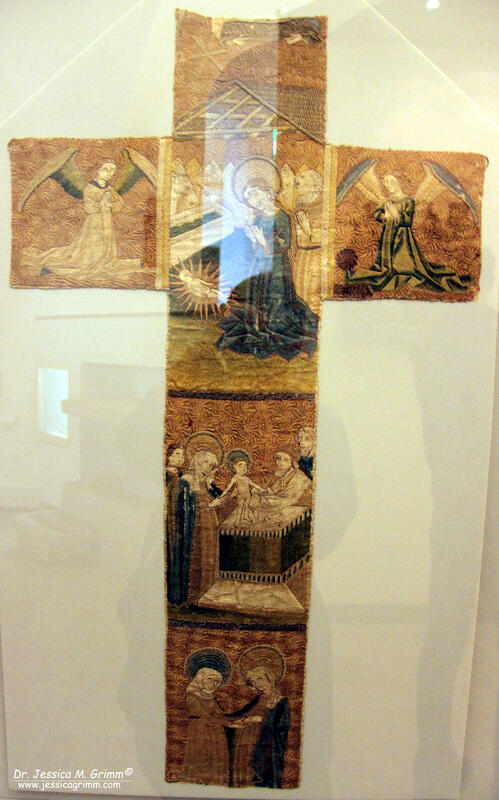

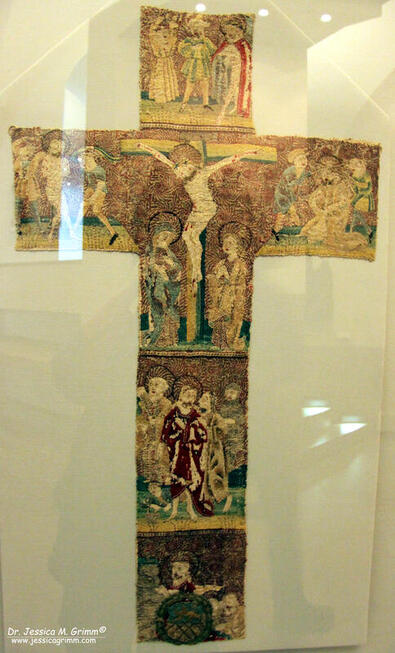

Gold threads and paintings in silk: Velvets and embroidery from the Gothic era and the Renaissance30/9/2019 Last week I was finally able to visit this magnificent embroidery exhibition in the Castello Buonconsiglio in Trento, Italy. It is on until the third of November and I urge you to visit if at all possible as it is as important as the Dutch exhibition in Utrecht in 2015 or the Opus Anglicanum exhibition in London in 2016. And yes there is a wonderful catalogue, but just as the Dutch did, the Italians thought it a brilliant idea to publish the scientific papers on these extraordinary pieces in their own language. At 423 pages, it will take me aeons to translate ... However, it is packed full with stunning pictures of the embroidery. Including many close-ups. Together with the 400+ pictures I took during my three-hour visit, it will be a treasure trove for years to come! You will hopefully understand that I can't publish all the 400+ pictures in this one blog post. Instead, I will concentrate on three (well actually four) extraordinary pieces that were on display. First up is a chasuble made in the middle of the 15th century in Venice. Why did I pick this particular one to show you? If you are used to the orphreys from the Low Countries, these Venetian examples look very different. They show the same main principle: saint in front of some fancy architecture. But the embroidery techniques used are somewhat different. The examples from the Low Countries use much more gold thread for the architectural backgrounds. And their linen background is fully covered with embroidery. Not so in this piece: the background is stitched on green silk. They look airy and light; a typical sign of the art of the Renaissance. The examples from the Low Countries are in comparison much stiffer and heavy. The figures themselves are also embroidered in a different way than the majority of the pieces from the Low Countries. As in the Low Countries, the figures are embroidered onto a linen base. However, the embroidery technique used is a form of shaded laid-work using untwisted coloured silk for the undergarments. Simple couching of pairs of fine passing thread for the cloak and fine silk shading for the faces and hands. The figures in the orphreys from the Low Countries are mainly done in splendid or nue. Unfortunately, the stiffness of the linen base in comparison to the lightness of the green silk makes the piece pucker. Not easy to photograph! Most incredibly, this chasuble is still worn every 3rd of May on the feast of the Apostles Philip and James! Next up is an example of a chasuble which fascinates me hugely. This is serious stumpwork made at the start of the 16th century somewhere in the German-speaking parts of Central Europe. You come across this type regularly in this part of the world (there are in fact two more in the exhibition), but this is an exceptionally stunning piece with highly sculptured figures. The faces are incredible! And look at Jesus's curly hair. A theory put forward by Aleth Lorne (2015, p. 99-102) to explain these highly sculptural pieces is that the embroiderers and the woodcarvers in the German-speaking parts of Central Europe influenced each other in their search for the three-dimensional rendition of the world. Both craftsmen were often part of the same guild and probably used the same designs made by yet another craftsman. These pieces were so well-known that they are recognisably depicted on paintings from the same period, but not necessarily from the same area. People were clearly fascinated by these pieces. Particularly good examples further adorned with thousands of fresh-water pearls can be seen in the treasury of the Basilica of Mariazell in Austria. There is just one thing about this chasuble which I do not understand. See the bottom? Someone brutally cut through Saint Joachim when the taste in chasuble shapes changed from wide to a violin-case. This probably happened in the 17th century (Stolleis 2001, p. 29). I hope the scissors wore out :). And last but not least, I am going to show you two dalmatics (vestments worn by the deacon) made in the Netherlands at the start of the 16th century. These new acquisitions by the museum lead to this exquisite exhibition. They are displayed in the last room together with three other chasubles. And the best thing is: they are not behind glass! You can get up close and personal with them :). The orphreys on these dalmatics are of the typical type seen on vestments from the Low Countries from this era (you now clearly see the difference with the first chasuble I showed you which was made in Venice). Completely covered in embroidery and featuring beautiful or nue on the figures. The pieces are quite similar to the vestments made for David of Burgundy, bishop of Utrecht in the 15th century. They are in fact so similar that I for a moment thought that they were the ones made for David.

The vestments made for David were probably embroidered by an atelier in Utrecht. These slightly later dalmatics could either be embroidered in Amsterdam or indeed Utrecht. I got the giggles when I saw that the museum Castello Bonconsiglio thinks that Amsterdam and Utrecht are situated in Flanders. Not quite. But close :). Sources: Dal Pra, L., M. Carmignani & P. Peri (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Castello del Buonconsiglio. Lorne, A. (2015): Borduurwerkers en beeldhouwers in de Nederlanden en het Rijnland in de late Middeleeuwen. In: M. Leeflang & K. van Schooten, Middeleeuwse borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden, Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht, pp. 95-103. Stoleis, K. (2001): Messgewänder aus deutschen Kirchenschätzen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Regensburg. P.S. If you like what you see, please consider making a donation using the PayPal button in the right-side column. Hugely appreciated!

6 Comments

There are quite a few embroidery exhibitions going on at the moment or coming up in the near future. As I am going to all of these (in the name of CPD!), you will all have the opportunity to read about them on this blog. However, with this advance notice, some of you might be able to go an visit yourselves! First up is an embroidery exhibition in Trient, Italy. Until the third of November, 40 vestments from all over Northern Italy and dating to the second half of the 15th to the first decades of the 16th century are shown in the Castello del Buonconsiglio. There is also a catalogue available. As some were specially restored for this exhibition, it is surely going to be a treat! From the 24th of October till the 20th of January 2020, there is an exhibition on medieval embroidery on at the Museum Cluny in Paris. You can find the general press release here and a full list of high-lights with pictures here. And last but not least: our 'own' exhibition in London from the 12th till 17th November! My piece of Pope Francis will be joined by many, many amazing pieces from a great number of contemporary embroidery artists from all over the world. An opportunity not to be missed!

Weeks ago I saw mention of an embroidery exhibition in Paris on Social Media. After finding out that there is a direct train between Munich and Paris, I decided to go. As the exhibition was soon to end, I did not have the luxury of being choosy when to go or for how long. I and my husband ended up going for 48 hours to a very, very hot Paris. Although I have experienced 40+ degrees before when staying in the deserts of Egypt and Lybia, I hope to never experience Paris in 43,2 degrees ever again! Luckily, the Louvre has cool air vents in most of its stone-paved floors. Guess who walked barefoot during her nine-hour visit? So, what was it all about? The Louvre housed a small, but spectacular goldwork embroidery exhibition in room 505. The pieces dated from the 15th to the 17th century and were made in modern-day Romania. And it turned out to contain some of the largest and most opulent goldwork embroideries I have ever seen! But let's start with the bulk of the embroideries. Romanian or better Wallachian and Moldavian embroidery of the late Middle Ages and early Modern Times is closely related with the Orthodox Church. On display were Orthodox vestments such as: epitrachelion (stole), epimanikia (cufs), epigonation (badge) and epithaphios (an embroidered icon bearing the dead body of Christ). When the Byzantine Empire ceased to exist in AD 1453, the Orthodox Church becomes the keeper of the Greek liturgical culture. The voivodes (princes) of Wallachia and Moldavia see themselves as the heirs and protectors of this heritage. They make donations to monasteries in their own realms, but also to those on Mount Athos in Greece. And some pieces even end up in Jerusalem. Embroidery of this kind was supervised and practised by noblewomen at the court in Byzantium and later at the courts of the voivodes. Both within the noble household as well as in specialised workshops. There is some historical evidence that talented professional embroidery workers were bought free from the Ottomans and they then relocated to Wallachia or Moldavia. However, some of the embroidery workers were serfs. Equally, noblewomen from the Balkans married into the royal families of Wallachia and Moldova. Taking with them and preserving Byzantine embroidery techniques and styles. Due to the conservative nature of Orthodox iconography, it is often impossible to tell where pieces were made or by whom. However, most pieces bear the initials or full names of the donors (abbots, princes, princesses and other nobility). Certain patterns were often even faithfully copied over centuries. Apart from the vestments, there were burial shrouds on display. These huge goldwork embroideries display the edifice of the deceased ruler, his wife or their offspring. The oldest one on display was made for Maria of Mangup before AD 1477 and measures a staggering 191 x 103 cm! Nearly 150 years later, these funerary portraits become even bigger and far more opulent. The goldwork embroidery on them is amazing. Although the exhibition was centred around the banner of Stephen the Great (died AD 1504), I found the piece rather underwhelming compared to the other pieces on display. It measures 124 x 94 cm and shows St. George sitting comfy on a throne resting his feet on a dragon. The figure of St. George is entirely formed of couched silver and gilt threads. Due to the use of conservation net on the whole piece (and indeed many other pieces on display) it was rather difficult to see the actual stitching. This was further complicated by the very low levels of lighting and the dirty glass on the display cases. For those of you interested in this type of embroidery, the Louvre sells an excellent catalogue. Each piece is beautifully photographed and there are even some detail pictures. The book further contains chapters on the political situation of the area during the late Middle Ages, on the historical context of the embroideries, on the banner of Stephen, on the vestments and on the funerary shrouds. As I can only read French with great difficulty, I translated the chapter on the historical context into English. And I am also working on the other chapters and the catalogue part. However, what the book lacks is a chapter on the 'how'. What embroidery techniques were used? What materials were used? It, unfortunately, does not go beyond metal threads and polychrome silk on a velvet background. Do 'how to' books on this type of goldwork embroidery exist? I would love to hear if you know of one! At least a little bit of the 'how' was captured in some of the pictures I took. Here you see a glimpse of the padding underneath the gold threads forming the halo. It really is quite different from the way we do things in western-style goldwork embroidery. I would love to learn more ...

After a successful vernissage and first exhibition weekend, I am a very happy (but incredibly tired!) embroidery artist. It all started in earnest last Thursday with me carefully packing all my embroideries and with my husband puzzling hard to make it all fit into our little red car. We left right after breakfast on Friday morning and drove the 30 minutes to the Dorfmuseum in Roßhaupten. In the meantime, I had seen the first newspaper article on my upcoming vernissage and exhibition. I and my husband unloaded the car and started to unwrap all my embroideries. As my exhibition is hosted in two very large and beautiful rooms at the museum, I decided to place the pieces along all walls before actually hanging them. My nearly 10 years of art embroidery were barely enough to fill the two rooms! But before we could actually start hanging the pieces, the people of Allgäu TV arrived for an interview in front of the camera. Little did I knew that 'in front of the camera' indeed means that the machine sits just inches away from your face. Pretty uncomfortable. And so weird to see myself on film! Here is a link to the video. The interview with me is in the last five minutes. I am so pleased they really took the time to introduce my latest piece 'On the shores of St. Nick'. I was also able to address the whole 'I am officially not an artist' issue. Unfortunately, they did get their embroidery techniques quite wrong :). During the filming, my husband kept hanging my embroideries: He did a great job! As things always take longer than you think, the organiser of the art exhibitions cooked us an excellent lunch. After that, we returned home for a short nap and some much-needed freshening-up before the vernissage later that day. There were about 25 people attending my vernissage and my speech was very well received. I was able to point out my difficulties with being recognised as an artist and the whole craft versus art debate. As there were several journalists among the attendees, this point will certainly get some attention. And I was especially pleased to see five people from Bad Bayersoien attending, as well as my sister-in-law with husband and youngest son, my framer and his wife and Petra from the eco-store I love to shop at. And then ... it happened ... I sold my first piece !!! So incredibly grateful. I had such lovely chats with my visitors. They were all so impressed by my work. They had never seen anything like it. And more than one told me that my pieces are so beautiful that they made them feel happy. What a lovely compliment. During the next two days, the exhibition was open between 15-18 hours. Quite a few people came through the door. Tourists and locals in equal measures. And some even came both days and brought more family and friends along. How cool is that?!

And then ... it happened again ... I sold two more pieces! Still doing a happy dance :). And with two more weekends to come, I am pretty confident that I will sell some more pieces. But first I am hoping for a few long nights in order to lose the bags under my eyes ... I am getting really excited as the vernissage of my first-ever solo-exhibition draws nearer! As this is my first time organising and promoting such an event myself, I really do hope I have managed to think of everything :). Apart from sending invitations to important people, gallery owners and friends; I and my husband also spent two days dropping them in every mailbox in our village. The only things left: hanging the exhibition posters around the village for the tourists to see, signing the insurance papers, preparing my speech and hanging the exhibition. So cool! But that's not all that has been happening in my embroidery life! Last week, I taught crewel embroidery to Kristin from Berlin and Elena from Switzerland. As the three of us were born in the 70s, love to travel, have no kids, love our men (but think they are a rather peculiar species), we had a lot of fun! And cake, of course. Oh, and we stitched too :). Kristin chose an image from one of these generic pattern books you can find in most bookshops. You can use these patterns for a variety of crafts and they are an especially good starting point for embroidery. Picking colours from the full range of Heathway Milano super-quality crewel wool was a true Qual der Wahl (the agony of choice). But she chose well in combining Pomegranate with Laurel and a dash of Daffodil! Kristin really wanted to incorporate lots of colours and even some pearls. Way out of her comfort zone, but working so well! I can't wait to see this piece getting finished. Elena has been working the same image for years. Don't get me wrong, she isn't slow or anything, but she works the same image in different techniques :). As a base, she uses a Russian translation of the RSN-embroidery book. So far she has worked two beautiful irises: one in goldwork and one in blackwork. It was now time to tackle the crewelwork one! Beautiful Heathway Milano Violet and Gobelin Green were the perfect colours for the job. As the original piece in the book is made with variegated threads, we also added some hand-dyed raw silk by House of Embroidery. The fluffy nature of the wool combines very well with the spun silk. And of course, we added some sparkly pearls as well. As Elena really liked working with the wool and filling areas with trellis stitch, I am hoping for a speedy finish :).

That's all for now! I hope to see at least some of you during the vernissage or the opening hours of the exhibition. All my work will be on display and I will be present during the opening hours. The National Silk Museum in Hangzhou had a small number of embroideries made by several ethnic minorities on display. After last week's book review on the textile traditions of one of these minorities, the Miao (Hmong), I thought it a good idea to share my pictures with you! First up is an embroidered apron worn by women of the Dong minority. The Dong are matrilinear people from the south of China. The embroidery on this apron consists of brightly coloured satin stitches (possibly over a cut paper template) and some applique. The pattern is made up of stylised flowers and the sun symbol (probably the swirls; Chinese explanations at museums are notoriously vague ...). Other parts of the apron consist of strips of wax-resist dyeing. Unfortunately, the only thing stated on this apron is that it was worn by an ethnic minority from Guizhou province. What I understand from the museum's description is that this is a single panel and that several of these embroidered panels would make up the actual apron. Do you see all these white buttonhole wheels? There are also chain stitches and knots. I think they used chain stitches to create the star shapes on the left and the maple leaves on the far right. Quite a clever and visually pleasing piece, I think! This panel was embroidered by the Ge people who also live in Guizhou province and who are officially considered to be a sub-group within the Miao. This piece mainly consists of outlines stitched with fine and very regular chain stitches. There is also some back stitch and some satin stitch visible. This piece of clothing (called 'braces' in the description) was also embroidered by the Ge people. It is again covered with very regular chain stitches and interspersed with satin stitches. The regularity of both pattern and stitching is absolutely stunning! The last piece on display was an embroidered shawl made by the Miao. The geometric pattern is based on an old song and represents flower beds. The stitching is entirely done in a form of long-armed cross-stitch. This is even a better close-up of the flower bed pattern. The movement created with the stitching is absolutely sublime! Keep staring at it and see how many different patterns you are able to see :).

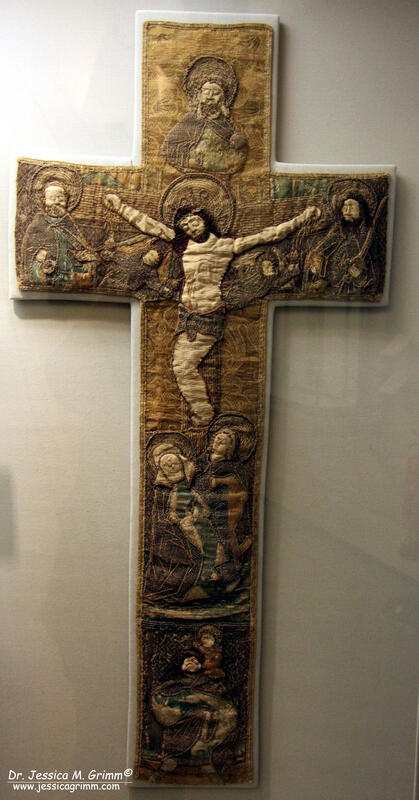

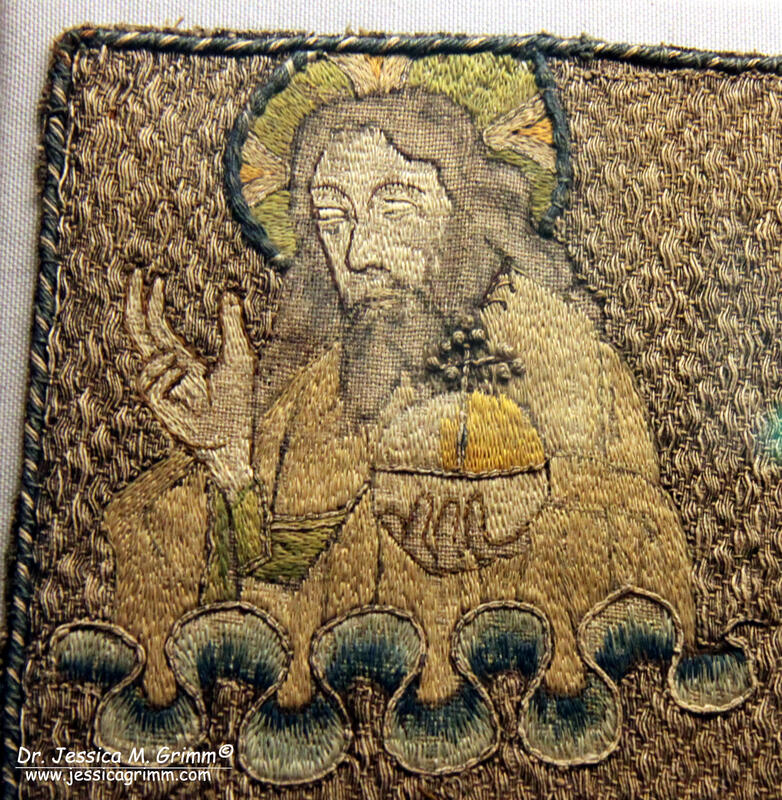

Last week, I showed you the vestments from the 17th and 18th century on display at the Dommuseum in Fulda. This week we will have a look at the medieval ones. Although the lighting was much better in this part of the exhibition, the glass of the showcases posed a huge problem when photographing the pieces. And to make matters worse, the warden revoked my permission to photograph. Nevertheless, I have a hand-full of nice pictures of very high-end goldwork and silk embroidery to share with you! First up are two pictures of an embroidered cross which would have adorned a chasuble. These embroideries were so precious, that they were mostly re-used on a new vestment when the old one was worn. In this case, the embroidery is a little special: it is raised embroidery. We often associate stumpwork embroidery with 17th-century England. In this case, however, the embroidery was done around 1500. The exact provenance was not stated, but these stumpwork embroideries were all made in the German-speaking parts of Europe. The most exquisite examples can be found in Mariazell, Austria. Here the figures stand about 3 cm proud of the background fabric! In the detail picture above, one can clearly see that the faces of both Peter and Jesus are padded. Jesus's ribcage is defined with a piece of string padding. The whole figure of Jesus seems to be somewhat padded. And the flesh-coloured fabric looks quite stiff and a bit like paper or vellum. And here we have two depictures of God from two different late-medieval chasuble crosses. Unfortunately, no further information was displayed for these two. Or maybe I forgot to take a picture ... I quite like these two. The clouds remind me somewhat of Chinese embroidery on the imperial Dragon Robes. Last up are these two. They are chasuble crosses embroidered around 1480. No provenance is given. These two caught my eye as the embroidery techniques used are quite different from the other vestments on display. No or nue here; the figures are stitched in silk using long-and-short stitch. In this detail shot, you can see what I mean. No or nue for the figures here. Instead, there is meticulous tapestry shading on the clothing (i.e. silk shading strict vertically instead of naturally). And the couching patterns for the goldwork threads in the background are so full of movement and quite different from the strict geometrical patterns seen in the late-medieval vestments from the Low Countries. I had a strange feeling that I had seen this before. And luckily for me, my mind sometimes does a good job :). Instead of needing to go through my thousands of pictures taken at museums, I knew at which museum I had seen this: the Diözesanmuseum Brixen, Italy. This late-15th-century (same date as the one from Fulda!) chasuble cross has a similar couched background. And most of the figures are stitched in tapestry shading rather than or nue (Mary being a notable exemption). So maybe the chasuble cross held at the Dommuseum Fulda has a more southern origin?

Being able to make these connections only works when I am allowed to take pictures. As lighting conditions or the way things are exhibited often do not permit studying the embroidery with the naked eye, my pictures are a great help. The camera is able to pick up details even when lighting is poor. I can zoom while taking a picture and again when looking at my pictures on the computer. Applying filters will tell me even more about the way things were made. It is therefore always very sad when the taking of pictures is not permitted. As long as you do not use flash (or use another source of light such as your phone!), you are not damaging the exhibits. And me taking pictures of the exhibits as is, has other benefits too. I don't need to make an official appointment for which museum staff needs to 'host' me (they have better things to do) and I don't need to handle the exhibits either. Some museums argue that by taking photographs and publishing them in a blog or on social media will mean fewer people will actually visit the museum. Really? I have the sneaking feeling that more people will visit a museum when they know what is on show. Especially museums with a wide range of exhibits of which textiles are only a small portion. The museum's website often does not specifically state that there are gorgeous embroideries on display (they are a somewhat neglected category, especially when in competition with bling made of precious metals) which might interest the curious embroiderer. And I know that several of my readers have visited museums which featured in my blogs. I have been guilty of doing the same. Maybe we should start mentioning these things to staff on duty when visiting a museum after reading a blog or seeing a picture on social media. What do you think? A couple of weeks ago, I visited the Dommuseum in Fulda. I knew from their website that they had at least some embroidered vestments. Little did I know that they had quite a lot of them! And when I asked if I would be allowed to take pictures, the clerk on duty said that he didn't mind me taking pictures. Unfortunately, he was quite a character and rather unpleasant. Half-way through the exhibition, he told me to stop photographing. No reason was given. Lucky for you and me, I had been able to take quite a few pictures before I was told to stop :). Enjoy the bling ... The above short video was shot with my phone. What you see here is one of the rooms where the vestments are shown. There are several of these large displays. They are reserved for the 'younger' vestments dating to the Baroque and Rococo (17th and 18th century). The vestments are shown in a kind of altar setting interspersed with other liturgical objects. Sets of matching liturgical vestments (cope, chasuble and dalmatic) are grouped together. As you can see the lighting is rather sparse. And the fact that most pieces are placed at a distance from the glass wall, makes studying them almost impossible. The written information was mostly limited to the name of the vestment, the date and the person who paid for it or for whom it was made. Not ideal for the curious embroideress! That said: the dim light and the 'scenic' placement of the vestments did give a good idea of how these gold embroidered vestements would have sparkled all those centuries ago. And that is an impression not many of us get to see nowadays. After all, how likely would it be to sit in a church service in the semi-dark (safety hazard!) with enough senior clergymen present (they are thinly spread these days!) that a full set of these antique vestments (museum people in uproar!) can be worn? And this is a picture of the same display made with my Canon digital camera (no flash, just a very steady hand). On the far left, you'll see a yellow cope behind a yellow dalmatic and maniple. They belong to the so-called Harstallscher Goldornat made in 1802 for the last Prince-Bishop of Fulda Adalbert von Harstall (1737-1814). The vestments are made of silk and gold brocade with some goldwork embroidery. Prominently in the middle of the picture are some red vestments. From the left: chasuble, stola, cope, palla, bursa, pink chasuble, pink stola and dalmatic. They belong to the so-called Roter Schleiffrasornat made in 1702 for Prince-Bishop Adalbert von Schleiffras (1650-1714). It is the oldest complete set of vestments in the museum. The vestments are made of silk and heavily decorated with goldwork embroidery. Detail of the cope hood of the Roter Schleiffrasornat. And this exquisite piece of goldwork embroidery can be found on the hood of the cope belonging to the Weisser Buseckscher Ornat made in 1748 for the Prince-Bishop Amand von Buseck (1685-1756). The fact that Amand was very good at drawing and a sponsor of the arts is probably reflected in the high quality of the padded goldwork on his vestments. Amongst all the bling I discovered what looks like a 17th-century casket of some sorts. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't take decent pictures of it. And there was no information on the piece either. But since I know that there are several 'casketeers' reading my blog, I am including it here anyway.

That's quite enough bling for today me thinks! Although it is quite difficult to see the beautiful goldwork embroidery up close due to the way the pieces are presented, the museum is well worth a visit and even a detour when you are in the area. Especially as they have some even greater embroidered treasures dating to the Middle Ages. But that's for another blog post ... Last week I was fortunate enough to visit the exhibition 'The embroidered Heaven' at the Church Heritage Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania. I also met with Lithuanian embroideress Agne Zemkajute. Discussing pieces in the exhibition with a kindred soul is pure bliss! And Agne proved to be a very knowledgeable guide and fellow cake eater :). As we both have a love of church textiles and love to recreate them, this was certainly not the last time we have met. For those of you not living within two hours flying time from Vilnius, I will try to pack this blog post as full as I can with impressions of the exhibition. And at the end of this lengthy post, I will pass on details of the lovely catalogue produced by the museum. The exhibits were displayed chronologically from the Late Medieval period until the 20th century. Due to the fact that the Lithuanians were the last peoples in Europe to convert to Christianity in AD 1387, there aren't any really old vestments. And Lithuania's turbulent recent history with 100 years of Tsarist rule, two World Wars and the Soviet Occupation, didn't help in the preservation of what once has been there either. Nevertheless, there were two chasubles and a cope hood on display which dated to the Late Medieval period. One of the Late Medieval chasubles was 'restored' using paint. Its iconography of saints sitting under an architectural arch is well-known from many other embroidered vestments and paintings dating to the same period. There were many more chasubles and related vestments on display dating to the 17th century. Contrary to earlier vestments who told a biblical story, vestments from the Baroque period feature large floral motives and an excessive use of gold threads. The height of the padding on some of these pieces is mind-boggling! These vestments were meant to dazzle you and to clearly show you who held power. Although I am not a fan of the Baroque period, I do admire the skill needed to produce these magnificent pieces of highly-padded goldwork embroidery. Today, this style of embroidery is still in use in the embroidery ateliers of Spain. One of the people teaching this type of embroidery and blogging about it, is Cristina Badillo. Playful 18th century Rococo with its elegant floral motives is much more my cup of tea. Especially the cope displayed above. Does this not remind you of Jacobean crewel work? However, this is made with silk and silver passing thread. I have never come across a piece like this and I would love to hear from my readers if they know of a comparable piece. Agne and I discussed the piece at length as we can't quite discern how the flowers have been stitched. In fact, we have so many questions about this piece that we will have no choice (how horrible!) than to try and recreate some of it. Just determining if it is best to stitch the silk before the metal threads or the other way around was just not possible from looking at the piece. We even took pictures if the blown-up detail pictures on display to get a grip on the stitching process... This chasuble from c. 1909 reminds me of the chasubles made by Leo Peters, a Dutch artist, around that time. It has an Art Nouveau feel to it. And the padding underneath the figure of Jesus and the cross is just amazingly thick. And I really liked this early 20th century piece as well. I don't remember seeing vestments using panels of needlepoint before. There is even some drawn-thread work in this one.

Apart from the many embroidered vestments on display in the exhibition, the museum also has a few vestments on permanent display. And, best of all, they have a large set of drawers on the organ gallery. Each drawer contains a vestment. They allow you to browse through them and have a good look at them without the hindrance of glass! Please note: the exhibition 'The embroidered Heaven' will end on the 15th of September 2018. However, the Church Heritage Museum sells a wonderful catalogue, hard-bound, and with full-page detailed pictures of all the vestments held by the museum. Although the regular text is in Lithuanian, there is an excellent summary in English in the back. The catalogue has 222 pages and costs only €15. You can contact the museum here. As I told you in my last blog post, I rendezvoused with the medieval vestments at St. Paul im Lavanttal (Austria) last week. And what a delight it was! The weather was quite hot and thus perhaps not ideal for visiting a museum. This meant that I had the pieces to myself and could take as many pictures as I liked :). I had also brought a tiny bit of replica-stitching to compare with the original; more on that further down. Let me introduce you to the older chasuble housed at St. Paul Abbey. This chasuble dates to the reign of abbot Bertholdus who died in AD 1141. The piece is thus more than 875 years old!!! It never ceases to amaze me how well these vestments are preserved considering their age and the fragile materials they are made of. The chasuble displays scenes from the bible: seven from the New Testament and 16 from the Old Testament. These scenes are not just 'pretty' or an incidental record of certain biblical stories. Instead, the scenes from the Old testament have a theological relationship with those from the New Testament. For instance, the Annunciation is paired with the foretelling of the births of Samson and Izsak. Each of these scenes fits into a square. The scenes from the Old Testament have some writing in them as well. Perhaps while they were and are generally lesser known and/or harder to identify. Further towards the hem, 20 saints are displayed. These saints had a special relationship with the original Abbey of St. Blaise. Along the hem, 36 small roundels display, amongst others, the edifices of the twelve Apostles, St. Paul, prophets, evangelists and the founder of the Abbey: Holy Roman Emperor Otto I (AD 912-973). The priest wearing the chasuble was literally a walking theological learning aid :). And not for the 'common folk' as they would not generally attend mass in the Abbey church. Instead, the chasuble would remind the monks themselves of Christian theology and the lives of the saints. To separate each square, there are smaller squares with mostly geometrical patterns (there are birds and floral patterns displayed in the squares on the 'cross-roads'). And there are a lot of them! I have half-heartedly started to catalogue them and have already counted more than 25 different geometrical patterns. And it is one of these patterns that I started to replicate. At first I thought that the stitch used was closed herringbone. This is however not the case. A row of closed herringbone stitches produces two parallel lines of stitches on the back: back-stitch on the one and split stitch on the other. It was long hold that this was the stitch used on the chasuble. However, when I stitched my copy, I ended up with small gaps where two rows 'bud'. Upon checking the literature again, I saw that during the restauration of the piece it was found that the stitch used is in fact long-armed cross-stitch with a small compensating stitch at the start (diagram). I decided to stitch the same pattern again using DeVere 60-fold loose-twist silk on Zweigart Newcastle 40ct natural linen. And presto! No more gaps and the pattern became nice and square (it really is! pardon my photography). It is still at 41,5 mm a bit bigger than the original. This means that the linen background fabric used was finer than 40ct (!) and the silk too. What I further learned from my wee bit of replica-ing, is that the end-result becomes quite stiff. The bulk of the silk thread is on the front and adds quite a bit of weight to the finished piece.

In the future, I would like to try my hand at one of the non-geometrical scenes. After all, copying a geometrical pattern with what is in essence a geometrical stitch, is not a problem. However, I am in awe at the craftsmanship needed to execute curves and natural forms using rows of long-armed cross-stitch! To me, that makes stitching a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry (c. AD 1070) like a walk in the park :). |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed