|

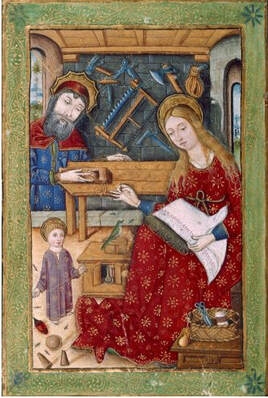

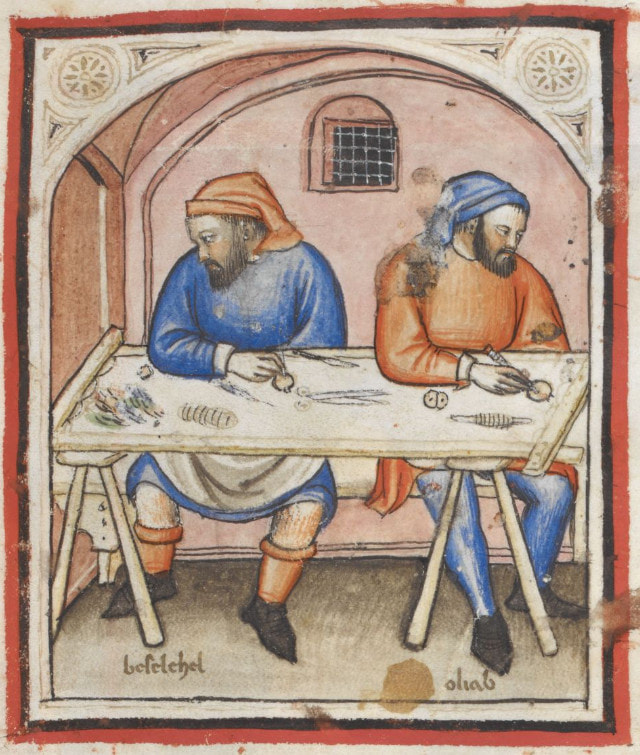

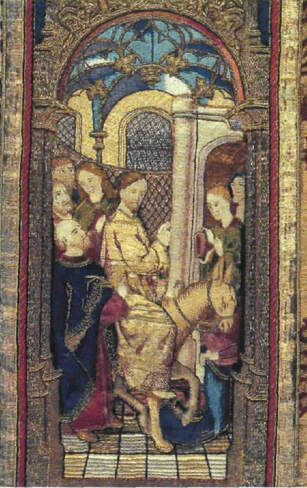

As I was studying a Portuguese book on medieval embroidery, I came across an article by José Alberto Seabra Carvalho on the craft of embroidery in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period. Although he acknowledged that some embroidery was undertaken by the women in noble households and by nuns in convents, he also came to the conclusion, by studying the surviving pieces and combining them with the historical records, that those were made by men in commercially run workshops. Their quality is simply too high. It requires many years of training before one is able to make a living from making orphreys. At the same time, he briefly investigates this ideal of the 'pious woman'. As long as her hands were busy doing needlework, she could not daydream and get into trouble. In addition, her handy work could contribute a bit to the household. These opinions are not his but come from contemporary sources. And here we have precisely this duality: needlework itself is not much valued as it is done by women to keep them from having a wandering mind. While at the same time, commercially produced goldwork embroidery requires many years of training and is thus the domain of men. The duality and stigma embroidery 'enjoys' today is thus an old one. Art versus craft. And only for women. Let's explore what that looks like in medieval and early modern images! Female embroiderers are depicted in two different ways: stitching in hand or sitting behind a slate frame resting on trestles. Usually, it is not ordinary women that are depicted embroidering. Especially not in the earlier periods. It is either Mary employing a needle or a queen/noblewoman stitching. Stitching in hand requires very little in terms of professional tools. Mary on the left has a simple basket filled with scissors and a bobbin with thread. This is in strong contrast to Joseph's array of professional carpenter tools hanging on the wall. By the way: I don't think St Francis would approve of Jesus tying a rope to a bird :). Contrary, Mary on the right, is shown in a much more professional setting. She uses a large slate frame and a pair of trestles. The spool she is holding might be wound with gold thread. It looks like she is using her slate frame and trestles set-up as a kind of working table with balls of yarn laying on top. Some people argue that this shows Mary making a tapestry instead of an embroidery. However, I think she is in the process of couching down a gold thread on top of red and green silk embroidery. In both images, combining embroidery with childcare seems not to be a problem. Maybe that's why the child is harassing the bird? Male embroiderers, on the other hand, are depicted in one way only. As professionals. No cosy stitching whilst watching a child. Maybe medieval and early modern men were just not prone to 'daydreaming and getting into trouble'?

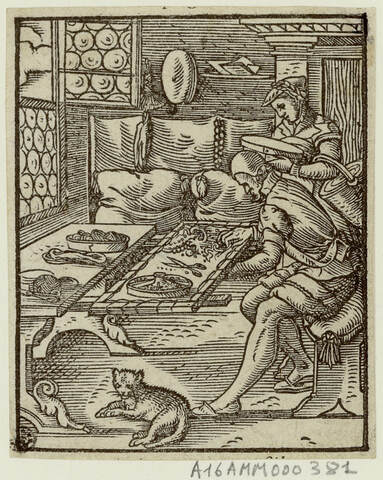

The above illustrations show men sitting behind slate frames in the typical posture of an embroiderer. One hand above the frame and one hand below to speed up the process. And I love the non-ergonomic posture of the man on the right. At least none of the above men can be told off for crossing their legs :). By the way, I think we also see very realistic depictions of how these professional workshops were set up back in the day. The men on the left are probably working outside under a portico. Maximal use of daylight, but a bit sheltered from the weather conditions. The man on the right has the luxury of window glass. But he still needs to sit right in front of them and even needs to open the top window for clear, unfiltered daylight. The stereotypes depicted in the above images, some over 600 years old, seem to persist today. When I am demonstrating professional goldwork embroidery at my local open-air museum I get many stereotypical reactions. Many women equate what I am doing with cross-stitch embroidery. And when they hear that this is not my hobby, but my profession, I get 'the look'. It is not a kind look :). Some even react very irritated. How can a woman, who has gone successfully through university, want to stitch for a living?! How on earth did I sink so low? Very few women admit that they themselves stitch. And the ones that do, get younger from year to year. So, there is hope! Many men, on the other hand, have a very different reaction. They univocally acknowledge that what I am doing is very different from the needlework their mums and wives did or do. They are interested in my tools and the mechanics of it all. Some remark that this is 'typical' women's work. When I then explain that this was a male profession for hundreds of years, I have their full attention. Some even ask if I personally know male embroiderers (Gary Parr, you are getting famous here in Bavaria!). A few are so intrigued, they revisit the museum and seek me out to see how the work has progressed. And as they can precisely point out what I had accomplished last time, it is clearly about the embroidery and not about me :). I really hope that some people who see me stitch in the museum pick up a needle. Regardless of their reaction. Embroidery is fun! The ancient forms should be studied and revived. The professionalism of the makers should be acknowledged and valued. I hope you liked this blog post. Maybe it can contribute a bit of 'fact' to the craft versus art debate. Knowing that we are repeating the medieval and early modern idea of the 'ideal woman' when we see embroidery solely as a craft (in the modern sense), might make people think twice before they argue their case. The above images are not the only ones I have collected over the years. My valued Journeyman and Master Patrons will have access to a Padlet with 10 additional images. Literature Seabra Carvalho, J.A., 1993. O Ofício. In: T. Alarcão & J. A. Seabra Carvalho (eds), Imagens em paramentos bordados seculos XIV a XVI, Instituto Portugues Museus, p. 16-21.

14 Comments

In the last few years, there's been an increased focus on the benefit of needlework on your mental health. However, 'modern' principles of good mental health are sometimes also depicted in medieval embroidery itself. One such famous depiction is the scene of 'Noli me tangere' (cease holding on to me). It is based on a biblical story in the gospel of St John. Mary Magdalene returns to the grave site. She talks to a man whom she thinks is the gardener. He tells her not to hold onto him when she finally recognises him to be Jesus. Their former relationship has to change. Depending on what you believe, this is either because Jesus has died or because he just became responsible for the salvation of mankind and is now kinda busy. Either way, they need to let go of what has been. Being able to properly let go is a sign of good mental health. Let's have a look at the different depictions of this intimate encounter. Among the 1650 pieces of medieval goldwork embroidery, only 21 depict this particular scene. It is clearly not overly popular, but also not completely rare. The oldest pieces date to the 13th century and the youngest to the 16th century. By pulling them together, you start to observe some interesting things. Firstly, most of the embroideries depict Jesus as the risen Christ and not as a gardener. The first 'gardener-Jesus' is depicted on a cope from the St Marienkirche in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) (kept at St Annenmuseum Lübeck). It dates from after AD 1460 (but probably not long after). Between AD 1520 and 1530, the 'gardener-Jesus' becomes the norm. And you can clearly tell that the embroiderer knew what a gardener looked like and what equipment they used. In fact, the depiction of Jesus' shovel is so accurate, that medieval archaeologists have no trouble matching them to excavated originals. In the above picture, the brown silk embroidery represents the wooden part of the shovel and the silver threads depict the iron 'shoe' which protects the wooden edge and hardens it for digging. Neat, don't you think? Putting the 21 embroideries in chronological order also shows developments in embroidery techniques and materials. The two oldest pieces from the 13th century are very different. One is a case of Opus florentinum from Italy (kept in the Aachener Domschatz, inv. nr. T 01001). It shows this characteristic treatment of the golden background: string padding in the form of foliage. The gold threads have been couched over it to create an embossed look (as I don't own a picture of this piece, please compare it with this piece from the MET 60.148.1). The other piece, the so-called Hedwigkasel (now kept in the Muzeum Archidiecezjalne we Wroclawiu, nr inw. 23/29a), is very different indeed. It is worked on red silk and reminds a bit of the earlier Opus anglicanum pieces. The figures are completely worked in metal thread embroidery. Many different, often very intricate, diaper patterns have been used to fill in the different parts of the figures. It even looks like the embroidery is done in underside couching. In the later pieces, we see an increased use of the or nue technique. In the beginning (late 15th century), it is only used on parts of the clothing of the most important figure in the scene. Pieces from the 16th century, often show the use of or nue for the full width of the orphrey. Only bare skin is voided. Figures and background are worked in one go. And whilst the youngest piece is also one of the finest when it comes to the execution of the embroidery, two slightly younger pieces show the decline likely caused by the Reformation. And then there was this absolutely thrilling discovery of another 'twin image'. A chasuble (inv. nr. 138) held in the Frankfurter Domschatz shares an identical depiction of Noli me tangere with a chasuble (inv. nr. BMH t2912a) from the Museum Catherijneconvent. The embroidery techniques used differ a bit, but the design drawing is identical. I have alerted both museums to the discovery just in case they are unaware. As there seems to be little known about the piece in the Netherlands, finding a twin on a piece with known provenance is always very nice!

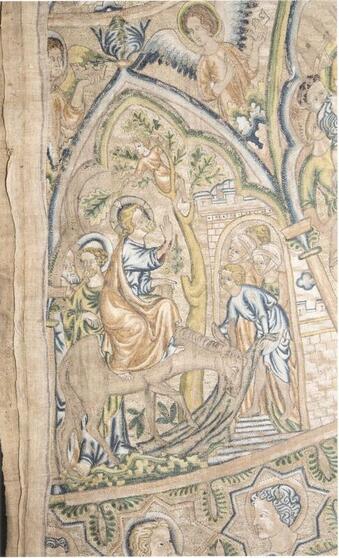

My Journeyman and Master Patrons have access to a Padlet on which all 21 pieces are introduced. Sometimes a question pops up in my mind in the middle of the night. These questions usually develop into delightful rabbit holes the next day. My latest 'in the middle of the night question' concerned the embroidered depiction of Palm Sunday. You see, some scenes were hugely popular in the medieval period, and we have many embroidered depictions of them. And then you have scenes that are very rare. Palm Sunday turns out to be one of these rare scenes. By now, I have looked at over 1650 pieces of medieval goldwork embroidery. That's about 4480 orphreys. Only three (!) of those depict the Triumphal entry into Jerusalem. But those three have a rather interesting story to tell. Let's hop down the rabbit hole! Two of the three orphreys depicting the Triumphal entry into Jerusalem look very, very similar. Above on the left is the scene as depicted on the Bologna cope. This is a famous cope made in the style of Opus anglicanum and it dates to the early 14th century. On the right, you see an orphrey on the chasuble of a Belgian bishop who reigned around the middle of the 15th century. That one was made between about 133 and 157 years later. Yet, the compositions of both scenes are eerily similar. Only the clothing of the Jerusalem citizen spreading a garment onto the street has adapted to the correct fashion of the time. Fascinating, isn't it? I think that both embroideries are based on the same image. Maybe from a famous illuminated manuscript or from a painting in a church. An image that was clearly widely known in Western Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries. Both embroideries are also testimony that the embroidery techniques can be very different and still produce two very similar pictures. Do click on the image on the right as it will take you to the KIK-IRPA database with many more pictures of the chasuble of bishop Chevot. The third image is clearly different. It comes from a chasuble belonging to an ornate associated with bishop David of Burgundy of Utrecht in the Netherlands. The chasuble is now kept in the Cathedral treasury of Liege. Gone is the delightful chap sitting in the tree. And the Jerusalem street is suddenly paved. Interestingly, this chasuble was made around the same time as the chasuble of bishop Chevot. However, although now both chasubles are kept in Belgium, originally the one made for bishop David of Burgundy was made in the Northern Netherlands. Possibly in Utrecht, his bishopric see.

The Opus anglicanum piece has obviously no or nue. The orphrey made in the Southern Netherlands (bishop Chevot) has a kind of rudimentary or nue in the donkey and for the house/gate of Jerusalem. Contrary, the orphrey made in the Northern Netherlands (bishop David of Burgundy) has Jesus completely rendered in very fine or nue. Throughout the orphreys on this chasuble, Jesus is the only figure wearing clothing (partly) stitched in or nue. That's just in case an onlooker missed who was the most important figure in the embroidered story. The question remains: why is this particular scene so rare in medieval goldwork embroidery? Did embroiderers not like to stitch donkeys? They seem to do okay-ish when it comes to the Nativity. Was it a part of the Passion story that did not appeal so much to Joe Average medivialis? I do not know enough about medieval liturgy to determine if Palm Sunday was perhaps less significant back than? Or maybe other parts of the Passion were just more popular and appealed more? Trying to get into the heads of people who lived more than 700 years ago is fun, but never quite satisfactory! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed