|

Last year, I was lucky enough to visit the Abegg Stiftung in Riggisberg, Switzerland when attending the CIETA conference in Zurich. Their permanent textile exhibition is worth a visit anytime. We were also allowed to visit the conservation laboratory. That was a real treat! And I was able to browse their publications. In my opinion, they are the gold standard when it comes to textile publications. But that comes at a cost. And them being in Switzerland doesn't help either. So being able to see before you buy was a real bonus. One of the books I had been ogling for a while was: "Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund" (=Medieval liturgical vestments from St. Nikolai in Stralsund) by Juliane von Fircks published in 2008. Let's explore! The website description of the contents of the book does not mention embroidery. It turns out that the majority of the liturgical vestments from Stralsund do not have embroidery (some do, bear with me). Instead, they are made from different combinations of exotic silks. Many are woven with gold threads made of strips of leather. The designs are amazing and very exotic. They were made between 1300 and the second half of the 15th century. Their origins are Central Asia, Persia, Spain, Italy and Northern Germany. The silks made in Central Asia were known as panni tartarici (Tartar cloths) and were very popular in Western Europe. The vestments made with them look a little like a crazy quilt :). Very colourful and luxurious. Not only does the book describe these silks and their history and manufacture in great detail, the cut of the vestments is also extensively studied (with the help of Birgit Krenz). The silks were imported and then tailored locally (Northern Germany). As the Tartar cloths were so expensive, it is fascinating to read how the tailors made the best use of every little scrap. As said, the majority of the vestments from Stralsund are not embroidered. Of the 39 catalogue entries, only three chasubles, one bursa, one substratorium, one wreath and one possible hat brim are embroidered. All date between AD 1400 and AD 1500. One of the chasubles shows the familiar nativity story according to Saint Bridget. Another chasuble shows a floral/foliage design partly made of leather padding on which freshwater pearls were sown. Not a technique we see often. The third chasuble has a beautifully rendered Christ on the cross. The silken embroidery in fine split stitches is stunning. The substratorium shows lettering stitched in cross stitch. Unlike today, the cross stitch was rather rare in the Middle Ages.

But my favourite embroidery is the angel playing the lute on the back of the bursa. The embroidery of the angel and the clouds consists of linen slips appliqued onto red woollen twill. The thick white contour of the clouds indicates that these were once edged with freshwater pearls. Foliage and small white flowers are stitched directly onto the red woollen twill to form the background. The angel wears a tunic stitched in double rows of membrane gold (now dull and silvery in appearance). The rows run vertically and are couched in a simple bricking pattern. By cleverly starting and stopping threads and by adding a few darker lines for the folds, the definition of the different parts of the garment is achieved. As always, this book from the Abegg Stiftung does not disappoint. It has many beautiful pictures and close-ups of the different textiles. The chapters explain how the treasury of St Nicolai survived to the present day. And how difficult it is to identify surviving pieces from church inventories. Each catalogue entry has very elaborate technical details. What threads were used and on what fabric (mostly with thread count). At present, the museum in Stralsund is closed for refurbishment so I do not know if (some of) these pieces are part of the permanent exhibition. Before I became an embroideress, I visited the museum as an archaeologist and analysed some animal bone found in the refectory of the Katharinenkloster. That was some 20 years ago ... Literatur Fircks, J. von, 2008. Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund. Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg. Grimm, J.M., 2005. Keine Lust zum Geschirrspülen? Auswertung der spätmittelalterlichen Tierknochen und der botanischen Reste aus der Remternische des Katharinenklosters in Stralsund. In I. Ericsson & R. Atzbach eds. Depotfunde aus Gebäude in Zentraleuropa (=Bamberger Kolloquien zur Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit 1), Berlin, 173-180.

6 Comments

Although my library of books on medieval (goldwork) embroidery is filling more and more IVAR shelves, I still don't have everything :). Hunting publications down is a slow process. There's no central institution or website shouting new releases from the rooftop. Finding older publications often happens by reading through the footnotes and literature lists of publications already on my shelves. Especially chapters in books in which the subject is compared to other existing examples are really helpful. In the book on the Emperor's last clothes I showed you last week, I found some new-to-me information on the embroidery on the Imperial Regalia in Vienna, Austria. I've seen those. They are in a room very close to the spectacular or nué embroideries of the Order of the Golden Fleece. As the embroidered regalia are very old, they are not exactly in the limelight. The room is very dark. So the intriguing goldwork embroidery eludes probably most visitors. Let me introduce you to a very rare goldwork embroidery technique, I had never seen before. From the above picture I took, you can already tell that seeing details of the embroidery on the blue tunic is difficult due to the reduced lighting levels. The tunic was made in the first half of the 12th century in the Royal workshops of Palermo, Sicily. The red bottom seam contains embroidery in underside couching. This is seen in more pieces made in Palermo. The really intriguing embroidery is on the cuffs. From this poor picture I took, you can probably not instantly see what is so special about the goldwork embroidery technique used. If you look real closely, you might see that the embroidery is made of a kind of gold foil tubes sewn down like elongated beads and then flattened. The museum's website states that this is probably the only surviving piece in this technique. The caption in the museum does mention 'gold tubes' in the material list. But when you are not told where to look for them, it isn't easy to spot them in the dimly lit room.

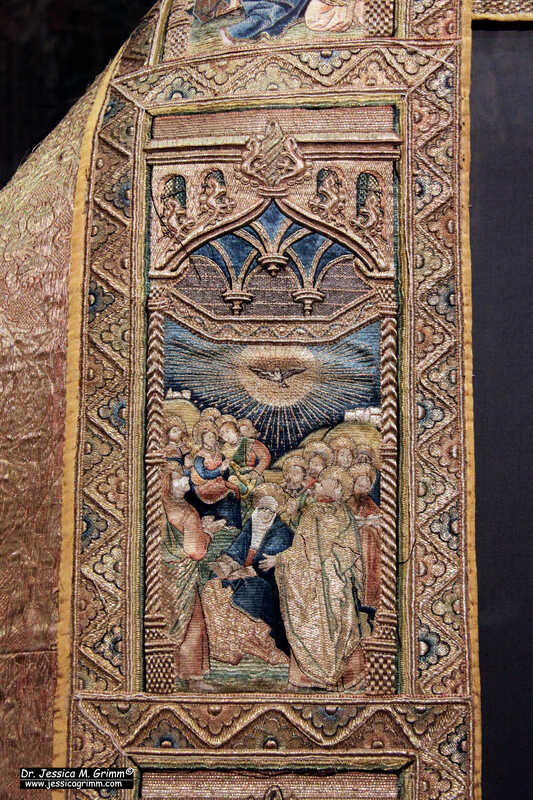

I am most intriguied by this embroidery technique as I feel that these golden tubes were quite fragile and easily deformed. Why did the embroiderer choose this technique and not (underside) couching also in use at the same time in the Imperial workshops? Is the effect achieved so different? Is it quicker to stitch? Or is it easier to make gold tubes compared to gold thread? Any ideas? A huge thank you to all who responded to last week's trestles and maschinenstock giveaway! All pieces have found good new homes and will be shipped as soon as the extra-large shipping boxes arrive. As with everything logistics nowadays this seems to take a bit longer than normal. Please be patient. And for now: let's visit some gorgeous medieval goldwork embroidery from Lausanne Cathedral and currently kept in the Bernisches Historisches Museum in Switzerland. When medieval embroidery is your thing, this is a museum you definitely want to visit. Apart from the vestments from Lausanne Cathedral and many others, the museum also has the Grandson antependium from the 13th-century on permanent display. The set of golden vestments from Lausanne Cathedral consists of a cope (inv. 307, now on display), a chasuble (inv. 39) and two dalmatics (inv. 38 & 40). The embroidery was made between 1513 and 1517, probably in Brussels, Belgium. This expensive set of vestments made with Italian fabrics and very high-quality orphreys from the Low Countries was commissioned by Bishop Aymon de Montfalcon of Lausanne. Aymon clearly had deep coffers! As Mary is prominently displayed on many of the orphreys it becomes clear that the vestments were always intended for Lausanne Cathedral which is dedicated to Our Lady. The design drawings on the linen underneath the embroidery were made with black and red ink. The correct shading is also indicated with the ink. There is not a full-colour drawing beneath these embroideries. It is more or less sparse monochrome-shaded drawing. Enough so the embroiderer was aided during his work, but not so strong that it obscured the weave of the linen fabric and made the actual embroidery harder. It is important for the embroiderer to still be able to see the weave of the fabric as the silk shading is more akin to Chinese silk shading (very orderly and counted) than it is to the type of silk shading taught at the Royal School of Needlework (which is random). Although all orphreys on all four vestments clearly belong together and were thus made around the same time in the same place, they do differ slightly in the execution of the embroidery techniques. I am sure you can separate out several different embroiderers when you study these orphreys in depth. The designs also differ quite a bit stylistically and were clearly inspired by several contemporary painters such as Gerard David, Bernard van Orley and Cornelis Engebrechtsz. Simple 'one saint' orphreys from the Low Countries often consist of two or more pieces sewn together: a separate saint appliqued onto an embroidered background (of which some very dimensional elements might also be slips). The more complex orphreys of the golden vestments are mostly worked as one piece with only some figures being worked as slips. This is probably easier (and thus quicker) when you have many partly overlapping figures in a single scene. The backs of the orphreys have been stiffened by gluing used paper onto them (letters, invoices, etc.). Interestingly, true or nue is absent from these orphreys. Instead, most figures are stitched in a form of silk shading. The main figures in the foreground may have parts of their clothing stitched with goldthread. However, the horizontally laid goldthreads are couched in a bricking pattern using gold-coloured silks. The folds are accentuated with some simple line stitches in coloured silks. I have coined the term 'pseudo or nue' for this specific embroidery technique. It is often seen on orphreys from Germany, but rare on orphreys from the Low Countries. True or nue can create fantastic shading and suggest three-dimensionality. Pseudo or nue cannot achieve this. The floral frames around the orphreys are also unique. So far, I have not come across a similar pattern with coloured flowers. This might have been a trademark of this specific embroidery workshop.

If you would like to learn more about the golden vestments from Lausanne Cathedral then please buy the museum publication "Himmel und Hölle in Gold und Seide" by Annemarie Stauffer. There is also a French version available. The book has detailed pictures and descriptions of the orphreys of all four vestments. The introductory chapter is also very well written. You can order the book (22 Swiss Francs) directly from the museum shop by sending them an email. Please remember: when you order from the museum directly you help them financially. Something museums can really use after the many closures during the pandemic! A couple of years ago, I saw the so-called Wolfgang's chasuble at the Diocesan Museum Regensburg (you can read my blog about my 2015 visit). It had this lovely embroidered cross with birds and a four-legged animal amidst scrolling foliage. Although the goldwork embroidery is quite damaged, it is clear that it was once a very high-quality piece of medieval goldwork and silk embroidery. Its design would make for a lovely (online) embroidery class. I've asked my husband to clean up one of the bird designs and this is what he came up with. The original embroidery was made shortly after AD 1050, probably in Regensburg. A royal residency at the time, Regensburg likely housed the royal workshops when the court was in residence. The way this embroidery, and indeed the whole garment, was made differs markedly from most contemporary pieces. Those pieces are usually all over embroidered and the embroidery is directly worked onto a precious silken fabric or a linen fabric. Good examples of these are the Imperial Vestments, the Uta chasuble and the vestments from Saint Blaise now held in St. Paul im Lavanttal. Many heyday Opus anglicanum vestments also fall into this category. Not so Wolfgang's chasuble. This one has a strip of separately worked embroidery adorning the precious silken vestment. This would become the way forward for the rest of the medieval period and beyond. It is essentially the birth of the orphrey. These smaller pieces of embroidery were far more manageable and could be prepared in advance. Goldwork embroidery could move out of the specially equipped royal workshops and into, probably smaller and simpler, commercial workshops in the emerging towns. But we can clearly tell that the process of 'how to make an orphrey' was not yet set in stone. In this case, the embroidery seems awfully complex when it comes to its backing fabrics. What had the embroiderer done? It started with a piece of natural coloured silk twill/samite on top of a fine linen. All goldwork embroidery (and probably the stem stitch outlines) was worked that way. Then the piece was backed again with an extra layer of linen before the fine silken split stitches were worked. Curious don't you think? I was told that you back your embroidery when the stitching is particularly heavy. That would be the goldwork and not the silk. Just imagine the sore fingers from pushing a fine needle with silk through three layers of fabric... But I have an idea why the extra layer of linen was added: stiffness. Later, orphreys were routinely backed by gluing recycled paper on the back or simply stiffening the back with a layer of glue. As I am trying to get hold of the right-ish kind of fabrics for this project, I cannot tell you yet when this design will become available. What I can tell you is that it will be a pre-recorded class that you can work at your own pace. You can start whenever you like, and you will have access to the class videos for at least a whole year from the date of purchase. The class fee will include a full kit. You will have various kit options to choose from. This mainly involves different qualities of gold threads. I will also likely teach this design as a weekend-long class at Glentleiten Open Air Museum next year. How does that sound? Do let me know in the comments, please!

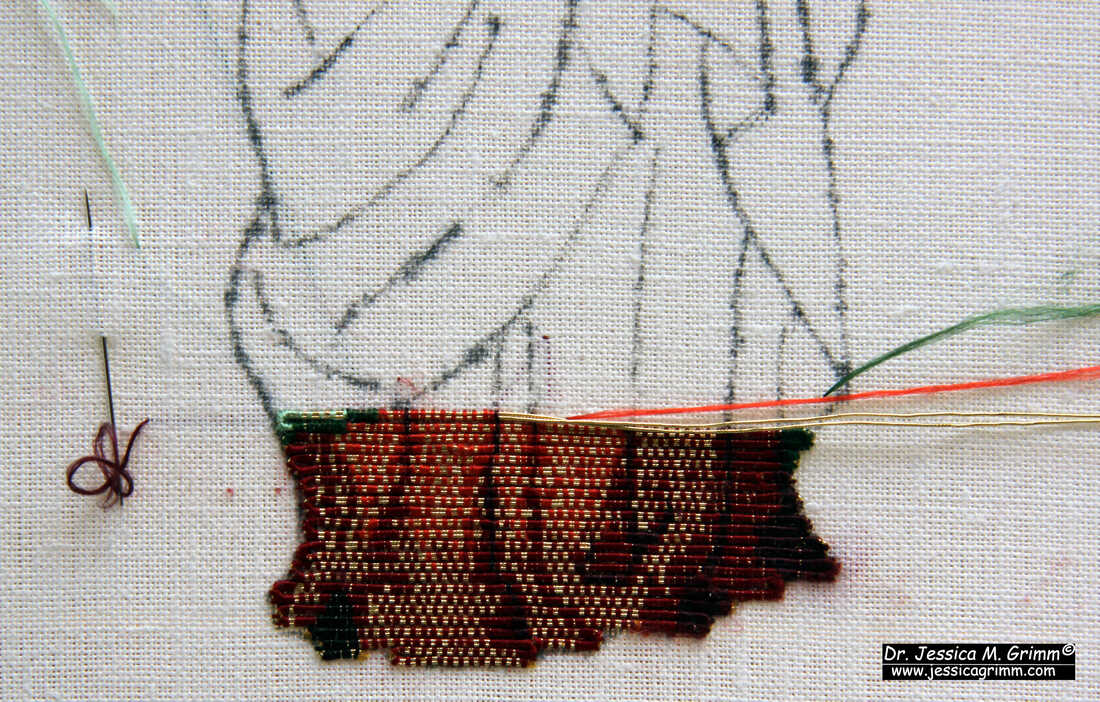

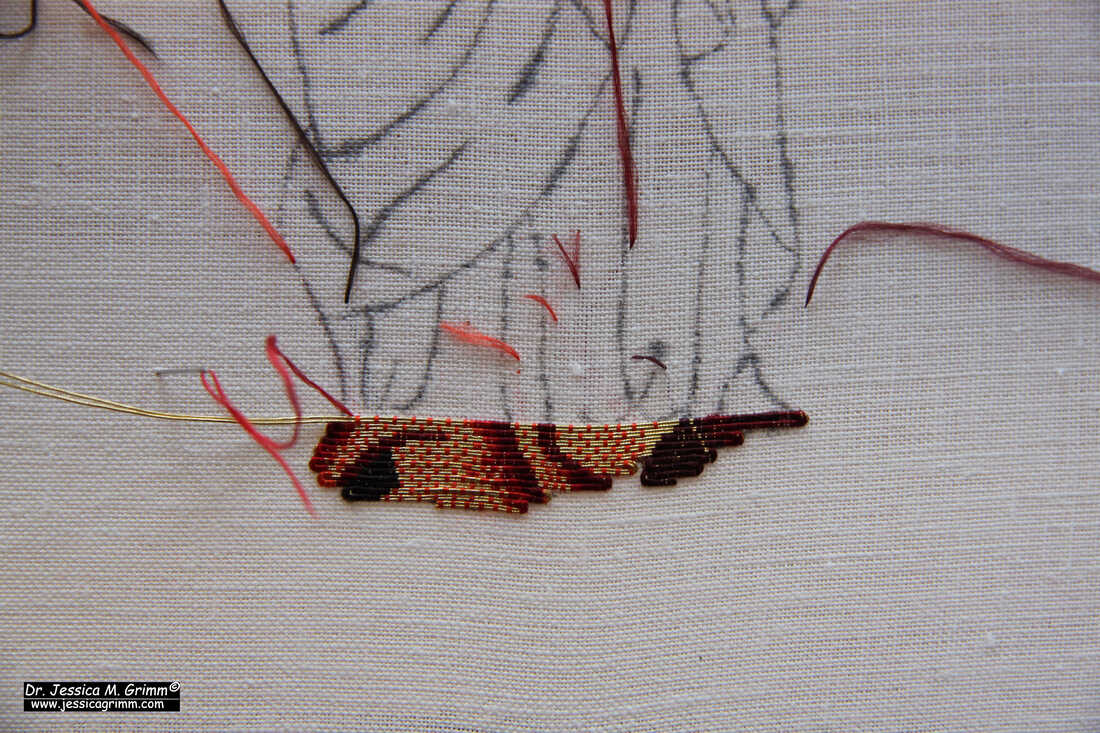

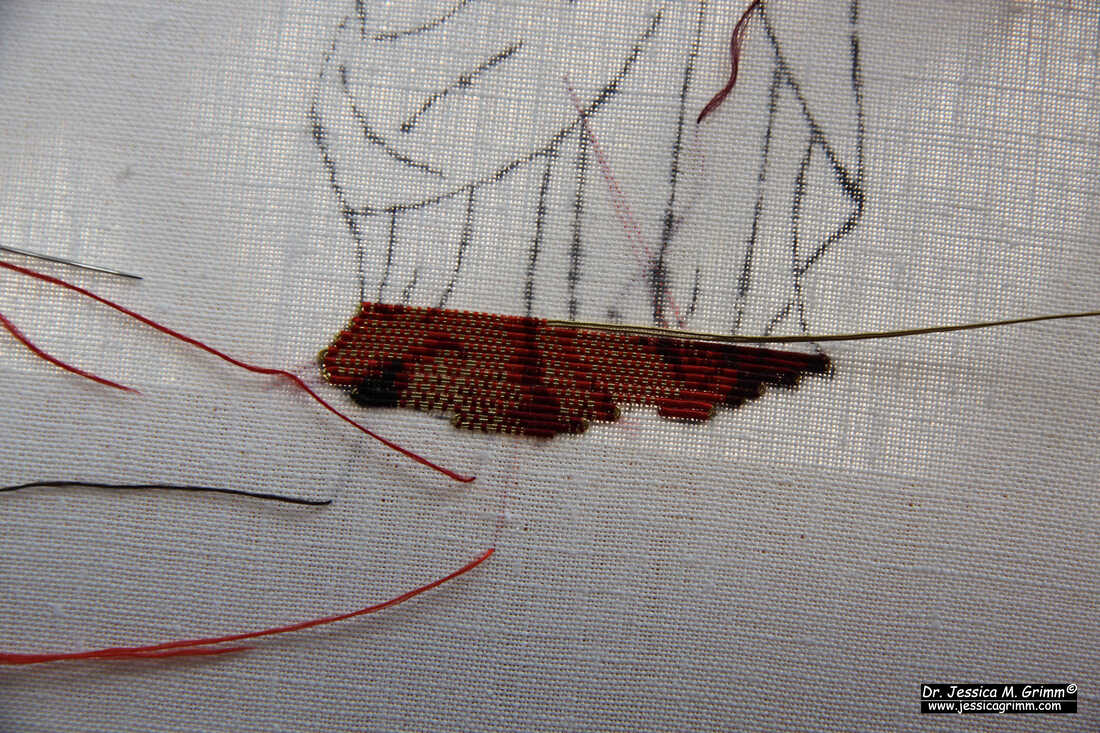

Last weekend, I taught a goldwork embroidery workshop at the Open-Air Museum Glentleiten near Munich. I set up class in the living room of building 61 (click here for some lovely pictures). This building was once a farmhouse built in 1566 (with parts of an older building dating to the late 15th century!) in the county of Altötting before it was transferred to the museum. The living room has lovely windows and is generally bright enough to embroider in when you sit near one of these windows. However, I made sure each student had a magnifier lamp too. My idea is to do at least one of these workshops in Glentleiten each year. So let me show you what such a workshop looks like. Maybe I'll whet your appetite :). For my courses and workshops, I'll take a maximum of 10 students. This assures that you'll get plenty of my attention. As the museum has many spaces to choose from, the number of students determines which building I will set up the classroom in. Classes run from 10 in the morning till 4 in the afternoon. As the museum does not close until 6, you'll have plenty of time to explore the other buildings in the beautifully manicured museum park. Each day, we'll break for lunch at about 12:30 and resume stitching at 13:30. The museum has two lovely cafes where you can get a cooked lunch, sandwiches, soups, cakes and some old-fashioned local foods. You either eat in a historical dining room or in the beer garden. However, it is perfectly fine to bring a packed lunch and find yourself a nice spot to eat. And this is the 'workstation' each students gets equipped with. I'll loan you a Lowery Workstand and a magnifier light. There is thus no need to bring these heavy items with you to class. As I am on a bit of a mission to get everybody stitching on a proper slate frame (it is okay to do certain types of embroidery in hand or use a hoop, but goldwork embroidery is generally not suited), your embroidery kit contains a proper slate frame for you to take home. All future designs will fit this particular slate frame. My 'travelling' classroom can be set up almost everywhere. If you are interested in booking a workshop for your venue, please let me know. In this particular case, I had transferred the design onto the embroidery linen for the students. I've used the prick-and-pounce method with iron gall ink and a fine brush. These are methods that would have been known to medieval embroiderers. Dressing the slate frame was done in class. Students have access to videos in which both the transfer method and the dressing of the slate frame are shown. This means that you can fully concentrate on the stitching whilst in class and that there is minimal need for jotting things down. And these are the results after about 10 hours of tuition! I will make sure that you have stitched every technique during class (bar some minor very simple things one really only can do once most of the embroidery is finished). As I perfectly know that life is busy for most of us, students are usually unable to continue stitching when they get home from a workshop. That's why I provide full video instructions of all parts of the workshop.

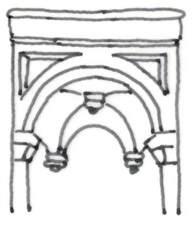

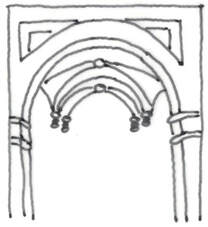

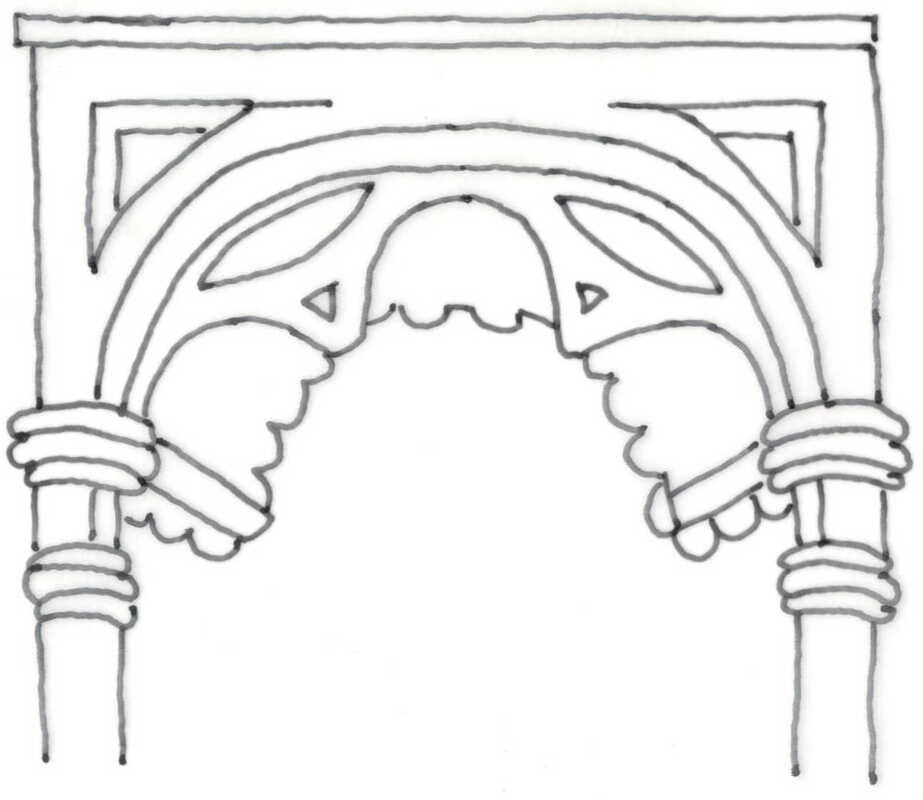

This year's goldwork embroidery workshop at Glentleiten was a great success! Visitors were able to watch the stitching and ask questions. I was able to give out my business card to those interested in attending a workshop in the future. Visitors remarked how much they appreciated to encounter 'life' in the museum building. A huge thank-you to the museum Glentleiten who do not charge me for using their building. The only money they make comes from the entrance fees of the students attending the workshop. That's a rare deal these days. I am looking forward to seeing 'my ladies' again next year. If you are interested in joining us, make sure you are subscribed to my newsletter! After I originally published my blog post on certain similarities between some orphreys held in Museum Catharijneconvent and the orphreys on the copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece, an interesting discussion developed with Andrejka of Štikarca needle at work (do visit the website for beautiful embroidery and an interesting blog!). Although Andrejka does not agree with my observations, she did mention a third set of orphreys with a similar architectural background. Reason enough to explore the topic further. And please do chime in with your observations and opinions as they are very much appreciated! To clarify why I think the backgrounds of all three sets of orphreys are related to each other, I have made line drawings of their canopies (this term was coined by Dr Beatrice Jansen in 1948; more on her work later). The squareness of the front of the canopy with the two open 'triangles' of the buttresses above the arch is the same in all three pieces. The actual vault differs a bit. In the pieces from the Museum Catharijneconvent and those from the collection of Sam Fogg, it is a rib vault typical for the Gothic period (either a single one or a double one). The orphreys on the cope of the Order of the Golden Fleece display a barrel vault. Although barrel vaults were known in antiquity, they were re-discovered in the Renaissance. Interestingly, the colour scheme for all three is the same: red/orange for the inside of the arch, triangles and columns and blue for the vaults. Strangely, the Sam Fogg catalogue does compare their orphreys with those of ABM t2107 and ABM t2165, but not with ABM t2114, ABM t2215 or BMH t622, although they are in the same museum and are much more identical to their own pieces. For me, the form of the canopy of the orphreys held by Museum Catharijneconvent, Sam Fogg and the copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece stand out from all the other 'Dutch' canopies out there. Interestingly, Dr Beatrice Jansen was also not able to assign these to one of her 'canopy groups'. She sees BMH t622 as a stand-alone design (she was clearly unaware of ABM t2114 and ABM t2115).

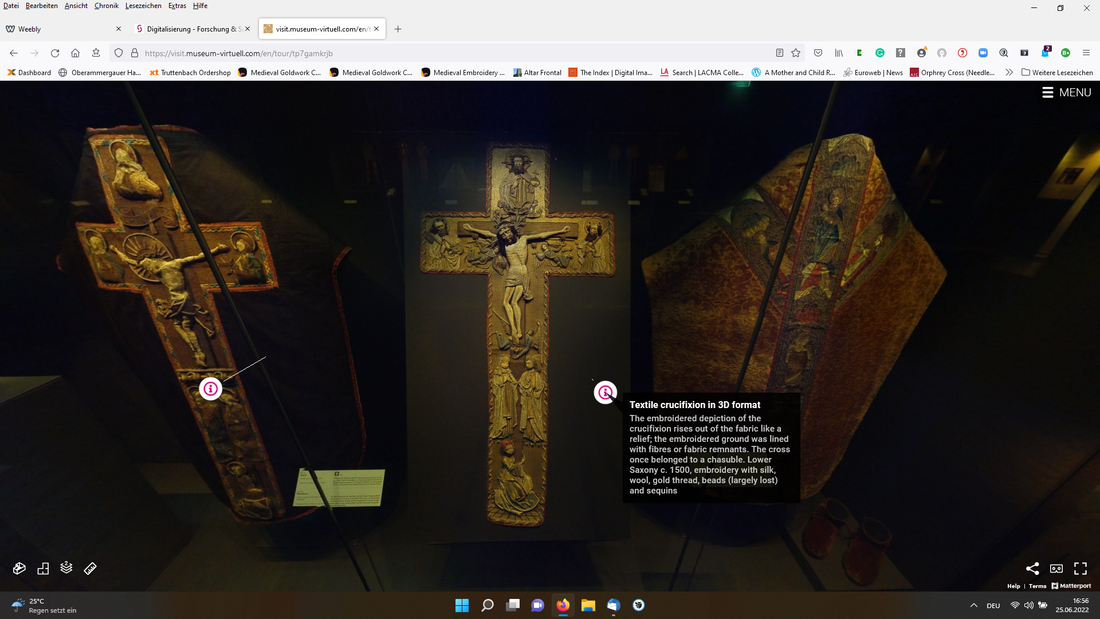

The origin of the ABM t2114 and ABM t2115 is given as Northern Netherlands and the date as AD 1490-1500. However, BMH t622 is seen as originating in the Southern Netherlands and dating to c. AD 1490. The vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece were made in the Southern Netherlands between AD 1425-1440. Sometimes the diaper patterns can help further pinpoint the likely place of origin. The diaper pattern seen in the orphreys from the Sam Fogg collection is one I had not seen before (it is a basket weave with four linked squares in the middle and all lines are worked double). ABM t2114 also sports an unusual chevron pattern behind Andrew the Apostle. Currently, there are only six other pieces in my database. Unfortunately, these pieces date from AD 1400-1599 and were made in the Netherlands, Germany, Spain and possibly England. The orphreys on the copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece do not sport diaper patterns. And then there is this strange practice of showing some figures turned away from the viewer. In ABM t2115 it is Phillip the Apostle. On the Sam Fogg orphreys, it is a male figure with a scimitar (Middle Eastern sword). Some figures on the copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece are also turned away from the viewer. The figures on the orphreys from Museum Catharijneconvent and those in the collection of Sam Fogg are stitched completely in a form of silk shading. Those on the copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece are stitched in or nue. Clearly, there is a big difference in quality between these three pieces. The copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece are the most elaborate and best-worked pieces. The pieces of the Museum Catharijneconvent differ a bit in quality. Some are very well made; others were clearly stitched by a less-experienced person. Nevertheless, they are all of better quality than those in the collection of Sam Fogg. My idea is, that the makers of the orphreys held at Museum Catharijneconvent and those in the collection of Sam Fogg might have been located in the same city in the Northern or Southern Netherlands at the end of the 15th-century. Maybe, one of them saw the copes of the Order of the Golden Fleece and took some of the design elements, adapted the embroidery style to suit his client's purses and created new orphreys. What do you think? Literature Garrett, R. & M. Reeves, 2018. Late Medieval and Renaissance textiles. Sam Fogg, London. Jansen, B.M., 1948. Laat Gotisch Borduurwerk in Nederland. L.J.C. Boucher, Den Haag. Leeflang, M., Schooten, K. van (Eds.), 2015. Middeleeuwse Borduurkunst uit de Nederlanden. WBOOKS, Zwolle. In a bit to compensate people for the high energy prices, Germany offers regional transport tickets for only nine Euros per month during June, July and August. Apparently to get commuters out of their cars and into public transport. Good luck to those of us living rurally. For example, my husband. He works in Ettal. That's only 18 km from where we live. He starts work at 9:30h. Public transport can either get him there at 7:20h or 9:50h. He ends work at 17:30h. Last travel option 17:05h. My husband would be perfectly willing to have a public transport commute of 45 minutes instead of the usual 20 by car. However, he is simply unable to take up the offer as there is no public transport available. On the upside: I use my ticket to do a bit of research travelling! Yes, it takes a long time to paste regional trains together to get from the South of Germany to the North, but it is practically free. Besides, there are only regional trains running when you go from the South to the East on many routes. Something that was never fixed since the wall came down. You also need to be flexible as the trains are very crowded and there is no guarantee that you can be transported. So, what did I visit? Three of the most important medieval and Renaissance textile collections in the world. We'll kick off with two of them: Domschatz Halbertstadt and St. Annen Museum Lübeck. My travels started off in Halberstadt. The cathedral treasury houses one of the most important cathedral treasures in Europe. It is probably also one of the museums with the largest permanent display of medieval textiles. Over 70 pieces, from luxurious patterned silks, to amazing goldwork embroidery to stunning whitework and huge tapestries, can be seen. There are only two major downsides: the level of lighting is so poor that you will have a hard time seeing the embroidery clearly. And secondly: you are not allowed to take pictures (which I doubt you can without flash anyway). Modern LED-lighting concepts for museums can allow for a better visitor experience but this costs money. Luckily, there is a beautiful publication (see literature list at the bottom of this post) which has beautiful colour pictures and detailed descriptions of about 60 pieces. It even contains many close-up pictures where you can literally see every stitch. There is also a full collection catalogue underway which will be published through the Abegg Stiftung. In my personal opinion, their publications are the gold standard when it comes to embroidered textiles. When you are interested in medieval embroidery, the Domschatz Museum should be on your 'to visit list'. You can easily spend several hours here. I'll recommend that you come prepared and have read the below-mentioned publication. This way you'll have so much more information as the museum captions are rather anecdotal. For those of you who cannot visit in person, the museum website has an excellent digital tour. Click on 'menu' at the top right and choose between DE or EN for language. Then click on the door opening. Depending on your internet connection and your device, be patient while the application loads. Click on 'floor selector' bottom left and choose 'floor 2'. The textile rooms are on either side of the main structure. Left for the whitework and the tapestries and right for the embroidered vestments. Enjoy! From Halberstadt, I travelled on to Lübeck in the North. That's almost 900 km from home :). The St Annen Museum is located in a former convent and also houses one of the most important textile church treasures in Europe. Due to the peculiarities of (recent) European history, Lübeck houses the treasury of St. Mary's church in Gdansk (formerly Danzig). For conservational reasons, only a tiny fraction is on display at a time (check the website to see which pieces). However, recently a complete collection catalogue was published (see literature list below). The texts are detailed, but could contain a bit more on the embroidery in most cases and not all pictures are as detailed as an embroiderer wishes. Nevertheless, it is a must-have addition on your shelves when you are into medieval (embroidered) textiles. My main reason for visiting the St Annen Museum now, was that the cope hood with a stumpwork version of St Georg and his pet was on display. This stunning piece of stumpwork embroidery was made around AD 1500 in Northern Germany. Sorry for those of you who think that stumpwork is an English invention. It is not. It was invented on the continent a good 100 to 150 years before 17th-century English stumpwork was made. Due to language barriers and not much appreciation on the side of art historians, these pieces have not gotten the scholarly attention they deserve. St George and his pet are pretty high on my recreation wish list :). Unfortunately, the construction of his head needs the help of a specialist wood cutter and a lot of trial-and-error. But this is definitely something I want to tackle in the future!

Literature Borkopp-Restle, B., 2019. Der Schatz der Marienkirche zu Danzig: Liturgische Gewänder und textile Objekte aus dem späten Mittelalter. Berner Forschungen zur Geschichte der textilen Künste Band 1. Didymos, Affalterbach. Meller, H., Mundt, I., Schmuhl, B.E.H. (Eds.), 2008. Der heilige Schatz im Dom zu Halberstadt. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg. The 30 hours of teaching have come to an end at the Alpine Experience. One more fantastic dinner tonight and then my husband and I will drive back after breakfast tomorrow morning. All students have done a fantastic job and I am very proud of their progress. Or nue is both a very simple technique and one of the hardest things you can do. You start off swimming a bit (and I will let all able-bodied persons swim a bit, but not drown ;)) but when it clicks with you, you will have learned a skill for life. Or nue is a very versatile embroidery technique and I can't wait to see my students incorporate it into future projects (but please finish Elisabeth first!) and encourage others to learn the technique too. By the way, the scientific part of this course has yielded the first results. All students used the same pricking and the resulting inked outlines lay within 0.3 mm length-wise and 0,1 mm width-wise. This shows that when a medieval pricking and a preserved embroidery (the underlying ink drawing rather) are out by several millimetres, they likely do not belong together.

Here are the results of a week of hard work: Today we had another full day of stitching at the Alpine Experience. The ladies were competing in a friendly race on who would be able to introduce the green silk first (Elisabeth has a red dress and a green mantle). Lots of laughter and bending of the rules :). We also had another visitor. After lunch, a beautiful red cat came walking in as though he totally owned the place. As it is quite impossible to finish all of Elisabeth during the 30 hours of tuition at the Alpine Experience, students will have access to a set of instruction videos. They also have the choice of working Elisabeth in the same shades of silk that I have used, or they can colour match using this lovely collection of Chinese flat silk. In a couple of weeks (months?), we will all meet on Zoom to check in on progress and discuss any questions which might have come up.

Today we had a full day of stitching at the Alpine Experience. Interspersed with fabulous food made by Mark and served by Nadine. And we had a couple of interesting visitors. Firstly, Harry the lizard. He seems to like sunbathing on Cathryn's trestles. We are pretty sure that he sleeps in the couch at night :). As the Alpine Experience is situated in a beautiful area, most of us like to take walks after class to stretch after a whole day of sitting and to let our eyes rest on the horizon. There is a particularly lovely short walk through the forest to the next hamlet. Plenty of wildflowers and butterflies included. And some gorgeous old buildings and cottage gardens to admire. Today, I picked up a mildly lost man from Guadeloupe. We stroke up a conversation in English (with a bit of my broken French) on our concepts of God. And it was really quite amazing! He also asked if he could see our embroidery as his mum used to embroider. As you know from a previous post, my ladies are not averse to a beautiful male :). This kind soul was very impressed and thanked us for the wonderful opportunity and then continued on his walk. Les Carroz is a truly magical place! Tomorrow, I'll show you Cathryn's version of Elisabeth; I took a picture of her piece at the wrong angle ...

|

Want to keep up with my embroidery adventures? Sign up for my weekly Newsletter to get notified of new blogs, courses and workshops!

Liked my blog? Please consider making a donation or becoming a Patron so that I can keep up the good work and my blog ad-free!

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Contact: info(at)jessicagrimm.com

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

Copyright Dr Jessica M. Grimm - Mandlweg 3, 82488 Ettal, Deutschland - +49(0)8822 2782219 (Monday, Tuesday, Friday & Saturday 9.00-17.00 CET)

Impressum - Legal Notice - Datenschutzerklärung - Privacy Policy - Webshop ABG - Widerrufsrecht - Disclaimer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed