|

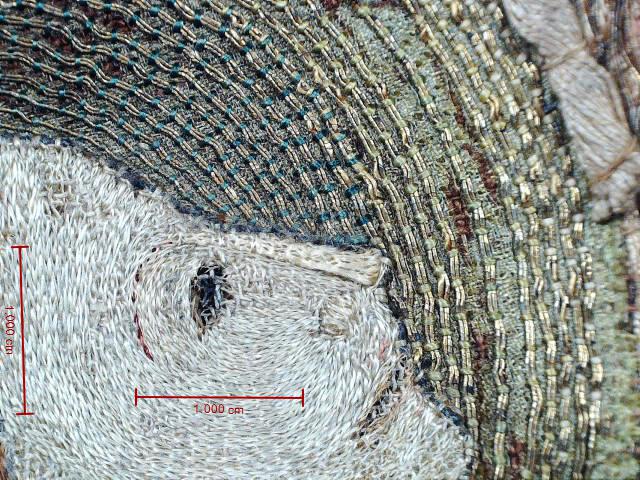

Last week's beautiful Bohemian chasuble cross was a bit large to discuss in a single blog post. And it turned out to be even more interesting. So here is part II. On a personal note: I rarely display the crucifixion scene prominently on my blog. Just like the early Christians I see an execution. However, this particular crucifixion has such beautiful embroidery and such an interesting alteration story to tell that it would be a shame not to show it to you. And there is a mystery padding technique I hope you might be able to identify. But above all, it prominently displays my favourite biblical power woman: Miriam of Magdala. Unlike Yeshua's male companions, Miriam of Magdala did not cowardly flee but endured watching Yeshua's execution. Her grief of losing her best friend is beautifully captured in this Bohemian embroidery. As is often the case in Central Europe, Miriam kneels and embraces the wooden column of the cross. She is all alone. Emphasising the special bond between Yeshua and her. Not an adultress (that's an invention by Pope Gregory I and was revised by Pope Paul VI) but a primary witness of the life and death of Yeshua. The very fine split stitch embroidery on the body of Yeshua has degraded to such an extent that the beautiful underdrawing has become visible. It is more than a simple line drawing and also shows shadows and many anatomical details. There is a red dye (probably madder) under the halo and on the beams of the cross (but avoiding the left arm). Clearly the work of a pro. The figure of Yeshua was worked as a slip and couched over the voided area of the sunny spiral background. You can see a gap between the top of the halo and that background. The halo has been elaborately padded with different shapes of parchment. If you look closely, you can also spot some later repairs. There are newer silk stitches in the crown of thorns, the hair and around the outline of the cross. You can even spot some newer goldthread under the right arm (left side of the picture). Also, the crude couching stitches visible on the right (left side of the body) are not original. And here is another detail. See the vertical line in the middle above the arm? That's a seam. Two different pieces of linen were joined here. The linen on the left is a bit finer than the linen on the right. It looks like a seam on both pieces was turned under and then the two pieces were slip stitched together. This seam was not visible when the embroidery was new. Because, if you look closely along the edge of the beam of the cross you can spot the remnants of a golden coloured fabric (probably silk). The order of work seems to have been to draw the cross on the linen background (pieced together from at least two pieces of linen) with ink and/or charcoal. Red paint was added to the beams of the cross. Then the golden background was stitched. Then the silk was appliqued over the beams of the cross and embroidered over (where the seam is, the silk of the beam lays on top of the spirals to straighten the beam and correct the line drawing). Then the figure was stitched to the background. Again, the red line along the beam and the blood splatters are later additions. The red of these later additions is much brighter than the original red silk used to edge the vertical beam (to the right of the halo). And here is the figure of Miriam of Magdala. For the most part, she is worked as a slip too. However, to get the perspective right, the last part of her right forearm is worked directly on the linen background of the sunny spirals. It even looks like there is a partial sunny spiral below the silken split stitches. It seems the embroiderer changed the design when the slip was attached. The colours are a little off too and the stitching isn't as neat as that of the rest of the arm. What is going on here? Here is another detail of the figure of Miriam of Magdala. As with the cross, there is a piece of green silk attached behind her halo. But something isn't quite right. The figure is appliqued onto the halo. The green silk is backed with a piece of coarse linen dyed a dark brown. It is not the same linen as seen behind the sunny spirals. The halo was thus not directly stitched onto the background linen on which the sunny spirals were stitched. And look at the gold thread. The gold thread in the halo (and that running along the seam of the headdress and the garment) is much shinier and hasn't oxidized in the same way as the gold thread of the sunny spirals. This is an indication that the thread in the halo is of a later date than that of the background. The thick crude white string at the top part of the halo would have been the padding for pearls. This again seems a later addition. And what about the broad padded seam along the edge of the headdress? What is it? How was it made? It seems to be stitched on top of the fine split stitches and could thus be a later addition as well. Do you recognise the technique? If so, please leave a comment below! And then there is her nose! When I first saw this, I was reminded of the parchment padded noses sometimes seen in Opus anglicanum (for instance: V&A 28A-1892). However, could it be that Miriam's nose was instead damaged at some point? The stitches are a little different and the colour of the silk seems a bit off too. The repair might account for the padded effect seen today. So. What the flip is going on? Well, I think that this beautiful Bohemian embroidery was taken apart when the current chasuble (or possibly an older predecessor with the same cut) was constructed. You see, when the original chasuble cross was stitched around AD 1380 the form of the chasuble it would have been appliqued onto was very different. It was much larger. Chasubles before the 13th-century were voluminous bell chasubles. Due to changes in the liturgy (elevation of the host) the priest needed more arm room and the chasuble became increasingly smaller. This eventually lead to the minimalist violin case shape of this 19th-century chasuble. This meant that older embroideries were too large and needed to be adapted. Often, they were simply cut off with little regard for the embroidered scenes.

Not so in this case. It seems that the figures were carefully taken off the sunny spiral background. The crucifixion cross was probably remodelled (cross beams and column shortened) and the silk was added. Miriam was given a new halo. She would have originally sat further down the column of the cross. When she had to be moved up, she either never had a halo or the halo could not be moved because it was part of the background (now possibly beneath her clothes). Due to the now shortened 'canvas' the pelican was moved down and now sits almost on top of Yeshua's halo. The figure of Yeshua is probably not quite in its original place either. A patch of newer gold thread next to his feet (big toe right foot) shows that originally something else was going on here. Maybe all the additional silk embroidery dates from this major remodelling too. All in all, it shows that this beautiful embroidery was valued and got a second lease of life. Literature Stolleis, K., 2001. Messgewänder aus deutschen Kirchenschätzen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Regensburg, Schnell & Steiner. Wenzel, K., 2016. Görlitzer Kasel. In: J. Fajt & M. Hörsch (eds.), Kaiser Karl IV, 1316-2016. Ausstellungskatalog. Nationalgalerie in Prag, p. 505-508.

6 Comments

A couple of weeks ago, I was fortunate to visit the Museum in Görlitz to study their medieval goldwork embroidery. You can read my first blog article on a 15th-century chasuble with scenes from the Life of Mary here. Today we will have a look at a very special chasuble cross made at the end of the 14th-century in a royal workshop in Bohemia. Görlitz belonged to the kingdom of Bohemia during this time. It was an important trading city that controlled the trade with woad and woollen cloth. No wonder such a high-quality chasuble cross has survived in the treasury of Saint Peter's church. Bohemian goldwork embroidery flourished in the late 14th- and early 15th-century under the patronage of the Bohemian kings. They were of the House of Luxembourg. Bohemian embroidery is quite distinctive and once you know what it looks like you can easily link other pieces. Not many pieces have survived and I don't think all of them have been published in a cohesive overview. The chasuble cross in the Museum in Görlitz is one of the lesser-known pieces. The red chasuble the Bohemian cross is mounted on is of a younger date (as is the embroidered cross mounted on the front). This shows that this piece of embroidery was still highly valued hundreds of years after it was originally made. Although the embroidered design is a classical one, I don't think that there is another Crucifixion scene with Mary Magdalene embracing the cross and with a pelican's nest above the cross within the corpus of Bohemian embroidery. Now let's have a detailed look at the embroidery by picking (plucking?) the pelican apart. The pelican and her three young are stitched in coloured silks. The split stitches used are very fine and follow the contours of the birds. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? This is a very similar technique as seen in contemporary Opus anglicanum. However, the background consists of these golden spirals that have been couched down with normal surface couching. Underside couching is absent from Bohemian embroidery. Another peculiarity of at least some of the Bohemian embroideries seems to be that these background patterns, be them spirals or diaper, are drawn onto the fabric. In this case, each spiral with its 'rays' has been individually drawn onto the fabric. Here you can see that the embroidery was worked onto two layers of linen: a very fine linen (c. 53 ct) backed by a coarser linen. Another piece of linen seen at the bottom left is from a later repair. The pelican and nest were worked as a slip and then sewn onto the chasuble cross. Here you see the later repair as a whole. Aparently, the area between the adult bird and the chicks had completely worn away at some point. It was repaired with a piece of linen and then embroidered over. The stitches are much larger and the red silk is of a different colour than the original red silk used (see blood splatters on the head of the chick on the left). And then there is the nest. It is padded with small strips of parchment. The gold threads are couched on either side of each strip in a technique known as gimped couching. By changing both the direction of the parchment strips and the gold threads, you get the illusion of a woven nest. When you look carefully, you can sometimes spot the little holes in the strips of parchment that were used to sew them onto the linen background fabric. I am also wondering what the dark-yellow substance is on the parchment. Is it paint so that the stark white colour of the parchment would not shine through? Or is it yellowed glue? This would probably help to fixate the gold threads whilst you are working. As far as I know, none of the art historians who studied the Bohemian embroideries has ever noticed the similarities with Opus anglicanum. Although underside couching is absent from the Bohemian pieces, the very fine split stitch following the contours of the figures is indeed very similar. Are there any links between Bohemia and England at the end of the 14th- and the start of the 15th-century? Yes. The House of Luxembourg. King Richard II was married to Anne of Bohemia (AD 1366-1394) in AD 1382. Anne was a sister of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg (1368-1437), who was also King of Bohemia and Hungary. Prior to her marriage, she lived in Prague castle. In addition, the mother-in-law of Henry IV was Jacquetta of Luxembourg (AD 1415/16-1472). Her family had been living in England for a couple of generations. She was also a fourth cousin twice removed from Sigismund of Luxembourg. As the earliest preserved pieces made in England are about 100 years older (MET 17.190.186) than the earliest preserved pieces of Bohemian embroidery (V&A 1375-1864), it seems possible that the technique travelled from England to Bohemia in the second half of the 14th-century. Clearly, additional research is necessary to shed some more light on this tantalizing possibility.

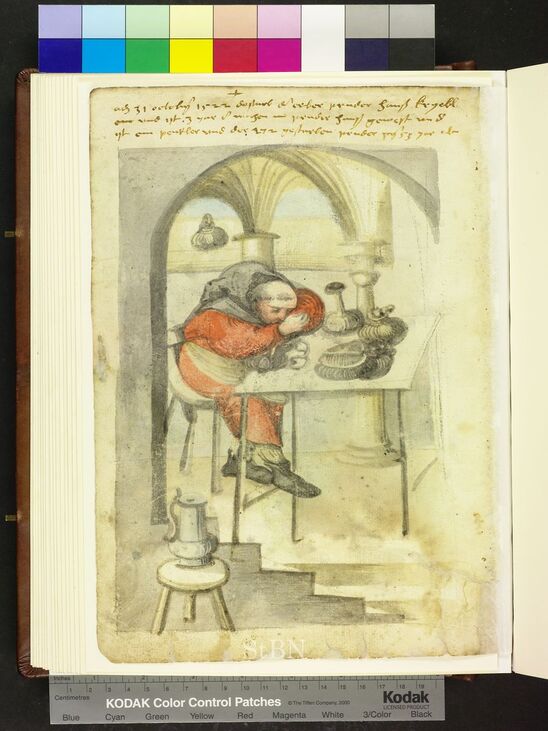

Literatur Browne, C., Davies, G., Michael, M.A. (Eds.), 2016. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press, New Haven. Wetter, E., 1999. Böhmische Bildstickerei um 1400. Die Stiftungen in Trient, Brandenburg und Danzig. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin. Duh! Of course, you can. After all, most of us have adequate heating and lighting in our modern homes. But what happens when that is not around? With the return of winter here in the Alps coinciding with the start of the museum season, the above question became suddenly relevant. As the climate is not very warm in Northern Europe, you do wonder if the production of high-quality goldwork orphreys was a year-round activity in the late medieval period. In addition, the amount of daylight would have been another prohibiting factor. The regulations of the embroiderers of Paris from AD 1292 expressly forbid stitching by candlelight. This is one of the reasons why I wanted to become a volunteer at the Glentleiten Open Air Museum. So let me tell you a bit more about the building I am working in, the embroidery I am working on and my clothing plans for the future. Although we are blessed with a lot of old stuff here in Europe, you will probably not find a preserved home from the 1500-1550s complete with its original furniture. Although Glentleiten has houses built in 1482, 1508 and 1555, these have all been 'dressed' according to a much later date. Remember, these were people's homes until quite recently! And naturally many updates happened during the past 500 years. So, I am using a house built in 1637/38, but with a reconstructed interior from 1700. Still at least 150 years too young, but it will need to do. The house is named after one of the families that used to live there: Zehentmaier. The 'maier' bit of the name hints at the fact that these were farmers and the building was indeed used as a farm. Today, the ground floor houses the modern pottery, the old living room (which I use) and the old kitchen (interestingly situated in the hallway). There is also an upstairs with additional small rooms. The above picture shows you the reconstructed kitchen. Cooking was done on an open fire. There is no real chimney. A fire-proof hood collects the smoke and leads it out through the attic and out into the open. Behind the modern iron gate in the middle of the picture, is the old living room (it can be closed off from the kitchen by a wooden door). You can see one of the small glazed windows at the far end. Just at the left rim of this picture is the entrance door. And there is a further entrance door on the right (not visible in this picture). The kitchen literally occupies part of the hallway and could easily be opened up by opening the doors. This undoubtedly helped with the fumes from the open fire. As you can see, it is all very basic and would probably not differ much from how many people lived in 1500-1550 (the first half of the 16th-century). Here you see a picture of the old living room. It has four small glazed windows (there is another one just outside the picture on the left). Back in the first half of the 16th-century, there would likely not have been glass. They would either have been open to the elements (with shutters) or they would have had oiled parchment as a covering. This produces a milky light. On a bright day, the light in the corner where the table stands, is fine for doing goldwork embroidery. However, what you can't see in this picture: the wall is made of wooden planks. The wooden planks have gaps... You are protected from the worst of the elements, but that is it. You cannot stitch here when the temperatures drop. And this is me, last November, in my current stitching spot: in front of the oven. When the museum knows that I am coming, they fire her up three days (!) in advance. She is not fired through the night because of the danger of fire breaking out (remember: there is no real chimney). Yesterday, the outside temperature was quite a bit lower than it was in November. When you come into the room, it feels quite nice. However, you start to cool out after about 30 minutes and you have a hard time getting warm again. By about three o'clock, you are getting comfortable again. The oven has then been burning for hours and it is about the warmest outside too. So, if you would be able to safely fire her through the night, you could embroider more comfortably. For the record: I was wearing jeans over thick tights, thick woollen socks, my walking boots, two t-shirts, a woollen Norwegian cardigan and a large woollen shawl! And underwear for those who wonder. At the moment, I am having a set of medieval replica clothes made and it will be interesting to see how they compare. By the way: I am still feeling quite stiff from having worked for a couple of hours in this quite cool environment. But then there is the small, but somewhat important issue of lighting. The above picture is taken with flash. Back in November with its gloomy light, I had to use two lamps to work and be able to show visitors what I am doing. That's how gloomy the light can be in this room. This was definitely not the spot where an embroiderer could have been working in the first half of the 16th-century. Could the embroiderer have alternated between the spot in front of the window and then walk over to the oven to warm up? Theoretically, yes. However, for good embroidery, you need to get into a rhythm. That would have been difficult as you cool out quite quickly and you tend to warm up slowly. So, what was the solution? Where and when did people embroider back in the late medieval period? There is a lovely resource that depicts retired medieval craftsman going about their business: Die Hausbücher der Nürenberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen. And although there is no medieval embroiderer depicted, there are other textile related crafts that probably give a good indication of how a contemporary embroiderer would have worked. Spoiler alert: it is going to be drafty. - Heinrich Sibenburger, the cloth shearer, entered the almshouse in 1555. Heinrich works in front of an open window. - a cloth maker who works outside. - as does the dyer. - A weaver from the early 15th-century, there is only one 'glazed' window, the rest is open and he seems bare-legged. - Another cloth shearer with small open windows in the background. - This person combs wool in a rather open workshop around 1500. - Otto is sitting outside in the late 15th-century to make cords. - Hans is clearly struggling to see the sewing on the purse he is making in the early 16th-century. - At around the same time, another Hans works his purses in the door opening. It is unfortunate that the older depictions in the Hausbücher don't show any of the architecture. Pictures from after the middle of the 16th-century show increasingly larger glazed windows. Lots of very interested visitors and the cold made for very little progress on the or nue figure of St Nicholas. Are my experiences and observations comparable to that of a medieval embroiderer? To a certain extent. My medieval counterpart was likely a man. Typically, men have more muscle tissue than women do and this wonderful stuff generates heat. That's why men in general have fewer issues with being cold than women do.

Were medieval people just made of hardier stock than me? Yup. As a Westerner born in the last quarter of the 20th-century, I have had central heating at my disposal for most of my life (with a brief interruption when I was living in England: I was cold all the time. Older night-storage heaters are a crime against humanity.). And although we do not heat excessively, but put on a cardigan instead, I do not doubt that it is much more comfortable than it was in the medieval period. Periodically, I will update you on my work in Glentleiten. It will be particularly interesting to see how my replica clothing holds up. And at what point I can actually move into the doorway or even completely outside with my stitching. Do come by to visit me if you can! You can find all the future data here. Hope to see many of you at Glentleiten this year! |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed