroideries also reveals that the ladies themselves stitched and designed these tapestries. And they were proud of their excellent work: later pieces are signed. Stefan Michel and Evelin Wetter write interesting papers on the perception and use of vestments after the Reformation. Whilst the more radical Calvinists objected to the continued use of the Catholic vestments, Luther actually saw nothing amiss with the practice. As long as people did not worship the depictions. The special clothing was only there to support the sacredness of the mass. We now often think that all depictions were radically removed from every church that became reformed. This is true for most churches in the Netherlands, Scotland and Switzerland as they followed the teachings of Calvin. However, large tracts of the Germanic lands followed the teachings of Luther. And they often continued using, repairing and replacing their splendid medieval vestments. Imke Lüders' paper on the use of images of skulls and bones on burial vestments makes for an interesting read too. And Klaus Raschzok's paper on the re-discovery of paraments in the Lutheran churches shows that this movement was particularly influenced by the 19th-century Gothic revival in the Catholic church. This movement had started in England with the influential publication by August Welby Northmore Pugin: "Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume". You can download this publication for free and marvel at the beautifully hand-coloured designs in the second half. En passant, the paper goes into the question of who should make fitting paraments for the reformed church. One movement wanted to go the professional route by educating deaconesses both in theological design and in the needle arts. The other movement emphasised that each godly woman should help make paraments for the church instead of using her needlework skills to frivolously decorate her own home ... Don't you love it when men discuss how we should use our skills? I hope the above book review helps you to decide if this book is for you or not. Very soon, three volumes will be published on the medieval gold-embroidered vestments from Bamberg by the same publishing house. As soon as they arrive, I will review these too. They look very promising! Literature Röper, U. & H. J. Scheuer (eds), 2019. Paramente in Bewegung. Bildwelten liturgischer Textilien (12. bis 21. Jahrhundert), Schnell & Steiner: Regensburg. ISBN: 978-3-7954-3338-3. P.S. In an attempt to do my bit to break the data monopoly of Google and Facebook, I have transferred all my videos to the video platform Vimeo. Please give me a follow! And in order to have more time for embroidery and researching embroidery, I have decided to close my Instagram and Pinterest accounts. No wonder I have suddenly time to read whole books and a newspaper :). During my break from blog writing and after the success of the first online goldwork course, I have come up with a new online course: Medieval goldwork techniques - a journey through 500-years of embroidered history. In this new ten-week online course we will explore different forms of couching: underside couching, pattern couching, couching over padding and the queen of couching techniques: or nue. We will explore each technique in its (art) historical setting. In each sample worked we will use as authentic materials as feasible. The beautiful goldwork techniques of the Middle Ages deserve precious gilt threads and real silk! Over the past five years, I have travelled extensively to visit museum exhibitions, research facilities and libraries in Germany, the Netherlands, France, Austria, England, Italy and Lithuania. Many of these trips were covered on this blog. The resulting research now forms the basis of the course. By attending the course you will gain in-depth knowledge of how medieval goldwork embroideries were made. What technical inventions revolutionised the process and the workshop setup. What inspired the stylistic language? You will learn about the close relationships between embroiderers, goldsmiths, painters and sculptors. Who were these embroiderers? Did they see themselves as artists? How were they organised? Who did they work for? The core of the course form the embroidery samples you will work. They are all inspired by actual medieval embroideries. You will handle luxury fabrics like samite and silk twill, as well as high-quality gilt threads and different kinds of beautiful silk yarn. After taking this course, you will know the benefits of using madder, sienna and iron gall ink. This course is directed at embroiderers of all levels. With the possible exception of or nue, none of the techniques are (technically) difficult. The techniques covered will form the basis for future (online) historical goldwork embroidery course I am developing. The medieval goldwork course will start February 2021 (registration will start 1st November). This enables me to assemble a full kit and get it shipped in time to all participants. Class size will be limited to 15 to enable me to give proper attention to each of the students. Each lesson will comprise of a PDF-download with all the historical and technical information on the particular technique explored, a video abstract of that information, a video of me working the sample and giving tips, a zoom-meeting where you can meet fellow students and discuss the lesson and a classroom on NING where you can find all the course material and keep in touch with your fellow students. And as always, I am only an email away!

Updates on the course and registration will be disseminated through this blog and my newsletter. Looking forward to sharing my enthusiasm for medieval goldwork embroidery with you in this new course! If you are after a book with lots of pretty pictures of medieval embroidery on vestments, this is not it. Yes, there are some pretty pictures in there, but it is not what the book is all about. Why do I still think it is worth your time? It has a very interesting chapter on the role of women in making vestments and donating them. As the author places their making into the wider context of church reform during the Middle Ages, it explains a lot about the position of women today in the Western world. From the late 12th-century onwards, increased urbanisation leads to a dominance of the textile trades by men. Especially the 'higher end' of the market is dominated by them. That's why I have written in several blog posts that certain vestments I saw in museums were most likely made by men. The written data for the Late medieval period and beyond from the Netherlands does, for instance, not mention one female embroiderer. But this had not always been the case. The author, Maureen Miller, writes that when we know the name of the maker of earlier vestments, it is always a woman. And here the labour is divided up too: slaves for the 'hard labour' of growing, spinning, weaving, dying etc. and elite women for the fashioning of the vestment. For the more elaborate vestments, male religious would assist with the designing. Why would women spend time and money on creating (and maintaining) these elaborate vestments? Maureen Miller comes up with several explanations. Firstly, from the ninth century, ecclesiastical legislation prohibited women from entering the church sanctuary or come near the altar. By providing vestments, these women were present at the altar. Secondly, by cultivating such a relationship with clergy, these women could exercise some influence for themselves, but most likely for their families. Maureen Miller thus rightly asks how freely were these gifts really given? In addition, these relationships between elite women and clergy were always viewed with suspicion. On the one side, elaborate stories about the piety of the women who worked these vestments were drawn up (reciting scripture or singing psalms whilst working). On the other hand, there were plenty of stories in which the 'lewdness of the female maker' transferred through the vestments onto the wearer. These poor clergy felt mightily uneasy when it came to women making and maintaining their intimate clothing.

At the same time, there is a wider reform going on in the church. In order to claim status and visualise hierarchy, an ornate style of vestments started to emerge in the 9th century in Anglo-Saxon England and Francia (modern-day Normandy and parts of Belgium). By the 11th-century it had spread throughout Europe. The makers of this new ornate style were women. They (unwittingly?) provided part of the means with which the Gregorian reforms could be implemented (most notably clerical celibacy). These were particularly bad for the position of European women as they emphasised extreme notions of purity. These ideas live on in particular in the Catholic church till today. And those poor holy men? They were relieved when they could order their splendid vestments from men in urban centres. They no longer needed to foster close relationships with women to obtain and maintain their vestments. For the visualisation of their status, they no longer depended on women. Women lost a way to exercise their influence. But they lost so much more. Till today, in many Christian traditions, women are not seen as pure enough to serve at the altar. Argue in the other direction and time might have come to strip these holy men of their fancy clothes in order to restore some much-needed balance between the sexes! Literature Miller, M.C. (2014): Clothing the clercy. Virtue and power in Medieval Europe, c. 800-1200. Cornell University Press. Today I am going to share some more medieval eye-candy with you. This time we are going to explore some of the goldwork embroideries made in France during the 13th-15th centuries. Particularly Paris enjoyed a boom in embroidery during the 13th-14th centuries as the royal court resided there. Written guild regulations from 1292-1295 and 1316 suggest that female embroiderers were the norm and that the apprenticeship lasted eight years. However, the embroiderers attached to the King and the princes have names such as Robert de Varennes or Sandre Lappert. So was the situation in medieval Paris really so different from that in the Low Countries? I doubt it. Prestigious commissions from the French King and his princes were likely given to male embroiderers. The first piece I would like to draw your attention to is a mitre worn by the abbot of the ancient abbey of Sixt, Upper-Savoy. The very fine silk- and gold embroidery is executed on white silk (either samite or serge) backed by linen. The silk embroidery is executed in split stitch and stem stitch. The goldwork embroidery is all done in couching. Although the embroidery was executed by embroiderers from Paris, the drawings were likely made by Jean le Noir, a famous illuminator who had a daughter, called Bourgot, who assisted him. I particularly like how the wings of the angel are placed so that they fit the sloping side of the mitre just perfectly. Another piece that blew my mind was the mitre created for Sainte-Chapelle around 1375-1390. There's so much going on on this relatively small object. And the scenes are adorable. Look at the ox and the ass. They make me smile :). The amount of padding on this piece is rather incredible too. And I just love the tiny seed pearls. It makes it all looks so over the top, yet so coordinated. The treatment of the garments is quite different from the usual or nue or pattern couching seen on so many of these pieces. Instead, the different parts (folds) of the garments are created by laying separate pairs of passing thread in different directions. The folds are accented with couched dark brown silk. Very clever indeed. The last pieces of embroidery I would like to draw your attention to are known as the embroidered cycle of the legend of Saint Martin. This impressive, but incomplete, collection of embroidered orphreys was made for a single altar in a church or chapel. They thus show the medieval opulence when it comes to liturgical vestments. Due to the fact that these pieces were created at the court of Rene of Anjou (1409-1480) we know the painter of some of the designs: Barthelemy d'Eyck and the embroiderer who executed them: Pierre du Billant. It probably helped that both men were related.

The embroidered orphreys are now dispersed over four museums in Paris, Lyon, Baltimore and New York. Their original layout has been lost due to more modern up-cycling. Have a look at the very fine silk shading on the drapery of the clothing on some of the figures (there's definitely more than one embroiderer at work as there are marked differences in quality between the orphreys). The brightness of the colours after nearly 600 years is simply incredible! Literature Descatoire, C., 2019. L'art en broderie au moyen age. Musee de Cluny. ISBN: 978-2-7118-7428-6 . P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! At the beginning of January, I and my husband were lucky enough to be able to visit the embroidery exhibition in Paris. Today I'll show you some stunning pieces from the Opus Anglicanum section. The term for this type of embroidery from the 12th-14th centuries translates as 'work from England' and usually consists of very fine silken split stitches and underside couching. It was greatly valued throughout Europe especially, but not solely, for religious purposes. Therefore, you will find these stunning pieces of embroidery in museums all over Europe. But beware: not all Opus Anglicanum embroidery was actually made in England or by English hands. Medieval Europe was already so well connected that both ideas and people travelled a lot. The graves of bishops are a great place to search for medieval embroidery. Bishops were usually laid to rest in their finery in a grave with better preservational conditions than Joe Average. Antiquarians from the 19th century knew that too and when these graves were opened for whatever reason, they brought their scissors along. This is illustrated for instance on a pair of liturgical sandals from a grave from the Cathedral of Saint-Front in Perigueux: three different museums own pieces of the same pair of sandals. Today, many museum visitors turn their noses up when they see these brownish fragments of textile. They are mostly not 'pretty' in the usual sense. But I was very pleased to see that Musee de Cluny devoted a whole display case to these extraordinary finds. For obvious reasons, the levels of lighting were lower than in the rest of the exhibition so my pictures are sometimes a little dark. Nevertheless, look at these stunning patterns of birds and scrolling in very fine underside couching! Another stunning piece of embroidery on display was the above panel with the martyrdoms of the saints. There is a second panel too with female saints. Both are kept in different museums in Belgium but originate from the same church in Namur, Belgium. It was in use as an altar frontal but might have originally been a vestment. The embroidery on this piece is absolutely immaculate and very fine. I particularly love the different goldwork couching patterns in the background and the immense detail on the horse. Although only the above panel was on display in Paris, both panels were displayed at the Opus Anglicanum exhibition in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London a few years ago. One of the biggest pieces of embroidery on display were the fragments of a horse trapper (a protective garment for a horse in battle or tournament). It was unfortunately impossible to capture all (over 20, many quite small) fragments in one picture. The detail of the goldwork embroidery is amazing. The lion's mane and hairy claws are so full of movement through laying the goldthreads in different directions. In amongst the bodies of the lions are many small human figures in courtly dress. They clearly show how to embroider on such a difficult fabric as velvet: cover it with a thin piece of silk. When the embroidery is finished, cut the excess silk away. Although this piece of embroidery comes under Opus Anglicanum it does not show any underside couching and only small areas of split stitch (the silken parts of the claws). Instead, the goldwork is all 'normal' couching and the small figures and the foliage are stitched in running stitch (hence you can see the silk that was used to keep the hairs of the velvet at bay when stitching). It is said that in using these two embroidery methods the actual embroidery would take much less time then when split stitch and underside couching were used. I agree when it comes to the split stitch versus the running stitch. The latter is much quicker as it covers more ground with fewer stitches. However, I am not so sure that normal couching is that much quicker than underside couching. I now practice both and the only marked difference for me is that underside couching is harder on your body due to the slight extra force you need to apply with every stitch. By the way, these fragments have an interesting 'upcycling' story to them. The horse trapper was probably originally made for King Edward III. He was a guest at the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) at Koblenz, Germany, in AD 1338. The horse trapper probably remained in Germany as a royal gift. It was turned into a set of vestments for the Altenberg Abbey. These were dismantled in 1939 to once more show the original horse trapper. There were many more beautiful pieces on display in this part of the exhibition. For those of you who were not able to visit in person, I can highly recommend the exhibition catalogue. It is packed full with good quality pictures and many close-ups. More on my textile adventures in Paris in further blog posts!

Literature Browne, C., G. Davies & M.A. Michael (eds.), 2016. English medieval embroidery Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press. ISBN: 978-0-300-22200-5. Descatoire, C., 2019. L'art en broderie au moyen age. Musee de Cluny. ISBN: 978-2-7118-7428-6 . Michael, M. (ed.), 2016. The age of Opus Anglicanum (= Studies in English medieval embroidery 1), Harvey Miller Publishers. ISBN: 978-1-909400-41-2. P.S. Did you like this blog article? Did you learn something new? When yes, then please consider making a small donation. Visiting museums and doing research inevitably costs money. Supporting me and my research is much appreciated ❤! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed