|

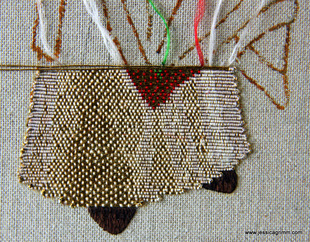

As several people have enquired after Laurence, I figured that I should make him the star of this week's blog post. Do you think a saint from the Roman period should get media training first before he makes an online appearance? After previously stitching his feet with Chinese flat silk, I've now made a start on his alb. An alb is worn by clergy under other garments such as the dalmatic or chasuble. As the Christian faith developed during the Roman Empire, many of its organisational structure and costumes are Roman. The alb, from the latin albus, meaning white, is a Roman tunica. Laurence's alb is stitched in or nue technique. Which means that, in this case, Japanese Thread #8 is covered by couching stitches of Chinese flat silk in two off-white tones. To give the impression of folds, the couching stitches are placed closer together or spaced out. It is not unlike silk shading or black work as taught at the Royal School or Needlework. As you can see, I have several needles on the go at the same time. Not bad for a first attempt. See the pink arrow in the picture above? There is a little bit of fabric showing between the alb en Laurence's left shoe. I'll mend that with a few extra stitches. And make a mental note to self that in the future I should go over the design line when working such areas. Oh, and just as modern gold embroiderers, our medieval counterparts didn't like plunging. So they just didn't. Really, they didn't! They just couched the thread till the desired design line and then snipped it off. As a good Royal School of Needlework girl, I was a little sceptical at that. However, no guts no glory. Below the pink arrow in the above picture, you see the tails of my old threads and the tails of my new threads. I ignored the fact that they are tails and just couched over them as my design required. I took the picture just before I snipped the tails off. Laurence has been brave too; after snipping he was still fine... And this is what Laurence looks like after 16 hours of stitching. I made a start on his green cloth of gold dalmatic with the red trim. Past and future blog posts on this project can be easily found by selecting 'St Laurence' in the category list to the right of this post.

7 Comments

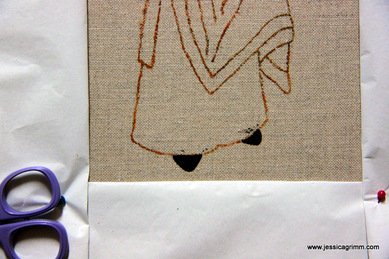

As a form of continued professional development, I'd like to complete at least one larger embroidery project a year. This year's CPD is going to be inspired by a medieval orphrey kept at the Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, the Netherlands. I wrote a blog entry on an exhibition of medieval goldwork embroidery from the Netherlands held at the museum last year. You can find a picture and details of the orphrey of St. Laurence patron saint of Rotterdam, and indeed many excellent pictures of embroidery, in their online catalogue. I contacted the museum for a high resolution digital picture of the piece. They were very helpful and within days I had the information I wanted. Firstly, I spend several hours on redrawing the image from the picture. Older textiles have a tendency to distort. After I was happy with the result, I made a pricking and pounced it. Painting with water colour on c. 40 ct. natural coloured linen wasn't easy. So far, I only had experience with nice smooth silk. My lines are a little thick and my paint didn't stay at the right fluidity for long. However, since the whole picture will be solidly packed with either gold threads or silk, it is not a problem. As you can see, the saint will be stitched separately from the background. He will be later appliqued to the background. I will also work some of the background ornaments separately. I intend to applique the whole piece on a scrap of red chasuble fabric. I've decided to start work on the saint. He will be stitched in Chinese flat silk and fine Japanese thread. Chinese flat silk has the advantage that I can split it to very fine strands of fibres. This will be especially important for my tapestry shading of the detailed face. As we attended Easter mass at 5:00h this morning, you will appreciate that I started with the least intricate part of Laurence: his shoes. They are worked in tapestry shading using two shades of a lovely dark chocolate. I split the flat silk in two. My tapestry shading is worked over a split stitch edge. That's all I managed today :).

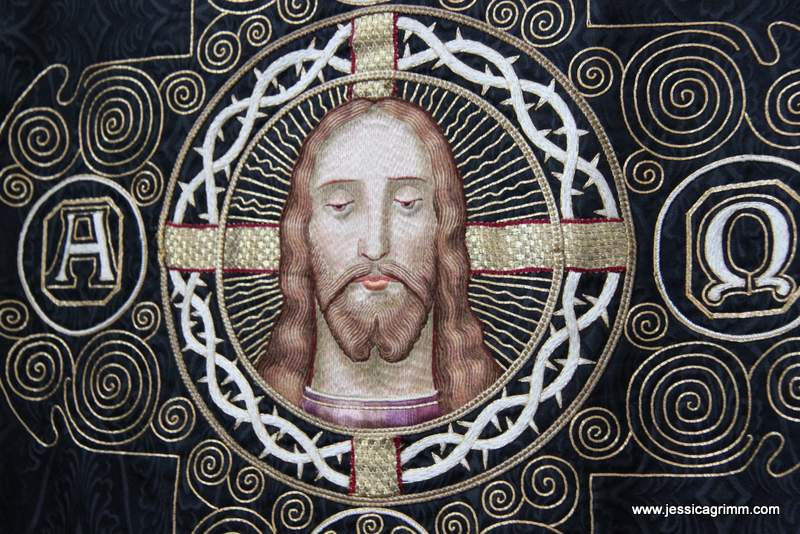

Tomorrow, two ladies from Switzerland and two from Germany will join me for a five-day course on Goldwork embroidery. I am looking forward to meet them and spent a week sharing my knowledge with them. More on their results in next week's blog. After that, I'll regularly keep you update on St Laurence. A few weeks ago, I visited a most spectacular exhibition at the Catherijneconvent, Utrecht, Netherlands. From their own collection and from the collections of other museums, convents and churches, they had brought together the largest exhibition on medieval paraments I have ever seen. Copes, chasubles and dalmatics were exhibited free standing on a dais so you could have a good look without being hindered by glass. Lighting levels were however still kept modest. Since only the best was good enough for God, medieval paraments were made of the most expensive fabrics finely embroidered with gold thread and silks. This meant that only the rich could afford to pay for them. One such a lucky bastard (literally: he was the illegitimate son of Philip the Good) was David of Burgundy, bishop of Utrecht from AD 1456-1496. Especially for the exhibition, the golden set of a cope, chasuble and two dalmatics donated by David to the St. Jan church of Utrecht was displayed together again. You couldn't tell that these pieces were more than five centuries old! And isn't this a delightful example of late mediaval embroidery? The silk embroidery on Christ's face and hair is so expertly done. Unfortunately, the level of lighting was particularly low in this part of the exhibition. This is a detail of a cope shield from AD 1520 depicting the resurrection. From a completely different quality is the above detail of a late 15th century chasuble. The angel is far less detailed and the gold threads are of a lesser quality. Hence they lost their lustre and became oxidized. After all, not everybody was a rich enough bastard like lucky David.

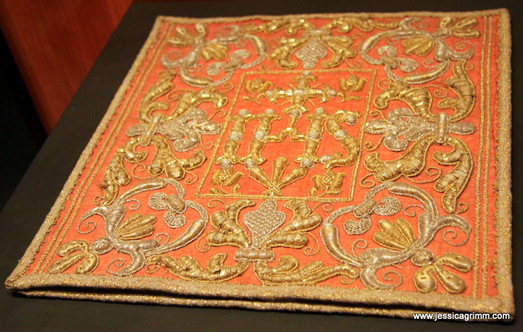

For those of you who missed the exhibition or simply lived too far away, the exhibition catalogue is a gem. More than 270 pages of embroidery goodness with many detailed photographs and a whole chapter on embroidery techniques by master embroideress Ulrike Mülners. Don't be put off by the fact that the book is in Dutch; the pictures will do the talking. Although I do agree that standard works shouldn't be written in such an obscure language like Dutch. Note: the book is now out of print but can be found second-hand online. In the coming months, I will show you more pictures of this exquisite exhibition. However, with the show at Osnabrück a mere four weeks away, I am up to my neck into writing tutorials, ordering materials and packing kits. See you next week after a short break in Vienna where my path hopefully crosses more gold threads... Literature Leeflang, M., Schooten, K. van (Eds.) (2015): Middeleeuwse Borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden. Zwolle: WBOOKS. Today we'll end our tour of the Regensburger Domschatz with three splendid paraments stitched in the 19th century. Generally speaking, I am not a huge fan of these 'newer' paraments as they tend to become too simple and almost hasty in their stitching techniques. This is especially true of paraments of the second half of the 20th century. However, the three pieces you are about to get acquainted with are still proof of high craftsmanship. The first piece is an antependium (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/88) or altar cloth entirely stitched with tiny seed beads! Do have a look at the enlargement of Luke's head and you'll see what I mean. The piece was stitched in Regensburg around 1890 and designed by Dean Georg Dengler (1839-1896). Dengler designed various pieces and saved many pieces of Christian art for future generations to admire. The largest piece in the collection is part of a throne baldachin (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/123). It was made in Southern Germany at the beginning of the 19th century. It contains, however, older parts. On red velvet, large floral motives in gold and silver threads are appliqued. The exotic flowers are filled with basket weaving patterns, whereas the stems and outlines are stitched with the guimped couching technique. The piece was donated by Archbishop Karl Theodor von Dalberg (1744-1817). A true child of his time, he was not only a church man, but also a Prince-Primate and a Grand Duke. The last sparkly piece I'll show you is a cope worked in goldwork and silk embroidery. It was made in Southern Germany in 1871/73 and donated by Bishop Ignatius von Senestrey (1818-1906). That's the end of our tour through the paraments of the Regensburger Domschatz. I hope you liked seeing these ancient splendours of embroidery craftsmanship. Next week I'll show you my embroidered version of Millie Marotta's fox. Fingers crossed I'll finish it on time...

I was never much of a Barbie's girl, however I do now wonder if Mattel ever made a bishop version. I would definitely buy one! And you might one too after you've seen the splendid gold and silk embroideries in this third post on the Regensburger Domschatz. When you enter the exhibition, you are greeted by this splendid mitra pretiosa (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/92), and precious she is indeed. Heavily encrusted with gold and silver embroidery, fresh water pearls and gem stones. The floral motives are worked in the guimped couching technique with a fine passing thread over card. Fillings are worked in various fine basket stitch patterns. Wheat ears are worked with looped purls and sequins are sewn down with fresh water pearls. The piece was made in 1793/94 AD in Regensburg. The mitre consists of two tapered shields (cornua) sewn together at the sides. The lining of the mitra is essentially still a cap. The two bands on the back are called vittae and symbolise the Old- and the New Testament. These episcopal gloves (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/93) date to the mid-18th century and were made in southern Germany. The extended cuffs (anicalia) are embroidered with delicate coloured silk and gold thread embroidery. Today, episcopal gloves are only seldom worn by bishops and other prelates. Of a completely different style is the cope (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/120) of the so called Stingelheim set. These liturgical vestments were donated by Dean Georg von Stingelheim (1741-1759). The vestments were made in 1740 AD in southern Germany. Colourful floral silk and gold embroidery on withe silk fabric. Look at the beautiful shading of the green leaves and the red central flower. One of my favourite pieces in the exhibition is this chasuble (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/112) covered in beautiful silk shaded flowers on a satin background. Texture is added by basket weave couching techniques in the cornucopias from which the flowers sprout. The shading is exquisite and the colours are still really strong and vivid. I can clearly see my little bishop doll wearing a miniature version of this!

I hope that these pieces have brightened your day too. And maybe they have even inspired you to a new embroidery piece. Do share your ideas below. Literature Hubel, A. (Ed.) (1976): Der Regensburger Domschatz. München: Schnell & Steiner. Today we will explore the post-medieval (16th and 17th century AD) paraments from the Regensburger Domschatz. The oldest piece, the hood of a cope, dates to the first half of the 16th century and was made in southern Germany. It is a very interesting piece as it consists of raised (stumpwork) embroidery. The scene depicts the last judgement. Unfortunately, this piece is really badly displayed: in a dark corner, where two sheets of glass meet. Why do museum conservators hate us interested embroiderers so much? This detailed picture shows many different stumpwork techniques. I particularly like the curliness of the figures' hair and the draping of their clothing. The background couching of the metal and silk threads is quite nice too. The piece made me chuckle when I started to study it more closely. Although the post-medieval period saw a revival of the practice of post-mortem examination, the results were clearly not widely available... Jesus' six-pack is of the same anatomical strangeness as seen on other contemporary art forms such as paintings and statues. Lucky for Jesus that things would soon make a turn for the better in the Renaissance period. The next piece I would like to show you is a chasuble (Inventar-Nr. D 1974/106) from the first half of the 17th century. It consists of a silk silver moire with bands of heavy gold and silk (yellow) embroidery. The gold embroidery consists of many small floral motives. It probably sparkled lovely in the candle light, but up close it looks a little too much and chaotic. On the lower back, the heraldic shield of the counts of Lodron, an Italian noble family is displayed. The last piece I am showing you today is a bursa from the second half of the 17th century. The bursa contains the corporale, a piece of fabric on which the Holy Communion is prepared. The red taffeta bursa is densely covered in metal thread embroidery. The alternating use of plate and twist threads over padding in some of the leaves is an interesting idea.

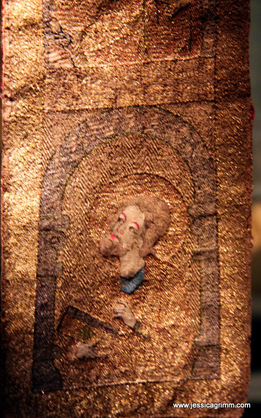

With this magnificent bursa I leave you this week. I am planning two future posts on the Regensburger Domschatz as there was sooooo much to see. Stay tuned if you would like to see a huge altar cloth entirely stitched in tiny seed beads. Last Thursday, I and my husband visited beautiful Regensburg, Upper Palatinate, Bavaria. As the skyline is dotted with spires, there's bound to be paraments. The Domschatz Museum sounded like a good hiding place. A small but very fine collection of exquisite paraments awaited us spanning the medieval to modern period. Although lighting was limited and sometimes really poor, I was able to take some good pictures. Too many to squeeze into one post. This post covers the medieval pieces and two future posts will deal with the post-medieval and modern paraments respectively. So do check back in the coming weeks if this is your cup of tea! The oldest piece on display is the so called Wolfgang Chasuble dating to the middle of the 11th century AD and made at Regensburg. Although this chasuble was never worn by St. Wolfgang of Regensburg (died 994 AD), the fact that it was attributed to him likely aided its survival. As you can see, only part of the original background fabric (a patterned blueish-purple silk) survives. However, the embroidery is in pretty good nick. Not bad for a piece of needlework that is nearly a 1000 years old! The embroidery depicts bands of alternating golden birds and quadrupeds biting into golden floral spirals. The background surrounding the animals and spirals is filled in with fine split stitches in silk thread. They used a bright blue, a grass green, white, grey and honey yellow. The split stitches surrounding the animals follow the circular flow of the spirals as well as the contours of the animal. The split stitches filling the areas between the spirals are worked more irregular. The animals are filled in by couching a single thread of very fine gold. Instead of the normal bricking pattern, horizontal lines are formed by the couching stitches. To enhance definition in the animals and spirals, a red silk thread is worked on the outlines. The embroidered bands are flanked by tablet woven bands depicting leopards and flowers. During my visit, I also came across a parament I had never seen before: a rationale from the first quarter of the 14th century made in Regensburg. It is given as a special papal distinction to bishops and was worn over the chasuble. This particular parament was inspired by the breast plates worn by the Jewish high priest. The use of the rationale mainly died out in the 13th century and today only a few bishops still wear one. This detail shows St. Jacob. His head and hands are stitched in fine split stitches with silk threads. The background consists of a myriad of geometric patterns using couching with fine gold threads of various sizes. The last piece dating to the late medieval period consists of a beautifully stitched crucifix re-used on a purple chasuble of later date. The embroidery dates to 1420 AD and was possibly made at Regensburg. It consists of gold embroidery and silk embroidery. Unfortunately, the light was so bad that detailed pictures were impossible to obtain.

The late medieval period marks a change in the liturgy and therefore in the shape and decoration of the chasuble. The Elevation of the Host before communion made it necessary to reduce the amount of fabric draped over the arms (compare the bell shape of the St. Wolfgang chasuble with the purple chasuble above). The priests also started to celebrate mass with their backs to the congregation. The back of his vestment became a large canvas for conveying the evangelion (again, compare both chasubles). The heavier embroidery called for lining. This in turn made the vestment much heavier and more solid, making it less suitable for raising the host as it trapped the arms. Born was the chasuble that leaves the arms largely free. More about that in my next post on the post-medieval paraments form the Regensburger Domschatz! Want to read more on German paraments? Karen Stolleis's book 'Messgewänder aus deutschen Kirchenschätzen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart' (2001, ISBN 9783795412548) is a real gem. Literature Hubel, A. (Ed.) (1976): Der Regensburger Domschatz. München: Schnell & Steiner. My guilty pleasure are richly decorated, sparkling chasubles (in the mists of time, one of my ancestors for sure must have been a crow). A couple of years ago, I was introduced to the chasubles designed by Leo Peters when they were on display in the Willibrordus church in Deurne, Netherlands. Peters worked in the style of the Art Nouveau with which he was successful around 1915-1920. His designs are very characteristic and easily recognisable once you have seen one. So here comes a bit of eye candy:

The National Museum has a handful of Late Medieval/Renaissance chasubles on display. By far and large, these are my favourite embroidered objects in any museum. You are in for a treat. The embroidery on the first chasuble (Inv. Nr. T278) was executed in Cologne in the third quarter of the 15th century (1450-1475 AD). The intricate diaper patterns were made using 'Häutchengold' or membrane gold also called Cypriot gold thread. It is comparable to Japanese gold, but was made by gluing gold leaf onto animal gut subsequently wrapped around a core of coloured silk or white linen. Here you can find an interesting article on medieval gold thread production by David Jacoby (2014). And here you can find an older article in German by Brigitte Dreyspring (2007). In the early 16th century, the embroidery was rearranged on the green velvet it is attached to today. Another chasuble (Inv. Nr. 65/163) with re-used late medieval (c. 1500 AD, Rhineland) embroidery. Click on the pictures to see a close up of the figures executed in fine silk embroidery and surrounded by diaper motives in membrane gold. However, the most elaborately stitched chasuble (Inv. Nr. T1499) is the one above. Do click on the pictures as the detail is stunning. The gold and silk embroidery was executed in Italy around 1500 AD. To achieve such a rich texture, the embroiderers used string padding and applique slips on both the silk figures and the oriental architecture. The style reminded me a bit of chasuble remains in the Catherijne Convent Museum, Utrecht (NL), showing the vita of St. Martin and St. Willibrord. However, those were made around the same time, but in the Netherlands.

I have been toying for a while with the idea of trying to replicate some of the highly textured architectural background of these pieces. If only I could find the time :). However, when I do, I will share the process with you. I have a few more goodies to show you from the National Museum, so stay tuned! Literature Durian-Ress, S. (1986): Meisterwerke mittelalterlicher Textilkunst aus dem Bayerischen Nationalmuseum. München: Schnell & Steiner. |

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed