|

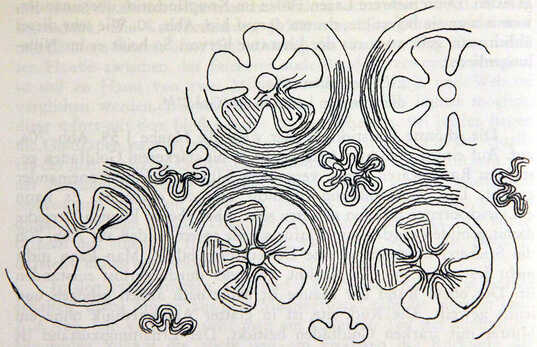

The majority of medieval goldwork embroidery is ecclesiastical showing corresponding iconography. A tiny proportion of surviving pieces can be associated with the nobility and might show non-religious designs. Absolutely unique are the finds of Villach-Judendorf in Austria near the Slovenian border. Archaeological excavations in 1968 revealed the graves of people who had been buried during the Hallstatt era till the high Middle Ages. Among the younger graves were at least four women who were buried wearing a bonnet with goldwork embroidery. The finds were extensively published in 1970 by Ingeborg Petrascheck-Heim. As far as I am aware, no newer publications exist. So out comes my lovely, always grinning, assistant Elisabeth to make sense of the black-and-white pictures in this important publication. How come so few examples for "normal" goldwork have survived from the Middle Ages? Gold can be recycled without quality loss. This means that worn clothes were deconstructed or simply burnt to retrieve the bullion. In addition, you needed a certain amount of disposable income as goldthreads, even the gilt ones, were quite expensive; the majority of the population did not have access to them. And even when people were buried in their goldwork-finery, only in exceptional circumstances did these textiles survive. Your best bet would be a sarcophagus in a cosy, slightly drafty, family vault. However, sarcophagi and family vaults are a rather expensive luxury reserved for higher-level clergymen and the nobility. Thank goodness for silver-gilt threads! Upon burial in the ground, the humidity and the larger silver component in the threads form salts that leak onto the surrounding area. In the case of goldwork embroidery, this is the textile component of said embroidery. The salts preserve this textile component. And although we will not end up with complete pieces of clothing as sometimes is the case in sarcophagi, the salt-caked fragments can still tell us a lot about the original goldwork embroidery. This is the case in Villach-Judendorf. Let's examine the four graves with the goldwork bonnets in some more detail. First up is grave J 57. Even with the help of my lovely assistant, I, as a former archaeozoologist, found it hard to correctly orientate the pictures in the article (see above). I think the suture on the left in the black-and-white picture is the one between the frontale and the parietale. The bonnet sits on the back of the head and the face (bones not preserved) would be towards the bottom of the picture. Amongst the textile remains you see in the above black-and-white picture is a black woollen bonnet with a design consisting of a nine-part trellis with spirals and trefoils. Unfortunately, the poor preservation of the bonnet does not allow for a more accurate pattern reconstruction. The goldwork embroidery consists of normal couching of two parallel threads with a silken couching thread. The goldthread (width 0.25 mm) consists of a 0.3 mm wide silver-gilt strip spun (S-direction) around a silken core. Grave J 59 contained a bonnet made of silk on which a repeat pattern of simple five-petal flowers in a circular frame (c. 3.6 cm high) was stitched. The areas between the circles are also filled with a kind of abstract wavy thingy :). Again, the goldthreads are couched down in pairs with 35-40 threads per centimetre. Two different goldthreads are used in this design: 0.25 mm width (0.25 mm wide silver-gilt strip around silk core) and 0.4 mm width (0.4 mm wide silver-gilt strip around red silken core). There is also a strip of bead embroidery on this bonnet. The beads are 2-3 mm in diameter and are made of gilt silver foil. The beading design could not be confidently reconstructed. Although the remains of the bonnet from Grave J 63 are poorly preserved, they do show that the goldwork embroidery is worked in underside couching. The publication does contain Ingeborg Petrascheck-Heim's reconstructed of the pattern. For the embroidery, two parallel threads are couched with a single stitch. The couching thread itself has not survived (probably thus linen) but the characteristic loops of goldthread at the back of the silk twill fabric unmistakably point to underside couching. The silver-gilt thread has a width of only 0.15 mm. The goldwork embroidery on the fragments of the bonnet in Grave J 105 is of very high quality. Unfortunately, the fabric has hardly survived but points to some sort of canvas. The embroidery design included roses in a circular frame, spirals, trefoils and acanthus leaves. Unfortunately, it cannot be confidently reconstructed. The goldthreads have a width of 0.15 mm and were couched down in pairs with silk. There are 45-50 threads per centimetre. The author assumes that, because of the higher quality of the embroidery, the bonnets in graves J 63 and J 105 (and probably J 57 too) were made by professionals. Bonnet 59 might have been worked by the wearer herself or someone else in her household. Where did these professional bonnets or the raw materials come from? Either complete bonnets were imported from beyond the Alps or raw materials were imported from beyond the Alps and fashioned into bonnets by local craftspeople. Certain characteristics of the (design of the) goldwork embroidery and the used fabrics point to a date around the middle or in the third quarter of the 13th century (AD 1250-1275). Although I concentrated on the goldwork embroidery, the complete headdresses of these women also included tablet-woven bands which include goldthreads and very fine veils made of silk. All this luxury points to a wealthy population that buried their dead in the burial ground of Villach-Judendorf. As the name "Judendorf" implies, some of these people might have been Jews.

If you are interested in non-ecclesiastical medieval goldwork embroidery, you should consider buying the publication from Ingeborg Petrascheck-Heim. It contains a full catalogue of all the gold bonnets (they have woven ones too) and 101 pictures and illustrations of the finds. You can order a copy by writing an email to Stadtmuseum Villach. The book costs only € 11 + shipping. Literature Petrascheck-Heim, I., 1970. Die Goldhauben und Textilien der hochmittelalterlichen Gräber von Villach-Judendorf, Neues aus Alt-Villach (= 7. Jahrbuch des Stadtmuseums), p. 56-190.

9 Comments

Monica

22/11/2021 19:36:17

Hi Jessica, very interesting and beautiful pieces! As to the suggestion that the wearers of these items of wealth may have been jews... the 13th century is one were antisemitism gets to a height (low) in western Europe. Such a display of wealth would certainly have been frowned upon, or worse.

Reply

22/11/2021 20:17:23

It is not of their wealth that these people might have been Jews. The name Judendorf means village of the Jews. The exact place of the burial ground is called Judenbichl, which means hillock of the Jews. Both names have been in use for centuries. Furthermore, jewish grave markers have been found and there is no church nor chapel in the vicinity.

Reply

Kathleen

22/11/2021 20:46:47

Considering the time period, location, culture and name, Villach-Judendorf was most certainly a Jewish cemetery. Aside from almost non-stop antisemitism in Eastern Europe for centuries continuing to today, Jews have always treated as a separate group within any community. And according to Jewish custom, members of the Jewish community are buried together in consecrated ground...except for the interruption of occasional pogroms! And so, I would imagine the bonnets do belong to Jewish women. In addition there may have been religious symbols worked into the design. It's hard to know isn't it?

Reply

Linda Hadden

22/11/2021 22:40:05

Another eye opening and amazing piece of information. Email sent for a copy of the book. Thank you for sharing x

Reply

Lyn

23/11/2021 02:56:31

Very interesting. On internet I've found out that Jews were expelled from places in the 13th and 14th century. So they established their own villages, such as Judendorf.

Reply

23/11/2021 09:03:30

Thank you Lyn! The information on the website you mention is mainly based on this short German paper: file:///C:/Users/DRB87C~1.JES/AppData/Local/Temp/26_MJ2010_Judendorf_1.pdf. However, although Judendorf is first mentioned in the 13th-century, it was likely established in the 10th-century as a small community of jewish traders. They moved into Villach proper by the 13th-century and even had a synagogue there. It is likely that they continued to bury their dead in the old cemetry outside of Villach in Judendorf.

Reply

23/11/2021 18:56:15

I think that re-examining these finds would already bring a wealth of new knowledge, Rachel.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed