|

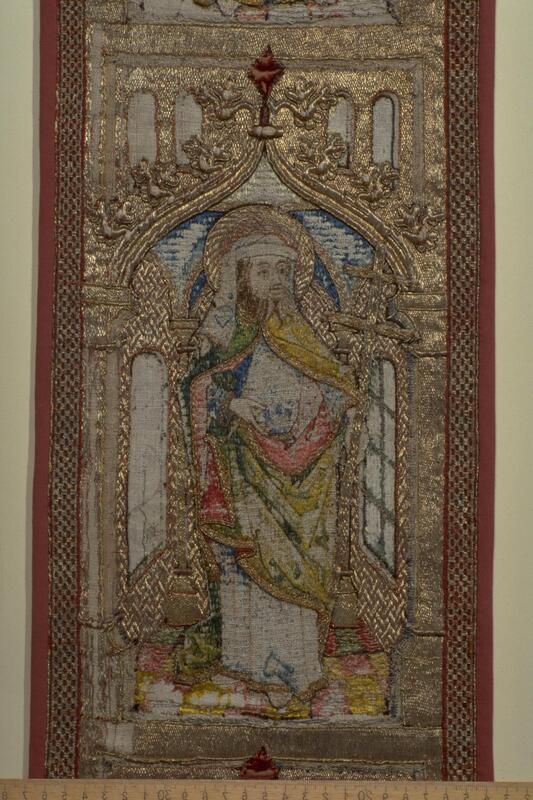

Last month, we looked at some early 15th century embroidery from Venice, Italy. You can read about it here: Cope of Pope Gregory XII, further early 15th century embroidery from Venice and a tutorial. This week, we will look at a Venetian piece from the second half of the 15th century. It has some lovely embroidery techniques that would work well for modern goldwork embroidery. And the embroidery background is a bit unusual as well. Instead of using a diaper pattern, it is made of floral motives stitched directly on coloured silk. Let's have a look! I saw the above chasuble at the exhibition in Castello del Buonconsiglio in 2019. The exhibition presented an overview of medieval goldwork embroidery made in Italy; complemented by those pieces that were obtained by trade from Northern Europe. The chasuble is kept, and still being worn once a year!, at the parish church of Azzone, near Bergamo, in the Scalve Valley. The valley came under Venetian rule in 1427 and this probably explains why this piece of Venetian embroidery can be found in Azzone. The chasuble has an embroidered orphrey cross on the front and an embroidered orphrey column on the back. As the figures on the front cannot be identified, the exhibition showed the back. Here we see John the Evangelist at the top, followed by a male martyr with a palm branch and architectural model (According to the literature it is a church. However, it looks more like a castle to me.) and the figure at the bottom is Saint Barbara with her tower. Saint Barbara is the patron saint of miners. The Scalve Valley was famous for its iron ore mines. The embroidery is executed on a layer of silk backed with linen for the background and a layer of linen for the figures. The heads were embroidered separately. The finished orphrey column was stiffened with cardboard. The orphreys measure about 33 x 12 cm. The embroidery is a rather simple, yet very effective, affair. The figures stand on a floor made with laid shaded silk and couched down with a trellis. By having the lighter colour at the front and the darkest colour at the back, the embroiderer created a sense of depth. The undergarment of the martyr is stitched in a similar way. This time, the laid silk is couched down horizontally. The cloak consists of horizontally laid pairs of gold thread which are couched down with white silk. Folds are accentuated with couched coloured silk. The heads are stitched in split stitch.

The treatment of the background behind the figures is quite special. The coloured silken background is part of the design. It is covered with the obligatory arch under which the saint stands. The background is further filled in with tendrils and floral elements. These are made by couching down a pair of gold threads and filling in some elements with shaded satin stitch. The frame around the orphrey consists of a very simple padded basket weave over two padding threads (over three is probably more common). All in all, the embroidery techniques used (laid work instead of brick stitching for the undergarments, simple monochrome couching for the cloaks instead of or nue, embroidered coloured silk for the background instead of a diaper pattern, etc.) are simple and far more speedy to execute than or nue, brick stitching and diaper couching. This likely means that these embroideries were not as expensive as the ones we investigated last month. Literature Prá, Laura Dal; Carmignani, Marina; Peri, Paolo (Eds.) (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Trento: Castello del Buonconsiglio.

1 Comment

FINALLY: three years and one month after I ordered the above title, it finally arrived a couple of days ago. It is the third (and last) volume on a research project regarding the Imperial Vestments kept in Bamberg. I have written two previous book reviews which you can find here: volume 1 and volume 2. And I have written several blogs (you can scroll through them) before about the Imperial Vestments. These are six embroidered textiles associated with Emperor Henry II and his wife Kunigunde. They date to the first quarter of the 11th century. Although none of the vestments has survived in its original shape, they are among the oldest complete gold embroidered vestments in the world. Hence, they are unique and pretty important as objects of study. This third volume was the volume I looked forward to the most as it contains the "Art technology and material science aspects" (i.e. the materials and the way they were used) of the research. Let's see if my expectations were being met. The book is divided into two main parts. The first part is written by Sibylle Ruß. She is a conservator and restorer of cultural property. She started her education at an embroidery workshop and finished with a Gesellenprüfung (Journeyman examination) before being trained at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum as a conservator and restorer. Sybille describes each vestment in great detail. Especially the different conserving and restoring measures which took place over the centuries. The original embroidery does not get nearly as much attention. This is a missed opportunity. Some things I miss: how where the gold threads being turned? Are the gold threads plunged or just secured on the front with a few extra couching stitches? What are the stitch lengths of the stem stitches? A huge amount of raw data has been collected for this research. There are tantalising glimpses of this data in the form of drawings of the individual design elements with their gold thread directions and couching patterns. I would have loved a CD with this additional information accompanying the book. I am also missing digital reconstructions of the original embroideries. This has been done for some other medieval goldwork embroideries (most notably the Hungarian Coronation Mantle, which is related to these Imperial Vestments). Some of the embroidery is in such bad shape that a digital reconstruction would have really helped to point out how splendid they once were. The second part of the book is written by Ursula Drewello. She works at the Laboratory Drewello and Weißmann and was responsible for the material science part of the research project. The dyestuff analysis was done by Ina Vanden Berghe of KIK-IRPA the Royal Institute of Cultural Heritage in Belgium. Reading about the exact composition of the gold threads, the angle of wrapping the gold foil around the silken core, the dye used for the silken core, etc., was really nice. But I am missing something here too: how do these parameters compare to the modern gold threads available from M.Maurer in Vienna and Golden Threads and Benton & Johnson in the UK? These three are the main gold thread suppliers in Europe. In a way, they are the descendants of the medieval thread makers. In the second part of the book, there is a whole chapter on design transfer. This is particularly important to us embroiderers. And whilst the chapter is not bad, one conclusion just left me speechless. On three of the vestments (Blue Kunigunde Mantle, Star Mantle and Reitermantle) remnants of the design drawing were analysed. As these remnants did not contain charcoal particles the use of the prick-and-pounce method was excluded. Huh?! Are you kidding me? Really?! All three vestments were made of dark-blue samite. The goldwork embroidery was executed directly on this dark silken fabric. Would any of you use black charcoal for the prick-and-pounce method? I surely hope not. You would use a white powder. And guess what? The remnants of the design drawing of two of the three vestments did contain white substances. The other one used a yellow one. And these substances were (also) used to make a kind of a paint. When you paint over the dots with a similar coloured paint-like substance these two likely mix. When you only have remnants of the design drawing, how can you be so sure that they are not the result of two different steps? Instead, the author proposes that the design was being transferred using templates/stencils. However, they have a tendency to smudge and move when used on textiles with a paint-like substance. Now, let me be VERY clear. I am not saying that the prick-and-pounce method was used for the pattern design transfer on the Imperial Vestments. I cannot prove that. Neither does the absence of charcoal particles prove that the method was not used. As has been the case before with this project, the inclusion of a professional goldwork embroiderer would have helped. I've written about early glitches before: here. Throughout the book, the authors emphasize the high quality and professionalism of the medieval embroideries. These embroideries and their medieval makers would have deserved a professional goldwork embroiderer on the team! And no, that does not need to be me. I am not the only one :).

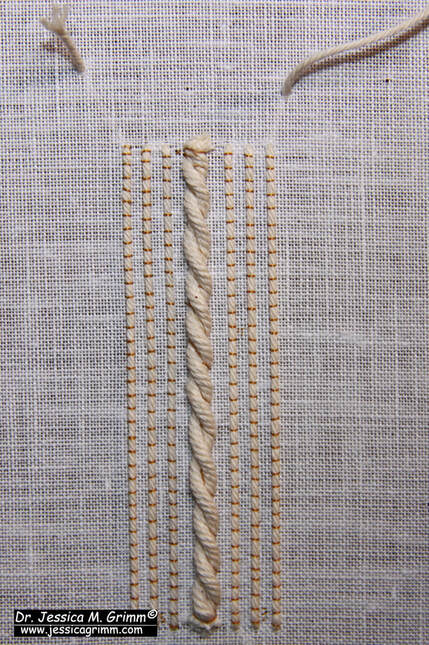

In the past two weeks, we have explored the early 15th century gold embroidery from Venice, Italy. One of its characteristics is the ornate orphrey borders with the twisted columns. I've always been curious how they were made! So out came the cotton padding threads and the gold threads and off I went. This kind of embroidery is best done on a slate frame. If you would like a reminder of what this is and how to set it up, please have a look at my instruction videos. Next, you will need to attach your string padding. The original uses two different kinds of padding. There seems to be something like soft cotton underneath the twisted columns. And a thinner string is used as padding on either side. I've used two thicknesses of the same cotton string for the padding. In order for the gold threads to be able to sit crisp on the padding, make sure that you couch down your padding well. The gold thread used in the original embroidery is a passing thread. In my recreation, I've opted for Stech 70/80, which is comparable to passing #3. I was also curious to know what the difference would be between a gilt and a real gold thread. I worked the main part of the sample with the cheaper gilt and the bottom section with the real gold (more yellow). I prefer the real gold :). It is a tat better at going and staying where I want it to go and stay. The result is a bit crisper. Still not as crisp as the original, but closer. If you have the opportunity to try different brands of passing thread, please do and see how they behave. Working over this amount of padding will cause slight problems. Although you place a couching stitch over the gold and in the 'groove' of the twisted column, the gold is not very securely attached in this place. The twisted padding threads are also very round. Your gold thread wants to 'escape' and roll off. This is also visible in the original embroidery. And it comes as no surprise that the embroidery is most damaged in this area.

My Journeyman and Master Patrons will find a downloadable PDF with this stitch sample on my Patreon page. As I am travelling in the coming week, there will be no blog post next Monday. I will be visiting various Diocesan Museums in Germany and the Netherlands. All my Patrons will be able to virtually travel with me as I hope to be able to post some pictures along the way. There will also be a meeting of the Medieval Embroidery Study Group for my Master Patrons on Saturday the 2nd of December at 19h CET. Details can be found on my Patreon page. From last week's blog post, you might have gotten the idea that Venetian goldwork embroideries from the early 15th century are somewhat plentiful. They are not. However, another magnificent piece was exhibited at Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento, Northern Italy. Some parts are remarkably modern in their appearance. Parts of the design could be easily adapted for modern goldwork embroidery. Let's have a look at the medieval eye candy. The embroidered chasuble cross on the red chasuble comes originally from the Church of San Pantalon in Venice. It is now kept in the Frari church in Venice. From the top, we see the Resurrection of Christ, Gregory the Great, Saint Jerome and Saint Augustine with angels in the side arms of the cross. There is another corresponding chasuble cross on the front. Unfortunately, the way it was exhibited did not permit the viewer to see the front as well. On that chasuble cross are depicted Saint Mark (tentative identification), Saint Ambrose and Saint Catherine with John the Baptist and a male saint on the side arms of the cross. Personally, I love this type of iconography. We have the four fathers of the church: Gregory the Great, Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo and Jerome. All four are seen as important theologians of the late Roman-Early medieval church (that's roughly 800-1000 years before this embroidery was made). Then there are Saint Catherine and John the Baptist. Two very important saints seen throughout the Middle Ages all over Europe. The story of Saint Catherine is also all about learning, philosophy and theology. A chasuble with a high IQ. As you can see from the orphrey of Jerome in the picture above, the embroidery is a bit damaged. The orphrey has warped quite a bit and this made it difficult to take good pictures. The shaded inky underdrawing is very fine and of exceptional quality. And so is the embroidery (made with gilded silver foil around a yellow silk core or silver foil around a white silk core). The goldwork is very accurate and the silken directional split stitches are very small and regular. As seen on last week's embroidery, the frame around the orphrey is padded. And we see the twisted padded columns again. And did you spot the 'measles'? This time, they are not located on the clothing (except for the hat of Jerome, see above). Instead, they decorate the multi-coloured arches (not really or nue as there is no shading; there is on the armour of the soldiers in the Resurrection scene) beneath the pinnacles and the large blue dome. In this case, the 'measles' are made over a disc of pressed paper. The same padding material is also used in the thicker parts of the pinnacles. Paper was a rather 'modern' material. Its use in Italian embroidery shows that trading ports such as Venice had easier access to it. It is not seen as a padding material in embroideries from Northern Europe. I absolutely love this background! It looks so very modern and oriental. This would make for a lovely modern embroidery design.

If you would like to see more downloadable pictures of this amazing embroidery and if you would like to join our Zoom call on the early 15th century embroideries from Venice, then please consider becoming a Patron. Your monthly contribution keeps this blog and my research going. Thank you very much! Literature Prá, Laura Dal; Carmignani, Marina; Peri, Paolo (Eds.) (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Trento: Castello del Buonconsiglio. In September 2019, I visited the exquisite exhibition "Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta" in the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento, Northern Italy. Together with the 2015 exhibition in the Catharijneconvent and the 2016 Opus Anglicanum exhibition in the V&A, this was one of those 'must-see' exhibitions. This one visit provided me with research material for several years. Especially as I was allowed to take as many pictures as I liked. As long as you don't use flash, the textiles absolutely do not mind. Today, we are going to look at some early Venetian embroidery. It includes some techniques unique to the Venetian embroidery workshops. Let's dive in! As you can see in the picture above, the cope is no longer an actual vestment. Only the mutilated orphreys have survived. They were used secondarily on an antependium which was probably made at the end of the 19th century. The orphreys were taken of this newer antependium in 2006 when they were restored and applied to a neutral backing. The orphreys represent three pairs of saints facing each other, a smaller square orphrey that would have sat on the neck of the wearer and which connected the two sets of three and part of the cope's hood with the Coronation of the Virgin. Identifiable among the saints are: John the Baptist (top left), James the Great (top right), Bartholomew or Peter (middle left) and Saint Jerome (square in the middle). The embroideries were made in a Venetian embroidery workshop around AD 1410-1417. When you look at the outer garments of the figures, it looks like they have the measles. These 'measles' are actually characteristic of Venetian embroidery. The 'measles' are made by covering a metal disc, with a central or off-centre hole (think spangle/sequin), with gold thread. Some discs are made of pressed paper. The gold threads that cover the discs are worked in gimped couching, but with an underside couching stitch. Proof again that underside couching is not exclusively English. Keeping the gold threads from rolling off the edges of the padding was probably no small feat! Another characteristic of Venetian embroidery is the elaborate dimensional frame around the orphreys. String padding is used to achieve the different textures. By using strings with different thicknesses, they could achieve several 'levels' in the frame.

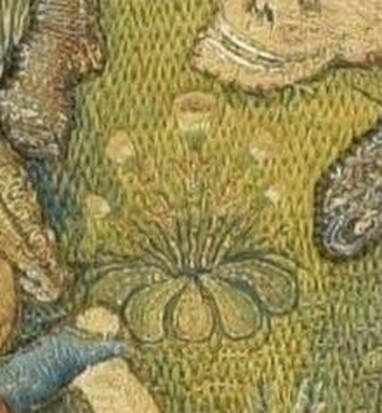

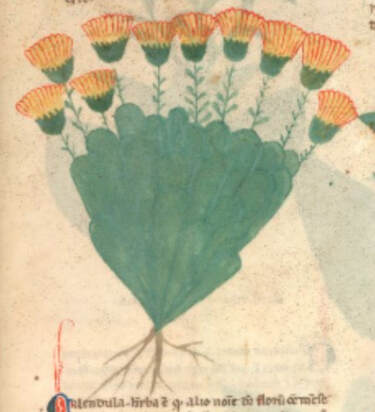

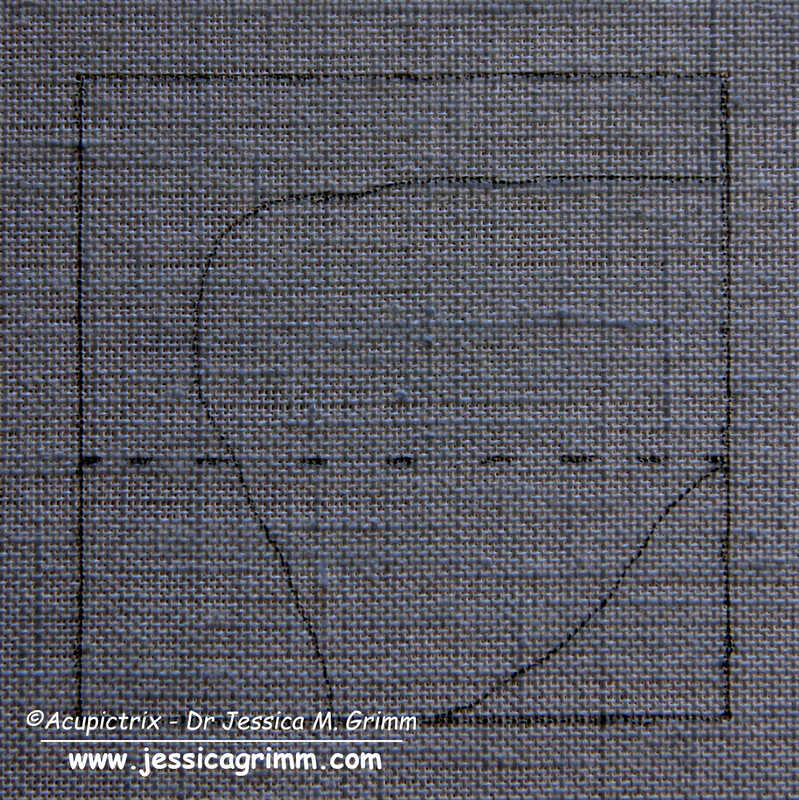

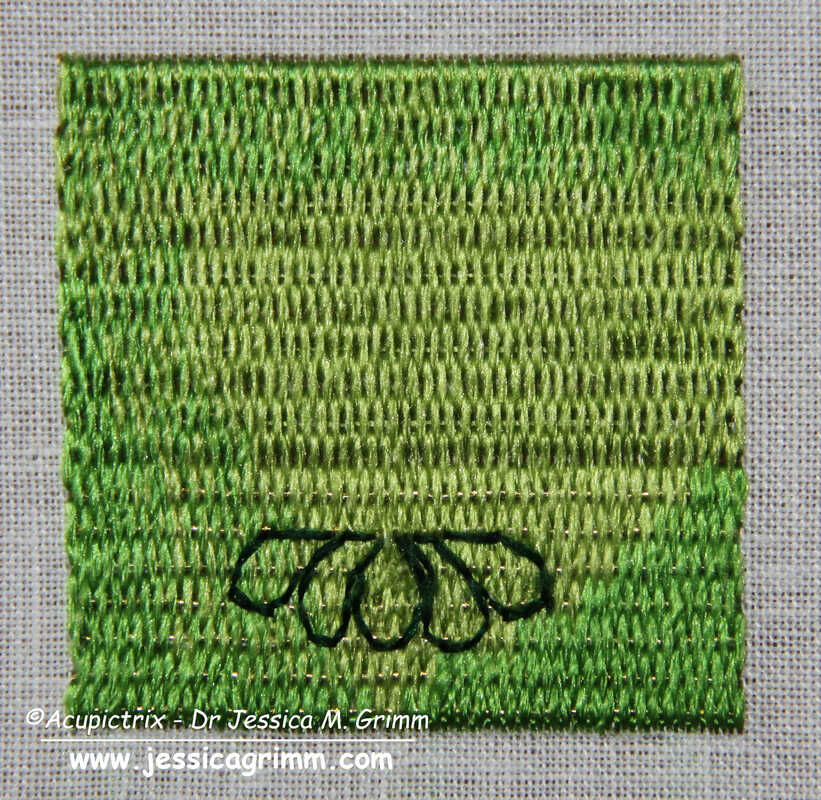

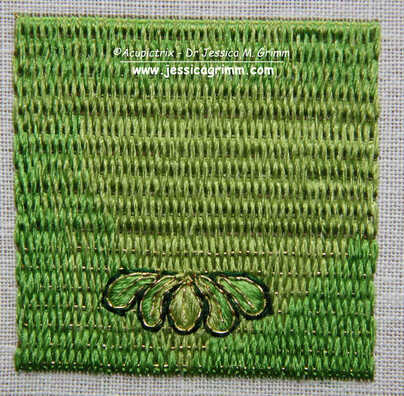

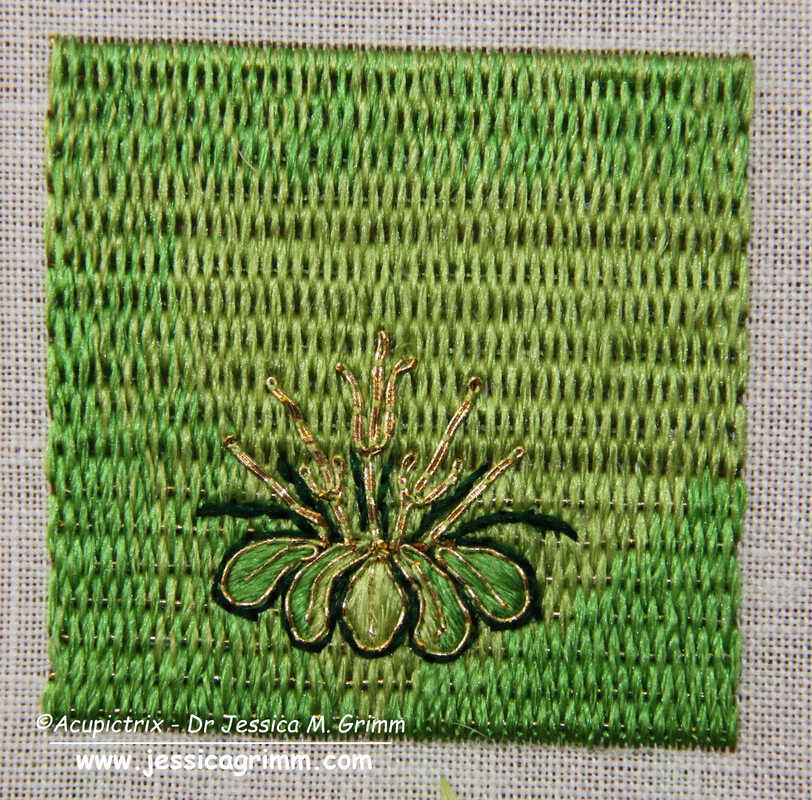

In general, many different embroidery techniques are used in these Italian embroideries from the Middle Ages. There is beautiful (directional) split stitch in silk, there is laid work, diaper couching and trellises. Or nue is absent as that was probably invented in the Southern Netherlands/Northern France and had not yet made its way to Italy. If you would like to see more (detailed) pictures of these nine orphreys, then please visit my Patreon page. Journeyman and Master members will find 23 images which can be downloaded. Literature Prá, Laura Dal; Carmignani, Marina; Peri, Paolo (Eds.) (2019): Fili d'oro e dipinti di seta. Velluti e ricami tra Gotico e Rinascimento. Trento: Castello del Buonconsiglio. We have been exploring the embroidery and the iconography on the lone cope hood from the V&A (990-1888) in the past two weeks (part 1 & part 2). This week, I'll show you how to work a small embroidery sample based on one of the flowers seen on that cope hood. It is an exercise in both counted threadwork and free-hand embroidery. It also teaches you to work goldwork embroidery on top of a base layer of goldwork embroidery. This was common practice in late-medieval goldwork embroidery. It is often done to hide the ends/turns of gold threads and it adds some depth. Below is a summary of how the sample was probably originally stitched. Journeyman and Master Patrons can download a 9-page PDF with detailed instructions. My clever husband happened to have a book on medieval flowers and was able to identify one of the flowers on the original cope hood as marigolds. The Egerton Manuscript from c. AD 1300 (MS 747, f. 30r) shows a drawing of the marigold that is quite comparable to the embroidered version. The embroidered version is about 3,5 cm high, and the detail is amazing. As you can see in the original, the marigolds are stitched on top of a layer of Brick Stitches (upper part) and Burden Stitch (lower part). These are both counted thread techniques. The foundation thread for the Burden Stitch (a passing thread) also runs under the Brick stitches. It is just being ignored. It is needed under the Brick stitches as padding. If you omit it, this section will be flatter compared to the Burden stitches. As the gold thread is (nearly) completely covered by the Brick stitches it shows that the price of gold thread had come down considerably by the end of the medieval period. Start your sample by drawing a 5 x 5 cm square on the grain of the fabric. You can also add guidelines for the shading and for when you want to change from Brick to Burden stitch. I am using a 46 ct linen, Stech vergoldet 80/90 (comparable to passing thread #4) and Chinese flat silk from Oriental Cultures. Start by laying the passing thread foundation. My passing threads are spaced 5 fabric threads apart. Once your base layer of Brick and Burden stitches is in, the fun free-hand part begins! And this is where each sample will become truly unique. Start with outlining the five green leaves. I've used a simple back stitch, but you can also use stem stitch. These are then filled with a few satin/straight stitches. On top comes an outline and vein (stitched in one go) in couched gold thread. Next up are the stems. They are made of gold thread. Start at the top (where the flower attaches) and separate the two threads to form a leaf on either side of the stem. Re-unite the threads again to form the bottom of the stem. Add dark green stems for a bit more definition. I've used stem stitches. The flower heads are stitched in long-and-short stitches (i.e. split your stitches). Start with the green bits at the bottom. Then add the light-yellow bottoms of the petals and end with the dark yellow tops. The central flower gets a flower heart made of a couched piece of gold thread. And that's your marigolds finished! Mine turned out more like dandelions ...

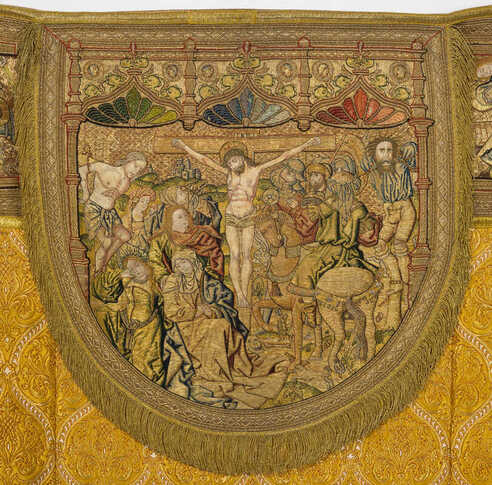

One of the things that amazed me when I was whipping up this embroidery sample, is the fineness of the original embroidery. My rendition looks bulky in comparison. Another hint that the original cope hood was once part of a very high-end vestment intended for an important clergyman and/or church! Literature Fisher, C., 2007. The Medieval Flower Book. The British Library, London. Last week, we explored the iconography and the embroidery techniques used on a cope hood from the V&A. The museum acquired the cope hood in 1888 and nothing more is known about it. Ever since I saw the piece in November 2019, I have wanted to know more about this outstanding piece of embroidery. And I have found some intriguing parallels in my ever-growing database of medieval goldwork embroidery. By now, my database contains 40 cope hoods that date to the 15th and 16th centuries and that are made in the historic Netherlands (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands). Of these, only 22 also have their matching orphreys preserved. Not a huge amount of data to work with ... My closest match is a cope hood from a cope from Averbode Abbey in Belgium. The scene is very similar to the crucifixion scene on the lone cope hood from the V&A. And the embroidery techniques are similar too. There's a lot of high-quality or nue in the figures. And the grassland is partly stitched in Burden stitch with additional plant motives on top (some grassland is or nue). Thanks to the accounts of Averbode Abbey, this cope can be precisely dated to AD 1530. The lone cope hood from the V&A dates to the second half of the 15th century (1450-1499). This would mean that there is a time difference of 30-80 years between the two. As this cope is still complete, we also have an idea of what the matching cope orphreys of the lone cope hood of the V&A might have looked like. There are six orphreys in total and they show: Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, Betrayal of Christ, Christ before Pontius Pilate, Flagellation of Christ, Crowning with thorns and Christ carrying the cross. Do click on the link above to see more pictures of the cope. You can enlarge them and/or download them. One of the things that makes the design of the lone cope hood from the V&A so outstanding is the amount of storytelling that's going on. Embroidered art can be pretty static. The above cope hood from Museum Catharijneconvent also has a very dynamic design with whimsical details. See the man untying his shoes? And the woman being helped out of her coat? These people are preparing for their own baptism. Some people look on in quiet contemplation whilst others look a bit sceptical. It needs a good designer, in this case, Jacob Corneliz van Oostsanen, and an equally brilliant embroiderer to put it into stitch!

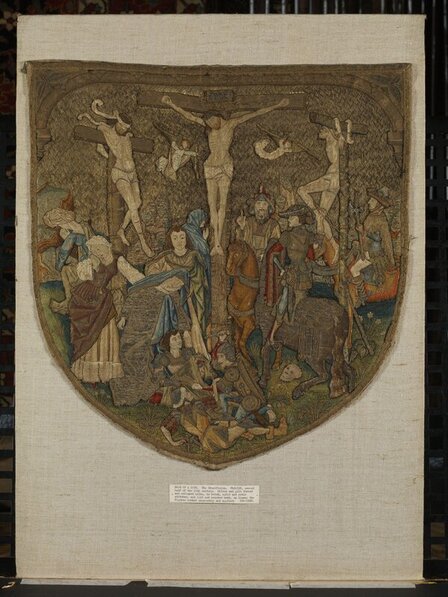

This cope hood was made around AD 1520-1529 in Amsterdam. That's about 30-70 years after the supposed stitching date of the lone cope hood from the V&A. Maybe the lone cope hood from the V&A should be dated a little later? Any art historians in the audience that could chime in on this? When everything goes to plan (hear the universe roar with laughter?), we will try our hands at a little bit of recreation of a small part of the lone cope hood next week! Literature: Gerits, T. J. (1973): Historische schoonheid van Averbode. Averbode: Abdij der Norbertijnen. In November 2019, I visited the Clothworkers' Centre in London to study several pieces of embroidery kept in the V&A collection. One of these pieces was a cope hood from Flanders made in the second half of the 15th century (Accession Nr. 990-1888). The piece was bought in 1888 by the museum and lacks any further provenance. Lone cope hoods are pretty common in museum collections. This part of a cope is already relatively loose and could easily be separated before being sold on the art market. Pieces without provenance, like this lone cope hood, always make me a bit sad. So much information was lost. Nevertheless, it is a very fine piece of late-medieval goldwork embroidery. Let's explore! The cope hood measures 53.3 x 51.4 cm and the embroidery fabric is a finely woven linen. Originally, the hood would have been trimmed with some sort of decorative fringe. It likely also had a tassel of some sort dangling from its lowest point. In those areas where the embroidery has fallen out (lower part of the undergarment of the lady with the red dress on the left), a finely shaded underdrawing is visible. Although I am generally not very keen on crucifixion scenes, this one I quite 'like'. There is so much going on. There is so much movement. And there are so many fine details. This is late-medieval art at its best! The design is very high quality and was likely made by a famous artist. Maybe a painter or someone who designed church windows (we know from written sources that they provided embroiderers with designs too). It is highly unlikely that the design stems from an embroiderer who happened to be a fine draftsman too. So, what do we see? And how was it embroidered? We, the viewers, are looking towards Golgotha from under an arch (probably the city gate of Jerusalem as Golgotha was 'outside the city gate' according to Hebrews 13:12). The arch is a far more intricate piece of embroidery than what it looks at first glance. It is partly embroidered as a continuation of the diaper pattern background (capitals on the sides), whilst the gold threads of the rounded arch neatly cover the turns of that same diaper pattern. The silver trefoils in the corners are also very intricately embroidered. There's twist and something that looks like a chain stitch executed with passing thread. On the arch itself, halved quatrefoils are embroidered at regular intervals. Their 'petals' are actually part of the arch. By couching 'petal' outlines onto the arch, the quatrefoils emerge. The diaper pattern used for the background is of the common open basketweave type. The couching stitches were once bright red; the most common colour used. Also part of the background are beautifully stitched rocks. They are embroidered directly onto the background linen. The rocks are made with Burden stitch and use a variety of green and brown silks. On top of this base layer, additional details are stitched with silks and gold thread. The rest of the background consists of a meadow stitched with several shades of green in Burden stitch. At the top, the Burden stitch is worked very densely so that the foundation gold thread can hardly be seen. Towards the bottom, we see the gold thread clearly. On top of the grassy base layer, grasses and several species of plants are stitched with silk and gold. None of the plant shapes is repeated. The flowering plants have different flowers. Maybe the plant lovers in my audience can identify them? Also present in the meadow is a rather funny-looking skull. It has lost most of its embroidery but is still readily identifiable. The skull is a hint to show that we are at Golgotha. According to the bible, Golgotha means 'place of the skull'. And what's with all the people on this piece? They actually tell different parts of the gospels in one very lively scene. Firstly, there are the three crucified people: Jesus in the middle flanked by two criminals. See the body language of those two criminals? The one on the left looks submissive. The one on the right not so much. He even sticks out his tongue. The story of the good thief and the unrepentant thief is told in the gospel of Luke. Interestingly, the crosses of Jesus and the good thief are identical (made of timber), whereas the cross of the unrepentant thief is made of green wood. Has anyone seen this before in embroidery or a painting? Oh, and then there are the two angels with their chalices catching Jesus' blood for the Eucharist.

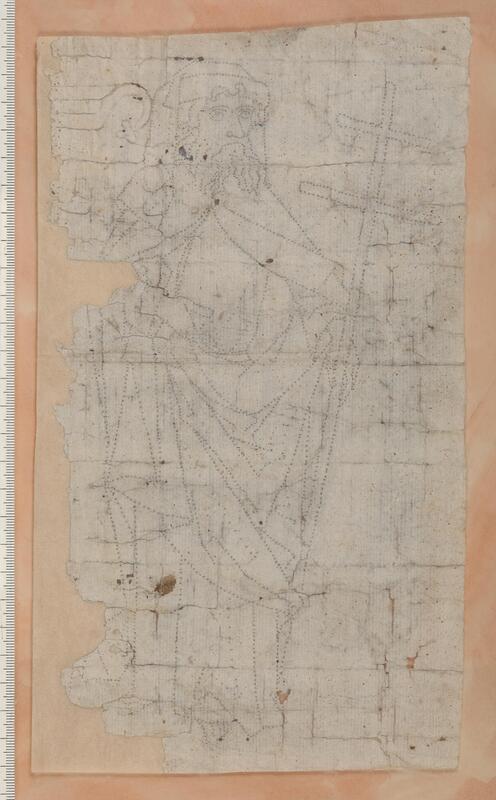

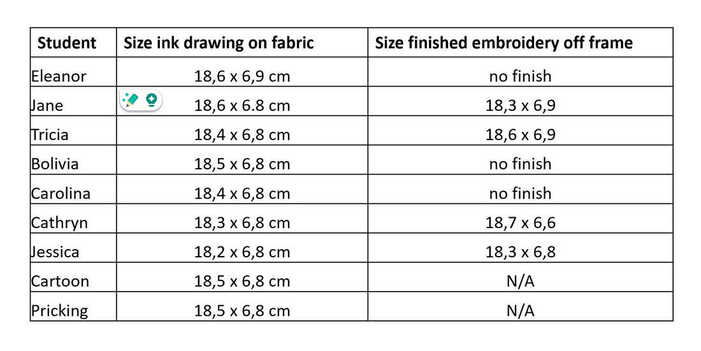

Next up, are the people on the left. They are on the good side with the good thief. We see four women and a man. The woman on the left with a fancy laced red dress is Mary Magdalene. The woman to her right is Mary mother of Jesus. She is fainting and being caught by Saint John who stands behind her. The two other women in the back are sometimes known as Salome and Mary the wife of Clopas. The bible is vague about these other women. Is this why the designer decided to show them only from the back? On the 'wrong' side are three horsemen. Two are clearly soldiers as they wear weapons. But who is the guy with the strange hat? He points up. What does he want? Is he pointing at Jesus? Is he the centurion who according to the gospel of Mark identifies Jesus as the son of God? Or is he a Jewish priest (as the V&A website suggests)? Any ideas? The last group of figures sits at the bottom of the cross. Three soldiers are dividing Jesus' garment to each have a piece. This is also a well-known story from the gospels. Whoever drew the design for this cope hood was very well acquainted with the biblical stories. Far more so than most people are today. How are all these different figures stitched? None of them are stitched directly onto the background linen. Instead, single figures or a group of figures are stitched on a separate piece of linen and then appliqued onto the background. This creates a little bit of depth in the embroidery. Can you see some of the crude white tacking stitches along the edges of parts of some of these figures? These are later repairs. It never ceases to amaze me that people repaired these very high-class embroideries with such crude stitching in later times! Have a good look at the embroidery of the figures. You will see beautiful or nue in the clothing of some of the figures, on the crosses and on the horse. There is also beautifully shaded medieval long and short stitch (it is more a counted thread technique than our modern version of long and short). The use of both gold and silver thread further enhances the design. The quality of the embroidery matches the quality of the design. This would once have been a very expensive piece of embroidery. It was probably commissioned by an important church or important church leader. Think cathedral or bishop. If we only knew for which church it was originally intended. Or who designed or stitched it! How much does the size of the finished embroidery differ from the cartoon and the pricking it was made with? Any idea? Me neither. But I read a reference by Evelin Wetter a couple of years ago that tried to link a rare surviving medieval pricking to a surviving embroidery. However, the measurements of both were slightly different. So how different are cartoons, prickings and the resulting embroideries? Time for an experiment and in comes Elisabeth. The original reference mentions the find of a pricking being reused as the backing for a finished embroidered antependium (to stiffen it) found in Hillersjö, Sweden. The pricking shows Philip the Apostle. The pricking is identical to an embroidered Philip the Apostle on a cope orphrey from Linköping Cathedral in Sweden. According to the reference, "compared to the pricking, the embroidery appears to have shrunk by a few millimeters". Unfortunately, I wasn't able to find precise measurements of either the pricking or the finished embroideries on the cope orphrey. From the ruler depicted in the picture of the pricking, the pricked figure must be about 24,75 cm. From the ruler in the picture with the orphrey of Philip the Apostle, the embroidered figure must be about 23.7 cm high (excluding the halo, just as in the pricking). If we compare this with the height of the pricked figure (24.75 cm) we have a difference of about 10.5 millimeters (slightly over a cm!). This would more or less correspond with the original reference's mention of 'a few millimeters'. It looks a little high to me, to be honest. And when my deducted measurements are correct, I doubt pricking and embroidery are identical. In the original reference, the difference between the size of the pricking and that of the embroidery is explained by the transfer process described by Cennini in his Libro dell'Arte of c. AD 1370. In it, a near-dry sponge is used to slightly wet the free-hand drawing to add shading. Now, there's several things mixed up here. Cennini described the embroidery design transfer process for a design drawn onto the embroidery process free-hand. The pricking of Philip the Apostle and the resulting embroidery stem from a very different process. No free-hand drawing. And as we can see in the damaged parts of the finished embroidery: it is a line drawing with no shading. The embroidery linen can thus not have shrunk, as the original reference of Evelin Wetter suggests, due to the application of a little water in the wetting process to add shading. If art historians make assumptions like the one by Evelin Wetter, you might think that they have conducted an experiment with modern embroiderers, don't you? But, nope. So, I decided to use my teaching at the Alpine Experience in 2022 as such an experiment. Just having my own measurements would be a bit skimpy on the data side of things. And I am very grateful that three students of that class finished their embroideries and that I was able to measure their embroideries during 2023's class. Here are the results: As you can see from the above table, the cartoon (design drawing) and the resulting pricking do not differ in their measurements. Everyone used the same pricking. The resulting design drawing on the embroidery fabric made with pounce and ink already differs slightly: up to 3 millimeters in height and 1 millimetre in width. Some are larger, others are smaller than the pricking. The finished embroidery differs up to 2 mm in height and 2 mm in width. Again, some are larger and some are smaller. This is the comparison we are after as this compares the pricking with the finished embroidery just as for Philip the Apostle.

My conclusion thus is that small differences in measurements between a pricking and the resulting embroidery are normal. These differences can go either way: larger or smaller. They are the result of the maker going through several transfer steps: pounce dots from the pricking, turned into an inked line drawing, turned into an embroidery. The absolute difference in millimetres thus directly relates to the size of the brush for the inking and the size of the embroidery materials. Particularly the width of the gold thread at the turns on the design line probably attributes the most to the size differences seen. A huge thank you to my students who were brave enough to tackle Elisabeth! You have provided me, and the wider research community, with tangible data on this particular topic. Literature Nisbeth, Åke; Estham, Inger (Eds.) (2001): Linköpings domkyrka. Inredning och inventarier. Linköping: Linköping Domkyrka. Wetter, Evelin (2012): Mittelalterliche Textilien III. Stickerei bis um 1500 und figürlich gewebte Borten. Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung. The 14th century Grandson Antependium. It is a pretty mix of embroidery techniques, styles, languages and geographical areas. Let's explore! The Grandson antependium is housed at the Historisches Museum in Bern, Switzerland and catalogued under Nr. 18. It is 244 cm wide and 88 cm high and consists of three separate parts. The knight kneeling to the left of the central figure of the Virgin and Child is the donor of the piece. His coat of arms identifies him as Othon de Grandson (c. 1238-1328). Although born near Lausanne in Switzerland, he became a close friend of King Edward I of England. Othon de Grandson travelled widely throughout Europe and the Mediterranean area when he joined the 9th Crusade. Othon accumulated great wealth and donated it to various religious institutions in both England and Switzerland. This particular antependium was donated to the Cathedral of Lausanne where Othon is entombed. With the amount of gold used for the embroidery, it must have been a very expensive piece. The central part of the antependium shows the enthroned Virgin and Child with two vases with foliage and two angels with censers on either side. The design has a Byzantine flavour which is emphasised by the Greek embroidered inscription for the name of Christ. But that's not the only language used. Mary is addressed in Latin and the two angels are addressed in ancient French. The design isn't purely Byzantine either: the censers are distinctively Western European. Byzantine embroideries with embroidered donor figures are not known in this era either. Where was this piece made? And for whom originally? Most scholars now agree that the central part of the embroidery was likely made in Cyprus. The island is conveniently placed en route to the Holy Land and also served as a retreat base when things went wrong during the crusade. Cyprus belonged to the Byzantine Empire with its Eastern Orthodox version of Christianity. At the same time, it had ample visitors from the West. Was the central composition mostly finished when Othon saw it at a Cypriot embroidery workshop? Where the texts added on his request? The knightly figure and the coats of arms certainly were. And then we have the two separate side panels. Very different from the central panel. Style, embroidery technique and materials used differ from the central panel. And their design is non-religious. The side panels are thought to have been embroidered in England as they sport underside couching. Is this a rare remnant of non-religious opus anglicanum? Did Othon come across two embroidered soft furnishings in England that together with the panel he probably acquired in Cyprus would make up a fitting antependium for the high altar in his cathedral back home? As the embroidery is cut at the top, the two panels were not specifically intended for that high altar when they were made. I think we see a rare glimpse of opus anglicanum 'for the noble home' preserved in this extraordinary antependium. What do you think? Literature

Martiniani-Reber, Marielle (2007): An exceptional piece of embroidery held in Switzerland: the Grandson Antependium. In Matteo Campagnolo, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (Eds.): From Aphrodite to Melusine: Reflections on the Archaeology and the History of Cyprus. Geneva: La pomme d'Or, pp. 85–89. Stammler, Jakob (1895): Der Paramentenschatz im historischen Museum zu Bern in Wort und Bild. Bern: Buchdruckerei K.J. Wyss. Schuette, Marie; Müller-Christensen, Sigrid (1963): Das Stickereiwerk. Tübingen: Wasmmuth. Woodfin, Warren T. (2021): Underside couching in the Byzantine world. In Cahiers Balkaniques 48, pp. 47–64. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed